EPITHELIAL UTERINE TUMORS

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. In 2015, the American Cancer Society estimated there were 54,870 new cases and over 10,170 endometrial cancer–related deaths (1). Approximately 75% of women diagnosed with endometrial cancer are diagnosed at an early stage and have a 5-year overall survival of 74% to 91% (2). For women with stage III or IV disease, reported 5-year overall survival rates are 57% to 66% and 20% to 26%, respectively (2). This disease primarily affects women in their postmenopausal and perimenopausal years, and the average age at diagnosis is 61 years (2).

The main risk factors for endometrial cancer are age, obesity, diabetes, and exposure to excess estrogen without adequate opposition by progesterone. This includes the historical use of exogenous unopposed estrogen therapy, the use of estrogen agonists (such as tamoxifen), and physiological states that lead to excess endogenous estrogen. Excess endogenous estrogen can be found in women with obesity, chronic anovulation, early age at menarche, nulliparity, late age of menopause, and in the setting of rare estrogen-secreting tumors.

Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator that is used for chemoprevention of breast cancer and as a part of adjuvant therapy for estrogen-receptor–positive breast cancer; it may also be used to treat metastatic breast cancer. It acts as an antagonist on estrogen receptors in the breast but also has a weak agonist effect on the estrogen receptors in the endometrium. These estrogenic effects on the endometrium lead to a significant increase in the risk of developing endometrial cancer, with a relative risk of 2.13 and an absolute annual risk of about 2 per 1,000 patients taking tamoxifen (3). In a study by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP), women taking tamoxifen (20 mg/d) developed endometrial cancer at a rate of 1.6 per 1,000 patient years, compared to 0.2 per 1,000 patient years among women taking a placebo. At the same time, the 5-year survival rate from breast cancer was 38% higher among women taking tamoxifen compared to women in the placebo group. This suggested that the relatively small risk of developing endometrial cancer was outweighed by the greater survival benefit for women with breast cancer (4).

Obesity is a well-established risk factor for the development of endometrial cancer. A meta-analysis of 19 prospective studies showed that for every 5 kg/m2 increase in body mass index (BMI), a women’s risk of developing endometrial cancer significantly increases (5). One explanation for these findings is that women who are obese have higher levels of endogenous estrogen because of the conversion of androstenedione into estrone and the aromatization of androgens to estradiol, which occurs in the peripheral adipose tissue. There are additional proposed mechanisms for this association, including alterations in insulin signaling and insulin resistance, alterations in expression of circulating adipokines, as well as alterations in pathways involving inflammation (6,7,8). Obesity increases the risk of endometrial cancer in both post- and premenopausal women. In fact, the majority of young, premenopausal women diagnosed with endometrial cancer have a BMI greater than 30 (9).

Lynch syndrome is an autosomal dominant hereditary cancer syndrome characterized by an increased risk in endometrial cancer, colon cancer, and several other malignancies. It is associated with a germline defect in a DNA mismatch repair gene (MutL homolog 1 [MLH1], MutS homolog 2 [MSH2], MutS homolog 6 [MSH6], postmeiotic segregation 2 [PMS2]). Women who have Lynch syndrome have a 15% to 66% lifetime risk of developing endometrial cancer, a 15% to 68% lifetime risk of developing colon cancer, and a 1% to 20% lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer, depending on the specific mutation involved (10,11).

Except for patients who have been diagnosed with Lynch syndrome, there is insufficient evidence to support screening for endometrial cancer in asymptomatic women in the general population, even those with risk factors such as tamoxifen use, history of unopposed estrogen, obesity, or diabetes. The American Cancer Society currently recommends that all women be informed about the risks and symptoms of endometrial cancer at menopause. Women should alert their physicians of any unexpected bleeding or spotting in the postmenopausal years and abnormal uterine bleeding in the pre- or perimenopausal years.

The American Cancer Society recommends yearly screening with endometrial biopsy beginning at age 35 for women who are known to carry Lynch syndrome–associated mutations, those who have a family member known to carry this mutation, or women from families with an autosomal dominant predisposition to colon cancer in the absence of genetic testing for Lynch syndrome (12). Prophylactic hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy have been shown to be effective in decreasing the risk of endometrial and ovarian cancer and should be offered to women with Lynch syndrome after childbearing is complete (13).

The primary symptom of endometrial cancer is postmenopausal bleeding or abnormal uterine bleeding in pre- or perimenopausal women. A histologic diagnosis is most commonly obtained by office endometrial sampling or dilation and curettage.

Women with histologic diagnoses of endometrial hyperplasia often present with postmenopausal bleeding or menometrorrhagia. The risk factors associated with the development of endometrial hyperplasia, including obesity and unopposed estrogen, are similar to those associated with endometrial cancer (14). The World Health Organization defined endometrial hyperplasia based on two characteristics: (1) simple or complex glandular/stromal architectural pattern and (2) the presence or absence of nuclear atypia. The presence of nuclear atypia correlates highest with the risk of developing malignancy. In this spectrum, those with simple hyperplasia without atypia are least likely to develop endometrial carcinoma, while women with complex hyperplasia with atypia are most likely to develop carcinoma. In a long-term follow-up study conducted by Kurman et al, endometrial carcinoma occurred in simple, complex, simple atypical, and complex atypical hyperplasia in 1%, 3%, 8%, and 29% of cases, respectively (15). A report from one meta-analysis showing a wider range of risk of cancer progression based on four prospective follow-up studies is summarized in Table 32-1 (16).

| Hyperplastic Type | No. of Cases | Risk of Progression (%) | Mean Risk (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple hyperplasia | 164 | 0-10 | 4.3 |

| Complex hyperplasia | 193 | 3-22 | 16.1a |

| Simple hyperplasia with atypia | 27 | 7.8 | 7.4a |

| Complex hyperplasia with atypia | 151 | 29-100 | 47.0 |

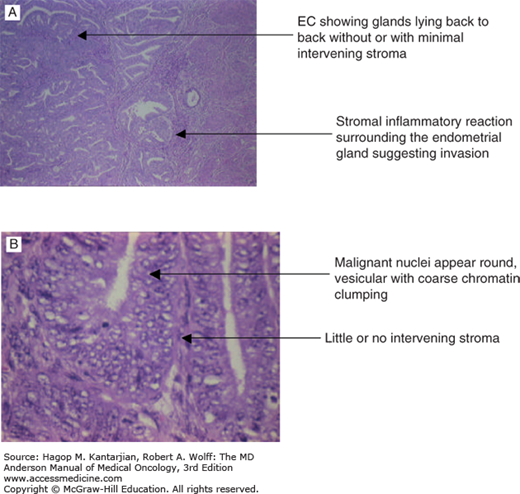

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma is the most common subtype of endometrial cancer, accounting for 75% to 80% of endometrial cancer. Endometrioid adenocarcinomas are graded 1 to 3, based on degree of differentiation. Grade 1 tumors are well differentiated, composed of glands resembling normal endometrial tissue (Fig. 32-1A). In less-differentiated tumors, glandular formations are less evident or are replaced with solid areas (Fig. 32-1B). The percentage of tumor consisting of these nonsquamous or nonmorular solid areas is the criterion for grading, with grade 1 having a 5% or less solid component, grade 2 having more than 5% but less than or equal to 50%, and grade 3 having greater than 50%. Notably, the presence of nuclear atypia that does not correlate with the architectural features should lead to a one-step upgrade of the tumor.

Papillary serous carcinomas are highly aggressive tumors that should be distinguished from other types of uterine carcinoma. Papillary serous carcinomas tend to occur in older women, are usually present in advanced stages, and represent 1% to 5% of cases. Deep myometrial invasion, extensive lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI), and extrauterine spread are common. Intraperitoneal involvement is often observed even when the primary lesion is localized. The histologic features of papillary serous carcinoma resemble those of ovarian or tubal carcinoma. Cytologic atypia is so prominent that papillary serous carcinomas should always be graded as poorly differentiated tumors.

Another aggressive form of uterine carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, represents 5% to 10% of endometrial cancer cases and should also be considered a high-grade tumor. Clear cell carcinoma tends to occur in older women. Morphologically, it resembles clear cell carcinoma arising from other sites (eg, vagina, cervix, ovary), but clear cell carcinoma of the uterine corpus, unlike that of the vagina or cervix, is not associated with intrauterine exposure to diethylstilbestrol. The microscopic appearance varies and can include solid clear cell features, prominent glycogen content, and a glandular, tubulocystic, or papillary pattern. The cells have abundant clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm, sometimes containing periodic acid–Schiff-positive hyaline globules (Fig. 32-2). The nuclei show marked atypia with frequent mitotic figures. The characteristic “hobnail” appearance is seen as cells with scanty cytoplasm and nuclei protruding into the lumen of the gland. At least half of the clear cell carcinomas are admixed with uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC); this has contributed to ideas that the poor prognosis associated with clear cell carcinoma is due to the presence of UPSC.

As the name implies, mixed-cell endometrial cancers contain more than one type of tumor. The proportion of the minor component should exceed 10% for a tumor to be designated a mixed cell type.

Carcinosarcomas (also called mixed müllerian malignant tumors, MMMTs), consist of two components: malignant epithelial and mesenchymal tissue. In homologous MMMT, the sarcomatous component can be tissue that is normally found in the uterus; endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) or leiomyosarcoma are common. The so-called heterologous type of MMMT consists of tissue that does not normally appear in the uterus; rhabdomyosarcoma and chondrosarcoma are two common types (17,18,19). The MMMTs are believed to be aggressive carcinomas, rather than true sarcomas.

In 1988, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) committee established a surgical staging system for endometrial cancer (FIGO1988) (Table 32-2). In 2009, this staging system was updated to better stratify patients based on clinically relevant prognostic factors (FIGO 2009, Table 32-3).

| Stages | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| I | Tumor limited to uterus |

| IA | Confined to endometrium |

| IB | Invades ≤1/2 the myometrial deptha |

| IC | Invades >1/2 the myometrial deptha |

| II | Cervical extension |

| IIA | Involves endocervical gland only |

| IIB | Invades cervical stroma |

| III | Pelvic structures or intra-abdominal lymph node involvement |

| IIIA | Invades serosa or adnexa or is peritoneal cytology positive |

| IIIB | Vaginal metastasis |

| IIIC | Pelvic or para-aortic lymph node metastasis |

| IV | Other organ involvement |

| IVA | Invades bladder or rectal mucosa |

| IVB | Distant metastasis, including inguinal lymph node involvement |

| Stages | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Ia | Tumor confined to the corpus uteri |

| IAa | No or less than half myometrial invasion |

| IBa | Invasion equal to or more than one-half the myometrium |

| IIa | Tumor invades cervical stroma but does not extend beyond the uterusb |

| IIIa | Local and/or parametrial involvementc |

| IIIAa | Tumor invades serosa and/or adnexaec |

| IIIBa | Vaginal and/or parametrial involvementc |

| IIICa | Metastases to pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodesc |

| IIIC1a | Positive pelvic nodes |

| IIIC2 | Positive para-aortic lymph nodes with or without positive pelvic lymph nodes |

| IVa | Tumor invasion of bladder and/or bowel mucosa and/or distant metastases |

| IVAa | Tumor invasion of bladder and/or bowel mucosa |

| IVBa | Distant metastases, including intra-abdominal metastases and/or inguinal lymph nodes |

There are clinical and pathologic factors that can be used to predict the behavior of endometrial cancer. Clinical factors include age, ethnicity, and stage of disease. Pathologic factors include histologic type, grade, depth of myometrial invasion, LVSI, and spread of tumor outside the uterine cavity, including the retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

Studies have shown that outcomes for women with endometrial cancer are more favorable among younger patients. A retrospective study showed that patients less than 45 years old were statistically more likely to have endometrioid histology, grade I tumors, and stage IA disease, while women over age 65 were significantly more likely to have papillary serous histology and grade 3 tumors. A subset analysis of patients greater than 75 years of age showed an increase in the percentage of patients with aggressive papillary serous histology, higher-grade (grade 3) disease, and advanced-stage disease compared to those less than 45 years old. Evaluation of patients with endometrioid tumors revealed a similar pattern of deeper myometrial invasion and higher tumor grade as age increased (20). Other studies have shown that the risks of locoregional relapse and death among patients older than 60 years were twice as high as the risks among those aged 60 years or younger (21).

Studies in the United States have demonstrated that white women are more likely to be diagnosed with endometrial cancer than black women. Interestingly, however, black women diagnosed with endometrial cancer are more likely to die of their disease. They tend to be diagnosed at a later stage, with higher-grade tumors, and are more likely to have papillary serous histology. However, after controlling for these factors as well as other comorbid factors, a higher disease-specific mortality rate among black women still exists (22).

With regard to histologic subtype, papillary serous carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma are associated with worse prognosis than endometrioid carcinoma. Increasing tumor grade is associated with increased myometrial invasion, pelvic and para-aortic node involvement, recurrence, and a poorer overall survival (23) (Table 32-4, Fig. 32-3).

FIGURE 32-3

Tumor grade and survival in endometrial cancer. Use of the two-tier grading system is favored because of less interobserver variability and similar outcome for patients with grade 1 or 2 tumors (n = 243). (Reproduced with permission from Scholten AN, Creutzberg CL, Noordijk EM, Smit VT. Longterm outcome in endometrial carcinoma favors a two- instead of a three-tiered grading system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2002;52:1067-1074.)

| Grade | Pathologic Features | Percentage of Patients With Each Depth of Myometrium Invasion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial Only | Superficial | Middle | Deep | ||

| 1 | 5% or less of nonsquamous solid area | 24 | 53 | 12 | 10 |

| 2 | 6%-50% of nonsquamous solid area | 11 | 45 | 24 | 20 |

| 3 | >50% of nonsquamous solid area | 7 | 35 | 16 | 42 |

Lymphovascular space invasion, an independent risk factor for recurrence, is present in about 15% of endometrial cancer cases. Multivariate analyses have shown angioinvasion to be associated with survival in endometrial cancer regardless of disease stage. Independent of tumor grade or depth of myometrial invasion, LVSI is also associated with risk of pelvic and para-aortic node involvement and thus should lead to surgical nodal assessment or empiric radiation in patients with unstaged disease (23).

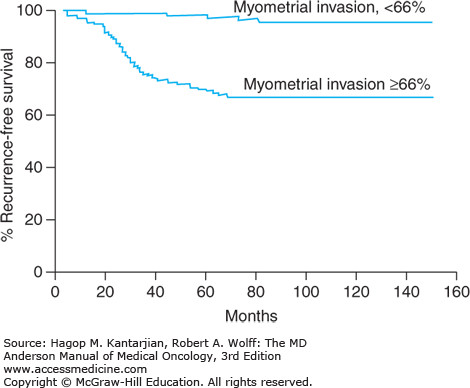

The depth of myometrial invasion is associated with degree of tumor differentiation, LVSI, lymph node involvement, extrauterine spread, recurrence, and overall survival (Fig. 32-4, Table 32-5). Adnexal metastasis correlates strongly with metastatic involvement of pelvic and para-aortic nodes; in one study, 32% of patients with adnexal involvement had positive pelvic nodes, as compared with 8% of those without adnexal disease (23). However, the alternative possibility of simultaneous ovarian and endometrial primaries must be ruled out as the surgical management and prognosis are vastly different. Up to 11% of patients with clinical stage I or II disease have lymph node involvement (23). The risk of para-aortic node involvement increases if the pelvic nodes are positive for tumor.

FIGURE 32-4

Recurrence-free survival rates for 282 patients with stage I endometrial cancer were significantly reduced when the depth of myometrial invasion exceeded two-thirds of the total thickness of the myometrium (P < .001). (Reproduced with permission from Mariani A, Webb MJ, Keeney GL, et al. Surgical stage I endometrial cancer: predictors of distant failure and death. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;87:274-280.)

| Risk Factors | Percentage of Patients With Positive Pelvic Nodes | Percentage of Patients With Positive Para-aortic Nodes |

|---|---|---|

| Histology | ||

| Endometrioid carcinoma | 9 | 5 |

| Others | 9 | 18 |

| Tumor grade | ||

| Grade 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Grade 2 | 9 | 5 |

| Grade 3 | 18 | 11 |

| Depth of myometrial invasion | ||

| None | 1 | 1 |

| Superficial | 5 | 3 |

| Middle | 6 | 1 |

| Deep | 25 | 17 |

| Tumor site | ||

| Fundus | 8 | 4 |

| Isthmus or cervix | 16 | 14 |

| Lymphovascular space invasion | ||

| Absent | 7 | 9 |

| Present | 27 | 19 |

| Peritoneal cytologic findings | ||

| Negative | 7 | 4 |

| Positive | 25 | 19 |

| Extrauterine metastasis | ||

| Absent | 7 | 4 |

| Present | 51 | 23 |

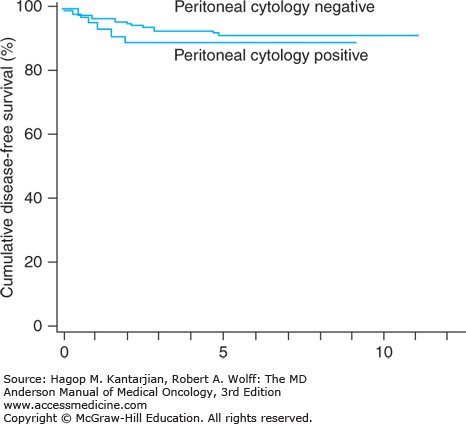

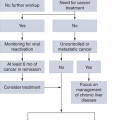

The current FIGO staging system does not incorporate peritoneal washings as the evidence for their prognostic value is weak. Positive findings on peritoneal cytology are often associated with other unfavorable prognostic factors, such as deep myometrial invasion, cervical extension, and extrauterine spread. In particular, UPSC demonstrates a high rate of positive washings. Even in clinical stage I disease that is confined to the uterus, cytologic findings have been positive in as many as 16% to 17% of cases (24). However, in at least two studies, the 5-year survival rates for patients with cytologically positive disease but no other risk factors have been higher than 90% (24) (Fig. 32-5).

FIGURE 32-5

Five-year survival rates for patients with endometrial cancer confined to the uterus with positive findings on peritoneal cytology (91%) were not different from those with cytonegative findings (95%) (n = 280). (Reproduced with permission from Kasamatsu T, Onda T, Katsumata N, et al. Prognostic significance of positive peritoneal cytology in endometrial carcinoma confined to the uterus. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:245-250.)

In conclusion, these prognostic factors correlate with clinical course of disease, recurrence, and risk of death. However, the relative importance of each factor is not always clear because of interrelations and interdependence among them. Results of a multivariate analysis by Zaino and colleagues of factors affecting survival in stages I and II endometrial cancer are summarized in Table 32-6 (25).

| Prognostic Factors | 5-Year Survival Rate (%) | Relative Risk of Surgical Stage I–II Tumorsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | ||

| Histologic cell type | ||||

| Clear cell | 67.7 | 5.1 | 3.5 | 2.5 |

| Mucinous | 100 | — | — | — |

| Serous | 55 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 4.4 |

| Endometrioid | 82.1 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| Endometrioid with squamous differentiation | 89.4 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Villoglandular | 91.2 | 0.01 | 0.5b | 41.9b |

| Myometrial invasion | ||||

| Endometrial only | 92.9 | 1 | ||

| Superficial | 87.6 | 0.5 | ||

| Middle | 84.5 | 3.3 | ||

| Deep | 62.6 | 4.6 | ||

| Lymphovascular space | ||||

| Invasion | ||||

| No | 85.8 | — | ||

| Yes | 60.9 | 1.4 | ||

| Grade | ||||

| 1 | 91.1 | — | ||

| 2 | 82 | — | ||

| 3 | 66.4 | — | ||

| Peritoneal washings | ||||

| Negative | 85.3 | — | ||

| Positive | 56 | — | ||

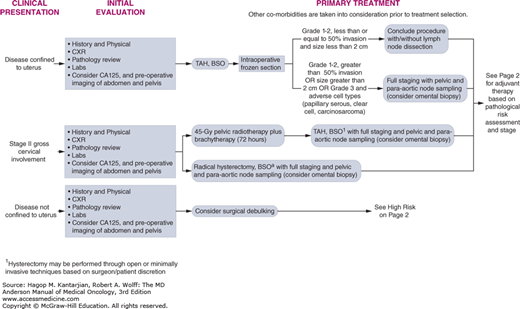

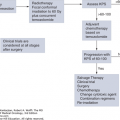

When evaluating a patient diagnosed with endometrial cancer, in addition to a history and physical examination, a chest x-ray should be performed, and imaging of the abdomen and pelvis should be considered. The measurement of cancer antigen 125 (CA125) may occasionally be useful (Fig. 32-6).

At MD Anderson, for patients with disease confined to the uterus, we recommend primary surgery with total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, except in cases with significant medical comorbidities (see Fig. 32-6). Lymph node evaluation is based on intraoperative evaluation of grade and depth of invasion. Patients with gross cervical involvement may either undergo radical hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, with full staging, including pelvic and para-aortic lymph node sampling, or they may undergo primary radiation therapy (see Fig. 32-6). For disease that is not confined to the uterus, surgical debulking is considered (see Fig. 32-6).

The standard staging procedure for endometrial cancer includes total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. However, the indications for performing a pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy for staging remain controversial among gynecologic oncologists. Some surgeons practice routine pelvic or pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy for all patients with endometrial cancer, whereas others perform these procedures only for those patients with an increased risk of lymph node metastases based on preoperative and intraoperative assessments. The decision to selectively perform lymph node staging is based on multiple concerns. First, many believe there has been insufficient or unconvincing evidence in the literature that routinely performing lymphadenectomy for all patients results in improved overall survival. Second, performing a lymphadenectomy is associated with additional risks for the patient, including the risk of additional surgical complications and the long-term development of lower extremity lymphedema. Finally, there is a very low rate of lymph node metastases in patients with early disease, specifically those with low-grade endometrioid adenocarcinoma with less than 50% invasion of the myometrium. The absence of LVSI and a tumor size of 2 cm or less in diameter also add reassurance that the lymph nodes are not involved (26)

Because of this, intraoperative gross inspection and frozen section of the uterus are commonly performed to evaluate the extent of uterine disease (see Fig. 32-6). This information may be used to further guide whether a lymph node dissection will be performed. The preoperative histologic findings and intraoperative pathologic findings that correlate with an increased risk of nodal involvement include grade 3 endometrioid histology; other aggressive histologies, including clear cell, serous, or squamous carcinoma; tumor invasion of more than half of the myometrium; tumor size greater than 2 cm; and the presence of extrauterine disease (23). In the presence of these variables, there is a benefit for surgical resection of the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes (see Fig. 32-6).

In the process of lymph node evaluation, mere palpation of the fatty tissue of node-bearing areas is inadequate for the evaluation of nodal status because only about half of metastatic nodes are enlarged, and fewer than 30% can be identified as abnormal on palpation (23). A representative lymph node sampling or lymph node dissection should be performed to adequately evaluate the nodal basins.

The use of sentinel lymph node biopsy to identify patients with lymph node metastases without performing a complete lymph node dissection is currently under study. Theoretically, this could be performed even in patients at low risk for metastases, thereby avoiding the additional risks associated with performing a lymphadenectomy while accurately identifying those in need of additional adjuvant therapy.

In two reports by the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG), laparoscopic surgical methods were compared to conventional laparotomy. The GOG LAP-2 study is the largest randomized trial ever performed in endometrial cancer. In this phase III prospective, multi-institutional, randomized study, 2,616 patients with stage I to IIA uterine cancer were assigned to laparoscopy (n = 1,696) or laparotomy (n = 920). Study end points were morbidity and mortality at 6 weeks, length of hospitalization, failure to complete laparoscopy, site of recurrence, and recurrence-free survival. Consistent with previous studies, laparoscopy required longer operative time but led to fewer postoperative adverse events and shorter hospitalization. The rate of intraoperative complications was similar. One unexpected outcome was that as many as 26% of patients in the laparoscopy arm were converted to laparotomy. Laparoscopic failure was associated with increasing age and body mass index (27).

In a companion report, patients undergoing surgical staging via laparoscopy versus laparotomy were assessed with quality-of-life (QOL) measures. The study’s objective was to compare the QOL of patients with endometrial cancer undergoing surgical staging via laparoscopy versus laparotomy. Although patients in the laparoscopy arm had overall better QOL measures at 6 weeks postsurgery, except for better body image in the laparoscopy arm, no difference was detected between the two arms at 6 months (28).

Robot-assisted surgery is a newer minimally invasive technique commonly offered to women with endometrial cancer. A recent systematic review included eight studies, with a total of 589 patients undergoing surgery for endometrial cancer. When robot-assisted surgery was compared to laparotomy, it was found to be associated with lower estimated blood loss at time of surgery, lower rates of wound complications, and lower rates of other postoperative complications (including stroke, ileus, nerve palsy, lymphedema). The duration of surgery was significantly longer in robot-assisted surgery compared to laparotomy (29).

The decision to perform open or minimally invasive surgery depends on patient preference, the skill and experience of the surgeon, the availability of the equipment, the size of the uterus, the parity of the patient, and the patient’s medical condition. At MD Anderson, minimally invasive approaches, both laparoscopic and robotic, are becoming the standard of care for the majority of women with endometrial cancer.

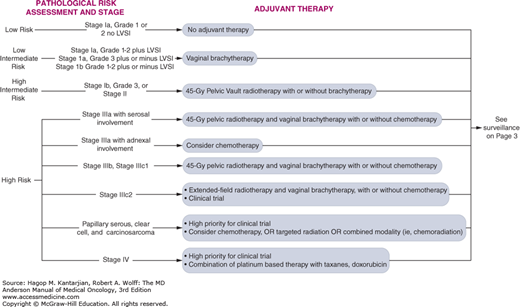

At MD Anderson, we stratify patients according to features of the disease and various prognostic factors (Fig. 32-7). The risk group helps guide the choice of adjuvant treatment. Women with grade 1 or 2 endometrioid tumors with no myometrial invasion or LVSI are considered to have low-risk disease. Low-risk disease is associated with an excellent prognosis, with 5-year survival approaching 90% and a low risk for recurrence after surgery. Therefore, in general, we do not recommend adjuvant therapy for this group of patients (see Fig. 32-7). Women with stage III disease, regardless of histology or grade, and women with serous carcinoma or clear cell carcinoma at any stage are considered to have high-risk disease and typically undergo adjuvant therapy. Intermediate-risk disease, therefore, includes women with endometrial cancer confined to the uterus that invades the myometrium or the cervix. The intermediate-risk group can be further stratified based on the presence of specific prognostic factors, including outer one-third myometrial invasion, grade 2 or 3 disease, and the presence of LVSI. Women are considered to have high-intermediate-risk disease if they are (1) any age with all three factors, (2) age 50 to 69 with two factors, and (3) age greater than or equal to 70 years old with one factor. For patients with intermediate-risk disease, there are ongoing controversies regarding the benefit of adjuvant therapy.

As mentioned, most patients with low-risk disease are unlikely to benefit from adjuvant therapy. Therefore, it is not generally recommended for this group (see Fig. 32-7).

A number of trials have addressed the question of adjuvant therapy in intermediate-risk endometrial cancers. At this time, there is no evidence that adjuvant therapy improves overall survival for women with intermediate risk disease. For intermediate-risk patients, adjuvant radiation therapy reduces the incidence of pelvic recurrence without prolonging overall survival (Fig. 32-8) (30

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree