30531

Treatment of Cancer Pain in the Elderly

Koshy Alexander and Paul Glare

INTRODUCTION

Pain is a common problem in older cancer patients, estimated to affect 80% of those with advanced disease (1). Although there is evidence for some age-related decline in pain sensitivity, older patients are more vulnerable to severe, persistent pain, and less tolerant of it (2). Pain in the elderly is often undertreated (3), which not only causes treatable discomfort but leads to the development of other symptoms that impair quality of life, such as depression, anxiety, isolation, sleep disturbances, loss of appetite, and impaired functional capacity (4). Identification and optimal management of pain thus become a priority in these patients.

The principles of cancer pain management in the elderly are similar to those used with younger patients, with opioids being the mainstay. However, age-related physiologic changes, comorbidities, and polypharmacy should be taken into account. Narcotic abuse in the elderly is an emerging problem (5).

CLASSIFICATION OF CANCER PAIN

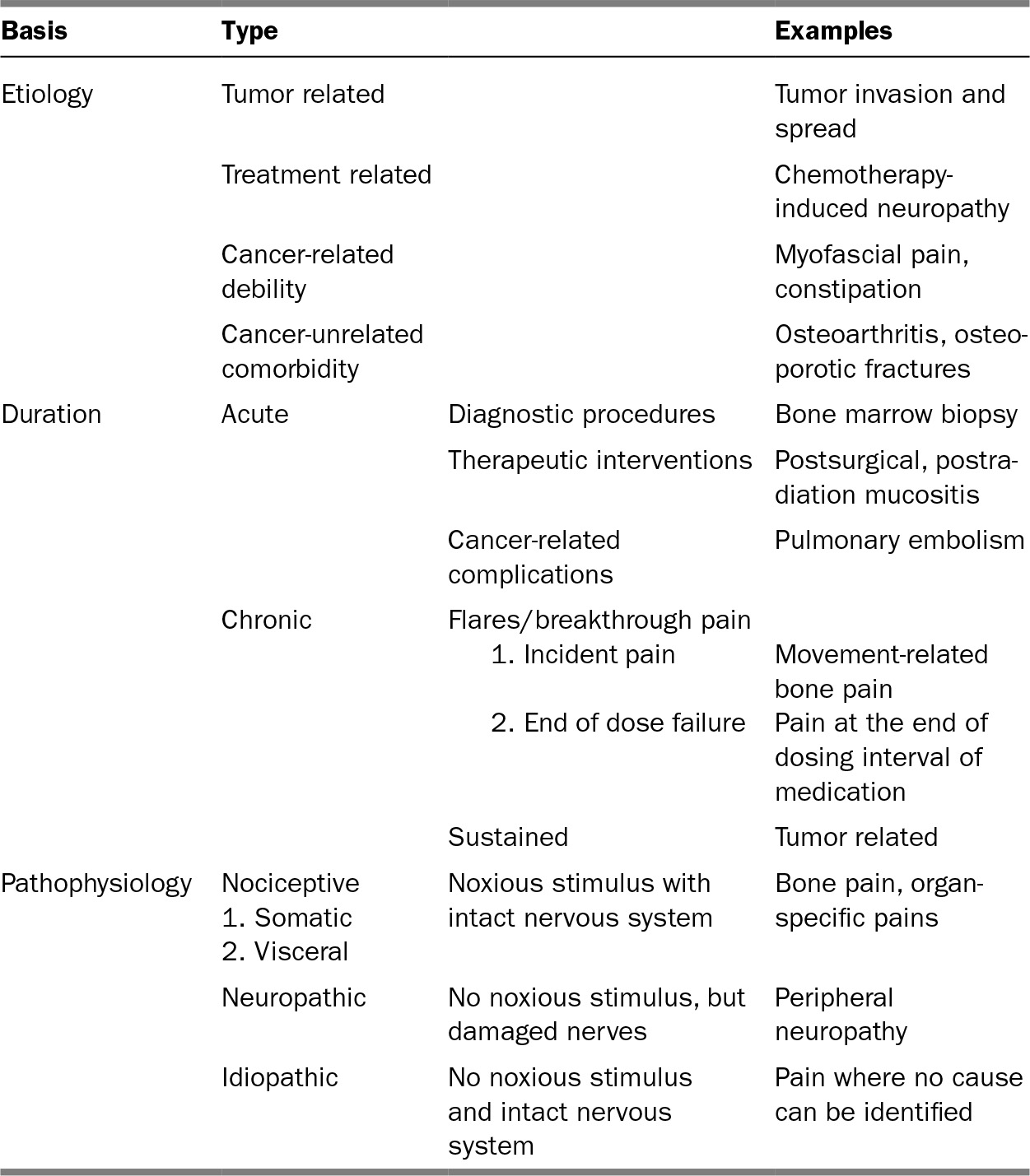

The prevalence of pain varies widely depending upon the type of cancer, from 85% in those with primary bone tumors to only 5% in those with leukemias (6). Cancer pain is not a uniform entity with a single effective treatment, and not all cancer pain is due to the tumor. There are several ways to classify cancer pain (Table 31.1). It is helpful to do so as this may direct the optimal treatment approach. Most cancer pain is chronic, but it can be acute. Unlike most chronic nonmalignant pain, chronic cancer pain worsens as disease progresses. It is also associated with pain flares called breakthrough pain (BTP). BTP is associated with both pain-related functional impairment and psychological distress (7).

ASSESSMENT

Optimal pain management in the elderly starts with the assessment. In addition to presence and intensity, characteristics such as quality, temporal features, and aggravating and alleviating factors help identify the etiology. An assessment of pain behaviors, pain-related morbidity, coping style, and response to prior treatments should be included (8). Social, cultural, and economic factors may play a key role in adherence to the pain management regimen charted out. Comprehensive evaluation includes a physical examination, review of imaging, and other data, with the objective of confirming the pain etiology suggested by the history, along with medication reconciliation.

306TABLE 31.1 Classification of Pain in Cancer

Cancer pain evaluation is challenging in older patients when there are concomitant comorbidities, cognitive impairment, frailty, or impaired communication (including mechanical ventilation) (9). Patients with mild to moderate dementia may still be able to report pain, but the ability to self-report pain decreases as dementia progresses (10). Observing specific pain behaviors is advocated in this situation (11). Pain scales should be used in the elderly (Table 31.2).

307MANAGEMENT

Cancer pain management shares features with the treatment of nonmalignant pain. Analgesic drugs form the cornerstone of cancer pain management. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) three-step analgesic ladder provides an algorithm for using analgesics, with the addition of adjuvant agents when there is a neuropathic component (Table 31.3). There is controversy about the need for the second step, as low doses of strong opioids work as well as weak opioids. In practice, many patients prefer to try weak opioids before escalating to strong opioids. Treatment plans should incorporate nonpharmacologic interventions. These aim to treat the affective, cognitive, behavioral, and sociocultural dimensions of cancer pain. Barriers to pain control include inadequate patient and physician education (3).

Pharmacologic Therapies

NONOPIOID ANALGESICS

Acetaminophen is preferred in older cancer patients, as they are at higher risk of the side effects associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Patients should be counseled not to consume more than 3,000 mg of acetaminophen per day due to potential liver toxicity. If NSAIDs are used, it should only be for short intervals (16), as NSAID-associated side effects (e.g., gastrointestinal bleeding, renal toxicity, myocardial infarction, and stroke) are dose and time dependent. A gastro-protective medication such as a proton pump inhibitor should be prescribed alongside (17). Cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective inhibitors may increase the risk of thrombotic cardiovascular adverse reactions and do not protect from renal failure. In essence, NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors can provoke severe toxicity reactions such as gastrointestinal bleeding, platelet dysfunction, and renal failure (18). Absolute contraindications to the use of NSAIDs include chronic kidney disease, active peptic ulcer disease, and heart failure.

TABLE 31.2 A Few Validated Pain Assessment Tools in the Elderly Population

Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate (PACSLAC) (12) |

Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) (13) |

Rotterdam Elderly Pain Observation Scale (REPOS) (14) |

Checklist of Nonverbal Pain Indicators (CNPI) (15) |

TABLE 31.3 WHO Analgesic Ladder

Step | Recommendations | Suggested Medications |

Step 1—mild pain | Nonopioid ± adjuvant | Acetaminophen, NSAIDs Gabapentin, pregabalin |

Step 2—moderate pain | Weak opioid ± nonopioid ± adjuvant | Hydrocodone, tramadol; buprenorphine patch Acetaminophen, NSAIDs Gabapentin, pregabalin |

Step 3—severe pain | Strong opioid ± nonopioid ± adjuvant | Morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl, methadone Acetaminophen, NSAIDs Gabapentin, pregabalin |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree