10713

Geriatric Assessment

Sincere McMillan and Beatriz Korc-Grodzicki

INTRODUCTION

A primary determination when considering appropriate therapy for an older patient with cancer is the patient’s functional age. The aging process itself brings physiologic changes leading to a decline in organ function. The remodeling of physiologic reserve is influenced not only by genetic factors, but also by environmental factors, dietary habits, and the interaction of comorbidities and social conditions. Therefore, chronological age differs from functional age, and this difference must be captured and integrated in the decision-making process of cancer treatment. It is essential to identify those patients who are fit and potentially more resilient, because they are more likely to benefit from standard treatment, as opposed to patients who are more frail and vulnerable to adverse outcomes. This chapter describes how to assess geriatric syndromes through a comprehensive geriatric assessment (GA) and the association of GA results with cancer-related outcomes.

GERIATRIC ASSESSMENT

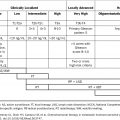

GA is a multidimensional, interdisciplinary evaluation. In older cancer patients, it is used to determine physiologic age, guide future diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, determine any reversible deficits, and devise treatment strategies to eliminate or mitigate such deficits and to risk-stratify patients prior to potentially high-risk therapy (1). Although there is no standard definition of a GA, a position paper by the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) provided clarification regarding necessary elements of GA and guidance to tools that could be used for each element (1). The domains of a GA are shown in Table 13.1 along with examples of validated tools to measure those domains.

Assessment of Comorbidities

The incidence of pathology increases as we age. The presence of multiple chronic diseases or comorbidities represents a major difference between the younger and the older cancer patient. Frequent comorbidities in the elderly, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, or dementia, influence the management of cancer. Comorbidities may increase the risk of complications, modify cancer behavior, or mask symptoms with subsequent delays in cancer diagnosis. Conversely, cancer treatment may worsen comorbidities or increase the frequency of drug interactions.

108TABLE 13.1 Domains in GA and Examples of Tools Used for Each Domain

Domain | Tool |

Social status and quality of life | Medical outcomes survey (2) |

Comorbidity | CCI (3) CIRS-G (4) |

Functional status | ADL (5) IADL (6) |

Physical function | TUG (7) Short physical performance battery (8) Gait speed (9) Grip strength (10) 6-min walk (11) |

Falls and falls risk | Tinetti Gait and Balance Scale (12) |

Cognition | MMSE (13) MoCA (14) The BOMC Test (15) Mini-Cog (16) |

Nutrition | BMI Unintentional weight loss MNA (17) |

Medication management and polypharmacy | Use of inappropriate medications (such as the Beers list or screening tool for older persons’ prescriptions) (18) Number of medications |

Psychological status | GDS (19) Hospitalized Anxiety and Depression Scale (20) PHQ-9 (21) DT (22) |

ADL, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; BOMC, blessed orientation-memory-concentration; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CIRS-G, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale–Geriatrics; DT, distress thermometer; GA, geriatric assessment; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MNA, Mini Nutritional Assessment; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PHQ-9, patient health questionnaire-9; TUG, Timed Up and Go.

Comorbidity burden is often measured using standardized indices such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (3) and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale–Geriatrics (CIRS-G) (4). The CCI is based on the 1-year mortality of patients admitted to a medical hospital service. It is a simple instrument with well-defined rating criteria that has been validated in older cancer patients. The CCI can be used for 109large cohort studies; however, it may underdetect nonlethal endpoints. The geriatric version of the CIRS-G was designed for use in elderly populations. Although it details several geriatric concerns, the scale may overdetect minor problems, and it is quite complicated to rate.

Cognitive Assessment

Cancer patients with cognitive dysfunction represent a new challenge for oncologists. After age 65, the risk of developing Alzheimer disease doubles approximately every 5 years. By age 85, 37% of all people will have some signs of the disease (23). The increased rate of dementia in the elderly converges with the higher likelihood of developing cancer. For patients with cancer/dementia, overlap screening tends to be less standardized, which could lead to delayed diagnosis. Impaired cognition can result in significant difficulties in understanding and remembering treatment instructions, delayed diagnosis of complications, and decreased adherence to oral therapies and supportive treatments. An initial assessment of cognitive status is clinically important and could influence the choice of treatment and the modality of administration (Table 13.2).

The ability of patients to decide on a course of therapy in concert with the oncologist is critically important. Many oncologists are conflicted as to whether true informed consent for treatment can be obtained from older cancer patients when their cognitive abilities are impaired or unclear. It is imperative that health care providers who care for older adults with cancer be able to assess cognitive function, understand the implications of cognitive impairment when patients need to make decisions, address the potential for treatment-related cognitive decline, and be able to facilitate patient-centered cancer decision making.

TABLE 13.2 Common Instruments Validated for Cognitive Screening

MMSE (13) | Widely used screening tool covering multiple domains such as orientation, memory, attention, calculation, language, and constructional ability. |

MoCA (14) | More sensitive test designed as a rapid screening instrument for mild cognitive dysfunction. It was found to provide additional information over the MMSE in brain tumor patients (24). |

BOMC (15) | Brief, six-item scale frequently used in the geriatric oncology literature. |

Mini-Cog assessment instrument (16) | Brief test that screens for cognitive impairment in a community sample of culturally, linguistically, and educationally heterogeneous older adults. It requires minimal training to administer, so it can be readily incorporated into general practice. |

BOMC, blessed orientation-memory-concentration; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

Medication Management and Polypharmacy

110Pharmacotherapy in the elderly is often very complex due to age-related physiologic changes, multiple comorbidities, and multiple medications. In addition, cognitive impairment, functional limitations, and caregiver issues play a large role in adherence to medication regimens. Age-related physiologic changes and disease-related changes in organ function affect drug handling (pharmacokinetics) and response (pharmacodynamics), both of which significantly impact prescribing. Older cancer patients usually take multiple medications, not only for treatment of the cancer, but also for supportive care and the management of symptoms related to therapy-induced toxicity (25). Further discussion on medication management appears in Chapter 8.

Social Issues and Quality of Life

Social support has a substantial impact on cancer and cancer treatment outcomes. Evidence in breast cancer patients suggests that low social support is associated with development and progression of cancer (26). Once diagnosed, cancer has a substantial impact on quality of life and on social function at any age. Older patients with cancer may have additional requirements, such as the need for caregivers, transportation, and home care support, to be able to safely undergo cancer therapy. Social isolation and low levels of social support have been associated with an increased incidence of cancer as well as higher mortality risk in patients with cancer (27,28). Increased social isolation is also a risk factor for poor tolerance of the adverse effects of cancer treatment (29).

Assessment of Physical Function

Oncologists usually measure physical function using subjective scales such as the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) or Karnofsky performance status scales. Physical function can also be assessed by objective measures of performance, including gait speed, grip strength, balance, and lower extremity strength, which are more sensitive. Decreases in these measures are associated with worse clinical outcomes (30). A commonly used test for gait speed is Timed Up and Go (TUG), which is brief and simple to implement in clinical settings (7). Gait speed is an important indicator in older persons, as it has been shown to be an independent predictor of mortality across numerous population-based studies (9). Grip strength is also important in cancer patients and is relatively quick and easy to assess; however, the availability of a handheld dynamometer may be a barrier. Grip strength is a measure that correlates with sarcopenia and has been shown to be associated with adverse outcomes in patients with cancer (31,32).

Falls

Falls are major events and major health concerns in the older population because they are related to the person’s ability to live independently. More than one-third of persons 11165 years of age or older fall each year, and in half of such cases the falls are recurrent (33). They are typically multifactorial and due to intrinsic factors (e.g., visual impairment, muscle weakness, poor balance, orthostasis), extrinsic factors (e.g., polypharmacy, medication side effects), or environmental factors (e.g., loose carpets, poor lighting). Falls should be thoroughly evaluated using a multidisciplinary approach (physical therapy, occupational therapy, home safety, medication evaluation, evaluation for cataracts, etc.) with the goal of minimizing the risks without compromising functional independence. The Tinetti Gait and Balance Scale is a rapid, reproducible assessment tool for the evaluation of fall risks, gait, and balance (12). The test is scored on the patient’s ability to perform specific tasks. Time to complete is 10 to 15 minutes and interrater reliability was found to be greater than 85%.

Functional Status

An assessment of functional status includes daily living dependence scales and determination of whether a patient needs any assistance on instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) or activities of daily living (ADLs). IADLs generally refer to tasks that are needed to live independently in the community and include shopping, transportation, using the telephone, managing finances, medication management, cooking, cleaning, and doing laundry (6). ADLs are basic self-care skills needed in order to live independently in the home (as opposed to an institutionalized setting), and include bathing, dressing, grooming, toileting, transferring, feeding, and continence (5). Assessing ADLs and IADLs captures additional information not obtained by assessing performance status alone.

Nutritional Status

The incidence of malnutrition in the elderly population is very significant. Nutritional status should be assessed as part of any GA, as malnutrition and weight are significant adverse factors in older patients and in patients with cancer. Although there is not one clear screening tool that is preferred, screening tools that have been used include body mass index (BMI), unintentional weight loss, or longer validated tools such as the Mini Nutrition Assessment (MNA) (17). The MNA is well validated and correlates highly with clinical assessment and objective indicators of nutritional status; because of its validity in screening and assessing the risk of malnutrition, the MNA should be integrated into the GA (34). Malnutrition is associated with treatment complications in patients receiving chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or surgery, and is also associated with increased mortality (35–40).

Psychological Status

Depression and psychological distress are common problems that impact patients with cancer and lead to poor quality of life, high caregiver burden, and functional decline. Although studies have suggested that anxiety may decrease with aging, there is a consistent relationship between depression and increased age (41). Depression is highly prevalent in older persons with cancer, with a range of 10% to 65% across 112different GA studies (42). Patients with cancer and depression are less likely to receive definitive treatment, and hence experience worse survival compared to those without depression (43). Brief screening tools may help clinicians in busy settings detect patients who are experiencing severe psychological distress. The distress thermometer (DT) is a single item that asks patients to rate their distress in the past week on a 0 (“no distress”) to 10 (“extreme distress”) scale (22). It offers an efficient means of identifying patients with advanced cancer who have severe distress. It has been used in psycho-oncology and validated for patients and cancer patients’ families (44).

GA IN THE SURGICAL CANCER PATIENT

Geriatric surgical patients have unique vulnerabilities that require assessment beyond the traditional preoperative evaluation (45). Because the physiologic reserve of an elderly patient is not always apparent, established assessment tools such as the American Society of Anesthesiology Physical Status Classification System (ASA classification) are not sufficiently sensitive to predict differences in operative risks (46). GA has the potential for identifying patients at risk for postoperative adverse events such as mortality, disability, institutionalization, and cognitive decline, and it provides an opportunity to implement perioperative interventions.

The importance of GA in predicting surgical outcomes has been reported. Preoperative impaired cognition, low albumin level, previous falls, low hematocrit level, any functional dependence, and a high burden of comorbidities were most closely related to 6-month mortality and postdischarge institutionalization in patients undergoing major thoracic and abdominal operations (45). Baseline cognitive impairment is related to increased number of postoperative complications, length of stay, and long-term mortality (47). In the Preoperative Assessment of Cancer in the Elderly (PACE) study, functional dependency, fatigue, and abnormal performance status were associated with a 50% increase in the relative risk of postoperative complications (48). In patients greater than 65 years of age, lower Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) score and older age were significantly associated with the development of postcystectomy delirium, and those who developed delirium were more likely to face readmission and reoperation (49). In patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy, older age and worse scores in GA predicted major complications, longer hospital stays, and surgical intensive care unit (ICU) admissions (50).

ASSOCIATION OF GA WITH CANCER TREATMENT OUTCOMES

Over the last decade, GA has been integrated into oncology care and has contributed to uncovering a substantial proportion of deficits in older cancer patients that would otherwise have gone unrecognized (42). Although results are difficult to compare, as different studies have used different components of GA, the most frequently assessed domains were functional status, comorbidity, depression, 113and cognition (51). GA has been found to influence treatment decisions, which included reducing the intensity of chemotherapy, lowering the amount of prescribed medications, or providing additional supportive care (1). GA not only helps to better inform treatment decision making, but also helps to better tailor individualized treatment to an older patient who might otherwise be at greater toxicity risk. A prospective multicentric study on the large-scale feasibility and usefulness of GA in clinical oncology showed that GA detected unknown geriatric problems in 51% of patients more than 70 years old, and when physicians became aware of the results, geriatric interventions and adapted treatment occurred in 25.7% and 25.3% of the patients, respectively (52).

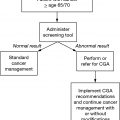

GA is time consuming and requires close cooperation between oncologists and geriatricians. An important practical aspect of GA is the feasibility of incorporating it into a busy clinical oncology practice. Key considerations in performing the GA include the resources available (staff, space, and time), patient population (who will be assessed), what GA tools to use, and clinical follow-up (who will be responsible for using the GA results for the development of care plans and who will provide follow-up care). Important challenges in implementing GA in clinical practice include not having easy and timely access to geriatric expertise, patient burden of the additional hospital visits, and the need to establish collaboration between the GA team and oncologists regarding expectations of the population referred for GA and expected outcomes of the GA (53). A two-step approach has been suggested: the development of screening tools that would sort out who is an “older adult” with intact physiology and psychosocial conditions, and who is a vulnerable elder cancer patient in need of further multidisciplinary evaluation (see Chapter 14).

For risk stratification prior to chemotherapy, briefer tools based on GA such as the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) (54) score and the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) (55) score may be more efficient in determining a patient’s predicted chemotoxicity risk.

1. The CARG score was developed in a prospective multicenter cohort study of 500 patients age 65 or older with cancer who were receiving chemotherapy. All patients underwent a GA that included measures of functional status, comorbidity, psychological state, social activity, social support, and nutrition. A predictive model was developed and validated (56), including GA variables along with patient demographic and clinical variables to predict grade 3 to 5 toxicity with chemotherapy administration. Higher risk scores were associated with increased chemotoxicity.

www.mycarg.org/Chemo_Toxicity_Calculator

2. The CRASH score was developed in a prospective, multicenter study among patients 70 and older receiving chemotherapy. GA variables were included along with patient clinical variables and chemotoxicity risk, and predictive models were developed for grade 4 hematologic and for grade 3 to 4 nonhematologic toxicity (55).

www.moffitt.org/eforms/crashscoreform/

TAKE HOME POINTS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree