Fig. 48.1

This patient got a diagnosis of “Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome” when she was 3. As she was told that this is an untreatable disease and because she was free of symptoms, she never had other examinations. A recently new complete study at the age of 20 revealed that she has no vascular anomalies except a cutaneous capillary malformation

Venous Malformations

VM can be divided, according to the Hamburg classification, in truncular (or truncal) forms (defects of the main veins, like aplasia, hypoplasia, stenosis, or dilatation – aneurysm) and extratruncular defects [2] (see Chap. 21).

Truncular Malformations

Abnormal dilated superficial veins, sometimes including the saphenous vein, are a common type of truncular VM in the lower limbs. It includes diffuse dilated veins and aneurysm of a single vein, like the saphenous vein or others. This anomaly is different from a varicose vein because it is the result of a congenital defect of the superficial veins and not an acquired venous insufficiency. Typical of the truncular superficial dysplastic veins is the early appearance (often in childhood) at an abnormal site (often on the lateral edge of the limb) and the frequent presence of nevus (Fig. 48.2). Duplex ultrasound examination should study the deep venous system to exclude anomalies, like aplasia or hypoplasia [1]. If the deep venous system is normal, the superficial dysplastic veins can be removed surgically. Foam sclerosis is an alternative treatment; however, these veins respond lesser than varicose veins to that treatment.

Fig. 48.2

Superficial abnormal veins with diffuse nevus

Congenital aneurysms of the main veins may appear in different vessels; the most frequently involved are the internal jugular vein, the portal vein, the vena saphena magna, the popliteal vein, the azygos vein, and the vena cava superior; pulmonary embolism has been reported in 6.1 % of cases [3–5]. Venous aneuryms of the lower limbs, like in the popliteal vein, is more likely the source of pulmonary embolism [6]. Surgical treatment with radical resection in vessels like the saphenous or jugular veins is recommended. In the main vessels, like the popliteal or femoral vein, tangential resection or venous graft implant is the best option [7] (Figs. 48.3, 48.4, and 48.5).

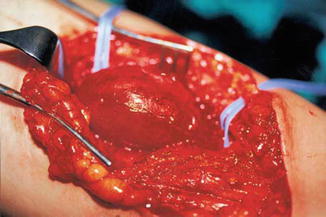

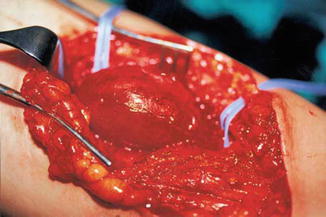

Fig. 48.3

Popliteal vein aneurysm

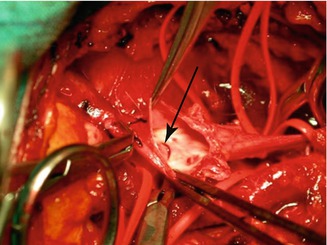

Fig. 48.4

Tangential clamping of the aneurysm by a Satinsky clamp

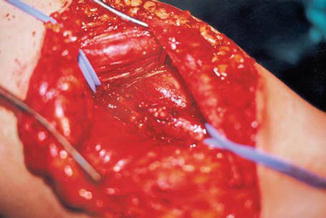

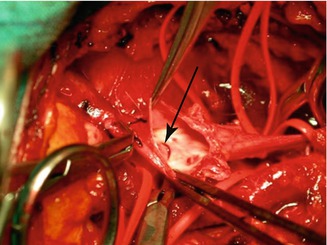

Fig. 48.5

After tangential resection and suture, the popliteal vein is of a normal caliber

The persistence of the marginal vein (MV), an abnormal, valveless vein sited on the lateral side of the lower limb, is not uncommon [8, 9] (Fig. 48.6). This vein is sometimes evident but in other cases may be not clearly visible because of subcutaneous fat: it can be recognized by palpation or, better, by duplex examination. This abnormal vessel may create swelling and a sense of heaviness due to the reflux. Limb length discrepancy by overgrowth (angio-osteo-hypertrophy) is sometimes possible because of slight AV communications around or toward the vein. In other, less frequent cases, limb hypotrophy (angio-osteo-hypotrophy) is possible with reduced growth of the limb. In these cases, often masses of pathologic dysplastic veins are associated to the marginal vein. Nevus is not always visible but often exists. The course and extension of the vein are variable: the classification of Weber distinguishes six types [10, 11] (Fig. 48.7). In some cases we found an abnormal lateral lymphatic vessel (the “marginal lymphatic”) sited parallel to the marginal vein; more details can be found in Chap. 27.

Fig. 48.6

A marginal vein of the right lower limb

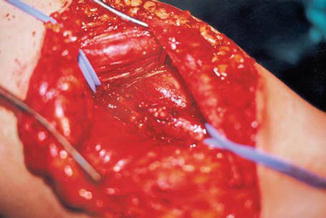

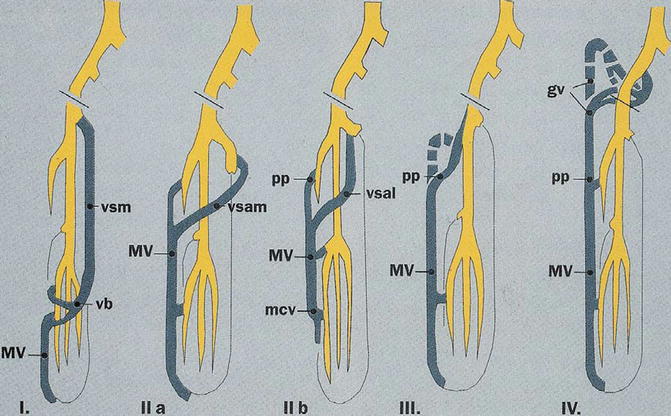

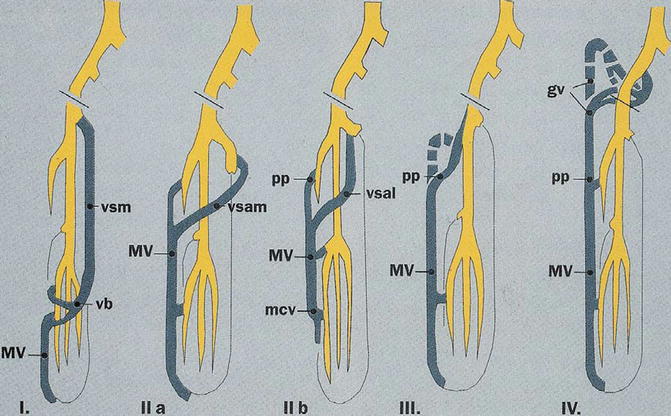

Fig. 48.7

Classification of marginal vein according to Weber: gv gluteal vein, mcv medial crural vein, MV marginal vein, pp deep perforants, vb anterior arched vein, vsam medial accessory saphenous vein, vsal lateral accessory saphenous vein, vsm main saphenous vein

If an MV with significant reflux is recognized, removal or occlusion is indicated [1, 8, 9]. Surgical resection is the most effective treatment. A correct mapping is required, preferably with duplex aid, in order to recognize site and size and locate perforators [12].

Surgical removal may be sometimes not easy in case of a large MV which may have fragile walls and many collaterals with risk of continuous bleeding, as surgery may be much longer than expected. Temporary ischemia by an Esmark band and a step-by-step planned treatment (avoiding one-step extensive surgery) are effective to reduce blood loss. Huge perforants should be recognized and carefully ligated as their persistence may be the cause of recurrence. Excellent results have been reported by surgical resection of MV [13] (Fig. 48.8).

Fig. 48.8

Surgical resection of a marginal vein. Operation revealed long lasting and with significant blood loss due to the fragility of the vein itself and to several, easy bleeding dysplastic veins. Complete resection of the MV was performed in three steps. By removal of the MV at the calf, a tourniquet was applied on the thigh to reduce blood loss. This adjunctive procedure is not always necessary for MV surgery and depends on the characteristics of the vein and of the existence or not of other dysplastic vessels that may bleed

Foam sclerosis is an alternative treatment which may be effective, especially in small-sized MV [14]. In large vessels with huge perforants, the treatment is less effective and may require several sessions. There exists also the risk of migration of the foam into the deep veins through large perforants.

Endovascular laser occlusion of the MV has been attempted by us with effective closure but with a very uncomfortable scar on the skin. MV is often very superficial and laser heating may affect the skin: saline solution injection between the vein and skin may prevent that complication. Recently this procedure has been reported successfully [15]. Radiofrequency occlusion may be an effective alternative.

In our opinion, endovascular occlusion and foam sclerosis are effective in small-sized MV; in vessels larger than 1–1.5 cm, surgery is the best treatment option.

The persistence of sciatic vein (PSV) is a rare venous truncular anomaly in which an abnormal draining vein, located intramuscularly in the thigh near the sciatic nerve, that normally disappears at birth, persists [16]. The vein drains blood from the popliteal area to the gluteal and internal iliac vein system. Sciatic vein is valveless and may create blood stasis in the thigh and in the calf and sometimes have more severe symptoms, like anorectal bleeding if the defect is coupled with AV pelvic malformations. An increased incidence of PSV was found in patients with complex venous malformations of the lower limb, like in the so-called Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome [17]. Diagnosis is not always easy: phlebography was the main diagnostic exam in the past [18]. Duplex ultrasound, phlebo-CT, and phlebo-MR are today excellent diagnostic methods to find out PSV. The treatment of PSV is required only if symptoms are severe. Resection of the distal connection of PSV with the popliteal or calf vein may be sufficient to eliminate distal symptoms; sometimes extended resection of the vein inside the thigh by a posterior approach has been performed. In a single case, the sural nerve was found inseparably in the wall of the vein, and, after surgical separation of the vein, a sural neuropathy persisted [18].

Hypoplasia of the deep veins, with more or less extended vein segments of a small caliber, is rarely described in literature, except by groups working intensively with CVM [19–21]. Hypoplasias are reported in the femoral, popliteal, and upper limb deep veins. These defects are commonly associated with cutaneous nevus and superficial dilated veins, acting as a collateral pathway. Sometimes, marginal vein may be also present. Limb overgrowth may also be visible. They may be the cause of venostasis and, sometimes, of distal ulcers. Complex cases may also include lymphatic defects of the main trunks which originate a clinical picture that may be denominated as the “Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome,” an old term which often is used improperly and creates confusion. This item is discussed in detail in Chap. 36.

Some authors were of the opinion that deep venous hypoplasia is always the result of an abnormal band compression which requires surgical removal [22]. However, other authors do not agree with this concept and believe that the so-called hypoplasia is the result of a defect in the development of the vessel and not an external compression, which has not been clearly demonstrated.

Belov reported that resection of dilated superficial veins may stimulate spontaneous dilation of the hypoplastic deep vein; he called this procedure “rerouting of venous flow” [23]. In extended hypoplasia, a step-by-step resection of the superficial veins is indicated, instead of a single procedure, in order to permit a progressive dilation of the stenotic vessels.

Aplasia of deep veins is well known, even if rare. Aplasia of the inferior vena cava is discussed in Chapter 46.

Aplasia of one common and/or external iliac veins is known, as also absence of the femoral and popliteal veins [24, 25] (Fig. 48.9); bilateral iliac vein aplasia is extremely rare [26], saphenous vein may also be missed [27]. Combinations of aplasias at different levels are possible. Aplasias of segments of the main veins of the upper limbs are much rarer.

Fig. 48.9

MR angiography demonstrating an aplasia of the left common and external iliac vein (red arrow). An evident suprapubic left-to-right spontaneous bypass is visible (black arrow)

Aplasia of the deep veins of the lower limb may compensate by collateral circulation through normal vessels, like the saphenous vein or profunda femoris, by dilated superficial, varicose-like veins or by persistence of abnormal veins like the marginal or sciatic vein. Different combinations are possible. There is no indication for the treatment of deep vein aplasia. Venous bypass techniques, even if theoretically possible, are not necessary as compensation is normally effective.

Truncular venous defects of the lower limbs may combine, like the marginal and/or sciatic vein and aplasia or hypoplasia of the deep veins. Correct differential diagnosis is crucial, as it conditions treatment [28].

Congenital avalvulia (congenital absence of valves in the deep veins) has been reported several times in the past but lesser in the last years [29, 30]. The common femoral, femoral, and popliteal veins may demonstrate extensive venous reflux due to the valve absence with calf and ankle swelling and pain (Fig. 48.10). The majority may tolerate the condition with elastic stockings, but in some patients symptoms may worsen till it is impossible to maintain a standing position for a longer time.

Fig. 48.10

Angio MR demonstrating avalvulia of the right femoral vein: notice the significant increase of diameter of the deep veins. The patient was treated in the past by ligation of the femoral vein at the connection to the common femoral vein. After a temporary improvement of symptoms, the patient worsens because of the connection of the deep femoral vein, also valveless, with the femoral vein distally (arrow)

In severe cases, treatment by valve reconstruction, like in postthrombotic insufficiency, is not applicable as valves are missing at all. The transplant of a valved vein segment from the axillary vein according to Taheri et al. [31] or a transposition of the femoral to the profunda femoris distally to a normal functioning valve, according to Kistner, is the best treatment option [32]. We treated three cases with the second technique with a good long-term result: all cases are functioning and symptoms improved significantly in two cases after a follow-up of 4 years (Figs. 48.11 and 48.12). The third case complained of a worsening of edema after treatment: examinations demonstrate perfect functioning of the transposition. Edema was the result of a lymphatic defect, probably by surgical injury in a case with an unknown primary congenital lymphatic defect (poor lymphatic drainage), that maintained a compensation until surgery.

Fig. 48.11

Opened deep femoral vein prior to anastomosis with a valveless femoral vein. The edge of the functioning valve is visible on the left (arrow). The common femoral vein is on the left; visible on the right are the bifurcations of the deep femoral vein

Fig. 48.12

Anastomosis of the femoral vein on the deep femoral vein distally to a functioning valve (arrow). The patient was free of symptoms at a follow-up of 4 years

Extratruncular Venous Defects

Areas of small abnormal veins infiltrating tissues can be found in every part of the limb. The intramuscular site is one of the most common location [33]. Every muscle can be affected; a limited, single muscle-type site can be observed, but extensive infiltration involving several muscles till an almost complete penetration of the whole musculature of a limb segment is also possible.

Extratruncular infiltrating dysplastic veins may also involve the skin, subcutis, bone, joints, and also nerves. Clinically, the limited intramuscular type may show no visible signs, while the more extended forms may manifest with bluish skin and visible masses which are easily compressible and empties spontaneously by limb elevation. Extratruncular venous dysplastic masses which are located around long bones may create bone hypotrophy by compression [34].

Duplex examination and MR are the best tests to find out the defect. However, an experienced examiner in vascular malformations will offer best results, especially in duplex examination, but also in MR [35].

Treatment by foam sclerosis has been attempted in these cases [36]. Foam sclerosis treatment in VM is discussed in Chap. 33.

Alcohol sclerosis by direct puncture of the dysplastic masses has been widely used in extratruncular VM [37, 38]. This technique is effective, allowing complete occlusion of the dysplastic area in many cases, even in extended infiltrating forms (Fig. 48.13). However, the technique should be well known and performed only by experienced physicians to avoid complications. It requires anesthesia (alcohol injection in vessels is very painful), which can be local or truncular, avoiding general anesthesia, if the procedure is limited to the limbs. A multiple-step procedure is often required. It is preferable in our experience to perform treatment every 2–3 months till almost complete occlusion of the malformed vessels, as recurrence is common if treatments happened at too long intervals.

Fig. 48.13

Diffuse infiltration of venous malformations of a whole limb, including muscles. The patient complains of pain crisis in some specific areas, due to episodic thrombosis. Treatment by percutaneous alcohol sessions centered on the pain areas improved significantly the conditions by eliminating episodic pain. In these cases complete occlusion of the diffuse infiltration is not possible, but local improvement may be well accepted

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree