Galactography

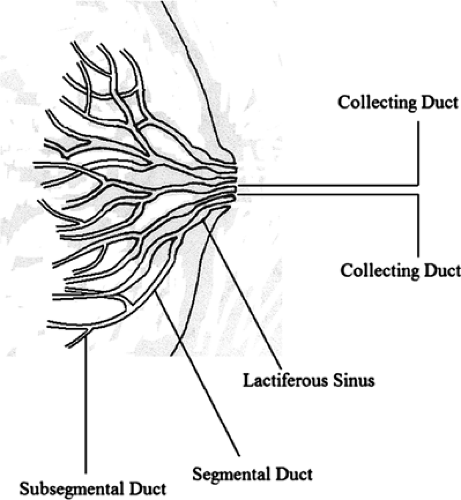

The lactiferous ducts develop from epithelial buds and are affected by the hormonal milieu. The ducts drain the parenchyma and are the conduits of milk in the lactating woman. The duct system is the site of development of most benign and malignant epithelial lesions, and some of these may be associated with nipple discharge.

The evaluation of patients who present with an abnormal nipple discharge includes clinical examination and a variety of tests, such as cytologic analysis, mammography, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), galactography, and ductoscopy. This chapter will focus on the role, technique, and interpretation of galactography.

Nipple discharge in a nonlactating breast can be produced by a variety of conditions, including duct ectasia, fibrocystic change, inflammation, intraductal papilloma, and intraductal carcinoma. The most common cause of a bloody or discharge at all ages is an intraductal papilloma (1). Galactography or ductography can be useful in the evaluation of a spontaneous nipple discharge, particularly when there are no mammographic or physical findings to account specifically for the etiology of the leakage.

Evaluation of Nipple Discharge

Clinical assessment of the patient who presents with nipple discharge is the first step in determining the potential significance of the symptom and the next step in management. Important clinical history includes the duration of symptoms, the color of the discharge, history of trauma, the laterality (unilateral vs. bilateral) and spontaneity of the discharge, and the history of medications, including hormones or hormonal imbalances (2). Clinical examination should include a general examination of the breast with expression of the discharge. A trigger point that when compressed produces the discharge may be identified. This point may indicate the orientation of the abnormal duct. Observation of the color of the discharge and the location of the orifice are important in planning the management and identifying the potential etiology of this symptom. The determination of whether the discharge is uniorificial is an important step in determining whether galactography is necessary.

Nipple discharge from the nonlactating breast may be white, creamy, yellowish, clear, green, serosanguineous, or bloody. Guaiac testing may be useful to analyze for blood in nipple discharge. The most suspicious discharges are those that are uniorificial and serous, serosanguinous, or bloody. The exceptions are bloody discharge related to pregnancy or to trauma. The absence of blood in nipple discharge, however, does not exclude carcinoma (3,4). Ciatto et al. (5) found that a bloody discharge was more frequently associated with cancer than other patterns of discharge. However, serous discharge that is heme negative may be found with carcinoma.

In most cases, yellow, white, or green discharge is related to a systemic etiology and occurs bilaterally and from multiple ducts. This type of discharge is usually not spontaneous and is associated with duct ectasia, fibrocystic change, or hormonal or medicinal causes (6). Discharges that are not spontaneous and are expressible only are usually of benign origin and related to fibrocystic change (7).

The frequency of malignancy in a patient with bloody nipple discharge has been found to be 5% to 28% (1); however, the frequency of carcinoma is 1.6% to 13% in patients with serous discharge (1,8). In a study of 174 women with uniorificial discharge (31% serous and 69% bloody), Tabar et al. (1) found carcinoma in 18 of 174 (10%) patients. Serous discharge was present in 3 of 18 (17%) patients with cancer; 15 of 18 (83%) patients with cancer had bloody discharge. In this study, cytologic analysis of the discharge was not sensitive, with only 2 of 18 of the cancers having suspicious cytology.

Occasionally pregnant women may develop nipple discharge that is bloody. LaFreniere (9) found that both mammography and cytology were negative in five pregnant women with unilateral bloody multiorificial discharge. In all cases, the discharge resolved within 2 months of onset. Table 14.1 describes the etiologies of nipple discharge based on color.

In the presence of a suspicious nipple discharge, further evaluation beyond mammography is indicated. This

may include cytology of the discharge, galactography, MRI, ductoscopy, or duct excision. Cytology has shown variable results with a sensitivity ranging from 11% to 31% (10,11). Therefore, the presence of negative cytology does not confirm that an intraductal malignancy is not present. Galactography is the only method to determine preoperatively the nature, location, and extent of the lesion producing the discharge, and it allows for more precise and limited surgical excision of the area of abnormality. Galactography was first described in the 1930s (12,13) but was not commonly used until mammography became established. If a duct excision without a prior contrast study is performed, the surgery may be unnecessary or more extensive than needed. Also, a blind duct excision has the potential to miss an intraductal lesion in a small peripheral duct. As many as 40% of ductal tumors have been found to lie in a nonsubareolar location, which may cause a lesion to be missed at surgery if a duct excision without preoperative galactography is performed (14).

may include cytology of the discharge, galactography, MRI, ductoscopy, or duct excision. Cytology has shown variable results with a sensitivity ranging from 11% to 31% (10,11). Therefore, the presence of negative cytology does not confirm that an intraductal malignancy is not present. Galactography is the only method to determine preoperatively the nature, location, and extent of the lesion producing the discharge, and it allows for more precise and limited surgical excision of the area of abnormality. Galactography was first described in the 1930s (12,13) but was not commonly used until mammography became established. If a duct excision without a prior contrast study is performed, the surgery may be unnecessary or more extensive than needed. Also, a blind duct excision has the potential to miss an intraductal lesion in a small peripheral duct. As many as 40% of ductal tumors have been found to lie in a nonsubareolar location, which may cause a lesion to be missed at surgery if a duct excision without preoperative galactography is performed (14).

TABLE 14.1 Etiologies of Nipple Discharge | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The sensitivity of galactography has been studied by several authors (11,15,16). In a comparison of galactography and exfoliative cytology, Dinkel et al. (11) found the sensitivities for malignancy for each procedure to be 83% and 31.2% and the specificities to be 41% and 99%, respectively. The authors (11) found that one half of the cancers in the study demonstrated no palpable, mammographic, or cytologic abnormality and were identified only by galactography.

Van Zee et al. (17) found that localizing the lesion causing nipple discharge by preoperative galactography increased the likelihood that a specific pathology was found at surgery. In this study, 67% of patients who did not undergo galactography preoperatively did not have a specific pathology on excision. Cardenosa (18) found that galactography was positive in 32 of 35 (91%) of patients with spontaneous nipple discharge. In another study, however, King et al. (19) suggested that patients with nipple discharge should have breast imaging, and if this is negative, should be offered duct excision. The authors found no role for ductography, cytology, or laboratory studies. Dawes et al. (20) found that in 91 women with nipple discharge, only 5% were due to cancers and that galactography did not confirm or refute the presence of an intraductal lesion.

Galactography

Galactography is a contrast study that outlines the intraductal lumina. The purpose of galactography is to identify the presence and location of an intraductal lesion. The indication for galactography is the presence of a suspicious type of nipple discharge—that is, a spontaneous, uniorificial, serous, serosanguinous, or bloody discharge. Galactography depicts the course of the ducts and the location and extent of intraductal lesions. Preoperative galactography facilitates a more directed surgery and can avert unnecessary surgery when findings are benign (21).

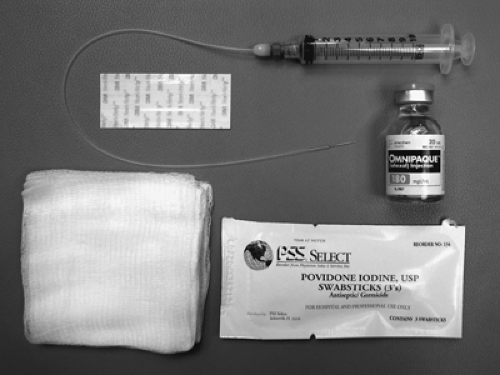

Galactography is performed only when discharge is present. The breast interventionist must visualize the orifice from which the discharge is occurring in order to cannulate the correct duct. The discharge is expressed, and the orifice is visualized. Identifying a trigger point is helpful to determine the orientation of the duct (7) before attempting duct cannulation. The supplies for the procedure include a 27- to 30-g cannula with tubing, a 5-cc syringe, water-soluble contrast, sterile gauze, antiseptic solution, and Steristrips (Fig. 14.1).

The nipple areolar complex is cleansed with an antiseptic solution, and the breast is draped. Small amounts of discharge are expressed from the breast until the orifice of the duct is identified. A blunt cannula—such as a 27-gauge pediatric sialography cannula with a straight end, a right angle, or an olive tip—is filled with water-soluble radiographic contrast. It is important to remove any air bubbles from the catheter, because when injected, they

may simulate intraductal masses. The duct is cannulated, and a small amount of contrast is injected. The most difficult step is cannulation of the duct, particularly if it is not dilated. Very gentle placement of the cannula is necessary to avoid penetration of the duct wall and extravasation of contrast. The cannula is taped in place with Steristrips. The amount of contrast needed ranges from 0.1 to 3.0 cc and varies with the number of secondary ducts draining into the main lactiferous duct and the degree of dilatation.

may simulate intraductal masses. The duct is cannulated, and a small amount of contrast is injected. The most difficult step is cannulation of the duct, particularly if it is not dilated. Very gentle placement of the cannula is necessary to avoid penetration of the duct wall and extravasation of contrast. The cannula is taped in place with Steristrips. The amount of contrast needed ranges from 0.1 to 3.0 cc and varies with the number of secondary ducts draining into the main lactiferous duct and the degree of dilatation.

Figure 14.1 Supplies for galactography: cannula, syringe, water-soluble contrast, antiseptic solution, Steristrips, and sterile gauze. |

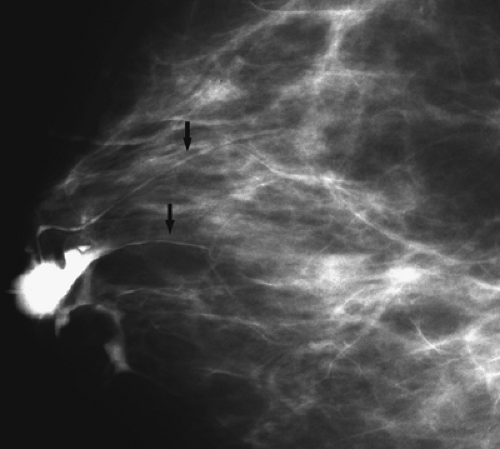

As the contrast is injected, the patient is asked to state when she feels tightness or pressure in the breast. At this point, the injection is terminated, the cannula is left in place, and images are obtained with mild compression. Should the patient experience pain, indicating possible extravasation of contrast, injection should be terminated immediately. The patient is positioned at the mammographic unit, and the craniocaudal (CC) view is obtained. If duct filling is incomplete, more contrast may be injected, and the CC view is repeated. With an obstruction of the distal duct, rapid backflow of contrast occurs.

Routine images include CC and mediolateral (ML) views. Magnification views are often helpful in the observation of small filling defects (21), and digital imaging is helpful to expedite the study. At the completion of imaging, the catheter is withdrawn with the breast still in compression, and a final image of the distal aspect of the duct is made. After the procedure, the patient is asked to express the residual contrast from the breast.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree