Tumors of the heart and great vessels

Anthony F. Yu, MD  Sai-Ching Jim Yeung, MD, PhD, FACP

Sai-Ching Jim Yeung, MD, PhD, FACP  Carmen P. Escalante, MD

Carmen P. Escalante, MD  Sarina van der Zee, MD

Sarina van der Zee, MD  A. P. Chahinian, MD

A. P. Chahinian, MD  Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD

Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD

Overview

Primary tumors of the heart and great vessels are rare, but secondary tumors are significantly more common. Clinical manifestations of cardiac tumors depend on the location and size of the mass, not on the histopathology of the tumor. Several noninvasive imaging modalities including echocardiography, cardiac MRI, cardiac CT, and PET are currently available to provide complementary information on the location, extent, and tissue characteristics of a cardiac tumor. The clinical management of patients with cardiac tumors varies based on the type of tumor, clinical symptoms, and overall prognosis.

Introduction

Primary cardiac tumors are extremely rare, with a prevalence of <0.1% to 0.3% based on autopsy series.1–4 More than 75% of primary cardiac tumors are benign (Table 1).5, 6 The majority of malignant primary cardiac tumors are sarcomas and lymphomas, which carry a poor prognosis despite treatment.7, 8 In contrast to primary cardiac tumors, metastases to the heart are relatively common.2, 9–11 While most primary tumors arise from the endocardium, followed by the myocardium and then the pericardium,2 the latter is the most common site for metastases.12

Table 1 Type and frequency of primary tumors of the heart and pericardium in two series from the armed forces institute of pathology

| 1976–1993 series | Pre-1977 series | |||

| Type | n | % | n | % |

| Benign tumors | ||||

| Myxoma | 114 | 27.9 | 130 | 29.3 |

| Papillary fibroelastoma | 31 | 7.6 | 42 | 9.5 |

| Rhabdomyoma | 20 | 4.9 | 36 | 8.1 |

| Lipoma | 2 | 0.5 | 45 | 10.1 |

| Fibroma | 20 | 4.9 | 17 | 3.8 |

| Hemangioma | 17 | 4.2 | 15 | 3.4 |

| Atrioventricular nodal tumor | 10 | 2.4 | 12 | 2.7 |

| Teratoma | 4 | 1.0 | 14 | 3.2 |

| Lipomatous hypertrophy, atrial septum | 12 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Granular cell tumor | 4 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.7 |

| Lymphangioma | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Benign fibrous tumor | 3 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Neurofibroma | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.7 |

| Histiocytoid cardiomyopathy | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Inflammatory pseudotumor | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Myocytic hamartoma | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Paraganglioma | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 248 | 60.6 | 319 | 71.8 |

| Malignant tumors | ||||

| Angiosarcoma | 37 | 9.0 | 39 | 8.8 |

| Unclassified sarcoma | 35 | 8.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 6 | 1.5 | 26 | 5.9 |

| Mesothelioma | 8 | 2.0 | 19 | 4.3 |

| Fibrosarcoma | 9 | 2.2 | 14 | 3.2 |

| Osteosarcoma | 13 | 3.2 | 5 | 1.1 |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | 16 | 3.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Lymphoma | 7 | 1.7 | 7 | 1.6 |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 12 | 2.9 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Myxosarcoma | 8 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Synovial sarcoma | 5 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Malignant teratoma | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.9 |

| Neurogenic sarcoma | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.9 |

| Thymomaa | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.9 |

| Liposarcoma | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Malignant schwannoma | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Yolk sac tumor | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 161 | 39.4 | 125 | 28.2 |

| Total tumors | 409 | 444 | ||

a From thymic rests in the parietal pericardium.

Source: Adapted from Refs. 4 and 5. Cysts are excluded.

Clinical features

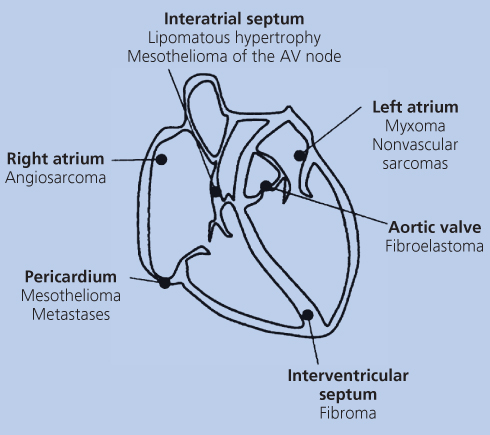

The clinical manifestations of cardiac tumors frequently reflect the cardiac structure involved, tumor size, and the friability of the tumor rather than its histology.12 The underlying mechanism responsible for clinical symptoms is varied and may include embolization, intracardiac or valvular obstruction, or direct invasion of myocardium or adjacent organs. The predominant site of common cardiac tumors is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Predominant sites of common cardiac tumors.

Tumors of the endocardial surface may present with valvular dysfunction or intracavitary obstruction. Right atrial tumors can lead to tricuspid valve obstruction and symptoms of right heart failure (i.e., fatigue, peripheral edema, ascites, hepatomegaly, jugular vein distention). Left atrial tumors tend to cause symptoms by obstructing blood flow and typically present with left heart failure symptoms (i.e., dyspnea, orthopnea, pulmonary edema, or hemoptysis). Myocardial invasion may present as arrhythmia, conduction abnormalities, systolic dysfunction, or diastolic dysfunction. Rarely, complete cavitary obstruction may lead to sudden death. Pericardial involvement can present as pleuritic chest pain or cardiac tamponade. Friable tumors, such as some myxomas and papillary fibroelastomas, may present with evidence of cerebral, pulmonary, visceral, or peripheral emboli. Systemic manifestations, frequently seen in myxomas as well as malignant cardiac tumors, include fever, weight loss, myalgias, arthralgias, fatigue, and weakness.

Patients with cardiac tumors may present with the symptoms described above, or masses may be discovered incidentally on imaging studies, particularly when small in size. Physical examination may disclose a murmur, either systolic or diastolic, that varies with body position if the tumor is mobile. The characteristic “tumor plop” of a mobile tumor such as a myxoma is heard in diastole following the second heart sound and is thought to be due to the tension on the tumor stalk as the mass prolapses from atrium to ventricle or to the tumor striking the myocardium.10 The tumor plop may be mistaken for a third heart sound or mitral opening snap. The electrocardiogram may show nonspecific ST-T abnormalities, atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, bundle branch block, or low voltage QRS complexes in the case of pericardial effusion. Chest X-ray findings include cardiomegaly and tumor calcification. Laboratory abnormalities include anemia (possibly hemolytic) or erythrocytosis, leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, increased serum immunoglobulin levels, and elevated acute-phase reactants such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein.10

Diagnostic evaluation

Several cardiac imaging techniques are available for evaluation of patients with suspected cardiac masses. Two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) provides excellent spatial and temporal resolution of cardiac masses and is often the initial imaging modality of choice.13 However, TTE can be limited by poor acoustic windows and lack of tissue characterization. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) allows for better tumor localization and characterization as well as assessment of intra- and extracardiac invasion. The use of contrast echocardiography may help to improve echocardiographic resolution and provide information on tumor vascularity.14 Real-time three-dimensional echocardiography can offer incremental value over two-dimensional echocardiography by providing an accurate assessment of size and shape of the mass and enabling better localization of attachment point.15

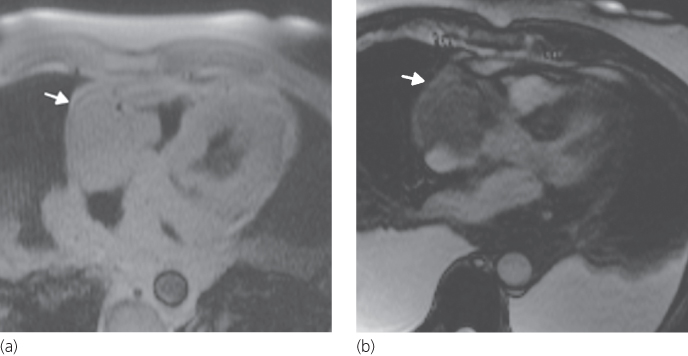

Cardiac computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide cross-sectional images of the heart with high temporal and spatial resolution. Both modalities are able to depict intra- and extracardiac masses, as well as degree of myocardial or pericardial involvement, without limitations owing to body habitus or poor acoustic windows. Cardiac CT provides limited information regarding tissue characterization, but disadvantages of cardiac CT include radiation exposure and potential nephrotoxicity of contrast agents.16 Cardiac MRI provides the highest degree of soft tissue contrast of any imaging modality and combines outstanding tumor localization, visualization of adjacent structures, and myocardial motion and perfusion assessment (Figure 2).17–19 In addition, tailored imaging sequences allow more specific characterization of particular tumors.18 Tissue characteristics of the cardiac mass can be evaluated using T1- and T2-weighted images, as well as enhancement with gadolinium contrast.20 Although the spatial resolution of CT is greater than MRI, the soft tissue characterization of CT is inferior to MRI and thus, CT can be considered an intermediate modality appropriate in select patients.16 Positron emission tomography (PET) can also help to identify cardiac involvement in patients with malignant tumors.21 Cardiac angiography, once a mainstay in the diagnosis of cardiac tumors, has fallen out of use given the risk of embolization during the procedure.

Figure 2 Cardiac MRI of a 69-year-old man with lymphoma demonstrating a large homogeneous mass (arrows) occupying most of the right atrium and extending into the right ventricle and posterior mediastinum. (a) Dark-blood image in the four-chamber view obtained using T2-weighted half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin echo. (b) Bright-blood image in the four-chamber view obtained using steady-state free precession; note the large bilateral pleural effusions.

When a cardiac mass is discovered on an imaging study, the differential diagnosis includes thrombus and vegetation, in addition to primary or secondary tumors.22, 23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree