Abstract

Standard breast preservation techniques often fail to achieve the desired goal of complete tumor extirpation with adequate margins while preserving breast cosmesis. The emergence of oncoplastic breast surgery addresses these limitations and allows breast conservation in women who would not otherwise have met traditional criteria. Oncoplastic surgery combines sound surgical oncologic principles with plastic surgery techniques and requires a multidisciplinary approach and thorough preoperative planning. Using these techniques, tumors can be successfully resected from any quadrant of the breast while maintaining or improving breast cosmesis, diminishing postradiation deformities, and providing breast symmetry. Oncoplastic surgery requires a philosophy that the appearance of the breast after breast cancer surgery is important.

Keywords

oncoplastic surgery, breast surgery, breast conservation, breast cancer, reduction excision

The adoption of breast conserving therapy as an acceptable alternative to mastectomy opened the door to a wide and varied range of partial breast reconstruction techniques. The term oncoplastic breast surgery, as suggested by Werner Audretsch in 1993, describes the concept of local tissue rearrangement that would allow for wide resection of tumors while preserving or improving breast cosmesis. Although the term has been used more broadly to include nipple- and skin-sparing mastectomies with immediate reconstruction, this chapter focuses on immediate or delayed partial breast reconstruction with volume-displacing or volume-replacing techniques after wide excision of the primary lesion. In other words, oncoplastic breast conservation. A contralateral mammaplasty or mastopexy is generally required for symmetry due to the loss of volume from removal of the index cancer.

Traditionally, surgical oncologists are trained to remove the cancer at all costs, with little emphasis placed on the importance of the cosmetic result. Many women have simple excisions and appear to have a reasonable cosmetic outcome in the early postoperative period, but the early results are sometimes misleading. The addition of scarring, resolution of the seroma, and radiotherapy ultimately reveals the true esthetic outcome many months or even years later.

Oncoplastic breast conservation surgery is a new paradigm combining sound oncologic principles with plastic surgery techniques, allowing for wide excision of tumors with minimized risk of involved margins and simultaneous prevention of the deformities commonly associated with simple excisions and postradiotherapy fibrosis. It requires a philosophy that the appearance and function of the breast after tumor excision is important; the patient will live with this result for the rest of her life. The goals of oncoplastic breast surgery include complete removal of the lesion with negative margins, a good to excellent cosmetic result, and the definitive procedure at a single operation. Over the past 30 years we have developed a comprehensive multidisciplinary oncoplastic approach for the surgical treatment of breast cancer. This requires an approach that includes coordination with the surgical oncologist, radiologist, plastic surgeon, medical oncologist, pathologist, radiation oncologist, and genetic counselor. As improved breast imaging and neoadjuvant chemotherapy allow a larger number of women to be considered for breast conservation, the combination of oncologic and plastic surgery disciplines also increases the number of women who may be treated with breast conserving surgery by allowing larger excisions with more acceptable cosmetic results. These techniques are applicable to patients with both noninvasive (ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS]) and invasive breast cancers. Furthermore, now that excision without radiation therapy is an accepted treatment for patients with biologically favorable DCIS, widely clear margins are of even greater importance than previously appreciated.

An important goal in caring for a woman with breast cancer is to go to the operating room once and perform a definitive procedure that does not require reoperation. The first attempt to remove a cancer is critical, offering the best chance to remove the entire lesion in a single piece, evaluate its true extent and margin status, and to achieve the best possible cosmetic result. The concept of a one-stage operation is important in the psychological and emotional recovery of a cancer patient. Fewer procedures allow the patient to quickly move on with her life, to the next phase of treatment, if necessary. With this in mind, it is of highest importance to thoroughly stage the cancer preoperatively and carefully plan the operation. This is accomplished by reviewing the patient’s full diagnosis, stage, pathology, imaging, risk of recurrence, and risk of developing cancer in the contralateral breast. Whenever possible, the initial breast biopsy should be performed using a minimally invasive percutaneous technique. This usually provides ample tissue for diagnosis and biomarker analysis and should be possible in more than 98% of cases. Preoperative knowledge of tumor biology can sometimes be exploited by using neoadjuvant systemic therapy, which will often downstage a tumor and convert the definitive operation from mastectomy to breast preservation.

General Considerations

Leading the Oncoplastic Team

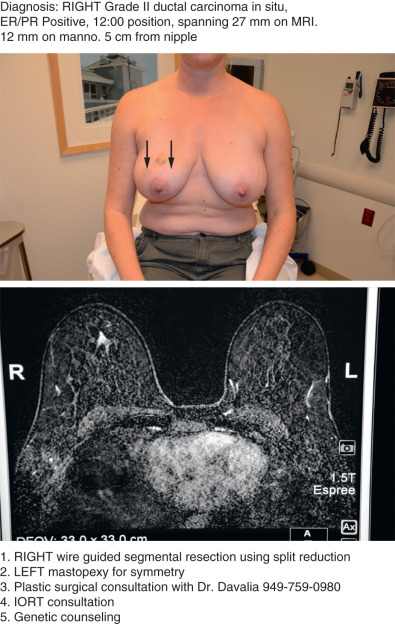

Of utmost importance is a dedicated team approach. At our facility, the oncologic breast surgeon assumes the role of “leader” to guide the team and ensure excellent communication among all team members. During the first visit we generate a “flight plan” that summarizes the diagnosis, includes photos of the patient’s chest and relevant imaging, and lists the plan of action leading up to and including the planned operation ( Fig. 40.1 ). The flight plan is given to the patient, distributed to all team members, and updated and revised, if necessary, as the patient moves through the consultation process.

Rationale for Oncoplastic Breast Surgery

The primary goal of breast conservation is to achieve local control with adequate margins while maintaining breast cosmesis. Unfortunately, as many as 36% of simple excisions fail to achieve adequate margins in a single operation, leading to reexcision, worsening cosmesis, and conversions to mastectomy. The benefits of breast conservation compared with mastectomy are preservation of a sense of wholeness, retaining normal breast sensation, and limited morbidity from device-based or autologous reconstruction. The benefits are even greater when adjuvant radiotherapy must be added to postmastectomy reconstruction.

A few of the factors implicated in poor cosmetic results after breast conservation are age greater than 60, tumors larger than 2 cm, small breast size, reexcision for inadequate margins, improper scar orientation, breast tissue resection greater than 100 cm 3 independent of breast size, breast ptosis, tumors located in the central, medial, or lower quadrants, and radiation dose inhomogeneity. The common theme among all these limitations is that the removal of tissue without proper reshaping of the breast allows scarring and postradiation fibrosis to reveal an unreconstructed cavity, imbalance in breast tissue distribution, and distortion of the nipple-areola complex (NAC). These limiting factors are largely overcome when an oncoplastic reconstruction is performed. Oncoplastic breast conservation allows rebalancing of the breast. The breast is reconstructed with either a volume displacing or volume replacing technique. This ability to maintain breast balance while reducing breast volume expands the pool of patients who could be considered candidates for breast conservation. This is of particular benefit to the patient with advanced disease who would need adjuvant radiotherapy regardless of mastectomy. These techniques are referred to as extreme oncoplasty or radical breast conservation and are discussed later in this chapter.

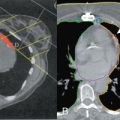

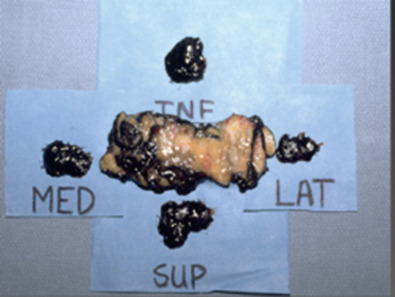

Currently, because many as 40% to 50% of new breast cancer cases are discovered by modern state-of-the-art imaging. Intraoperatively they are often grossly both nonpalpable and not visible to the surgeon’s eye. Under these circumstances, the surgeon essentially operates blindly. Multiple hooked wires can help define the extent of the lesion and guide surgical excision. Using bracketing wires or other newer forms of localization, the surgeon can usually excise the entire lesion within a single piece of tissue, sometimes including overlying skin as well as prepectoral fascia as the anterior and posterior margins. The tissue should be precisely oriented for the pathologist. Intraoperative two-view specimen radiography is extremely useful in localizing the lesion within the specimen, estimating margin distance, and ensuring complete removal.

If the specimen is removed in multiple pieces, rather than a single piece, accurate size and margin assessment may be compromised. Fig. 40.2 shows an excision specimen with four additional pieces that represent the new margins, but clearly the additional specimens do not encompass the full margin, leading to uncertainty about complete excision.

Reconstructive Goals

A common misconception is that the goal of breast reconstruction is to create the “perfect breast.” In actuality, the goal should be to achieve an outcome that best suits the patient’s goals for treatment and desires for final breast appearance. The patient’s esthetic goals are often tempered by the complexity of many of the most modern and technically state-of-the-art reconstructive methods. In the same vein, the default reconstructive goal should not be to simply maintain the patient’s current appearance. With this in mind, the reconstructive plan can be formulated only after analysis of the tumor size and location, the preoperative breast shape, size, and degree of ptosis, and understanding the patient’s oncologic needs and reconstructive desires. The ideal is to minimize the amount of surgery, donor sites, recovery periods, risk of complications, and failure rates, while maximizing the desired esthetic and oncologic outcome.

Many reconstructive options exist, ranging from a simple tissue rearrangement to complex microvascular tissue flap reconstruction. Each step toward a more complex procedure must be carefully weighed against the patient’s expectation of results and assessment of the risk to benefit ratio. Reconstructive surgeons may be tempted to use all of their advanced skills and create a complex surgical plan with multiple operations. However, the patient may be satisfied with the reasonable breast shape and symmetry achieved with a simpler course. The decision must be an amalgam of what is oncologically necessary and the simplest reconstructive plan that achieves the patient’s goal. Our goal has always been to go to the operating room once, completing the oncologic and reconstructive portions of the case in a single procedure, if possible. The decision to use volume displacement techniques (in other words, to use existing breast volume to reconstruct the defect, versus volume replacement techniques that use regional or distant tissue flaps of varying complexity) depends on the reconstructive needs. Volume displacement techniques offer the simplest solution when there is adequate native breast tissue and the patient accepts a smaller reconstructed breast as well as the need for contralateral surgery to correct asymmetry. Volume replacement allows maintenance of the preoperative breast size but often requires longer operative time, longer recovery, and has associated donor-site morbidity. Our practice is devoted primarily to volume displacement reconstruction and defers to mastectomy only when this is not feasible. In other words, mastectomy (although sometimes appropriate and necessary) is our last choice and never our default option.

To help patients understand the value of oncoplastic breast conservation, they must be educated about their options and the rationale for patient selection and merits of simple excision versus oncoplastic breast conservation. For surgeons, the ability to predict the postlumpectomy deformity leads to understanding the importance of patient selection.

Women with smaller breasts (A/B cup) and minimal ptosis can be challenging. Simple excisions of small tumors are often believed to have little esthetic effect. This is often true when the tumor is in the upper or upper outer breast and a layered glandular repair is performed. However, even the smallest tumor can result in a postlumpectomy deformity if excised from the lower pole of the breast. Postoperative scarring will deform the lower pole and retraction will displace the NAC inferiorly, resulting in the classic “bird’s beak” deformity ( Fig. 40.3 ). This can be avoided by recentralizing the NAC over the reshaped breast mound immediately after the resection. With larger tumors, a prediction about the size of the defect will determine eligibility for breast conservation. If the predicted remaining breast is deemed adequate for reconstruction with glandular rearrangement, then oncoplastic breast surgery can be planned. However, if these predictions are inaccurate, then a post lumpectomy deformity will result. In retrospect, these patients may have been better managed with volume replacement techniques or with skin- or nipple-sparing mastectomy. These missteps can only be avoided with experience, and the novice oncoplastic surgeon should be wary.

Women with larger breasts (C/D cup and beyond) and ptosis will benefit from oncoplastic breast surgery both oncologically and esthetically. An oncoplastic approach will allow a larger excision with higher probability of obtaining adequate margins as well as correction of breast ptosis and macromastia. Furthermore, the correction of macromastia yields the benefit of better adjuvant radiotherapy dose homogeneity with resultant long-term maintenance of cosmesis.

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative planning requires discussion among, at a minimum, the oncologic surgeon and the radiologist. Usually a plastic surgeon, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, and others should be included as well. All of the preoperative tests must be carefully evaluated and integrated with information about the pathologic subtype, size and extent of the lesion, size of the breast, lesion position within the breast, patient wishes, among other concerns. Other particular concerns include invasive lobular cancers that may be larger than expected based on initial imaging, extensive in situ components with similar risk for underestimation on imaging, patient desire for symmetry, and timing of the symmetrizing procedure.

Various options for the timing of oncoplastic breast surgery have been suggested.

- •

Immediate: Definitive oncoplastic breast surgery at the time of tumor resection. This is a single-stage approach that has the advantage of using surgically naive tissue for reconstruction but may require repeat operations if margins are not clear and may necessitate mastectomy if the proper margins cannot be identified at reexcision.

- •

Delayed-immediate: Delay of oncoplastic breast surgery until final pathologic margins are confirmed to be clear, usually one to 3 weeks later and before the delivery of radiotherapy. This is a staged approach that has the advantage of definitively clearing the margins before committing to oncoplastic breast surgery but the downside of requiring multiple operations.

- •

Delayed: No oncoplastic breast surgery until after completion of adjuvant systemic and radiation therapy, usually 1 to 2 years later. This has the advantage of minimizing the potential delay of initiation of adjuvant therapy from wound-healing complications, but has the highest complication rates and least favorable esthetic outcomes.

In our practice, we have evaluated our postoperative margin status after initial surgery, specifically comparing simple elliptical excisions and Wise-pattern mammaplasty excisions. For tumors spanning 50 mm or more, the elliptical excision group (n = 250) had negative margins (defined as no ink on tumor in 88% of cases. The oncoplastic reduction group (n = 300) had negative margins in 97% of cases. For tumors spanning more than 50 mm in the extreme oncoplastic group (n = 125), the negative margin rate was 87%. As such, we feel justified in routinely performing immediate oncoplastic breast conservation in virtually all patients who are candidates for breast conservation. Even for tumors larger than 50 mm, the positive margin rate is similar to that of simple excisions with margin shaving. In the case of positive margins, early reexcision before scarring has obliterated the dissected planes allows re-creation of the excisional defect for more accurate reexcision. When conversion to mastectomy is indicated, it is of benefit for the macromastia patient to have had the preliminary skin reduction and NAC repositioning. This patient who, before this failed oncoplastic breast conservation, may not have been a good candidate for NAC-sparing mastectomy may now successfully have the procedure after allowing 1 to 2 months of healing for revascularization of the NAC.

The skin overlying the tumor does not always need to be removed as a rule. However, when skin is not removed the anterior margin may be close or involved. We always measure skin-to-tumor distance using all three imaging modalities (mammography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging). If the skin-to-tumor distance is less than 10 mm, we remove the overlying skin. For patients with DCIS in whom we do not plan to irradiate postoperatively, we generally remove the overlying skin to ensure a negative anterior margin.

It is expected that oncoplastic resection of the index tumor will result in asymmetry. Given that breast asymmetry after breast conservation is known to affect psychosocial functioning and quality of life, the value of contralateral symmetry surgery is not debated. The ideal timing for surgery of the contralateral breast would be after the index breast has been treated and adjuvant radiotherapy has been delivered. It is well accepted that the index breast will respond to radiotherapy with a variable degree of volume loss, fibrosis, and loss of elasticity. At a second operation the contralateral breast can be reduced and lifted for symmetry after these postradiotherapy changes have stabilized. Although ideal symmetry can be achieved in this staged approach, the index breast may continue to slowly shrink for years due to ongoing radiation injury.

When presented with the option of having two separate operations over the span of 1 to 2 years versus having both operations performed in the same setting, albeit with somewhat less accurate symmetry, it is rare that a patient prefers a staged approach. Virtually all are willing to accept the lesser symmetry from a single-stage approach when educated about the long-term effects of radiation therapy. With that in mind, a small fraction of our patients do return 3 to 4 years after surgery to have a secondary procedure for the contralateral breast to maintain symmetry.

Surgical Considerations

On the day of surgery, the patient undergoes wire localization (we do this the afternoon before surgery if the operation is scheduled as a first-start case) and sentinel node mapping by the radiologist. Just before surgery, generally in the preoperative holding area, she is marked in the upright position and counseled one final time. In the operating room, she is positioned on the operating table with her arms secured to the arm boards at 90 degrees. This allows for the head of the bed to be raised 45 to 90 degrees during the operation to assess symmetry. Assuming a bilateral procedure is planned, a two-team approach is used. While the oncologic surgeon is resecting the tumor from the index breast, the plastic surgeon is performing the contralateral breast symmetry procedure. After the tumor has been resected, the index breast is reconstructed, thus minimizing any increase in operative time. Drains are generally not required for these operations. At the conclusion of the procedure, the patient’s breasts are wrapped in a compressive dressing for 24 to 48 hours to minimize seroma, ecchymosis, and hematoma.

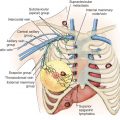

With the range of oncoplastic approaches, precise and thorough communication between the plastic surgeon and oncologic surgeon is crucial. Proper preoperative planning, combined with knowledge of the blood supply of the breast, will usually allow preservation of a robust pedicle for the NAC and minimize necrosis.

Oncoplastic Techniques

Simple Glandular Flap Techniques

Glandular rearrangement can range from basic undermining and closure of a defect to tissue rearrangement with glandular flaps. The basic technique is to achieve closure of the parenchymal defect independent of the skin. An incision is made for access, often within the periareolar border, but can be anywhere on the breast. Through this incision, skin flaps are elevated (akin to mastectomy flaps) to expose the involved region of the breast. Once the excision is complete the adjacent parenchyma is freed from the underlying chest wall fascia. At this point, if primary closure of the defect is possible without deforming the breast, then it is performed with interrupted sutures. If primary closure is not possible, then the parenchyma can be further freed both from the overlying skin and underlying fascia. Care must be taken to preserve an adequate blood supply. This technique should be avoided in a predominantly fatty breast to avoid fat necrosis. The mobilized flaps of glandular tissue from both sides of the defect can then be rotated or advanced into the defect and sutured into place. Any dimpling of the overlying skin should be conservatively undermined before skin closure ( Fig. 40.4 ).