Tumors of the penis and the urethra

James F. Holland, MD, ScD (hc)  Raymond S. Lance, MD

Raymond S. Lance, MD  Donald F. Lynch, Jr. MD

Donald F. Lynch, Jr. MD

Overview

Carcinoma of the penis, predominantly squamous, some related to human papilloma virus, is rare in the developed world and among circumcised men, but of major importance elsewhere. Surgery early can be curative. Other modalities are less robust. Voluntary adult circumcision to diminish susceptibility to human immunodeficiency virus infection is being observed as possibly preventive. Urethral cancer, rare, usually of transitional epithelium, is often detected too late for cure.

Squamous carcinoma of the penis is a largely preventable disease, dependent on early circumcision, personal hygiene, access to healthcare, and avoidance of human papilloma virus (HPV). Because the disease is rare in the developed world, the efficacy of HPV immunization will likely be determined in the developing world. Early recognition of tumor lesions correlates with lower staging and more effective treatment with better organ sparing and lower mortality.

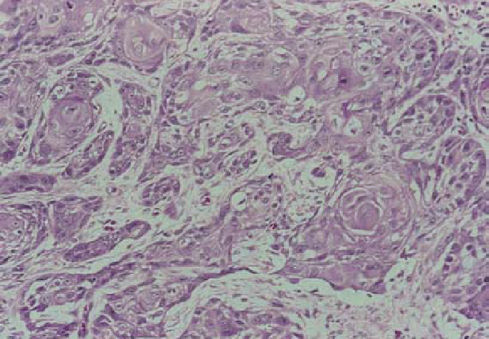

Cancer of the penis is an unusual disease in the United States (<2000/year) and Europe, but is a major health problem in Africa, Asia, and South America. Approximately 95% of primary penile cancers are squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) (Figure 1). Other cancers involving the penis are verrucous carcinoma, alternatively known as giant condyloma or Buschke-Lowenstein tumor, a variant of squamous carcinoma which does not metastasize, but which spreads aggressively by local extension and destroys surrounding tissue (Figure 2).1 Epidemic Kaposi’s sarcoma associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is now uncommon (Figure 3). Melanoma and basal cell carcinoma very rarely involve the penis. A scaly red clearly demarked intraepithelial squamous carcinoma in situ (CIS) is denominated Bowen’s disease when it involves the base of the penis and the scrotum. When CIS involves the glans or prepuce, it appears as shiny red velvet and is known as erythroplasia of Queyrat (Figure 4). Carcinomas in situ have the potential to develop into invasive squamous carcinoma in about 20%. Biopsy is required to establish a diagnosis. Leukemias and lymphomas can present as priapism. Diagnosis and therapy for them are systemic.

Figure 1 Microscopic squamous cell carcinoma, moderately well differentiated, with characteristic keratin pearl formation.

Figure 2 Verrucous carcinoma (Buschke-Lowenstein tumor).

Figure 3 Lesion of epidemic (AIDS-related) Kaposi sarcoma involving glans. Courtesy of Dr. Victor Marcial.

Figure 4 Erythroplasia of Queyrat of glans.

Epidemiology and etiology

In countries where infant circumcision is common, such as Israel and the United States, the incidence of squamous carcinoma of the penis is low. Circumcision later in life has not conferred protection, perhaps because it was done for cause such as phimosis and balanitis.2 Proper hygiene is made difficult by phimosis, perpetuating chronic inflammation of the glans penis and preputial tissue. Inexpensive adult circumcision as a protective measure against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, recently practiced in Africa, may alter this information.2

An association between cervical cancer in women whose partners have penile cancer has been observed, and squamous carcinoma of the penis and of the cervix has been associated with human papilloma viruses (HPV [16,18,31]).3 The foreskin of 9% of uncircumcised preadolescent boys contained HPV, attesting to the ubiquity of this virus.4 Uncircumcised men are three times more likely to harbor HPV than circumcised men, and female partners of circumcised men are less likely to develop cervical cancer.5, 6 HPV shedding may occur in asymptomatic carriers, in those with unrecognized intraurethral lesions, or men with condyloma accuminata, exposing their partners of either sex. Tobacco smoking is correlated with increased HPV infection and cancer of the penis and cervix.5

Diagnosis

Early invasive tumors may be small and largely unremarkable, sometimes resembling small abrasions (hair cuts) or calloused thickenings of penile skin. The initial lesion of squamous carcinoma most commonly presents on the glans or prepuce. It varies from a small, velvety, reddened, raised maculopapule to an ulcer, hyperkeratotic area, or exophytic papillary tumor. Biopsy is required to make the diagnosis and should include contiguous normal skin for comparison.1 More advanced lesions may be exophytic or ulcerated, and very advanced cancers may completely destroy the penile shaft. Metastases to the inguinal lymph nodes may produce large ulcerations in the groin late in the course of the disease. Well-differentiated tumors tend to metastasize infrequently, while more poorly differentiated tumors have a high propensity for early metastasis. Several studies have confirmed that higher tumor grade increases the likelihood of inguinal nodal metastases.7

Metastasis

Invasive squamous carcinoma of the penis follows a predictable pattern of metastasis. Lesions of the glans, coronal sulcus, prepuce, and distal shaft spread to the deep inguinal nodes, while lesions of the proximal shaft and base of the penis spread to the more lateral and superficial inguinal nodes. Subsequent spread to the external iliac, obturator, and iliac chains follows.8 Metastases to distant sites are infrequent and occur late in the course of disease. Left untreated, penile cancer progresses, causing the deaths of the majority of those untreated within 3 years.

Because primary lesions may be infected or chronically inflamed, secondary inflammation of the inguinal nodes is often present which may be difficult to distinguish from metastatic disease. Careful re-examination of the inguinal nodes following a 4–6-week course of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy may help to differentiate inflammation from cancer.

Tumor staging

Once the diagnosis of squamous carcinoma is established, complete staging is undertaken. Inguinal nodes are carefully palpated. Additional studies should include chest X-ray, computerized tomography (CT) of the pelvis and inguinal regions, and possibly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).9 Positron emission tomography-computerized tomography (PET-CT) and MRI are superior to palpation for detection of suspicious nodal enlargement. Lymph angiography is no longer used as a staging procedure. MRI provides good discrimination of penile structures and may identify corpora cavernosal or spongiosal invasion.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumor, Nodes, Metastases (TNM) system, seventh edition, is the accepted staging system for penile cancer (Table 1).

Table 1 AJCC (2010) TNM staging of penile cancer

| Primary tumor (T) | |||

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | ||

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | ||

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ | ||

| Ta | Noninvasive verrucous carcinomaa | ||

| T1a | Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue without lymph vascular invasion and is not poorly differentiated (i.e., grades 3–4) | ||

| T1b | Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue with lymph vascular invasion or is poorly differentiated | ||

| T2 | Tumor invades corpus spongiosum or cavernosum | ||

| T3 | Tumor invades urethra | ||

| T4 | Tumor invades other adjacent structures | ||

| Regional lymph nodes (N) | |||

| Clinical stage definitiona | |||

| cNX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | ||

| cN0 | No palpable or visibly enlarged inguinal lymph nodes | ||

| cN1 | Palpable mobile unilateral inguinal lymph node | ||

| cN2 | Palpable mobile multiple or bilateral inguinal lymph nodes | ||

| cN3 | Palpable fixed inguinal nodal mass or pelvic lymphadenopathy unilateral or bilateral | ||

| Anatomic stage/prognostic groups | |||

| Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| Ta | N0 | M0 | |

| Stage I | T1a | N0 | M0 |

| Stage II | T1b | N0 | M0 |

| T2 | N0 | M0 | |

| T3 | N0 | M0 | |

| Stage IIIa | T1–3 | N1 | M0 |

| Stage IIIb | T1–3 | N2 | M0 |

| Stage IV | T4 | Any N | M0 |

| Any T | N3 | M0 | |

| Any T | Any N | M1 | |

| ICD-O-3 topography codes | |||

| C60.0 | Prepuce | ||

| C60.1 | Glans penis | ||

| C60.2 | Body of penis | ||

| C60.8 | Overlapping lesion of penis | ||

| C60.9 | Penis, NOS | ||

a Clinical stage definition based on palpation, imaging.

Source: Edge et al.10 Reproduced with permission of Springer.

Surgical treatment

Treatment of penile cancer is based on the extent of the primary tumor and its tumor grade, established by biopsy of the lesion. Antibiotic therapy is begun before biopsy and continued throughout surgical treatment and from 4 to 6 weeks afterward. Lymph node metastasis is assessed. Once the tissue diagnosis is confirmed, small superficial tumors may be treated successfully with local surgical excision, LASER surgery,11 Mohs’ micrographic surgery,12 or superficial radiation therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree