James W. Kazura

Tissue Nematodes (Trichinellosis, Dracunculiasis, Filariasis, Loiasis, and Onchocerciasis)

Tissue-dwelling nematode (roundworm) infections are widely distributed throughout the world. The health and socioeconomic impact of these infections is greatest in resource-poor settings in the tropics and subtropics, although populations in temperate and industrialized regions of the world continue to be at risk for infection and morbidity. Like all parasitic nematodes, the life cycle of these multicellular organisms includes five distinct stages: adult male or female worms and four larval stages distinguished from each other by a molting process that involves shedding of the parasite’s surface cuticle and organ system differentiation dictated by developmentally regulated changes in gene expression. With the exception of Trichinella spp., which are transmitted directly to humans by ingestion of contaminated meat, infection involves obligatory development in and subsequent transmission by blood-feeding invertebrate arthropods (the filariases) or swallowing of small freshwater crustaceans (copepods). Adult worms do not multiply in the human host and, therefore, the likelihood of developing a high enough worm burden to cause morbidity is directly related to the duration and intensity of exposure to vectors harboring infective larvae. Definitive diagnosis is made by microscopic visualization of parasites isolated from or present in host tissue, although this may be difficult or not indicated in all cases. Simple and inexpensive measures can be taken to avoid infection. Global efforts are under way to eliminate some tissue nematode infections as public health problems or even eradicate them by permanently stopping transmission. Effective and safe anthelmintic drugs are available for the majority of these infections.

Infections acquired by eating contaminated meat and swallowing copepods harboring infective larvae are considered first. Filarial infections transmitted by blood-feeding insects are described next.

Trichinellosis

Trichinellosis is acquired when undercooked meat of domestic pigs, horses, or game containing infective larvae of various Trichinella spp. is consumed. Symptomatic infections characterized by diarrhea, myositis, fever, and periorbital edema develop when large numbers of larvae are ingested.

Life Cycle of Trichinella

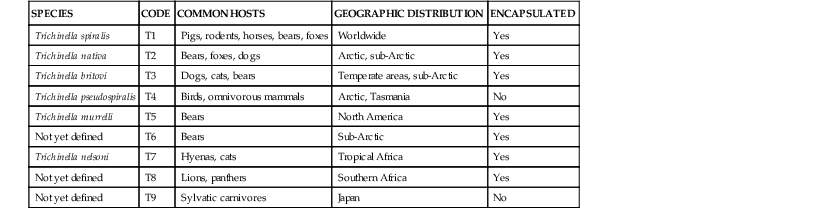

Members of the Trichinella genus are zoonotic nematodes that infect carnivorous and omnivorous mammals in various ecologic and climatic settings.1 Recent genomic and phylogenetic analyses indicate that of the 11 known species there are two clades distinguished by the presence or absence of encapsulated third-stage larvae that have parasitized striated muscle cells (Table 289-1).2,3 The two clades are estimated to have diverged from a common ancestor 15 to 20 million years ago. Trichinella spiralis, a species distributed throughout the world that infects pigs, rodents, and horses has historically been the most common cause of human infection. Trichinella spp. of wild game are of increasing importance in areas where food safety measures and livestock practices have led to a reduction in T. spiralis.4

The parasite life cycle begins with the enteral phase when meat containing infective third-stage larvae is eaten. Larvae of approximately 1 mm in length are liberated after digestion of the encapsulated cyst wall in the acid-pepsin environment of the stomach. These larvae pass rapidly to the lumen of the small intestine where they parasitize cells of the columnar epithelium. Four molts occur over 10 to 28 hours, culminating in the development of mature adult female and male worms in the epithelium of the small intestine. Fecund female worms produce and release first-stage (newborn) larvae that initiate the systemic phase of infection when they penetrate the gut wall and enter the lymphatics and eventually the blood circulation via the thoracic duct. Newborn larvae are dispersed in capillary beds throughout the body and ultimately parasitize striated muscle cells. After entering muscle, the larvae molt, encyst, and undergo development to become infective third-stage larvae within 15 days.5 T. spiralis infective larvae encapsulated in collagenous cysts may remain viable for months to years. The cysts may calcify and be visible on radiographs.

Epidemiology

Trichinellosis historically has been associated with the consumption of undercooked pork products prepared from domestic swine. The epidemiologic significance of this source of infection has diminished over the latter part of the 20th century as the practice to feed pigs garbage containing Trichinella-infested meat scraps or rodents has been eliminated. Notably, outbreaks of T. spiralis infection associated with the consumption of pork from domestic swine have recently been observed in several countries in Eastern Europe and in western China.6,7 Consumption of meat from horses and wild game (boar, deer, bear, cougar, and walrus in areas where sylvatic trichinellosis is endemic) may also be the source of human infection. T. spiralis is the most common cause of human infection; Trichinella britovi, Trichinella pseudospiralis, and Trichinella murrelli often underlie cases associated with consumption of wild game.

Pathogenesis and Pathology

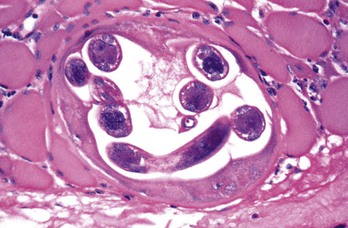

Pathologic manifestations of infection first appear in the gastrointestinal tract. Two to 3 weeks after ingestion of contaminated meat and establishment of adult worms in the upper small intestine, local villous atrophy and mucosal and submucosal infiltration with neutrophils, eosinophils, and macrophages develop. However, the most characteristic pathologic change induced by the parasite is evident in skeletal muscle fibers. Histologically, edema and basophilic degeneration are present. Coiled worms, cyst walls resulting from parasitization of muscle cells, and infiltrates consisting of eosinophils and lymphocytes may be observed (Fig. 289-1). Although nonstriated muscle and other host tissues do not support the complete development of Trichinella to infective third-stage larvae, newborn larvae that disseminate to the myocardium, lung, and central nervous system in heavily infected individuals may cause local inflammation and tissue damage that have serious pathologic consequences (e.g., myocarditis, encephalitis, meningitis).

Clinical Manifestations

Based on observations made under circumstances in which a common source of infested meat has been identified, the majority of infected people are asymptomatic. Morbidity is most likely to develop in individuals who have ingested the highest parasite inocula. Watery diarrhea is the most common manifestation during the enteral phase of infection. Vomiting, abdominal discomfort, and nausea may also be observed. Prolonged diarrhea and other gastrointestinal symptoms in Native American adults who traditionally consume polar bear or walrus meat infested with Trichinella nativa have been suggested to reflect immunity acquired as a result of earlier infections. Facial and periorbital edema, fever, weakness, malaise, myalgia, urticarial rash, conjunctivitis, and conjunctival and subungual hemorrhages appear during the systemic phase when newborn larvae disseminate. These signs and symptoms are most severe and peak 2 to 4 weeks after ingestion of contaminated meat.8–11 Weakness and myalgia appear first and are most severe in the extraocular, masseter, and neck muscles. Patients with high infection burdens may die of myocarditis, encephalitis, or pneumonia that becomes progressively severe after 4 to 8 weeks. It has been suggested that trichinellosis can lead to chronic muscle pain and weakness.

Diagnosis

Trichinellosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with myositis, eosinophilia, fever, elevated creatine phosphokinase and lactate dehydrogenase levels, and signs consistent with systemic dissemination of newborn larvae as described previously. Questioning regarding a history of consumption of undercooked meat from wild or farmed game, such as bear and boar or pigs raised in noncommercial and unregulated farms, is informative. It is also helpful to determine whether a similar illness has developed in others who have consumed the same food. Antibodies to Trichinella spp. can be detected by a variety of techniques12 (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is now used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Seroconversion usually occurs by approximately 3 weeks after ingestion of infective larvae. A biopsy specimen of painful muscle may reveal the presence of Trichinella spp., although this procedure is not recommended in most situations. It is useful to obtain a sample of the meat suspected to harbor the parasite because this can be used to confirm the origin of the infection. Various Trichinella spp. can be differentiated by DNA-based technologies such as polymerase chain reaction assay.13

The differential diagnosis of trichinellosis observed during the enteral phase of infection includes a wide variety of causes of gastroenteritis and diarrheal illnesses. During the systemic phase of infection, febrile illnesses including influenza and typhoid fever, connective tissue diseases such as dermatomyositis, and angioneurotic edema should be considered.

Therapy

Currently, no anthelmintic drug has proved effective against newborn larvae or maturing first-stage larvae that cause myositis and other signs and symptoms that appear during the systemic phase of infection. Systemic corticosteroids in conjunction with mebendazole may be used in patients with severe illness, although proven benefit for this approach is lacking.

If the diagnosis is made during the enteral phase of infection (e.g., within 1 to 2 weeks of eating contaminated meat or when gastrointestinal signs and symptoms are present), mebendazole (200 to 400 mg orally three times daily for 3 days, then 400 to 500 mg orally three times daily for 10 days for all ages) may be used to eliminate adult worms from the small intestine.14 Albendazole (400 mg orally twice daily for 8 to 14 days) may also be used.

Prevention

Awareness of and compliance with safety regulations prohibiting the use of garbage as a source of food for domestic animals, control of rodents, segregation of livestock from wild animals, and proper preparation of meat from wild animals will reduce the risk for infection with Trichinella spp. Inspection of meat for Trichinella is ideally done by direct dissection and visualization of encysted larvae.

Cooking meat to a temperature 55° C or higher (until pink fluid or flesh is not visible) kills Trichinella spp. Storage in a freezer (−15° C) for 3 or more weeks kills T. spiralis in pork, but this is not effective for Trichinella spp. larvae in horse and game meat. Drying, smoking as in the preparation of jerkies, and salting of meat should not be relied on to kill Trichinella.

Haycocknema Perplexum Infection

Haycocknema perplexum is a species of Muspiceoidia nematodes that has been observed in the tissues of Australian mammals and marsupials. Adult and larval stages of the nematode have been identified in muscle biopsy specimens of Australian patients from Tasmania and tropical northern Australia who present with chronic myositis, peripheral muscle weakness, and dysphagia accompanied by eosinophilia and elevated creatine phosphokinase level.15,16 Muscle weakness improved and killing of parasites was observed after administration of multiple doses of albendazole. Corticosteroids are not indicated because this class of drugs may exacerbate muscle weakness and lead to a reduction of eosinophilia that misleads the clinician to conclude that a beneficial effect on a connective tissue disease such as polymyositis has occurred.

Dracunculiasis

Dracunculiasis, or Guinea worm disease, is caused by the parasitic nematode Dracunculus medinensis. Once prevalent throughout southern Asia and parts of the Middle East, as of 2012, indigenous infections were limited to Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, and South Sudan, with the majority in South Sudan.17 The parasite causes debilitating skin lesions and secondary bacterial infections. Dracunculiasis has great socioeconomic impact in affected rural communities.

Life Cycle of the Parasite

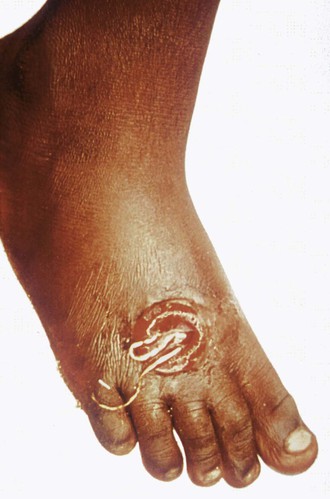

Humans are infected by swallowing fresh water from stagnant pools containing minute fresh water crustaceans (copepods) harboring infective larvae of D. medinensis. When the copepods are digested in the acid-pepsin environment of the stomach, larval forms are released from the body of the crustacean, after which they penetrate the wall of the small intestine and migrate through the thoracic musculature. Sexually mature male and female worms develop over 2 to 3 months. Gravid female worms mature over 10 to 14 months, migrate throughout the body, and ultimately reach the skin, particularly over the ankles, feet, and lower leg (Fig. 289-2). When skin comes into contact with water, the female worm (which may reach a length of 1 m) induces a local blister that eventually ruptures. Large numbers of larvae are released into the water when prolapsed loops of the uterine cavity contract. The motile free-swimming larvae infect copepods. D. medinensis larvae become infective for humans after further development in the intermediate copepod host over a 2-week period.

Epidemiology

Clinical manifestations of D. medinensis infection appear approximately 1 year after ingestion of contaminated water and are highly seasonal because they coincide with the appearance of stagnant pools of surface water that vary according to local climatic conditions. The prevalence of dracunculiasis is a strong indicator of socioeconomic development because communities are at highest risk where there is inadequate treatment of contaminated water, access to safe drinking water, and separation of bathing and drinking facilities.

Clinical Manifestations

Signs and symptoms of dracunculiasis appear approximately 1 year after infection when fecund adult female worms appear near the surface of the skin. The initial presentation is a painful papule that enlarges over hours to days to form a blister that allows a portion of the worm to emerge from the skin. The blister may be accompanied by local erythema, urticaria, fever, nausea, and pruritus. The entire worm may emerge over a period of several weeks. Complications include secondary bacterial infections that may lead to sepsis, local abscesses, and pyogenic arthritis. Affected individuals are incapacitated for approximately 8 weeks. The vast majority of worms emerge from the lower leg, ankle, and foot, although aberrant sites of emergence have been reported (e.g., head, neck, genitalia).

Diagnosis and Therapy

Dracunculiasis is diagnosed by the appearance of the skin blister and adult worm (see Fig. 289-2). No anthelmintic drugs are known to be effective against D. medinensis. Application of wet compresses to the affected skin, administration of analgesics, and prevention of secondary bacterial infection by the use of topical antibiotics are recommended. Worms should be slowly and gently extracted over a period of several days using a small stick because breaking the worm can lead to allergic reactions and secondary bacterial infection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree