Squamous Lesions

SQUAMOUS METAPLASIA

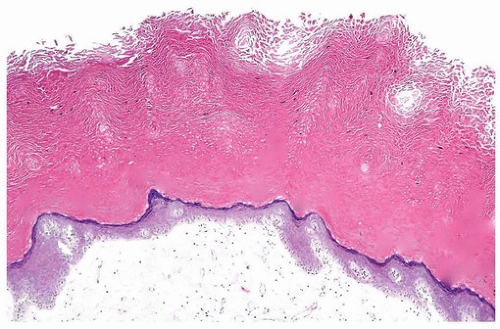

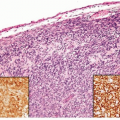

Squamous epithelium, particularly in the area of the trigone, is a common finding in women (Fig. 9.1) (also see Chapter 1). Trigonal squamous epithelium in women represents a normal histologic variant occurring under hormonal influence unassociated with local injury. Chronic irritation, such as with recurrent urinary tract infections, long-term catheterization, urinary lithiasis, chronic urinary tract obstruction, fistulae, bladder exstrophy, neurogenic bladder, prior bladder surgery or radiation, parasite infection, and vitamin A deficiency, can result in keratinizing squamous metaplasia (1). In this condition, the squamous epithelium exhibits parakeratosis and hyperkeratosis and may even acquire a granular layer (Fig. 9.2). This metaplastic epithelium is not preneoplastic per se, but under some circumstances, especially when extensive and involving large regions of the bladder, it may lead to squamous carcinoma (2). This is the sequence of events, for example, in patients with long-standing schistosomiasis of the urinary bladder or, in the case of squamous carcinoma, arising in bladder diverticula (3, 4, 5). In these cases, it may be possible to observe keratinizing squamous metaplasia and dysplastic changes adjacent to in situ and invasive squamous carcinoma. The pathologist is obligated to mention the presence and extent of keratinizing squamous metaplasia in a transurethral biopsy specimen. Khan and colleagues (6) described their experience with 34 patients with keratinizing squamous metaplasia. Although the extent of involvement correlated with subsequent risk of carcinoma, any degree of keratinizing squamous metaplasia is a significant risk factor for the development of subsequent carcinoma as well as other complications such as bladder contracture and obstruction (6). Lesions are treated by transurethral resection and close follow-up to rule out progression to carcinoma. In some cases, the metaplasia can resolve, especially if the inciting cause of injury has been removed (1). If extensive squamous metaplasia is present, a comment that sampling of all lesional tissue is recommended because of the association with dysplastic, in situ or invasive squamous, or rarely urothelial lesions.

VERRUCOUS SQUAMOUS HYPERPLASIA

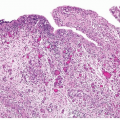

Verrucous squamous hyperplasia consists of a spiking or church spirelike squamous hyperplasia (Fig. 9.3). Marked hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and elongation of the rete pegs are also present, but the lesions lack the broad invasive tongues seen with verrucous carcinoma. Although this lesion has only been relatively recently reported in the urinary bladder, verrucous squamous hyperplasia is well recognized in the oral cavity and upper respiratory tract. In these sites, verrucous squamous hyperplasia is an irreversible lesion with a considerable risk for evolving into verrucous or other forms of squamous cell carcinoma. In a study of this lesion in the bladder, clinical follow-up information was available in five cases of verrucous squamous hyperplasia (6). One patient developed conventional

invasive squamous cell carcinoma, and another patient was subsequently diagnosed with urothelial carcinoma in situ (CIS). These results suggest that verrucous squamous hyperplasia may represent a premalignant lesion or may be associated with premalignant lesions in the bladder and should be treated and followed accordingly. In a series of invasive squamous cell carcinoma, 7% of patients had squamous hyperplasia in background mucosa (7).

invasive squamous cell carcinoma, and another patient was subsequently diagnosed with urothelial carcinoma in situ (CIS). These results suggest that verrucous squamous hyperplasia may represent a premalignant lesion or may be associated with premalignant lesions in the bladder and should be treated and followed accordingly. In a series of invasive squamous cell carcinoma, 7% of patients had squamous hyperplasia in background mucosa (7).

CONDYLOMA ACUMINATA

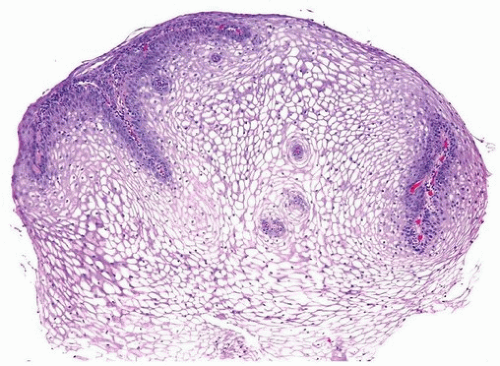

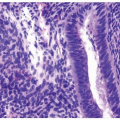

Condyloma acuminata are common sexually transmitted benign tumors caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) (Figs. 9.4, 9.5) (efigs 9.1-9.7). Condylomas are composed of thickened nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium arranged in verrucous folds with thin fibrovascular cores, typically lacking “free-floating” papillary fronds. There is cytoplasmic clearing around nuclei (koilocytosis) and with atypia restricted to crinkly mostly small nuclei, lacking hyperchromasia or mitoses unless accompanied by moderate to severe dysplasia. They occur most frequently on mucocutaneous surfaces of the external genitalia, perineum, and anus, but extension into the urethra is not uncommon, occurring in up to 20% of cases. On rare occasions, they may involve the bladder or even the ureters (8, 9, 10, 11). Most patients have associated extensive condyloma of the external genitalia. Isolated condyloma of the bladder often presents in immunosuppressed patients. Of the three cases of condyloma of the bladder reported by Del Mistro et al. (12), two occurred in immunocompromised patients. The three patients reported by Cheng et al. (13) were all associated with extensive condyloma in the external genitalia, and one of the patients had

follow-up studies showing multiple recurrence of condyloma. Condylomas of the bladder are refractory to conservative treatment and prone to multiple recurrences (12). There are also multiple case reports of condylomas in the urinary bladder associated with high-grade dysplasia, squamous, verrucous, or urothelial bladder cancer, warranting close follow-up of patients with bladder condylomas (7, 9, 14, 15). If one has as a differential diagnosis squamous papilloma versus condyloma of the bladder, in situ hybridization for low- and high-risk HPV may be performed, which will only be positive in condylomas.

follow-up studies showing multiple recurrence of condyloma. Condylomas of the bladder are refractory to conservative treatment and prone to multiple recurrences (12). There are also multiple case reports of condylomas in the urinary bladder associated with high-grade dysplasia, squamous, verrucous, or urothelial bladder cancer, warranting close follow-up of patients with bladder condylomas (7, 9, 14, 15). If one has as a differential diagnosis squamous papilloma versus condyloma of the bladder, in situ hybridization for low- and high-risk HPV may be performed, which will only be positive in condylomas.

FIGURE 9.5 Condyloma acuminatum (higher magnification of Fig. 9.4). |

SQUAMOUS PAPILLOMA

In 2000, Cheng and colleagues (13) described a series of seven cases of squamous papilloma of the bladder, five occurring in the urinary bladder and the others in the urethra (Figs. 9.6, 9.7). These lesions were characterized by a proliferation of mature and benign-appearing squamous epithelium surrounding a central fibrovascular core. Koilocytes were not present, and in situ hybridization for HPV was negative in all cases. Most of the patients were women, and none had history of genital, perianal, or perineal condyloma. In the five cases without prior urothelial carcinoma, subsequent biopsies showed repeated squamous papilloma in one case and

no evidence of disease in the other four cases. In a later study by Guo et al. (9), among four patients with bladder squamous papillomas who had follow-up, only one patient developed a low-grade urothelial carcinoma and the other three patients had no evidence of disease. The case with low-grade urothelial carcinoma on follow-up had a history of low-grade urothelial carcinoma that preceded the diagnosis of squamous papilloma, such that the recurrence of urothelial carcinoma in this patient is most likely unrelated to the squamous papilloma. Squamous papilloma appears to be a benign proliferative, non-HPV-associated squamous lesion without an appreciable risk factor for bladder cancer.

no evidence of disease in the other four cases. In a later study by Guo et al. (9), among four patients with bladder squamous papillomas who had follow-up, only one patient developed a low-grade urothelial carcinoma and the other three patients had no evidence of disease. The case with low-grade urothelial carcinoma on follow-up had a history of low-grade urothelial carcinoma that preceded the diagnosis of squamous papilloma, such that the recurrence of urothelial carcinoma in this patient is most likely unrelated to the squamous papilloma. Squamous papilloma appears to be a benign proliferative, non-HPV-associated squamous lesion without an appreciable risk factor for bladder cancer.

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

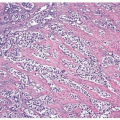

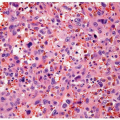

The diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma should be reserved for those tumors that are purely or almost entirely keratin forming and exhibiting intercellular bridges (Figs. 9.8, 9.9) (efigs 9.8-9.10). For urothelial tumors with variable amounts of squamous differentiation, the term urothelial carcinoma with squamous differentiation should be used (see Chapter 8 for general concepts regarding divergent [aberrant] differentiation). Squamous cell carcinoma occurs in two settings, one related to and the other not associated with schistosomal infections.

Schistosomal Associated Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Between 60% and 90% of carcinomas associated with urinary schistosomiasis are squamous cell carcinomas, with 5% to 15% being adenocarcinomas and the rest urothelial carcinomas (15, 16, 17, 18). Nitrates in the urine, particularly present in individuals living in agricultural areas where nitrate fertilizers are used liberally, may be reduced to carcinogenic nitrosamines as a result of

secondary bacterial infection. Other contributing factors include mechanical irritation of the bladder by the parasitic eggs, smoking, and pesticides. Squamous carcinoma used to be the most common form of bladder cancer in Egypt as a result of the association with schistosomiasis, yet other countries share a high incidence of schistosomal associated squamous cell carcinoma including Iraq, parts of Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Sudan. Although bladder cancer is still the most common cancer in males in Egypt, urothelial carcinoma is currently more common than squamous carcinoma corresponding to a decrease in schistosomal infections (16, 17, 18, 19, 20) (see Chapter 10).

secondary bacterial infection. Other contributing factors include mechanical irritation of the bladder by the parasitic eggs, smoking, and pesticides. Squamous carcinoma used to be the most common form of bladder cancer in Egypt as a result of the association with schistosomiasis, yet other countries share a high incidence of schistosomal associated squamous cell carcinoma including Iraq, parts of Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Sudan. Although bladder cancer is still the most common cancer in males in Egypt, urothelial carcinoma is currently more common than squamous carcinoma corresponding to a decrease in schistosomal infections (16, 17, 18, 19, 20) (see Chapter 10).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree