Vascular Lesions

Vascular lesions of bone constitute a spectrum of pathologic entities. These range from congenital vascular malformations, i.e., errors of morphogenesis with nonproliferative capacity, which grow in parallel with the patient, such as angiomatosis, to benign neoplasms that may be present at birth, and highly malignant tumors that metastasize widely and have low survival rates (e.g., angiosarcoma) (28,101).

Recently, immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies have been conducted in attempts to discriminate between malformations and true tumors, the former being negative for WT1 [a transcription factor initially isolated from a hereditary Wilms tumor encoded by the so-called Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) gene (62)] and GLUT1 [an erythrocyte-type glucose transporter protein not present in normal vasculature and vascular malformations but found at sites of blood–tissue barriers and in vascular tumors (63,80)]. In addition, lymphatic lesions have been successfully identified by another monoclonal antibody, D2-40, that reacts with a formalin-resistant epitope on lymphatic endothelium (36,56). Boye et al. (12) were able to demonstrate clonality of cells isolated from proliferating (cellular) hemangiomas as well as alterations of their in vitro behavior, leading to the hypothesis that somatic mutations may be involved in their pathogenesis. Clonality of juvenile hemangiomas was also proved by Walter et al. (105) in 12 of 14 investigated cases. These authors also found somatic mutations in genes coding for the receptors (VEGFR2 and VEGFR3) of the vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs), which play an important role in angiogenesis and vascular formation (19).

Benign vascular tumors are of either endothelial or pericytic origin. The first group includes hemangiomas (2). Cystic angiomatosis, lymphangiomas, and lymphangiomatosis, although malformations, are also included here for reasons of differential diagnosis. The second group includes glomus tumor and its variants, glomangioma and glomangiomyoma. The malignant and locally aggressive varieties are quite uncommon and are mostly of endothelial (hemangioendothelioma and angiosarcoma) origin. The existence of hemangiopericytoma as a distinct tumor entity is currently a matter of debate (137).

Benign Lesions

Intraosseous Hemangioma

Hemangioma is a benign lesion composed of newly formed blood vessels, often discovered incidentally on radiographs performed for other reasons. It composes approximately 2% of all benign and 0.8% of benign and malignant lesions of the skeletal system (77). On the basis of their site of origin, hemangiomas in general are classified as intraosseous, intracortical, periosteal, intraarticular (synovial), intramuscular, subcutaneous, or cutaneous. Depending on size of the vessels predominating within the lesion, hemangioma is subclassified into capillary or cavernous types (25). Capillary hemangiomas are composed of small vessels that consist merely of a flat endothelium, surrounded only by a basal membrane. In bone they most commonly occur in the vertebral body (86). Cavernous hemangiomas are composed of dilated, blood-filled spaces lined by the same flat endothelium with a basal membrane. Osseous cavernous hemangiomas most commonly involve the calvaria (29).

The biological classification of vascular anomalies has recently gained renewed attention (72). Based on a system introduced by Mulliken and Glowacki (78), and redefined by Enjorlas and Mulliken in 1997 (28), this classification takes into consideration cellular turnover and histology, as well as natural history and physical findings. It clearly separates hemangiomas of infancy, with their early proliferative and later involutional stages, from vascular malformations, which are characterized as arterial, venous, capillary, lymphatic, or combined (24,72,78). The terms “venous hemangioma” (a lesion composed of thick-walled vessels that possess a muscle layer and frequently contains phleboliths) and “arteriovenous hemangioma” (characterized by abnormal communications between arteries and veins) are no longer in use. These lesions occur exceedingly rarely in bone, involve almost exclusively the soft tissues and at present time are considered as vascular malformations (28).

Clinical Presentation

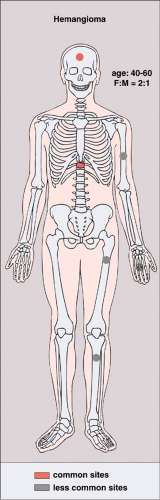

The incidence of intraosseous hemangiomas increases with age, and most patients present after their fourth decade. The majority of patients are asymptomatic and women are affected twice as often as men. The most common sites are vertebral bodies (particularly in the thoracic segment) and the skull. Hemangiomas of the long bones (e.g., femur, humerus) and short tubular bones are less often encountered (26,57,71) (Fig. 6-1). Calvarial hemangiomas most commonly affect the frontal and parietal regions, and account for 20% of all intraosseous hemangiomas (74). These lesions arise in the diploic space and cause expansion that often involves the outer table to a great extent (79). Vertebral hemangiomas are very common and are observed in 11% of autopsied cases (50). They account for 28% of all skeletal hemangiomas (74). In this location the lesion typically involves the vertebral body, although it may extend into the lamina and, rarely, into the spinous process. Multiple vertebrae are sometimes affected.

The majority of vertebral hemangiomas are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally. The pathologic fractures are rare (35). Symptoms occur when the affected vertebra expands in the direction of the spinal cord and causes compression (34,70,86). This neurologic complication is most commonly associated with lesions in the midthoracic spine (43,59,75). Another mechanism considered responsible for compression of the cord, although less frequently, is a fracture of the involved vertebral body and the formation of a soft tissue mass or hematoma (5,9).

The majority of vertebral hemangiomas are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally. The pathologic fractures are rare (35). Symptoms occur when the affected vertebra expands in the direction of the spinal cord and causes compression (34,70,86). This neurologic complication is most commonly associated with lesions in the midthoracic spine (43,59,75). Another mechanism considered responsible for compression of the cord, although less frequently, is a fracture of the involved vertebral body and the formation of a soft tissue mass or hematoma (5,9).

Imaging

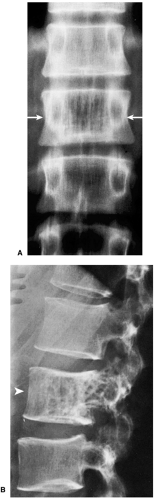

On radiography, an osseous hemangioma in a long or short tubular bone is characterized by coarse striations or by multifocal lytic areas (60,93) (Fig. 6-2). Periosteal and cortical hemangiomas occur most commonly in the anterior tibial diaphysis. These lesions present as lytic, cortical erosions, occasionally accompanied by a periosteal reaction. In the vertebral body, hemangioma is characterized either by vertical striations or by multiloculated lytic foci (108). These appearances are referred to as a corduroy cloth pattern (Fig. 6-3A) or honeycomb pattern (Fig. 6-3B), respectively, and are considered virtually pathognomonic for this lesion (60). A calvarial hemangioma commonly appears as a lytic lesion that exhibits a radiating configuration of

thickened trabeculae, frequently arranged in a spoke-wheel or web-like pattern (79).

thickened trabeculae, frequently arranged in a spoke-wheel or web-like pattern (79).

On computed tomography (CT) scan, vertebral hemangioma characteristically exhibits a pattern of multiple dots (often referred to as the “polka-dot” appearance), representing a cross-section of reinforced trabeculae (Fig. 6-4).

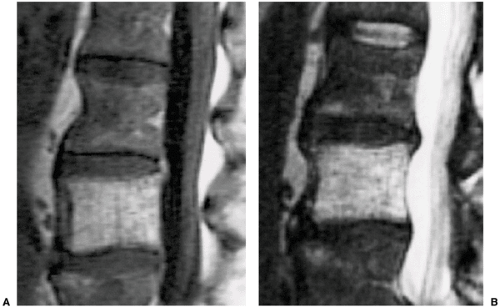

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), T1- and T2-weighted images usually reveal areas of a high-intensity signal that correspond to the vascular components, adipocytes, and interstitial edema (7,48,89,102) (Fig. 6-5). Areas of trabecular thickening exhibit a low signal intensity regardless of the pulse sequence used (79). Both CT and MRI obtained after intravenous administration of contrast material demonstrate a lesion enhancement (16,79,97,110).

On scintigraphy, the appearance of osseous hemangiomas ranges from photopenia (37,68) to a moderate increase in the uptake of radiopharmaceutical tracer (54,76,83). A recent study of single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging of vertebral hemangiomas and their correlation with MRI showed that in most cases hemangiomas exhibited normal uptake on planar images. SPECT images were also normal, particularly if the lesions were less than 3 cm in diameter. This study also showed a disparity between SPECT images and MRI: there was no correlation between MRI signal intensity changes and patterns of uptake on bone imaging (47). Arteriography of the hemangioma is rarely indicated (64).

Histopathology

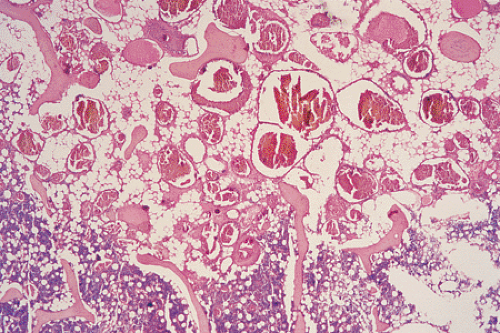

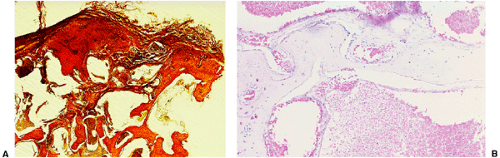

On histologic examination, most hemangiomas consist of simple channels formed by an endothelium-lined basal membrane, morphologically identical with normal capillaries (Fig. 6-6). The lining endothelial cells are small, flat, uniform, and inconspicuous (50). Mitotic figures are rarely seen (21). Some or all of the vascular channels may be enlarged and may have a sinusoidal appearance, in which case the lesion is

referred to as cavernous type (Fig. 6-7), which incidentally is the most common, particularly in the calvaria (31). These lesions are composed of multiple large, thin-walled, dilated, blood-filled vascular spaces lined by endothelial cells (50). Endothelial cells of hemangiomas are consistently positive for CD31, CD34, and factor VIII–related antigen. It has recently been shown that the Fli-1 protein, a transcription factor involved not only in cell proliferation and tumorigenesis, e.g., in Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) and lymphoma but also in formation of endothelial cells, including lymphatic endothelium, is expressed in the nucleus of normal endothelia and in endothelium-derived benign and malignant tumors (32,33). The hemangiomatous tissue often spreads between the preexisting bone trabeculae without distorting the original bone pattern (77).

referred to as cavernous type (Fig. 6-7), which incidentally is the most common, particularly in the calvaria (31). These lesions are composed of multiple large, thin-walled, dilated, blood-filled vascular spaces lined by endothelial cells (50). Endothelial cells of hemangiomas are consistently positive for CD31, CD34, and factor VIII–related antigen. It has recently been shown that the Fli-1 protein, a transcription factor involved not only in cell proliferation and tumorigenesis, e.g., in Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) and lymphoma but also in formation of endothelial cells, including lymphatic endothelium, is expressed in the nucleus of normal endothelia and in endothelium-derived benign and malignant tumors (32,33). The hemangiomatous tissue often spreads between the preexisting bone trabeculae without distorting the original bone pattern (77).

The designation epithelioid hemangioma is used for vascular lesions that, unlike epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, are often arranged in a lobular fashion (66,98,99,107). According to O’Connell et al. (81,162), more than 50% of neoplastic vessels should be lined by epithelioid endothelial cells to establish the diagnosis. Well-formed vessels with open lumina contain enlarged eosinophilic endothelial cells, sometimes protruding into the lumen, with vesicular nuclei and occasionally with prominent nucleoli. However, overt nuclear atypia is absent. Typical mitoses can be detected, and cytoplasmic vacuoles may be seen. The stroma often contains an inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and extravasated erythrocytes, but myxoid change or hyalinization is not present. However, the existence of an epithelioid hemangioma in bone similar to its soft tissue counterpart [which is also designated as angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia or histiocytic hemangioma and which is regarded by some authors as being reactive (106)] has been questioned by others (25,30).

Differential Diagnosis

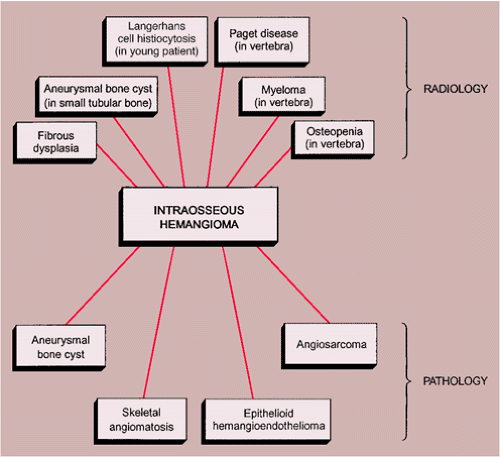

Radiology

Solitary hemangioma in a small tubular bone, such as a metacarpal or metatarsal, may exhibit an expansive appearance, thus mimicking an aneurysmal bone cyst (20). In a long tubular bone, particularly when the lesion is predominantly radiolucent, a focus of fibrous dysplasia may be the consideration.

In a vertebra, the differential possibilities include Paget disease, myeloma (plasmacytoma), and metastasis, and in a younger patient hemangioma may mimic a Langerhans cell histiocytosis. In patients with a significant degree of osteopenia, the vertebrae sometimes exhibit vertical linear streaks, similar to the appearance of vertebral hemangioma (Fig. 6-8). In Paget disease, the vertebral body, unlike in hemangioma, is frequently enlarged,

particularly dorsally, and the vertebral endplates are either indistinct or markedly sclerotic (“picture frame” appearance) (Fig. 6-9). If vertical striations are present, they are not so neatly arranged as in hemangioma (77). Myeloma and metastasis may exhibit lytic changes of the vertebral body, but there is no evidence of vertical striation. Conversely, hemangioma may present as a purely lytic lesion (Fig. 6-10). Langerhans cell histiocytosis usually presents as a collapsed vertebra (vertebra plana) (see Fig. 5-4), whereas hemangiomas of the vertebra exhibit pathologic fractures only in exceptional cases.

particularly dorsally, and the vertebral endplates are either indistinct or markedly sclerotic (“picture frame” appearance) (Fig. 6-9). If vertical striations are present, they are not so neatly arranged as in hemangioma (77). Myeloma and metastasis may exhibit lytic changes of the vertebral body, but there is no evidence of vertical striation. Conversely, hemangioma may present as a purely lytic lesion (Fig. 6-10). Langerhans cell histiocytosis usually presents as a collapsed vertebra (vertebra plana) (see Fig. 5-4), whereas hemangiomas of the vertebra exhibit pathologic fractures only in exceptional cases.

Pathology

On microscopic examination, intraosseous hemangioma cannot be distinguished from skeletal angiomatosis (58). Differentiation is therefore based on the extensive nature of the latter. Moreover, the presence of GLUT1 and/or WT1 immunoreactivity militates against a vascular malformation. The differential diagnosis from epithelioid hemangioma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and angiosarcoma should not be too difficult because flat, normal-appearing endothelial cells usually line the vascular spaces of hemangioma (162).

Epithelioid hemangioma must be differentiated from epithelioid hemangioendothelioma because of the different treatment modalities required (curettage or local excision vs. wide resection, eventually followed by chemotherapy). Epithelioid hemangioma consists of well-formed vessels, grows in a lobulated fashion, and contains inflammatory cells, including eosinophilic granulocytes and a nonhyalinized stroma. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma presents with a peculiar myxoid- to chondroid-appearing stroma and an infiltrative growth pattern of moderate atypical cells growing in strands or nests rather than forming vascular channels.

Figure 6-9 Paget disease. Vertebral body of L2 is enlarged, and the vertebral endplates are thickened, creating a “picture frame” appearance. |

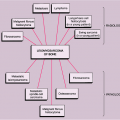

The radiologic and pathologic differential diagnosis of intraosseous hemangioma is depicted in Figure 6-11.

Synovial Hemangioma

Synovial hemangioma is a rare benign lesion of the synovium that most commonly affects the knee articulation. This entity is discussed in Chapter 9.

Cystic Angiomatosis

Angiomatosis is defined as a diffuse involvement of bones by hemangiomatous lesions (14,29,40,41,46,61,73,82), although some investigators also include cases of lymphangiomatosis (29,31,86). According to Enjolras and Mulliken (28), this lesion is a vascular malformation that, owing to its basic structural components, can be subclassified as either capillary, lymphatic, venous, arterial (rarely), or combined. In addition, further separation into slow-flow or fast-flow types appears to be clinically useful (44). The radiographic presentation of angiomatosis is that of lytic lesions, often with a honeycomb or lattice work (“hole-within-hole”) appearance

(13). When bone is extensively involved, the term cystic angiomatosis is applied (65,85). Some other terms used for this condition include diffuse skeletal hemangiomatosis (75,104), cystic lymphangiectasia (49), and hamartous hemolymphangiomatosis (91). This is a rare bone disorder characterized by diffuse cystic lesions of bone, frequently (60% to 70% of cases) associated with visceral involvement (52). Schajowicz (90) postulated that diffuse hemangiomatosis should be distinguished from cystic angiomatosis because of their different radiologic and macroscopic aspects. On histologic examination, cystic angiomatosis is characterized by cavernous angiomatous spaces, indistinguishable from benign hemangioma of bone.

(13). When bone is extensively involved, the term cystic angiomatosis is applied (65,85). Some other terms used for this condition include diffuse skeletal hemangiomatosis (75,104), cystic lymphangiectasia (49), and hamartous hemolymphangiomatosis (91). This is a rare bone disorder characterized by diffuse cystic lesions of bone, frequently (60% to 70% of cases) associated with visceral involvement (52). Schajowicz (90) postulated that diffuse hemangiomatosis should be distinguished from cystic angiomatosis because of their different radiologic and macroscopic aspects. On histologic examination, cystic angiomatosis is characterized by cavernous angiomatous spaces, indistinguishable from benign hemangioma of bone.

Figure 6-10 Vertebral hemangioma. Lateral tomography shows a purely lytic hemangioma of the posterior part of vertebral body T6 (arrows). This presentation may be mistaken for metastasis or myeloma. |

Another condition that must be distinguished is so-called Gorham disease of bone (18,39), also known by the names massive osteolysis (100), disappearing bone disease, and phantom bone disease (18,38). This condition is characterized by progressive, localized bone resorption (53), probably caused by multiple or diffuse cavernous hemangiomas or lymphangiomas of bone or by a combination of both (90). The radiographic presentation of Gorham disease consists of radiolucent areas in the cancellous bone or concentric destruction of the cortex, giving rise to a sucked-candy appearance (31). Eventually, the entire medullary cavity and the cortex are destroyed (4,103,111). On histologic examination, a marked increase is observed in intraosseous capillaries, which form an anastomosing network of endothelium-lined channels that are usually filled with erythrocytes or serum (90). Although some investigators claim that there is no evidence of osteoclasts in areas of bone resorption (38), recent studies suggest that osteoclastic activity plays a role in pathogenesis of Gorham disease (94).

Clinical Presentation

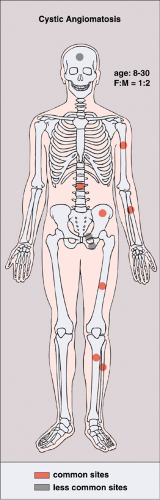

Patients with cystic angiomatosis usually present in the first three decades (79). There is 2:1 male-to-female predominance. The bones affected are most often those of the axial skeleton, as well as the femur, humerus, tibia, radius, and fibula (20,29,82) (Fig. 6-12). The bone- related symptoms are usually secondary to pathologic fractures through the cystic lesions. Most of the symptoms, however, are related to visceral involvement.

Imaging

On radiography, the osseous lesions are usually osteolytic (Fig. 6-13), occasionally with a honeycomb appearance (Fig. 6-14). They are well defined and surrounded by a rim of sclerosis, and they vary in size (15,67) (Fig. 6-15). Although medullary involvement predominates, cortical invasion, osseous expansion, and periosteal reaction can occur (20). Rarely, sclerotic lesions may be present, and in these instances the condition may mimic osteoblastic metastases (51). On MRI the lesions usually show an intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images, and T2-weighted images with fat saturation show a mixture of high, intermediate, and low signal intensities (8).

Figure 6-12 Cystic angiomatosis: skeletal sites of predilection, peak age range, and male-to-female ratio. |

Histopathology

Whether cystic angiomatosis is truly of blood vessel origin or of lymphatic derivation, or even represents a mixture of the two, is difficult to decide in a given case without IHC (50). On gross examination, the lesions of cystic angiomatosis resemble simple bone cysts (20). They consist of large cavities lined by a dull yellowish- gray membrane. Multiple communicating cysts, separated by thickened trabeculae of mature lamellar bone but without osteoblastic rimming (107), may also be present, producing a honeycomb appearance (87). In some cases osteoid and immature woven bone formation with rimming of active osteoblasts was reported (51). Histologically, the lesions are indistinguishable from those observed in capillary or cavernous hemangiomas (20). They contain multiple dilated, thin-walled vascular channels lined by flat endothelial cells (107).

Differential Diagnosis

Radiology

The predominant differential diagnosis must include polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, enchondromatosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, brown tumors of hyperparathyroidism, and pseudotumors of hemophilia (95). In older patients, although the diagnosis of metastatic disease (42) and multiple myeloma must be considered, these conditions usually can be easily distinguished on the basis of both radiologic and clinical examinations. The osteosclerotic variant of cystic angiomatosis must be differentiated from osteoblastic metastases (1,17,51), sclerosing variant of myeloma (104), lymphoma, and mastocytosis (6). Careful interpretation of the radiographs may reveal the presence of mixed sclerotic and lytic lesions in cystic angiomatosis, a feature that is helpful in excluding some of the mentioned entities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree