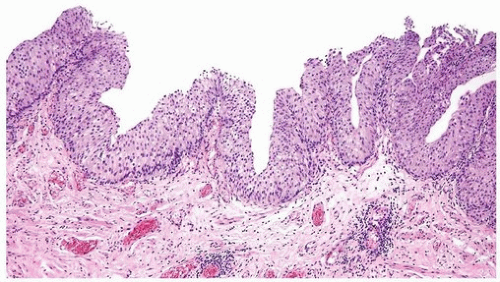

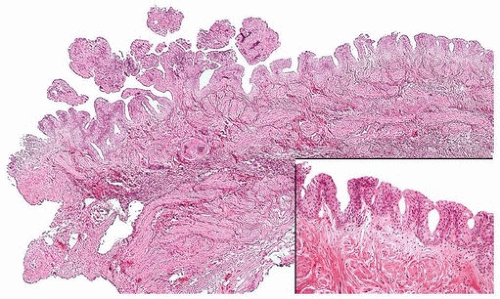

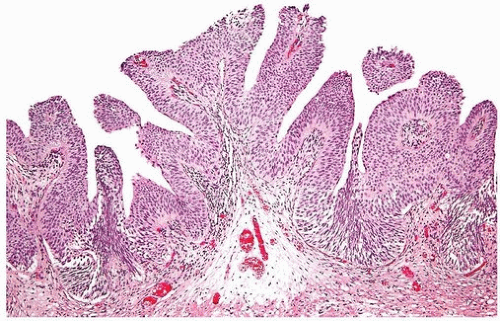

papillary urothelial neoplasms by lack of true fibrovascular cores within the hyperplastic mucosa, lack of complex arborization, and hence the absence of the appearance of “detached” papillary fronds (Figs. 3.5, 3.6). It is distinguished from low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma by lack of cytologic abnormality.

TABLE 3.1 The World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology Consensus Classification of Papillary Urothelial (Transitional Cell) Lesions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

TABLE 3.2 Histologic Features of Papillary Urothelial Lesions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

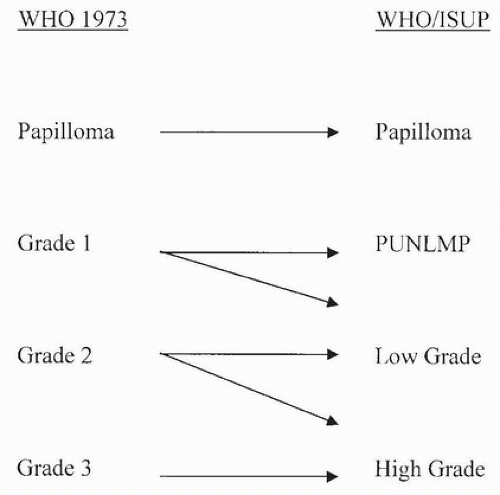

grades of carcinoma (grades 1, 2, and 3) (10). A major limitation of the WHO (1973) grading system was the lack of precise definition of the various grades and lack of specific histologic criteria. The following statement is the sole description of the difference between WHO grades 1, 2, and 3 as written in the original WHO (1973) system: “Grade 1 tumors have the least degree of anaplasia compatible with the diagnosis of malignancy. Grade 3 applies to tumors with the most severe degrees of cellular anaplasia, and Grade 2 lies in between.” In December 1998, members of WHO and ISUP published the WHO/ISUP consensus classification of urothelial (transitional cell) neoplasms of the urinary bladder (1). This new classification system arose out of the need to develop a more detailed classification system for bladder neoplasia and because many of the tumors classified

as “transitional cell carcinoma, grade 1” had no potential for malignant behavior once completely excised. In 2004, WHO revised its classification of urothelial tumors, adopting the WHO/ISUP system, resulting in a unified grading system for urothelial tumors (16). Because these systems are identical, in this text, the grading system is referred to as the WHO/ISUP system. The WHO 2016 blue book continues to endorse this classification system.

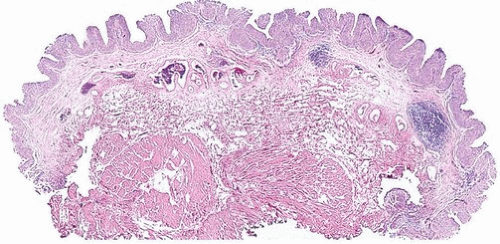

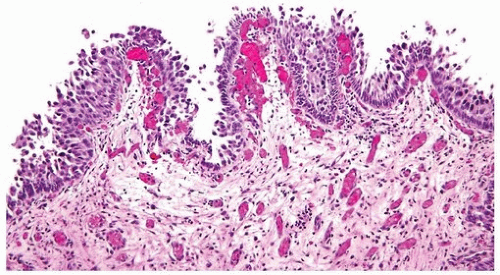

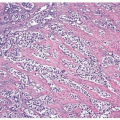

FIGURE 3.5 Papillary urothelial hyperplasia (right and inset) adjacent to urothelial papilloma (left). |

FIGURE 3.6 Papillary urothelial hyperplasia starting to develop branched fronds and “detached-appearing” papillary fronds diagnostic of early urothelial papilloma. |

carcinoma. In the old WHO (1973) system, a large percentage of patients with noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinomas were called grade 2, an ambiguous group that the urologists did not know how to treat. In the WHO/ISUP grading system, these grade 2 tumors can be segregated roughly equally into low- and high-grade cancers with correspondingly low and high risks of progression (24, 25, 26). When WHO (1973) grade 2 tumors are reclassified as high-grade tumors, they show molecular aberrations usually associated with cancers of higher grade and poor outcome, further supporting that the WHO (1973) grade 2 tumors form a heterogeneous group that can be subdivided into low- and high-grade cancer (27).

FIGURE 3.8 Relationship of WHO (1973) to WHO (2003)/ISUP classification of papillary urothelial tumors. |

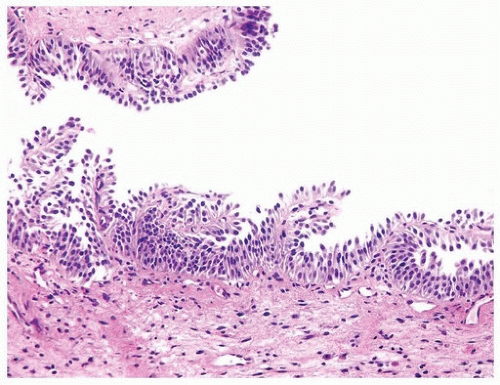

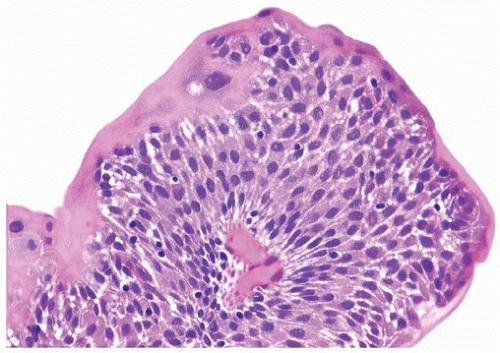

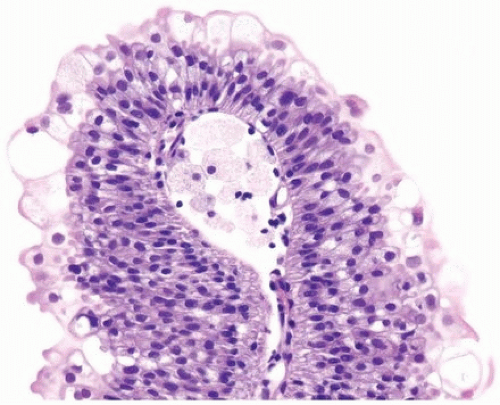

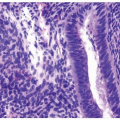

of urothelium. There is no need to count the maximum number of cell layers, as long as it is not obviously thicker than the normal urothelial lining. In most cases, the urothelium is tightly cohesive, although in some cases, there may be the appearance of discohesion. Umbrella cells vary in their morphology from being inconspicuous, to being cuboidal with slightly enlarged nuclei and paler cytoplasm, to having a hobnail appearance with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Occasional cases of urothelial papilloma have an umbrella cell layer with prominent vacuolization. Single, enlarged umbrella cells may also drape themselves over several underlying urothelial cells, where the umbrella cell nuclei may

demonstrate degenerative atypia. Urothelial atypia, other than that which can be seen in umbrella cells, excludes the diagnosis of papilloma. Mitotic figures are absent.

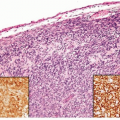

FIGURE 3.10 Urothelial papilloma. There is a consistent umbrella cell layer in which the cells appear slightly enlarged: this feature does not argue against a diagnosis of papilloma. |

totaling 153 patients, only 1 patient experienced stage progression; invasive urothelial carcinoma was found extending out of the bladder 4 years after the diagnosis of papilloma (38, 40, 41, 42). A caveat to this exceptional case is that the patient was immunosuppressed following renal transplantation.

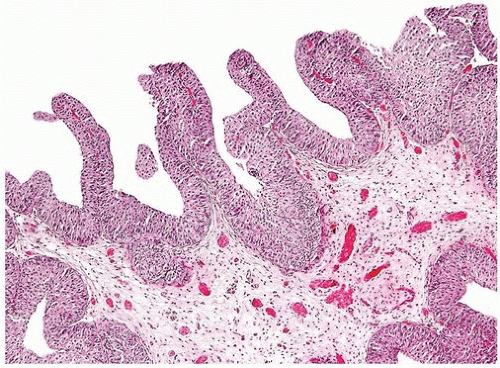

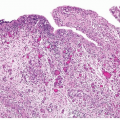

compared to papilloma (Figs. 3.17, 3.18, 3.19, 3.20, 3.21, 3.22) (efigs 3.46-3.76). Having a category of PUNLMP avoids labeling a patient as having cancer, which has psychosocial and financial (e.g., insurance) implications, although since it is not labeled as an unequivocal benign lesion (e.g., papilloma), its diagnosis implies that the patient should be adequately followed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree