Step 1

Surgical Anatomy

- ♦

The first documentation of the thyroid gland was by Galen in the second century. Then, in 1656, the anatomist Thomas Wharton coined the term thyroid, derived from the Greek word thyreos for shield. Goiter, defined as thyroid gland enlargement, is derived from the Latin term tumidum guttur , or swollen throat.

- ▴

Worldwide, iodine defiency is the most common cause of goiter; in the United States, Hashimoto’s disease is the most common etiology.

- ▴

Although no debate exists regarding the definition of goiter, there is great debate about how to describe its extent beyond the thoracic inlet, defined by the upper border of the manubrium anteriorly, the first thoracic vertebrae posteriorly, and the first rib and costal cartilage laterally. Terms such as retrosternal, substernal, intrathoracic , and mediastinal have all been used.

- ▴

- ♦

The substernal goiter was first described in 1749 by Albert von Haller. Substernal goiters today have an incidence of approximately 1 in 5000 individuals.

- ▴

Most commonly, as described by deSouza and Smith, the term substernal goiter is used when more than half of the thyroid gland is located below the thoracic inlet.

- ▴

Others have described it with respect to its relationship to the aortic arch. have even proposed a classification to coincide with the type of operative approach one needs to consider: grade I, defined as above the aortic arch (transcervical approach); grade II, aortic arch to pericardium (manubriotomy); and grade III, below the right atrium (median sternotomy).

- ▴

- ♦

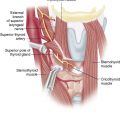

The thyroid gland normally weighs approximately 20 grams and is located anterior to the trachea. It is composed of paired lateral lobes with a central isthmus and extends from just below the laryngeal prominence to the sixth tracheal ring. It is completely enveloped by pretracheal fascia. Immediately anterior to the thyroid are strap muscles, including the sternohyoid, sternothyroid, omohyoid, and thyrohyoid muscles.

- ▴

The main arterial supply consists of the superior thyroid arteries, derived from the external carotid arteries; the inferior thyroid arteries, derived from the thyrocervical trunk; and occasionally (<10%) the thyroid ima, which is derived from either the aortic arch or the brachiocephalic trunk.

- ▴

The venous drainage consists of paired superior and middle thyroid veins that empty into the internal jugular veins and paired inferior thyroid veins that drain into the internal jugular and innominate veins.

- ▴

- ♦

It is imperative that the surgeon be aware of the intimate anatomic details of the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve.

- ▴

The right recurrent laryngeal nerve emanates from the vagus nerve, courses around the subclavian artery, and travels posteriorly to the carotid artery before ascending in the tracheoesophageal groove to the cricothyroid muscle. In rare instances (<1%), a nonrecurrent recurrent laryngeal nerve will be present, often associated with a right subclavian artery originating directly from the aortic arch.

- ▴

On the left, the recurrent laryngeal nerve also emanates from the vagus nerve and crosses under the aortic arch before ascending in the tracheoesophageal groove. Even more uncommon is the presence of a left nonrecurrent recurrent laryngeal nerve, which can occur in the setting of a right-sided aortic arch with situs inversus. The anatomy of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve also requires careful study. The path in which the main trunk travels before its terminal branching has been classified by Cernea and colleagues: type 1 crosses the superior thyroid artery more than 1 cm above the upper pole of the thyroid gland; type 2a crosses the superior thyroid artery less than 1 cm above the upper pole; and type 2b crosses the superior thyroid artery below the border of the upper pole.

- ▴

- ♦

Knowledge of parathyroid gland anatomy in relation to the thyroid gland is also essential. The four parathyroid glands are normally situated immediately adjacent to the thyroid gland. The paired superior parathyroid glands, derived from the fourth branchial pouch, are usually located posterior to the recurrent laryngeal nerve; the paired inferior parathyroid glands, derived from the third branchial pouch, are usually located anterior to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. However, all glands can be located more anteriorly and be intimately associated with the thyroid gland. The inferior parathyroid glands can also be found within the thymus.

Step 2

Preoperative Considerations

- ♦

Large goiters can present a challenge to the surgeon, especially when they are recurrent or intrathoracic.

- ▴

Recurrent goiters may occur in up to 37% of patients postoperatively as reported by in a series of patients who previously had undergone thyroidectomy for substernal goiter. The most common explanation for this high recurrence rate, however, is less than total thyroidectomy. Although some advocate unilateral thyroid lobectomy even in the presence of contralateral nodularity, total thyroidectomy is generally recommended as the procedure of choice for multinodular goiter.

- ▴

Large goiters have an intrathoracic component as often as 20% of the time. Because a goiter may also extend into the posterior mediastinum, intrathoracic may be a more appropriate term than substernal to describe the goiter’s extent.

- ▴

- ♦

Factors that may facilitate migration of the goiter include gravity, negative intrathoracic pressure, and potential space within the mediastinum. On rare occasions a goiter may originate de novo from the mediastinum. It is important that the surgeon be cognizant of this entity because the blood supply of a mediastinal thyroid will also originate within the mediastinum, and the patient may require a median sternotomy. The majority of substernal goiters, however, can be resected via a cervical approach.

- ♦

Indications for surgical resection of large or substernal goiters include growth despite thyroid hormone replacement or compressive symptoms such as stridor, dyspnea, or orthopnea. Other symptoms that warrant operative intervention include dysphagia, venous congestion, recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, and hyperthyroidism. Radiographic signs such as tracheal deviation or stenosis also necessitate surgery. Some physicians even advocate thyroidectomy if there is a retrosternal component, irrespective of symptoms. It is known that postoperative morbidity occurs more commonly in patients who undergo thyroidectomy for large and substernal goiters compared to patients who have goiters contained within the neck.

- ♦

One of the challenges in managing patients with large and substernal goiters is a difficult airway. Preoperatively, the patient’s airway should be evaluated by direct or indirect laryngoscopy to determine if vocal cord paralysis or significant tracheal deviation or narrowing exists.

- ♦

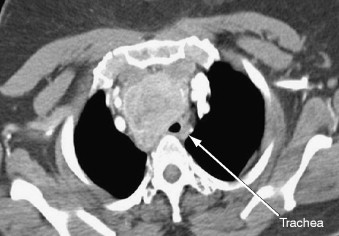

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck and chest will help to determine the degree of tracheal stenosis as well as the extent of the lesion below the thoracic inlet ( Figs. 3-1, 3-2, and 3-3 ). It should be obtained when the clinical history or physical examination suggests airway compression or substernal extension.

Figure 3-1