The Postsurgical Breast

A wide variety of mammographic findings are seen after surgical procedures on the breast. Surgical procedures—including core needle biopsy, excisional breast biopsy, wide excision or segmental mastectomy, subcutaneous or modified radical mastectomy with reconstruction, reduction mammoplasty, and lumpectomy with radiation therapy—produce a spectrum of classical and unusual findings. Critical to an accurate analysis of a mammogram and to determination that findings are of postsurgical origin is knowledge of the history and clinical examination of the patient.

It is of help to place a wire or BB marker on the skin to avoid repeating films because of uncertainty about positions of scars. If this is not done, then it is absolutely necessary that the technologist be responsible for clearly marking the location and orientation of any scars on a drawing of the breast. The surgical site is sometimes demarcated with surgical clips, particularly in cases of lumpectomy performed for carcinoma. Additionally, it is equally important to document the location and size of any palpable masses and particularly their relationship to the surgical scar.

In interpreting a mammogram of a postsurgical breast, it is important for the radiologist to compare present studies with previous studies. Temporal changes are reflective of the normal evolution of postsurgical findings. Also, knowledge of the appearance of the original lesion in patients who have undergone lumpectomy and correlation with the specimen film is helpful to identify residual disease.

Postbiopsy Changes

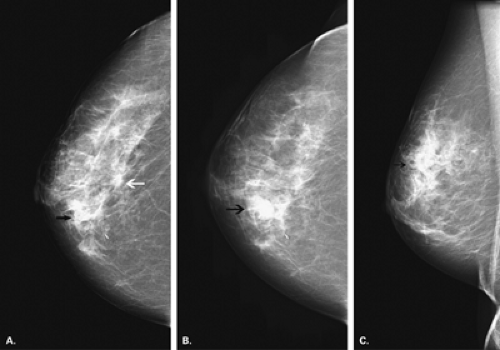

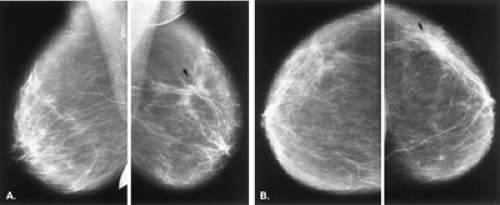

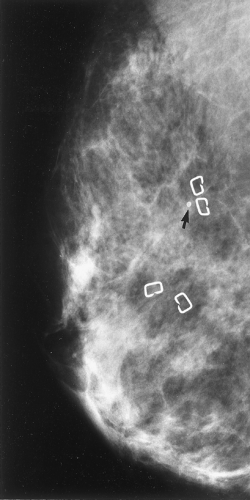

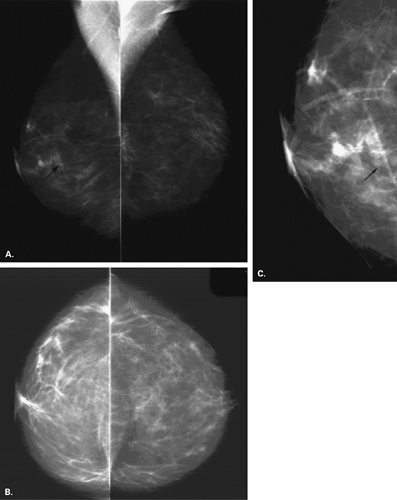

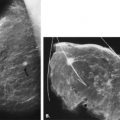

Immediately after a needle biopsy of a breast lesion, there may be a small amount of air at the biopsy site, especially when a vacuum-assisted biopsy is performed. Occasionally, there also may be irregular increased density at the site from edema and hematoma formation. Unless there is significant bleeding during the biopsy, the changes are subtle. If there is a puncture of a vessel during a needle biopsy, a hematoma may form. If the hematoma dissects through the tissue, an amorphous ill-defined density is seen on mammography. If a hematoma is more localized, then the appearance is that of a relatively circumscribed mass (Fig. 12.1). These findings are typically observed immediately after the biopsy on the postprocedure mammogram. In most cases, however, there is no long-term mammographic finding after a needle biopsy.

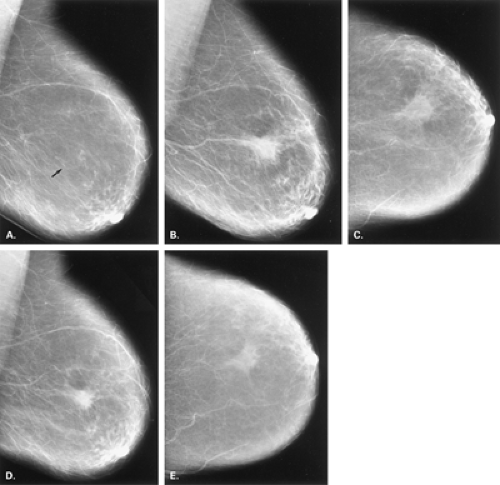

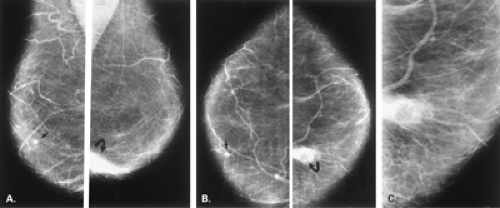

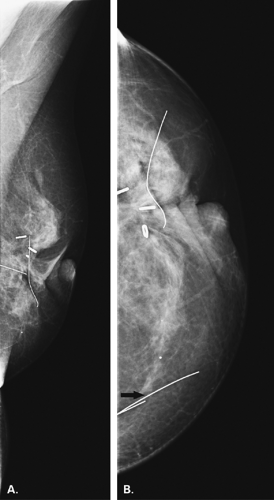

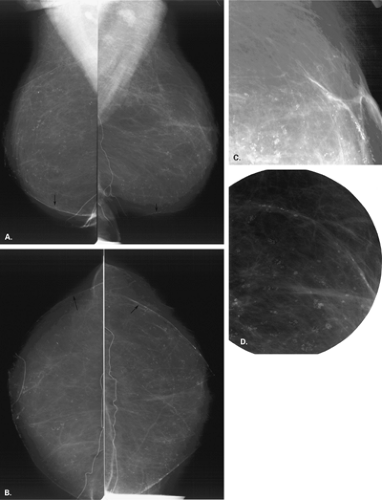

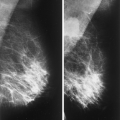

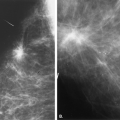

The mammographic findings associated with excisional biopsy are localized to the area of the biopsy site. It is, therefore, important to correlate the position of the scar to the mammographic findings and to be aware of the temporal changes that are expected postsurgically. In a study of 1,049 breast biopsies, Sickles and Herzog (1) found mammographic abnormalities attributed to postsurgical changes in 474 (45%). Normal postsurgical changes include localized skin thickening or retraction, an asymmetric glandular defect, architectural distortion, contour deformity of the breast, hematoma or seroma, fat necrosis formation, parenchymal scarring (Figs. 12.2,12.3,12.4,12.5,12.6), calcifications of fibrosis (Figs. 12.7 and 12.8), fat necrosis and sutures, and opaque foreign bodies (1,2) (Figs. 12.9,12.10,12.11).

Skin thickening is localized to the biopsy site unless there is superimposed infection, in which case a more generalized thickening is present. A contour deformity may be associated with the skin thickening. Skin thickening is maximum on mammography during the first 6 months after biopsy and gradually diminishes. In a majority of patients who have undergone a lumpectomy or excisional biopsy for benign disease, the focal skin thickening is nearly inapparent on mammography after several years.

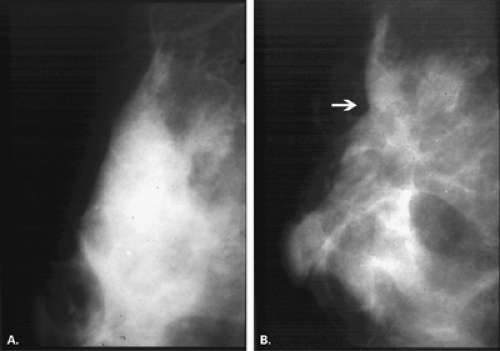

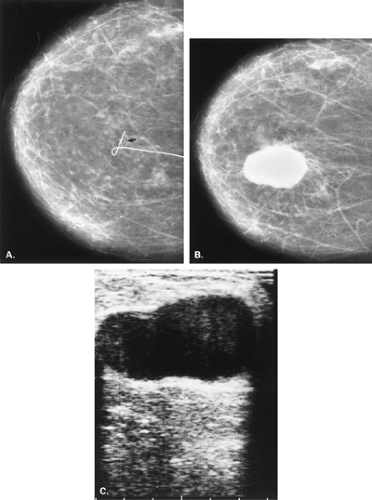

A hematoma may be seen at the biopsy site on a mammogram performed soon after biopsy. Postoperative hematoma or seromas are seen more commonly if a drain has not been placed and may actually be related to an improved cosmetic result with a lesser degree of contour

deformity (3). On mammography, fluid collections are usually relatively circumscribed medium- to high-density masses and may range from 2 to 10 cm in diameter. In a series of postlumpectomy patients who were referred for radiotherapy, Mendelson (3) found postoperative fluid collections in 47%. On ultrasound, hematomas or seromas are relatively smooth and anechoic but may contain some internal echoes or debris, depending on the degree of organization (4). Because fluid collections may contain debris even if they are not infected, the clinical findings are of more help to suggest the presence of superimposed infection.

deformity (3). On mammography, fluid collections are usually relatively circumscribed medium- to high-density masses and may range from 2 to 10 cm in diameter. In a series of postlumpectomy patients who were referred for radiotherapy, Mendelson (3) found postoperative fluid collections in 47%. On ultrasound, hematomas or seromas are relatively smooth and anechoic but may contain some internal echoes or debris, depending on the degree of organization (4). Because fluid collections may contain debris even if they are not infected, the clinical findings are of more help to suggest the presence of superimposed infection.

Areas of architectural disturbance are a common finding after surgery and include asymmetric decrease in glandular tissue from resection that does not change over time (1), architectural distortion, and focal increased density or parenchymal scar and fat necrosis. As a hematoma resolves, it is usual to see some residual, irregular increased density and/or distortion. Architectural distortion was the second most common postsurgical finding after skin thickening by Sickles and Herzog (1) in the evaluation of 474 postoperative breasts.

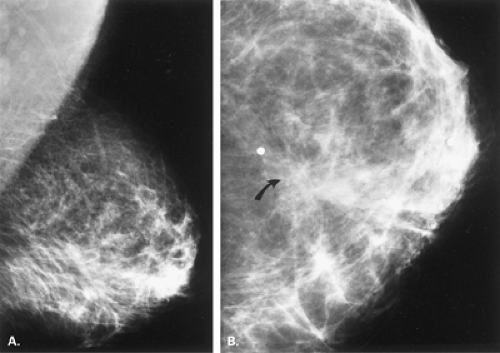

The changes of increased density and architectural distortion are maximum at 0 to 6 months after surgery and gradually diminish over time (1). The presence of entrapped fat within the distortion is also suggestive of scar. Scars also tend to have a different shape on two views, appearing as a spiculated area of architectural distortion on one view and as much less distorted on the orthogonal view. Often the extension of the distortion to the skin scar is also noted.

When one is interpreting a spiculated density as a postsurgical change, it is important to review the mammogram before biopsy to confirm that the lesion removed was in fact in the area of concern and, if nonpalpable, was present in the specimen. The most helpful factor that can aid one in making the diagnosis of “postsurgical change” on subsequent studies is a mammogram at 3 to 6 months after biopsy (1). This is particularly important when the biopsy demonstrated an atypical lesion.

Calcifications of fat necrosis form at variable times after biopsy but usually later than 6 months. These calcifications are typically ringlike, with lucent centers, and may be small (liponecrosis macrocystica calcificans) or larger oil cysts (radiolucent masses with eggshell calcifications). Occasionally, fat necrosis may be associated with clumps of irregular but rather coarse microcalcifications. Other forms of calcification that occur postoperatively include ringlike dermal calcifications in the scar, particularly in keloids. Calcified sutures, which are in linear or knot

shapes, are observed postoperatively but more frequently in patients treated with radiotherapy (5).

shapes, are observed postoperatively but more frequently in patients treated with radiotherapy (5).

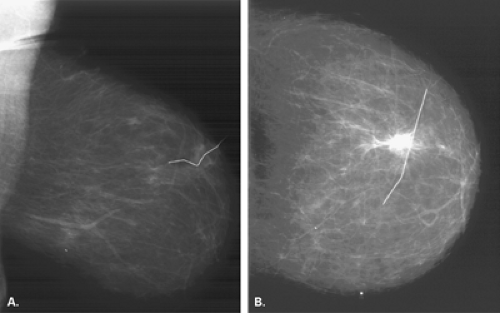

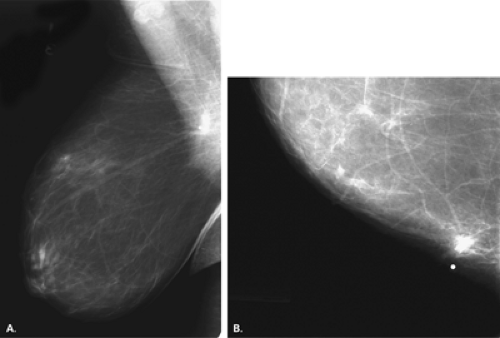

Foreign bodies left in the breast include surgical clips (often used for marking a tumor bed for location of a boost dose of radiotherapy) and sutures that may calcify. Inadvertent transection of a needle localization wire and lack of its retrieval will result in the observation of a small segment of wire in the breast. Another cause of an iatrogenic foreign body in the breast is the inadvertent severing of the tip or cuff of a central venous catheter for chemotherapy, which may be embedded in the upper inner aspect of the breast (6).

Reduction Mammoplasty

Breast reduction is performed for cosmetic reasons (to treat macromastia) or to achieve symmetry of the contralateral breast after the patient has undergone mastectomy with reconstruction. The surgical procedure involves elevation of the nipple, resection of glandular tissue, and skin removal (7). If there is a nipple transposition procedure, the nipple-areolar complex remains attached to the lactiferous ducts, and the whole complex is transposed upward. In a transplantation procedure, the nipple-areolar complex is severed from the ducts and is transplanted upward (7).

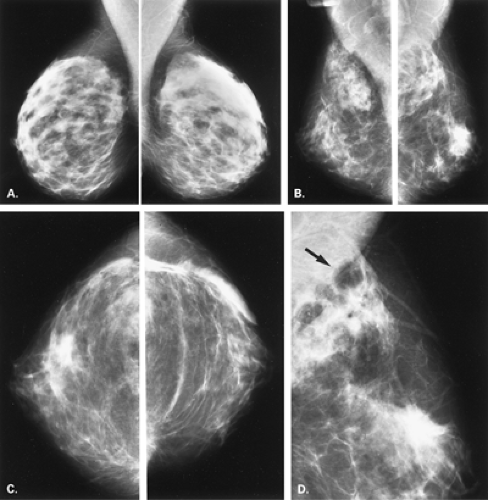

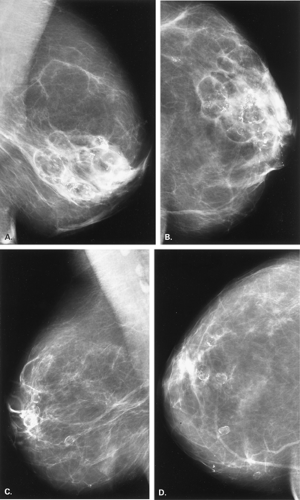

Mammographic findings vary with the type of procedure performed. In patients with a transposition, the subareolar ducts are in a normal relationship with the nipple-areolar complex, but there is a disruption of this orientation after transplantation procedures. Miller et al. (7) found parenchymal redistribution, with most of the fibroglandular tissue below the level of the nipple, as the most common finding in 24 patients who had undergone reduction mammoplasties. Elevation of the nipple was also a common finding, along with thickening of the skin of the lower aspect of the breast and the areola (7). There may be disorientation of the normal parenchymal pattern, with swirled patterns of tissue distribution (8). The scars on the skin may be evident on the mammogram as circumlinear densities traversing the inferior aspect of the breast (Figs. 12.12,12.13,12.14,12.15,12.16,12.17,12.18,12.19).

Mandrekas et al. (9) described fat necrosis in 1.7% of patients following breast reduction. These patients all presented with a palpable mass that was located deep in the breast near the pectoralis major muscle. The lesion resembled a cancer on mammography and ultrasound.

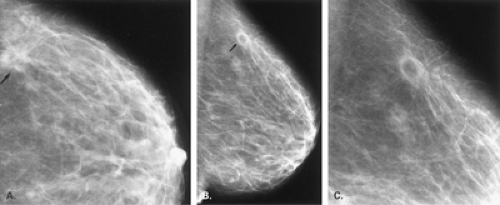

Brown et al. (10) found that periareolar soft tissue changes and inferior pole alterations were present at 6 months in nearly all of 42 patients following breast reduction, and these findings regressed on subsequent studies. In 50% of patients, calcifications occurred after 2 years. In 10% of patients, there was evidence of fat necrosis on mammography.

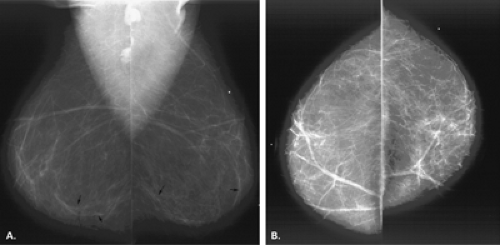

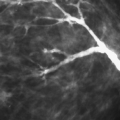

Calcifications are a common finding in patients who have had breast reductions (3). Dermal calcifications, which are smooth and round, may occur in the areola (7) or in scars. Areas of fat necrosis are more common in patients who have undergone reduction than those who have had routine biopsies. Calcifications may be eggshell shaped in the walls of oil cysts or may be irregular (11) or even lacy in appearance (Fig. 12.20). The calcifications may be extensive and have a coarse pleomorphic appearance, sometimes raising a concern for cancer because of the pleomorphism. Importantly, these calcifications are oriented in the direction of the scars, and correlation with this distribution is helpful in confirming their etiology. Even sutural calcification may be identified after reduction procedures (8) (Fig. 12.21).

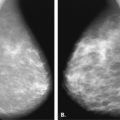

Figure 12.17 HISTORY: A 45-year-old woman after bilateral reduction mammoplasties, with firm nodularity in both subareolar areas. MAMMOGRAPHY: Right MLO (A) and CC (B) views and left MLO (C) and CC (D) views. The breasts show primarily fatty replacement. There are extensive areas of calcification in both breasts, more prominent on the right than on the left. Many of the calcifications are thin eggshell or rimlike in areas of liponecrosis macrocystica (fat necrosis). On the right (A and B

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|