EPIDEMIOLOGY

Cancer of the cervix is the third most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. In 2015, a total of 12,900 new cases of cervical cancer and 4,100 deaths are estimated (1). The incidence of this disease has decreased steadily over the past several decades. However, cervical cancer remains one of the most common cancers in women worldwide with approximately 527,600 new cases diagnosed each year and 265,700 related deaths (2).

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the cervix may occur at any age from the second decade of life onward. The mean age at diagnosis is approximately 51.4 years, with the number of cases evenly divided between patients at 30 to 39 and 60 to 69 years of age (3). Adenocarcinoma makes up to 15% to 25% of all invasive cervical cancers.

Risk factors for cervical cancer are listed in Table 33-1.

| Gynecologic Factor | Male Factor | Others |

|---|---|---|

| Human papillomavirus | History of penile cancer | Immunodeficiency |

| Number of sexual partners | Cervical cancer in ex-wife | Smoking |

| Age at first intercourse | Multiple sexual partners | Genetic predisposition |

| Multiparity | Nutrient deficiency | |

| Sexually transmitted disease | ||

| Oral contraception |

To understand the current methods for cervical screening, a basic understanding of the nature of cervical abnormalities is essential. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the critical factor for the development of preinvasive and invasive cervical lesions. More than 14 million incident cases are reported annually, the majority of which occur in persons age 15 to 24 years (4,5,6). HPV is a small, nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus predominantly transmitted through sexual intercourse. The most consistent risk factors for acquiring HPV are number of sexual partners, age of first sexual intercourse, and a partner infected with HPV.

More than 40 genotypes of HPV infect the epithelial lining of the anogenital tract and other mucosal areas of the body (7). These subtypes are further classified into high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) and low-risk HPV (LR-HPV) depending on their oncogenic potential for cervical cancer and its precursors. Low-risk HPV genotypes include HPV-6 and -11 and typically cause benign anogenital warts, although they may occasionally be associated with neoplastic cervical changes (8). Invasive lesions, on the other hand, are much more commonly caused by HR-HPV including, in order of frequency, types 16, 18, 31, 45, 52, and 33 (9). Although the majority of premalignant and invasive disease can be directly attributed to types 16 or 18, HPV DNA from any genotype is detectable in greater than 99% of all cervical cancer specimens (8).

Many studies have reported an increased risk of HPV infection and preinvasive and invasive cervical cancer in women who have low immunity, such as those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (10). It was found that rare HR-HPV types are more common in cervical dysplasia of HIV-infected women. It is possible that these other HPV types (35, 45, 52, and 59) are not able to evade the immune system as efficiently as HPV types 16 and 18, except in HIV-infected individuals who are immunocompromised (11).

The number of sexual partners is an important risk factor for both preinvasive and invasive cervical cancer. Many studies have found an increased relative risk of cervical cancer in women who have had more than six sexual partners (12). This is related to a higher risk of acquiring HPV infection.

Women who have intercourse early in life (<16 years of age) are more prone to develop cervical cancer (13). This increase in risk has been proposed because the process of transformation of columnar epithelium to squamous epithelium is active and is vulnerable to carcinogenic agents during early adolescence. However, these women frequently have other associated risk factors, such as multiple sexual partners and HPV infection.

Many studies have produced controversial results on the effect of oral contraception on cervical cancer risk. The relative risk of cervical cancer is increased in current users of oral contraceptives and declines after use ceases (14).

Tobacco use is a well-established risk factor for cancer of the cervix. Cigarette smoking confers a 1.5- to 2.5-fold increase in cancers of the cervix. Overall, tobacco smoking is estimated to account for 21% of cancer deaths worldwide, of which 2% (2% in high-income countries and 11% in low- and middle-income countries) are due to cervical cancer. Therefore, it is the most preventable risk factor for smoking-related cancer deaths (15).

Women with cervical cancer frequently report a history of having a male partner who has multiple other female partners, a history of condyloma infection, a history of intercourse with prostitutes, or an ex-wife or former partner with cervical cancer (12).

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Cervical SCCs are believed to develop from precursor or preinvasive lesions, which have been classified in a variety of ways but are generally based on the degree of disruption of epithelial differentiation. The oldest such system is the dysplasia–carcinoma in situ (CIS) system, with mild dysplasia at one end and severe dysplasia/CIS at the other. Another is the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) classification, with mild dysplasia termed CIN1 and CIS termed CIN3. The Bethesda System for reporting cervical/vaginal cytologic abnormalities categorizes squamous abnormalities as follows: low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), encompassing HPV infection and CIN1; high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion HSIL, encompassing CIN2 and CIN3; and SCC. These systems are compared in Table 33-2 (16).

| Comparison of Classification Systems | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HPV Risk Category | Dysplasia/CIN | Pap System | Bethesda System |

| — | Normal | Class I | Normal |

| Low risk | Inflammation | Class II | LSIL |

| Low risk | Inflammation | Class II | LSIL |

| Low and high risk | Inflammation | Class II | LSIL |

| Low and high risk | Mild dysplasia/CIN1 | Class III | LSIL |

| High risk | Moderate dysplasia/CIN2 | Class III | HSIL |

| High risk | Severe dysplasia/CIS/CIN3 | Class IV | HSIL |

| Cancer | Class V | ||

Microinvasion has been defined variably depending on the recommendations of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) (“preclinical invasive carcinoma diagnosed microscopically only”; depth of lesion, ≤5 mm; width, ≤7 mm) or Society of Gynecologic Oncology (depth of invasion, ≤3 mm with no lymphovascular space invasion [LVSI] or confluent pattern) (17). The depth of stromal invasion is measured from the base of the epithelium, either squamous or glandular, to the deepest point of invasion. Microinvasion can be diagnosed only with a conization specimen containing the entire lesion, having uninvolved margins, and having a sufficient number of sections examined by the pathologist.

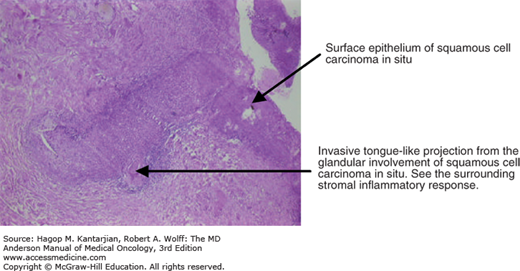

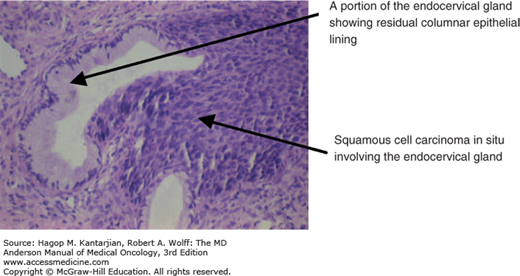

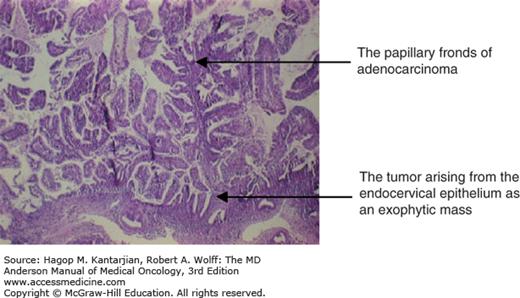

The histology of invasive foci is usually better differentiated than that of the nearby squamous intraepithelial lesion (Figs. 33-1 and 33-2).

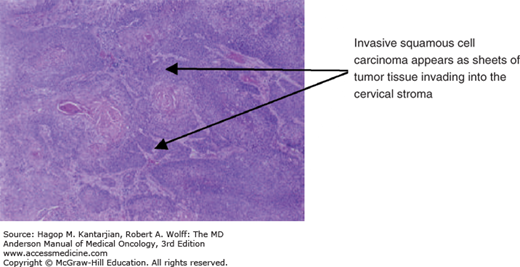

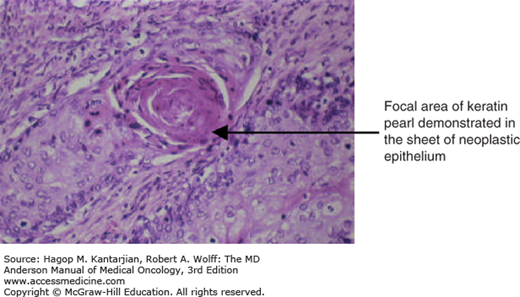

The histopathology of SCC is shown in Figs. 33-3 and 33-4.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified cervical adenocarcinoma into eight categories: (1) adenocarcinoma in situ, (2) early invasive adenocarcinoma, (3) adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified, (4) mucinous adenocarcinoma (including endocervical, intestinal, minimal deviation adenocarcinoma or adenoma malignum, signet ring cell, and villoglandular adenocarcinoma), (5) endometrioid adenocarcinoma, (6) clear cell adenocarcinoma, (7) serous adenocarcinoma, and (8) mesonephric adenocarcinoma.

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) is an intraepithelial glandular neoplasm that occurs in women at a younger age than invasive adenocarcinoma (18). Adenocarcinoma in situ is typically located at the transformation zone, although it may be present high up in the endocervical canal (between 20 and 30 mm, measured from the maximum convexity of the portio vaginalis). The principal morphologic features are cytologic malignant glandular epithelium with stratification, atypia, mitotic activity, and frequent apoptosis without stromal invasion. The cellular changes may be found focally in the glands and may have features of endocervical, endometrial, intestinal, or mixed cell types. The distinction between AIS and nonneoplastic glandular epithelium may at times be difficult; some authors have coined terms such as glandular dysplasia and glandular atypia for these lesser changes.

Although the concept of microinvasive adenocarcinoma has not been universally accepted, published literature suggests that patients with LVSI-negative cervical adenocarcinoma with depth of stromal invasion of <5 mm and a tumor volume of <500 μL can be treated with nonradical management (extrafascial hysterectomy with excision of the anterior leaf of the vesicouterine ligament, without lymph node dissection and oophorectomy) (19).

Various subtypes of adenocarcinoma have been noted due to their differentiation, as their respective names imply, such as mucinous adenocarcinoma, which can have endocervical or intestinal goblet cell features and the appearance of endometrioid, clear cell, serous, or mesonephric types. Adenoma malignum is usually an extremely benign-appearing cancer that is often diagnosed late and thus has a clinically poor prognosis. Clear cell adenocarcinomas may or may not be associated with diethylstilbestrol exposure in utero, but they have no known association with HPV (20). Serous adenocarcinoma is rare, with histology identical to its ovarian counterpart, and it carries a similarly bad prognosis. Mesonephric carcinomas are rare and are found in embryonal remnants of wolffian ducts, such as the uterine cervix, broad ligament, mesosalpinx, and exceptionally in the uterine corpus. The primary histologic pattern is tubular glands that vary in size and are lined by one to several layers of columnar cells (21) (Fig. 33-5).

SCREENING

Guidelines for screening have been put forth by American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (22) and are summarized below:

Cervical cancer screening should begin at age 21 years. Women younger than age 21 years should not be screened regardless of the age of sexual initiation or the presence of other behavior-related risk factors.

Women age 21 to 29 years should be tested with cervical cytology alone, and screening should be performed every 3 years. Human papillomavirus testing should not be performed in women younger than 30 years.

For women age 30 to 65 years, co-testing with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years is preferred.

In women age 30 to 65 years, screening with cytology alone every 3 years is acceptable. Annual screening should not be performed.

Women who have a history of cervical cancer, have HIV infection, are immunocompromised, or were exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero should not follow routine screening guidelines.

Both liquid-based and conventional methods of cervical cytology collection are acceptable for screening.

In women who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix (total hysterectomy) and have never had CIN2 or higher, routine cytology screening and HPV testing should be discontinued and not restarted for any reason.

Screening by any modality should be discontinued after age 65 years in women with evidence of adequate negative prior screening results and no history of CIN2 or higher. Adequate negative prior screening results are defined as three consecutive negative cytology results or two consecutive negative co-test results within the previous 10 years, with the most recent test performed within the past 5 years.

Since the Pap smear was initially developed, there have been several changes in nomenclature and interpretation to make the results more clinically relevant. At present, the Bethesda System is being used worldwide for cytologic diagnosis (see Table 33-2).

The Bethesda System is another procedure used for the cytologic diagnosis of cervical cancer. It was developed in 1988 and last updated in 2001 and is now used widely (23). The Bethesda System report is divided into three sections:

Specimen adequacy

Satisfactory for evaluation

Unsatisfactory for evaluation

General categorization (optional)

Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy

Epithelial cell abnormality

Other

Interpretation/result

Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy

Organism

Other nonneoplastic findings (optional to report; list not comprehensive)

Reactive cellular changes associated with (descriptive findings)

Glandular cells status post hysterectomy

Atrophy

Epithelial cell abnormalities

Squamous cell

Atypical squamous cells (ASCs); ASC of undetermined significance (ASC-US) and ASC cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H)

LSIL

HSIL

Glandular cell (specify endocervical, endometrial, or not otherwise specified)

Atypical glandular cells (AGCs)

AGCs, favor neoplastic

Endocervical AIS

Adenocarcinoma

Other (list not comprehensive)

Endometrial cells in a woman ≥40 years of age

Automated review and ancillary testing (include as appropriate)

Educational notes and suggestions (optional)

Note the following:

ASC: Some cells were seen that cannot be called normal but do not meet the requirements to call them precancerous. The abnormal cells may be caused by an infection, irritation, or intercourse or may be precancerous.

ASC-US

ASC-H

Squamous intraepithelial lesion: Changes were seen in the cells that may show precancerous signs. Squamous intraepithelial lesion can be low or high grade.

LSIL: Early, mild changes in the size or shape of cells were seen.

HSIL: Moderate or severe cell changes are seen; HSIL changes on a Pap smear suggest an increased risk of “precancer” when compared with LSIL changes.

AGC: Cell changes were seen that represent an abnormality that must be evaluated more closely. The type of evaluation depends on patient age and other factors.

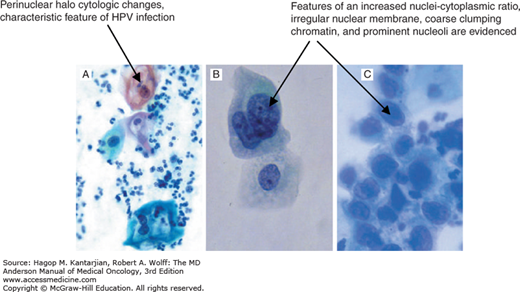

Example of cytologic features of HPV and CIN are shown in Fig. 33-6.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of growth of a cervical lesion is believed to progress through a state of microscopic invasion into the stroma and radial growth on the surface. Ultimately, a mass is formed, which, in general, grows locally to invade first the deeper stroma and later the paracervical and parametrial tissues. If left untreated, the disease will expand through these tissues to involve the lateral pelvic side wall and nearby viscera, such as the urinary bladder and rectum. Cancer arising from the cervix has been reported to involve the uterine corpus in 10% to 30% of cases. The incidence of ovarian metastasis in patients with cervical cancer is estimated at 0.22% for stage IB, 0.75% for stage IIA, and 2.2% for stage IIB with SCC, and 3.7%, 5.3%, and 9.9%, respectively, in adenocarcinoma (24).

A retrospective review of 360 patients with carcinoma of the cervix with clinical stage IB and IIA who had undergone radical hysterectomy and pelvic node dissection showed that lymph node metastasis was present in 21.9% of patients. In patients with and without lymph node metastasis, lymphovascular space invasion positivity, full-thickness stromal invasion, involvement of the uterine isthmus, positive parametrium, positive vaginal margins, and involvement of uterine corpus were seen in 25.3% and 9.2% (P < .001), 63% and 32% (P < .001), 32.9% and 13.8% (P < .001), 15.2% and 5% (P < .004), 24% and 14.2% (P < .005), and 17.7% and 13.8% (P = .11) of patients, respectively. In patients with lymph node metastases, 79.7% had grade 3 tumor compared with 69.5% of patients without lymph node metastases (P = .19). Multiple logistic regression indicated that only LVSI and full-thickness stromal invasion were statistically significant (P < .001 and P < .002, respectively) for lymph node metastasis (25). Distant metastasis to bones, lungs, breast, brain, and abdominal viscera often has a late presentation. Variant cell types, such as neuroendocrine and glassy cell carcinoma, may be associated with distant disease in the absence of local involvement.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical signs and symptoms of patients with cervical cancer vary depending on the stage and characteristic features of their lesions. Patients with early-stage disease may not have any abnormal symptoms; rather, their lesions may be discovered incidentally on a Pap smear. In patients with gross lesions, the most common presenting symptom is vaginal bleeding, which may have a characteristic pattern of mucous bloody discharge, postcoital bleeding, and/or intermenstrual, intermittent, or continuous vaginal bloody discharge. Vaginal bleeding is often found with exophytic cervical lesions. Tumor necrosis with superimposed infection may cause a mucopurulent bloody discharge with a foul smell due to anaerobic organisms. The symptoms in patients with more advanced disease include leg swelling due to compression of the venous or lymphatic system, pain due to nerve or bone involvement, and other urinary or bowel symptoms due to cancer invasion, such as hematuria or hematochezia.

INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF GYNECOLOGY AND OBSTETRICS STAGING

Cervical cancer is currently staged clinically using the FIGO system (17). Routine evaluation includes physical examination, pelvic and rectal examination, and pathologic review of cervical or cone biopsy specimens. Basic imaging studies such as chest x-ray, intravenous pyelography, cystoscopy, and proctoscopy are allowed in order to classify the disease into four stages, as shown in Table 33-3.

| Stage I | The carcinoma is strictly confined to the cervix (extension to the uterine corpus should be disregarded). |

| Stage IA | Invasive cancer identified only microscopically. (All gross lesions even with superficial invasion are Stage IB cancers.) Invasion is limited to measured stromal invasion with a maximum depth of 5 mma and no wider than 7 mm. |

| Stage IA1 | Measured invasion of stroma ≤3 mm in depth and ≤7 mm in width. |

| Stage IA2 | Measured invasion of stroma >3 mm and <5 mm in depth and ≤7 mm in width. |

| Stage IB | Clinical lesions confined to the cervix, or preclinical lesions greater than stage IA. |

| Stage IB1 | Clinical lesions no greater than 4 cm in size. |

| Stage IB2 | Clinical lesions >4 cm in size. |

| Stage II | The carcinoma extends beyond the uterus, but has not extended onto the pelvic wall or to the lower third of vagina. |

| Stage IIA | Involvement of up to the upper 2/3 of the vagina. No obvious parametrial involvement. |

| Stage IIA1 | Clinically visible lesion ≤4 cm |

| Stage IIA2 | Clinically visible lesion >4 cm |

| Stage IIB | Obvious parametrial involvement but not onto the pelvic sidewall. |

| Stage III | The carcinoma has extended onto the pelvic sidewall. On rectal examination, there is no cancer-free space between the tumor and pelvic sidewall. The tumor involves the lower third of the vagina. All cases of hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney should be included unless they are known to be due to other causes. |

| Stage IIIA | Involvement of the lower vagina but no extension onto pelvic sidewall. |

| Stage IIIB | Extension onto the pelvic sidewall, or hydronephrosis/nonfunctioning kidney. |

| Stage IV | The carcinoma has extended beyond the true pelvis or has clinically involved the mucosa of the bladder and/or rectum. |

| Stage IVA | Spread to adjacent pelvic organs. |

| Stage IVB | Spread to distant organs. |