(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

Variations in the procedure of routine hemipelvectomy (i.e., posterior flap hemipelvectomy) are often required because of the location and extent of the tumor or because prior treatment such as radiation may have obliterated the normal tissue planes. One of the situations commonly encountered is a high location of the tumor in the iliac fossa, well above the level of the inguinal ligament. Many of these tumors can be effectively removed with the use of the abdominoinguinal incision and do not require amputation.

In the case of an extensive tumor requiring an amputation and infiltrating the lower abdominal wall, a considerable portion of the lower abdominal wall must be removed en bloc with the tumor. The resultant large defect, if anticipated, can be taken care of by the construction of a particularly long posterior flap, created by making the posterior part of the incision about 10 cm below the gluteal crease, in order to have adequate length. Usually this long posterior flap will survive if the gluteus maximus is left attached to the flap, particularly if the blood supply or part of the blood supply provided through the inferior gluteal vessels can be preserved. At least the blood supply provided through the sacral origin of this muscle should be preserved, as will be the case if the sacral origin of the muscle is not detached from this bone.

For a high resection of the anterior abdominal wall to the umbilicus, a long posterior flap may not suffice. In this situation, one can place polypropylene mesh on the defect, provided that direct contact between the mesh and bowel loops can be prevented by having peritoneum or elongated omentum under the mesh. In this case, the tissues underlying the polypropylene mesh are allowed to develop an ingrowth through the pores of the mesh. After a few weeks of outpatient wound care, the patient may have a split-thickness skin graft applied to the area of granulation tissue. Some muscles (e.g., the contralateral rectus abdominis, based on the inferior epigastric vessels) have also been used to cover a defect in the posterior flap closure.

Some authors have argued that by opening the peritoneal cavity through a lower midline incision added to the routine incision of posterior flap hemipelvectomy, early ligation of the iliac vessels can be secured, minimizing blood loss during the hemipelvectomy. This particular rationale for the procedure is not a strong one, because the exposure of the iliac vessels through the extraperitoneal approach afforded by the routine hemipelvectomy incision allows an early ligation and division of the iliac vessels at the appropriate level. Occasionally, however, a combination of the lower midline incision (from just above the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis) with the routine incision for posterior flap hemipelvectomy may be required. It can be very useful in cases of tumor in the area of the iliac fossa, which is not amenable to resection through an abdominoinguinal incision and which extends all the way to the lumbar spine. In this case, the lower oblique incision above the inguinal ligament and along the entire length of the iliac crest posterolaterally does not suffice to expose the upper medial extent of the tumor near the lumbar spine and to allow dissection around it.

If the tumor extensively involves the skin up to the inguinal ligament anteriorly and up to the mid buttock posteriorly but does not involve the tissues deep to the investing fascia, one can circumscribe the tumor extension at the level of the skin and subcutaneous tissue proximally (such as in the case of in-transit lesions from malignant melanoma that are not amenable to hyperthermic perfusion) and carry the dissection posteriorly on the surface of the gluteus maximus to the inferior edge of this muscle. This procedure preserves the muscle’s lower portion and allows it to be sutured to the anterior edge of the abdominal fasciae for closure of the defect, with application of a skin graft on the exposed part of gluteus maximus.

In patients with prior radiation to the iliac region who require a hemipelvectomy with an anterior or posterior flap, the peritoneum cannot be dissected off the iliac fossa or the lower abdominal wall. The procedure therefore becomes a transperitoneal one, but otherwise it proceeds along the same lines as the extraperitoneal procedure. At the end of the operation, the small bowel loops come to rest against the flap, but this situation is not a problem if one has taken care that the viability of the flap is secure and it has a smooth internal surface without any deep “pockets” in which bowel loops may become trapped.

Anterior Flap Hemipelvectomy

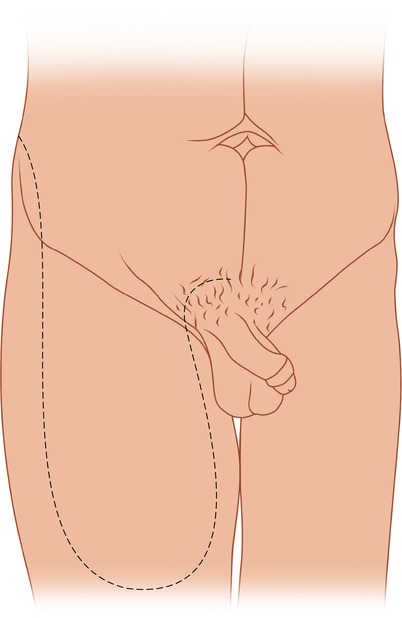

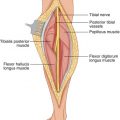

Anterior flap hemipelvectomy is the main variation of the procedure. It is indicated for tumors in the buttock that also involve the innominate bone, so that a lesser procedure is not possible. The incision extends from the posterior superior iliac spine along the iliac crest to the anterior superior iliac spine and then continues vertically downward to the distal thigh, cutting through the subcutaneous fat and the fascia lata. It then curves a few centimeters above the patella and ascends on the medial side of the thigh, along the approximate position of the anterior border of the gracilis muscle, continuing to the pubic tubercle (Fig. 55.1). The posterior incision is carried out well above the level of the tumor in the buttock (Fig. 55.2) and is made to join the anterior part of the incision laterally at the anterior superior iliac spine or more posteriorly at the iliac crest. On its medial side, the incision is carried from the posteromedial buttock along the genitocrural crease to the pubic tubercle and then transversely to the pubic symphysis (Fig. 55.3). The anterior flap is centered over the rectus femoris and the course of the superficial femoral vessels. The lower transverse portion of the incision is carried through the fascia lata about 10-cm above the patella, exposing the rectus femoris, which is divided. The dissection then continues on the undersurface of the rectus femoris in a cephalad direction. The branches of the lateral femoral circumflex artery arising from the profunda are identified, and the plane is kept deep to these branches so that the branches to the rectus femoris and skin remain intact. On the medial side of the inferior edge of the anterior flap, as the fascia is incised, the sartorius muscle is exposed and divided. Behind the divided sartorius muscle, the superficial femoral vessels are also ligated and divided, and then a plane is maintained deep to the superficial femoral vessels and preferably deep to the plane of the rectus femoris and its blood supply (Fig. 55.4). As one proceeds proximally, the profunda femoris vessels are encountered, ligated, and divided deep to the origin of the lateral femoral circumflex artery and vein. The medial femoral circumflex branches of the profunda vessels are ligated and divided close to their entry in the space between the pectineus and the psoas. The flap is freed laterally by dividing the origin of the rectus femoris off the anterior inferior iliac spine and that of the sartorius off the anterior superior iliac spine. Then the deep circumflex iliac vessels are ligated and divided close to their origin from the terminal part of the external iliac vessels; these vessels, enclosed in a fascial sheath, course laterally toward the iliac crest behind the inguinal ligament. The dissection continues on the surface of the iliopsoas muscle to the level of the sacroiliac joint. Medially, the internal iliac vessels are encountered. They may be preserved unless there is tumor adjacent to them or they hinder exposure, such as for a high division of the iliac bone. In this case they are ligated and divided close to their origin from the common iliac vessels. The femoral nerve is divided above the level of the iliac crest as it emerges between the fibers of the psoas muscle to occupy a position between the psoas and the iliacus (Fig. 55.5). The quadratus lumborum muscle is divided to expose the iliac crest all the way to the sacroiliac joint. The short posterior flap is elevated off the fascia covering the proximal portions of the gluteus maximus and medius muscles until the posterior portion of the iliac crest and the side of the sacrum are exposed. The sacroiliac joint is exposed posteriorly, medially, and anteriorly, and then the greater sciatic notch is dissected with blunt finger dissection, avoiding any bleeding from the gluteal branches, particularly the veins which are more prone to disruption and bleeding. Once the sacroiliac joint has been exposed at the greater sciatic notch, it is also exposed proximally and divided with an osteotome (Fig. 55.6). Medially, the pubic symphysis is exposed and a Gigli saw is passed around it, which helps to divide this structure. The extremity is now retracted caudally and laterally. The levator ani muscle is divided, along with the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments posteriorly, allowing the specimen to be removed (Fig. 55.7). The large defect in the buttock comprises a defect not only in the musculature but also in the skin. This defect will be covered with the large anterior flap that has been developed, which will reach a high location posteriorly and will retain viability because of its excellent blood supply (Fig. 55.8).