USUAL OR CONVENTIONAL TYPE OF UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA

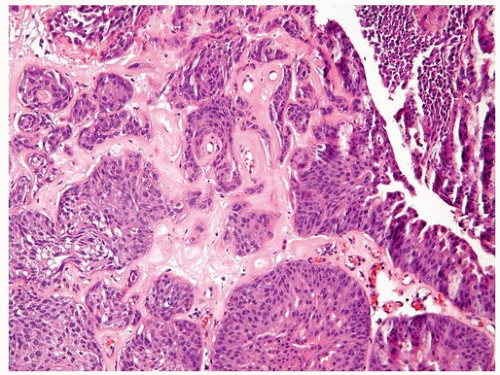

Invasive urothelial carcinoma may present as a polypoid, sessile, ulcerated, or infiltrative lesion in which the neoplastic cells invade the bladder wall as nests, cords, trabeculae, small clusters, or single cells that are often separated by a desmoplastic stroma. The tumor sometimes grows in a more diffuse, sheet-like pattern, but even in these cases, focal nests and clusters are generally present. Occasionally, carcinomas are associated with a pronounced chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, which partially or substantially obscures the underlying tumor cells. In some instances, the inflammation may appear to be an integral component of the neoplasm and mimic the distinctive lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the bladder (see

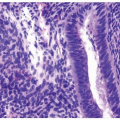

Chapter 6). The neoplastic cells in typical or conventional patterns of invasive urothelial carcinoma are usually of moderate size and have modest amounts of pale to dense eosinophilic cytoplasm (

Fig. 5.1). Sometimes, tumors with a more nest-like architecture, eosinophilic cytoplasm in tumor cells, and prominent stromal vascularity between nests may mimic a paraganglioma (see

Chapter 12). In some tumors, the cytoplasm is more abundant and may be clear or strikingly eosinophilic. The presence

of clear cells, with rare exceptions, is focal and should not lead to the diagnosis of clear cell adenocarcinoma, which has a very typical histology. Invasive carcinomas, particularly early and/or with limited invasion into the lamina propria, may be associated with retraction artifact. This finding when conspicuous should not be mistaken for vascular-lymphatic invasion or micropapillary carcinoma, which has distinctive definitional features and prognostic and possibly therapeutic significance (see

Chapter 6). Some cases elicit a stromal response, which may occasionally be prominent and elicit a pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic appearance (not to be mistaken with a biphasic component of sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma).

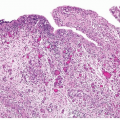

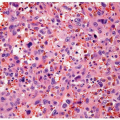

Invasive tumors are almost all high grade, although there is a spectrum of some cases exhibiting marked anaplasia; focal tumor giant cell formation may be seen. Typically, most cases show nuclear pleomorphism, markedly irregular cellular borders, and chromatin distribution with frequent mitoses (helpful in the distinction from prostatic adenocarcinoma, which has more monotonous-appearing nuclei and which may secondarily invade the bladder, and paraganglioma involving the bladder, which has spotty endocrinetype atypia). Only a small minority of invasive urothelial carcinomas has a low-grade histology (see

Chapter 6 for a description of nested variant of urothelial carcinoma) (

Fig. 5.2). In contrast to noninvasive low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma, nested variant of urothelial carcinoma typically lacks an inflammatory or desmoplastic stromal reaction, usually does not have an overlying papillary component, lacks more irregular shaped nests, and does not consist of small clusters of cells with retraction artifact (

1). However, in these cases, the outcome is not determined by tumor grade but rather by stage. By the World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathologists (WHO/ISUP) classification, invasive tumors are graded as low grade and high grade. Features indicative of the urothelial

character of cells of urothelial carcinoma include the presence of longitudinal nuclear grooves that are often appreciable in low-grade tumors but are rarely seen in high-grade tumors.

Approximately 10% of urothelial carcinomas contain foci of glandular, and approximately 40% to 60% show variable amounts of squamous differentiation (see

Chapters 8 and

9). This may not reflect the actual frequency as this information is not consistently or accurately recorded by pathologists. Glandular differentiation is usually in the form of small tubular or gland-like spaces in conventional urothelial carcinoma (urothelial carcinoma with gland-like lumina) or as a histology similar to enteric adenocarcinoma (

2,

3). Rare mucin-producing cells in invasive carcinoma or cytoplasmic mucin may be demonstrated in up to 60% of cases by histochemical stains, although these features do not qualify for glandular differentiation and do not need to be reported. Rarely, a coexistent signet ring cell or mucinous component may be present.

To designate squamous differentiation, one must see clear-cut evidence of squamous production (intracellular keratin, intercellular bridges, or keratin pearls), and the degree of squamous differentiation, when present, usually parallels the grade of the urothelial carcinoma. While the presence of squamous differentiation should be reported, the mere presence of more dense eosinophilic cytoplasm or “squamoid” appearance does not qualify for squamous differentiation and should not be recorded.

In general, urothelial carcinomas have a relatively nondescript morphology (“patternless pattern”), which when viewed in isolation cannot be differentiated from poorly differentiated carcinomas of other types. Therefore, the presence of divergent differentiation such as squamous or glandular differentiation in a poorly differentiated neoplasm, particularly at metastatic

sites and in the context of a bladder primary, should suggest the possibility of urothelial differentiation. To designate a bladder tumor as squamous cell or adenocarcinoma, a pure or almost pure histology of squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma is required. The presence of some percentage of squamous and glandular differentiation in urothelial carcinomas has generally been thought of as lacking any clinical significance. In stage-matched cases, the outcome of typical urothelial carcinoma is similar to those with aberrant differentiation (

4). However, some studies have suggested that these variants may be more resistant to chemotherapy or radiation therapy than pure urothelial carcinoma, but this has not been confirmed (

5,

6). Squamous differentiation in biopsies or transurethral resection has been associated with locally advanced disease at cystectomy (

7). From a practical viewpoint, we do make note of prominent squamous or glandular differentiation in urothelial carcinoma by using diagnostic terminology such as “invasive urothelial carcinoma with prominent squamous (40%) and glandular (25%) differentiation,” providing some estimate of the amount of differentiation. In cases of metastatic tumor, knowledge of the presence and percentage of divergent differentiation may be useful to facilitate comparison with the primary. Recent gene sequencing studies suggest that invasive urothelial carcinoma may have two unique profiles—basal/squamous-like, luminal and p53-like— with potentially differing outcomes associated with the basal subtype including poor responsiveness to chemotherapy. Tumors with basal subtype have squamous or squamoid morphology and express CK5/6 instead of CK20. These studies are preliminary, and currently, reporting of these subtypes or performing immunostains to diagnose them is not recommended (

8,

9,

10,

11).

A subset of invasive urothelial carcinomas may exhibit vascular invasion. This parameter should be diagnosed with care, because invasive urothelial carcinomas, particularly those with limited or early invasion, frequently show retraction artifact, which mimics vascular-lymphatic invasion. In two studies, only 14% and 40% of cases originally diagnosed with vascular invasion on the basis of morphology could be proven by immunohistochemistry (

12,

13). Criteria for recognition of vascular invasion are outlined later in this chapter, and its prognostic significance especially in node-negative carcinomas is uncertain (

14) (see

Chapter 7 for prognostic significance).

In addition to the morphology described earlier, invasive urothelial carcinoma has a propensity for a myriad of other patterns of divergent differentiation (e.g., small cell carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma) or variation in histology (micropapillary, microcystic, nested) in approximately 10% of cases. These are described in detail in Chapter 6.

IMMUNOPROFILE OF INFILTRATING UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA

Immunohistochemistry plays a valuable role in confirming urothelial differentiation in select settings such as (a) confirming urothelial origin in a metastatic tumor in a patient with history of upper urothelial tract or bladder

disease; (b) differentiating a bladder primary from high-grade prostatic carcinoma and other high-grade malignancies in the pelvis (colorectal, ovarian, cervical, etc.); (c) proving urothelial differentiation in unusual variants of bladder cancer and their accurate distinction from other mimickers; (d) in the differential diagnosis with other epithelioid tumors involving the bladder, for example, paraganglioma, PEComa, epithelioid leiomyosarcoma, etc. While a number of markers are available, only a select few should be performed based on the differential diagnosis (

15).

Urothelial carcinomas are typically CK7 (up to 100%) and CK20 positive (40% to 70%), GATA3 positive, and uroplakin II positive (

16). Uroplakin III is less sensitive and recently fallen out of favor due to the better sensitivity of GATA3 (65% to 90%) and increased specificity of uroplakin II (77%). It is important to remember that GATA3 may be positive in paraganglioma and nephrogenic adenoma, two important differential diagnostic considerations in bladder neoplasia. p63, high molecular weight cytokeratin, CK5/6, and thrombomodulin are frequently positive in urothelial tumors but lack specificity. S100P is emerging as a useful marker in urothelial tumors, but like GATA3 is positive in several other tumor types (

15,

16).

STAGING OF BLADDER CANCER

Stage is the most powerful prognostic indicator in urothelial carcinoma and is a major defining parameter in the management of this disease (

4). The TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) staging system defines T1 tumors as those invading into the lamina propria but not the muscularis propria (

17). Even though several studies have shown that T1 tumors bear a less favorable prognosis than Ta (noninvasive) neoplasms (

18,

19,

20), clinically Ta and T1 tumors are usually lumped together by urologists under the term

superficial bladder tumors, partially because these two stages traditionally have been managed conservatively. Another possible factor contributing to the clinician’s rationale in grouping Ta and T1 tumors as superficial is the pathologists’ inability to always accurately recognize lamina propria invasion (

21,

22). We strongly discourage the use of the term

superficial to describe T1 tumors since contemporary series in which great care was taken to classify Ta and T1 correctly have shown clear differences in progression rates (

23,

24). Tumors with involvement of the muscularis propria and beyond (pT2-4 tumors) are usually managed with definitive surgical therapy (i.e., cystectomy) or radiation therapy with or without adjuvant therapy. Three to seven percent of patients treated by cystectomy will have lymph node metastases, and the clinical outcome varies considerably. Patients with CIS and lymphovascular invasion along with muscularis propria invasion, at primary transurethral resection, tend to have a more adverse outcome (

25).

Traditionally, approximately 10% of bladder carcinomas, treated by cystectomy, have no evidence of residual disease (pT0). The incidence of

pT0 disease is increasing as several high-risk noninvasive bladder cancers may be treated by radical cystectomy. These include patients with highgrade pT1 tumors, multiple recurrent high-grade tumors, and high-grade tumors with concomitant CIS. In addition, NCCN guidelines call for a repeat transurethral resection for high-risk tumors prior to excisional surgery. Systemic neoadjuvant therapy has also increased the percentage of pT0 disease at cystectomy. Currently, there are no universally accepted guidelines on gross dissection of cystectomy specimens without obvious invasive cancer. All mucosal alterations, prior surgical sites and ulcerations submitted in their entirety, and adequate sampling from different areas of the bladder are necessary. Patients with pT0 disease (posttransurethral resection of bladder tumor [TURBT] or neoadjuvant therapy) have markedly improved and overall disease-specific survival compared to cystectomy specimens with residual disease (

26,

27).

Before discussing lamina propria (T1) and muscularis propria (T2 and T2+) invasion, it is important to be aware of the type of specimens encountered in bladder pathology and some histologic aspects of the bladder wall that are pertinent for the discussion of invasion.

Most small bladder tumors (usually less than 1 cm in size) can frequently be excised by cold-cup biopsies. This procedure yields specimens in which the cellular architecture is mostly preserved and orientation is easier to maintain after embedding. The resulting hematoxylin and eosin sections show the urothelial neoplasm, the lamina propria, and often superficial muscularis propria with orientation maintained, thus facilitating assessment of invasion (

28). Larger tumors (usually greater than 1 cm) usually require hot loop resection (TURBT), in which the urologist attempts to include a generous sample of the underlying muscularis propria to enable adequate pathologic staging. The specimens rendered by this procedure are often fragmented, heavily cauterized, and difficult to orient. Sections from these specimens are complicated by thermal artifact, tangential sectioning, and disruption of the tumor and normal architecture. Changes related to prior TUR may also add to the difficulty. While examining both types of specimens, it is important to note the presence or absence of muscularis propria in the specimen to assess involvement of it by neoplasia and to provide feedback to the urologist regarding adequacy of resection.

The lamina propria is a compact layer of fibrovascular connective tissue. Smooth muscle actin staining has revealed a continuous band of ill-defined, haphazardly oriented, compact spindle cells that are immediately subjacent to the urothelium in all cases. This layer has been referred to as suburothelial band of myofibroblasts. Beneath this layer, in most instances, the lamina propria is further divided by a thin layer of smooth muscle fibers (muscularis mucosae), which may be absent, discontinuous, or rarely complete. Because it is commonly incomplete, it is best to regard the underlying connective tissue, superficial to the muscularis propria, as deep lamina propria rather than submucosa. These anatomic landmarks

may be entirely replaced by dense connective tissue at sites of prior biopsy. It was not until the 1980s that the muscularis mucosae layer of the urinary bladder was described (

29,

30,

31), alerting pathologists and urologists of the importance of recognizing it and differentiating it from the underlying compact smooth muscle bundles of muscularis propria. Muscularis mucosae fibers are usually thin, often discontinuous, wispy, and wavy fascicles of smooth muscle, which are frequently associated with large-caliber blood vessels and surrounded by loose fibroconnective tissue. Most studies have identified some degree of this layer in 94% to 100% of cystectomy specimens (

30,

31) and in approximately 18% to 83% of specimens from biopsies or TURBT (

23,

32). Topographical variations in caliber of muscularis mucosae muscle exist between different regions of the bladder (

33), and the lamina propria vascular plexus may not be consistently associated with muscularis mucosae muscle. Muscularis mucosae muscle bundles may be thicker (hypertrophic form) or rarely assume the caliber of muscularis propria muscle bundles. This is commonly the case along the wall of bladder diverticula. Distinction is possible by location in the lamina propria and being distinct from deeper muscularis propria muscle (

33). Muscularis propria fascicles, on the other hand, are usually thick and compact, divided into distinct bundles surrounded by perimysium. The muscularis propria has a different morphology in the bladder neck and trigone (see

Chapter 1). Occasionally, muscularis mucosae bundles undergo hypertrophy especially after biopsy or at the base of the tumor, and in such situations, the distinction between muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria, especially in biopsy or TURBT specimens, may be difficult. The deep (outer half) muscularis propria often rests on the perivesical fat. The boundary between them is not abrupt. Fat is present in all layers of the bladder beneath the urothelium; the frequency and amount increase from the superficial lamina propria to the deep lamina propria and to the muscularis propria (

34).