Urinary Tract Cytopathology

Christopher J. VandenBussche

Syed Z. Ali

George Papanicolaou demonstrated the usefulness of examining urinary sediment smears to diagnose urinary tract cancers in 1945; today, urinary tract (urinary tract) specimens have become one of the most common cytopathology laboratory specimens after the Pap test (1,2). The original purpose of urinary tract cytopathology, the detection of urothelial cancer, remains its mainstay.

The 2013 International Congress of Cytology meeting in Paris, France, established an international working group aimed at standardizing the terminology used in reporting urinary tract specimens and examining the practice patterns among different institutions. This effort was established due to the nonuniform practice of urinary tract cytopathology among cytopathologists, a lack of confidence among some pathologists when examining urinary tract specimens, and questions surrounding the clinical utility of urinary tract cytopathology. These factors both resulted in and were perpetuated by relatively high rates of indeterminate diagnoses at many institutions, sometimes approaching one third of all urinary tract specimens (3).

The result from the international working group was the Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology (TPS), which was finalized at the end of 2015 and accepted by both the American Society of Cytopathology and International Academy of Cytology. In short, TPS identifies the high positive predictive value (PPV) for high-grade urothelial carcinoma (HGUC) as the primary strength of urinary tract cytopathology. This strength is emphasized by the TPS, as it focuses almost exclusively on the use of urinary tract cytopathology to identify features of HGUC and stratify urinary tract specimens according to risk for HGUC and urothelial carcinoma in situ (CIS).

BENEFITS AND DRAWBACKS OF URINARY TRACT CYTOPATHOLOGY

Voided urine specimens can be produced conveniently, cheaply, and noninvasively. Processing of these specimens is also relatively inexpensive and quick. Because specimens are concentrated during processing, relatively little time is required for their microscopic examination. Turnaround time can be same day if necessary. Because urine is produced from the kidneys in the upper urinary tract, a voided urine specimen represents a sampling

of a patient’s entire urinary tract. When samples are well preserved, the cytomorphologic features of HGUC are specific and a malignant diagnosis has a PPV that approaches 100% (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

of a patient’s entire urinary tract. When samples are well preserved, the cytomorphologic features of HGUC are specific and a malignant diagnosis has a PPV that approaches 100% (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

The primary drawback to voided urine specimens is their relatively low sensitivity (50% to 85%) for HGUC (10, 11) and even much lower sensitivity for low-grade urothelial neoplasms (10% to 43.6%) (10, 11). Diagnosis by urinary tract cytopathology requires neoplastic cells to be present in the urine specimen, but patients with dilute urine or a low tumor burden may have few-to-no malignant cells in a given sample. Therefore, the use of serial samples over time is recommended when a patient is being followed using voided urine specimens alone. Even large low-grade neoplasms shed tumor cells less frequently than high-grade lesions, and thus, urinary tract cytopathology has poor specificity and sensitivity for low-grade lesions. Because voided urine specimens represent the entire urinary tract, one cannot localize a lesion using voided urine specimens alone. Therefore, a malignant voided urine specimen needs to be correlated with cystoscopy, pyelogram, and/or radiographic results; in these instances, follow-up with location-specific urine specimens obtained through cystoscopy is often useful. Positive results may be especially difficult to clinically correlate in the case of flat (CIS) or small tumors, tumors in obscured locations, and tumors that mimic pathophysiologic and/or reactive processes such as stenosis or infection (12, 13). While this phenomenon of an “anticipatory positive” result may seem beneficial, early positive results can cause frustration for the urologist, who cannot treat a tumor until it is localized.

Urinary tract specimens obtained by instrumentation can help localize a neoplasm by washing (barbotage) or brushing a specific location of the urinary tract. These specimens can sometimes be taken directly from an abnormal area identified during cystoscopy and correlated with a concurrent tissue biopsy. Because the washing process disrupts urothelial cells, the cells obtained are generally better preserved and more numerous than those found in a voided urine specimen. Furthermore, instrumented specimens can improve the sensitivity for detecting HGUC in the upper tract when compared to voided urine specimens (14). However, washing and brushing techniques also exert physical forces on the cells, which can result in cytomorphological artifacts. Additionally, normal urothelial lining can also be removed, resulting in very cellular specimens that, even if entirely benign, may give the impression of a neoplastic process. Compared to voided urine specimens, instrumented specimens are more expensive to obtain, require a more invasive procedure, and are more inconvenient to the patient.

HIGH-GRADE UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA

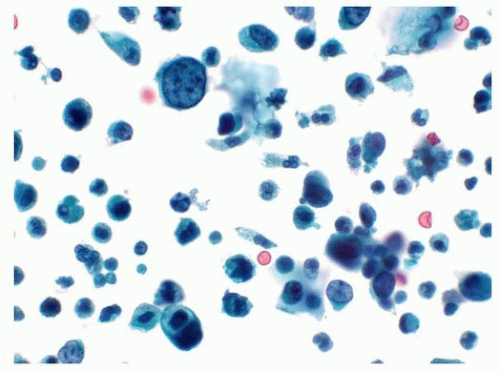

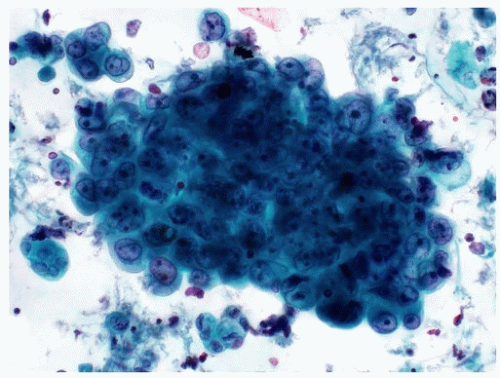

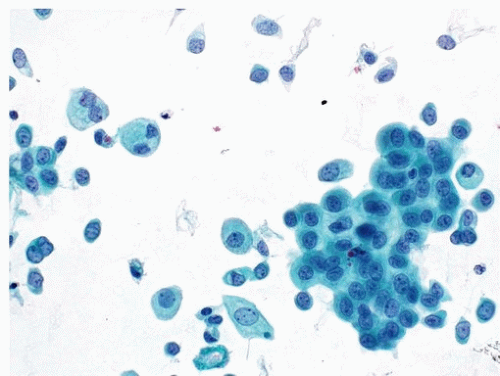

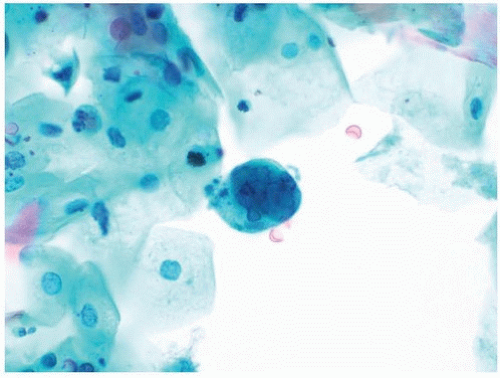

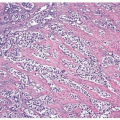

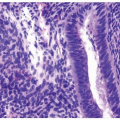

A cytological diagnosis of HGUC correlates with a histological diagnosis of either noninvasive high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma or invasive HGUC. Because the primary goal of TPS is to identify HGUC, it is most important to be familiar with the cytomorphological features of HGUC (Figs. 14.1, 14.2) (1, 15, 16). HGUC cells in the urine are pleomorphic and

exist on a morphological spectrum, which at one end could be confused with benign, reactive urothelial cells (17). Furthermore, most specimens contain degenerative changes that can alter the cytomorphologically critical features. Therefore, a urinary tract specimen may be very cellular and contain abundant tumor cells, only a small fraction of which may contain all the diagnostic criteria for HGUC:

exist on a morphological spectrum, which at one end could be confused with benign, reactive urothelial cells (17). Furthermore, most specimens contain degenerative changes that can alter the cytomorphologically critical features. Therefore, a urinary tract specimen may be very cellular and contain abundant tumor cells, only a small fraction of which may contain all the diagnostic criteria for HGUC:

1. High N/C ratio. Malignant cells should have an N/C ratio of 0.7 or greater, meaning that the nucleus occupies at least 70% of the cytoplasm. While HGUC cells tend to have larger nuclei than reactive or low-grade urothelial neoplasia (LGUN) cells, the N/C ratio is a more specific feature because increase in cell size lags that of nuclear size increase.

2. Moderate to severe hyperchromasia. Practically, the amount of hyperchromasia should be sufficient to clearly distinguish the amount of chromasia from that of bystander benign urothelial cells.

3. Markedly irregular nuclear borders.

4. Coarse, clumpy chromatin.

All of the above diagnostic criteria must be present in at least five well-preserved urothelial cells to merit a diagnosis of HGUC. Because an HGUC diagnosis from upper tract specimens can potentially result in a nephrectomy, it is recommended that at least 10 well-preserved urothelial cells be required for an HGUC diagnosis in the upper tract specimens.

While the quantity of malignant cells, presence of tumor diathesis, and level of atypia are all likely associated with a patient’s tumor burden, there is no strong evidence to suggest that urinary tract cytopathology can reliably distinguish between invasive and noninvasive HGUC and no such commentary should be made (4).

Carcinoma In Situ

Urinary tract cytopathology has tremendous utility in the diagnosis of CIS that can be difficult to identify and biopsy on cystoscopy. While some studies exist purporting to identify cytomorphological features distinguishing CIS from high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma, the criteria used by TPS do not distinguish between HGUC and CIS (18). Therefore, a diagnosis of HGUC on urinary tract cytology includes both high-grade papillary lesions and CIS.

Variants of HGUC

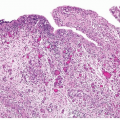

Many histologic variants of HGUC are rare and do not have well-established features on urinary tract cytopathology, although some case reports exist purporting to associate certain features with particular variants (19). Due to the lack of evidence regarding the cytologic correlations of these histologic variants, in most instances, it is not recommended to subclassify HGUC on urinary tract cytopathology alone. However, occasionally,

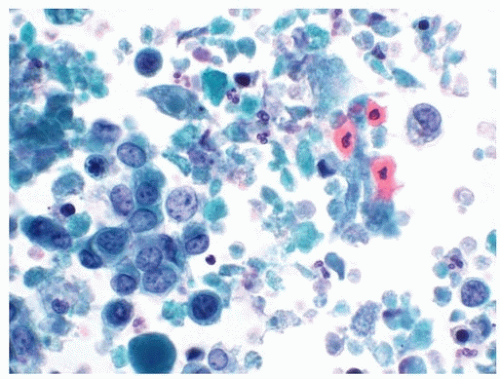

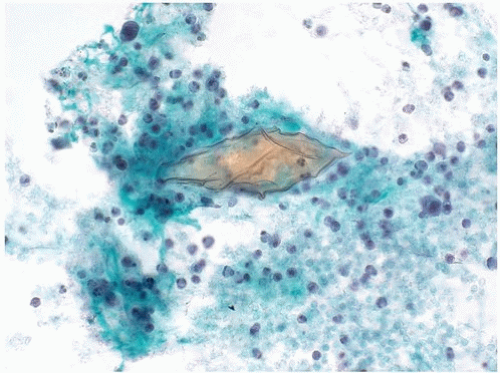

HGUC will be found with glandular, squamous, or small cell differentiation on urinary tract cytomorphology. Because these variants are the most commonly seen and possess distinct cytomorphological features, it is recommended that these be noted when seen. Given the difficulty of distinguishing these lesions from primary or secondary lesions when an HGUC component is not identified, it is only recommended to make this diagnosis when HGUC cells are present. For instance, in a urine specimen containing entirely carcinoma with squamous differentiation, it is impossible to distinguish a primary or secondary squamous cell carcinoma from an HGUC with squamous differentiation unless HGUC cells without squamous differentiation are also present (Fig. 14.3). Malignant or atypical specimens without a definite urothelial component should be classified under the “Other” category using descriptors such as “carcinoma with squamous features” or “atypical squamous cells.”

HGUC will be found with glandular, squamous, or small cell differentiation on urinary tract cytomorphology. Because these variants are the most commonly seen and possess distinct cytomorphological features, it is recommended that these be noted when seen. Given the difficulty of distinguishing these lesions from primary or secondary lesions when an HGUC component is not identified, it is only recommended to make this diagnosis when HGUC cells are present. For instance, in a urine specimen containing entirely carcinoma with squamous differentiation, it is impossible to distinguish a primary or secondary squamous cell carcinoma from an HGUC with squamous differentiation unless HGUC cells without squamous differentiation are also present (Fig. 14.3). Malignant or atypical specimens without a definite urothelial component should be classified under the “Other” category using descriptors such as “carcinoma with squamous features” or “atypical squamous cells.”

NEGATIVE FOR HIGH-GRADE UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA

Normal and Background Components

The typical components of a urinary tract specimen depend on the specimen type. Voided urine specimens often contain contaminating squamous cells and flora from outside the urinary tract. In some instances, squamous cells may greatly outnumber the urothelial cells. It is therefore critical to

be familiar with urothelial cell morphology and examine these cells rather than becoming distracted by the contaminating squamous component. Washing and catheterized specimens should only contain urinary tract elements, and the specimen should be interpreted in this context. Because instrumentation is disruptive to the urinary tract lining, these specimens typically contain a large number of urothelial tissue fragments while voided urine specimens rarely contain urothelial tissue fragments.

be familiar with urothelial cell morphology and examine these cells rather than becoming distracted by the contaminating squamous component. Washing and catheterized specimens should only contain urinary tract elements, and the specimen should be interpreted in this context. Because instrumentation is disruptive to the urinary tract lining, these specimens typically contain a large number of urothelial tissue fragments while voided urine specimens rarely contain urothelial tissue fragments.

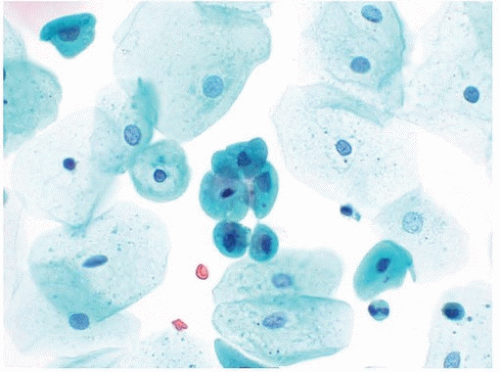

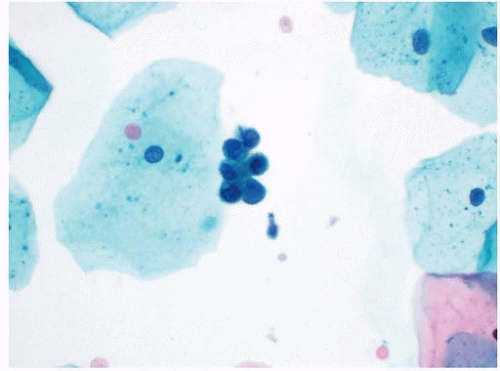

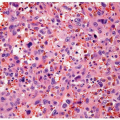

Normal urothelial cells are seen as parabasal-type cells and umbrella cells and in tissue fragments that may contain a mixture of these two cell types. The parabasal-type cell is the most common type and is similar to parabasal cells seen in cervical Pap tests (Fig. 14.4). In a urine specimen, the assumption is that parabasal-type cells are from the urinary tract because typically only superficial squamous cells contaminate urinary tract specimens. Parabasal-type cells have dense cytoplasm with regular cytoplasmic borders and contain a central small nucleus. They may loosely associate together and form cell clusters that mimic true tissue fragments.

Umbrella cells have abundant cytoplasm that may appear amphophilic. It is not unusual for umbrella cells to be binucleated, and rarely, umbrella cells may be packed with numerous nuclei. The size of umbrella cells may be distracting, but they typically do not contain features of HGUC. However, on occasion, HGUC specimens may contain enlarged cells with abundant cytoplasm and multiple nuclei with hyperchromasia and irregular nuclear borders. Given their high N/C ratios, these malignant

cells typically do not meet the criteria of HGUC though other cells found in the specimen often do.

cells typically do not meet the criteria of HGUC though other cells found in the specimen often do.

Benign-appearing urothelial issue fragments are common in instrumented specimens and may occasionally be seen in voided urine specimens (Fig. 14.5). One major challenge in urinary tract cytology is the interpretation of tissue fragments, as the cellular overlap in fragments makes it difficult to evaluate important cytomorphological features such as hyperchromasia and N/C ratios. Furthermore, the intercellular junctions allow physical forces to be exerted across the cells, resulting in changes in cellular shapes. Therefore, the threshold for identifying atypia in urothelial tissue fragments should be higher than that for individual cells. This decision can be very subjective and is one reason why the evaluation of individual urothelial cells is a more critical task.

Renal tubular cells are occasionally shed and subsequently found in voided urine specimens. Although small, these cells typically appear hyperchromatic and have irregular nuclear borders. These features occasionally result in renal tubular cells being diagnosed as atypical urothelial cells. Renal tubular cells can usually be distinguished from urothelial cells by their very small size and high N/C ratios. While they may be found singly, renal tubular cells often form small clusters with hobnailed borders (Fig. 14.6). When seen together with casts, renal tubular cells may suggest that a patient with new-onset hematuria may have upper tract disease other than malignancy.

Degenerative changes are common in voided urine specimens. The changes are tremendously variable and unpredictable. Some cells may have

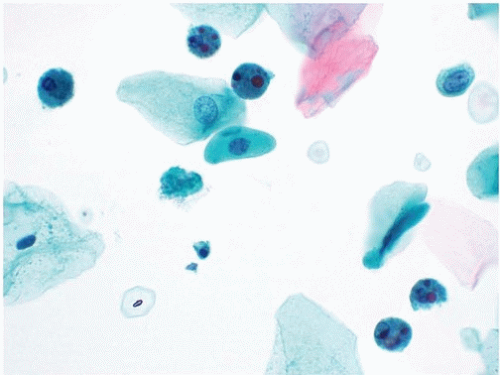

loss of cytoplasm, while other cells may have increased cytoplasm. Nuclear borders may become indistinct, or the nucleus may shrink and become pyknotic. The most well-described degenerative change is the presence of Melamed-Wolinska bodies, seen as dense and spherical cytoplasmic inclusions that appear homogenously red or green on the Pap stain (Fig. 14.7)

(20). Identifying the amount of degeneration present in a urinary tract specimen is important for two reasons. First, benign cells with degenerative changes may be flagged as atypical if they assume features that mimic HGUC. On the other hand, degenerated HGUC cells may lose diagnostic features. A urinary tract specimen may contain numerous HGUC cells, but extensive degeneration may mean rare-to-few HGUC cells meet the diagnostic criteria for HGUC. Degenerated HGUC cells often have pyknotic nuclei and expanded cytoplasm, resulting in N/C ratios below 0.7.

loss of cytoplasm, while other cells may have increased cytoplasm. Nuclear borders may become indistinct, or the nucleus may shrink and become pyknotic. The most well-described degenerative change is the presence of Melamed-Wolinska bodies, seen as dense and spherical cytoplasmic inclusions that appear homogenously red or green on the Pap stain (Fig. 14.7)

(20). Identifying the amount of degeneration present in a urinary tract specimen is important for two reasons. First, benign cells with degenerative changes may be flagged as atypical if they assume features that mimic HGUC. On the other hand, degenerated HGUC cells may lose diagnostic features. A urinary tract specimen may contain numerous HGUC cells, but extensive degeneration may mean rare-to-few HGUC cells meet the diagnostic criteria for HGUC. Degenerated HGUC cells often have pyknotic nuclei and expanded cytoplasm, resulting in N/C ratios below 0.7.

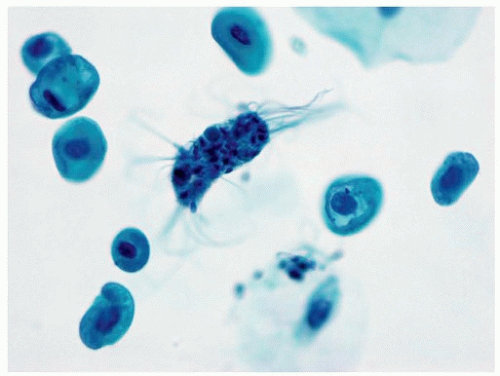

Background components in a urinary tract specimen include bacteria, fungal elements, spermatozoa, proteinaceous debris, red blood cells, casts, and crystals. While these factors are not necessarily normal and may represent a pathological process, they can distract from the primary goal of excluding HGUC, and in most instances, other laboratory tests are more appropriate for their clinical correlation. On occasion, macrophages may engulf spermatozoa, forming spermiophages, which can be distracting in urinary tract specimens (21) (Fig. 14.8).

Microbiological organisms may be contaminants from outside the urinary tract; a small number of organisms may grow into large colonies after specimen production and thus not correlate with a clinical infection. Occasionally, significant infections are present, which indicate a clinically relevant infection. The morphology of cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus infections is similar to that seen elsewhere, and these should be noted (Fig. 14.9). The most common parasites seen in urine specimens are contaminants from the gastrointestinal tract and include Enterobius vermicularis (22). Among patients traveling or living in endemic areas, Schistosoma haematobium may be seen in urinary tract specimens (Fig. 14.10). There is

a strong association between this organism and squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder; however, squamous cell carcinoma may arise in the bladder in the absence of such infection, and the organism is rarely seen in laboratories outside the endemic areas. Vegetable material, typically present as

a contaminant from outside the urinary tract, may sometimes be mistaken for parasite ova (23). It is therefore important to be familiar with the morphology of the most common gastrointestinal parasites in the region of practice.

a strong association between this organism and squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder; however, squamous cell carcinoma may arise in the bladder in the absence of such infection, and the organism is rarely seen in laboratories outside the endemic areas. Vegetable material, typically present as

a contaminant from outside the urinary tract, may sometimes be mistaken for parasite ova (23). It is therefore important to be familiar with the morphology of the most common gastrointestinal parasites in the region of practice.

Low-Grade Urothelial Neoplasia

LGUN correlates with a histological diagnosis of urothelial papilloma, papillary urothelial neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (PUNLMP), and low-grade urothelial carcinoma. It remains controversial whether such lesions can be diagnosed with enough accuracy that they deserve their own category or top-line diagnosis in urinary tract cytopathology. Because the negative category in the TPS is Negative for HGUC, specimens containing cytomorphological features that suggest LGUN without features of HGUC belong in this category. A note can be placed that states that features suggestive of LGUN are present. Cytomorphological features that have been reportedly associated with LGUN include three-dimensional cellular clusters, increased number of urothelial cells, cytoplasmic heterogeneity, and a slightly increased N/C ratio (24, 25, 26). While some cytopathologists believe in some instances they can make an unequivocal diagnosis of LGUN, most evidence suggests that LGUN diagnoses in urinary tract cytopathology have poor PPV, sensitivity, and reproducibility (4, 16, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32). Given the extensive cytomorphological overlap between LGUN, benign reactive changes, and HGUC, this chapter’s authors do not recommend making an unequivocal diagnosis of LGUN. However, the TPS does allow for a top-line diagnosis of LGUN only in rare instances when a papillary cluster containing a fibrovascular core is present, in the absence of any cytomorphological features of HGUC.

Although urinary tract cytology has poor accuracy for LGUN, it is acknowledged that LGUN can produce cytomorphological changes that can be identified in urinary tract specimens. These changes typically become more pronounced as the grade and size of the lesion increase—for instance, a large low-grade urothelial carcinoma is more likely to produce atypical findings than a small PUNLMP. Most often, these changes are mild and cannot be distinguished from reactive changes, resulting in an atypical or indeterminate diagnosis. In some instances, true papillary fragments may be identified, which indicate the presence of a papillary neoplasm of indeterminate grade (Fig. 14.11). On occasion, the cytomorphological atypia may approach that of HGUC and a diagnosis of Suspicious for HGUC (SHGUC) may be rendered (see below).

Urothelial Tissue Fragments

The presence of urothelial tissue fragments in urinary tract specimens can often be explained by instrumentation, for instance, in a bladder washing specimen or in a patient with a urinary catheter. In other instances, pathophysiologic factors such as urolithiasis (either clinically detectable or inapparent) or infection may damage the tract and release urothelial

tissue fragments into voided urine specimens. Other factors, such as recent exercise and prostatic massage, have been associated with urothelial tissue fragments in voided urine specimens. In most instances, the presence of urothelial tissue fragments cannot be identified (33).

tissue fragments into voided urine specimens. Other factors, such as recent exercise and prostatic massage, have been associated with urothelial tissue fragments in voided urine specimens. In most instances, the presence of urothelial tissue fragments cannot be identified (33).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree