Key points

- •

The treatment of colorectal cancer, metastatic to liver, should be optimally managed within the context of a multidisciplinary team to improve patient-centered outcomes.

- •

Treatment intent should be categorized as ““curative,” “potentially curative,” “noncurative for active therapy” (the majority) and “noncurative for palliation” of symptoms (best supportive care).

- •

Increasing options for combined modality approaches require a treatment pathway and strategy, both at the outset (first presentation), and repeatedly if necessary as the clinical course progresses.

- •

Access to new modalities and evolving treatments will advance the effectiveness of the team

Introduction: Multidisciplinary team approach

The diagnosis, staging, and treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC), as well as the management of potential medical and psychological complications, requires a multidisciplinary or team approach. Throughout a patient’s cancer journey, the central tenet for the team is providing continuous optimal care from all aspects, of a typically incurable condition. Evidence-based medicine provides changing guidelines for the benefit, almost exclusively, of a single intervention in the context of controlled clinical trials, where patients fit very selective, often rigorous, criteria. However, the real-life challenges are significantly more complex and more commonplace as the whole colorectal cancer patient population encompasses a broader and more multifaceted spectrum and invariably need multiple interventions at various levels of evidence. In reality the impact of potential toxicities of sequential treatments and impact on quality of life are rarely disclosed within the published literature. The challenge is therefore for each patient to be analyzed systematically by the colorectal multidisciplinary team, and then to use a contemporaneous evidenced-based approach to justify and facilitate a sequence of clinical interventions. Patients should be made aware and be offered choices, where options are available, as there is often a limited impact of treatments on quantity of life and the potential effects on the quality of life. An independent patient-linked advocate, which is usually an “advanced nurse practitioner” (ANP) or a “clinical nurse specialist’ (CNS), helps immensely, in what is a terrifying situation for patients and their famili es.

The role of complex liver interventions and surgery for colorectal liver metastases is discussed later in this chapter and is one of the specific areas where the prospective planned management of colorectal cancer patients is changing rapidly. It may have a major, potentially curative, impact on some patients and may also contribute to prolonging survival in as many as 20% of patients presenting with, or relapsing with, metastatic disease.

Epidemiology and staging

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in developed nations. There are approximately 1,000,000 cases per year globally with more than half a million deaths. There is a wide geographical global incidence range, with most Western countries at 20–40 per 100,000 population. Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in the United States, with more than 100,000 cases of colorectal cancer diagnosed. Colon cancer affects both sexes with approximately equal frequency; however, tumors in the rectum appear more commonly in men at a ratio of 1.5:1 to women. Colorectal cancer incidence is gradually decreasing in western countries. The probability of developing colorectal cancer rises sharply with age, with 83% of all cases arising in people who are 60 years or older and median age at diagnosis over 70 years. The lifetime risk for men of colorectal cancer is estimated to be 1 in 18, and 1 in 20 for women.

The overall survival (mortality) is stage-specific, with the 5-year overall mortality decreasing incrementally over the last 30 years. This is due to the synergy between individual advances in diagnostics, surgery, and oncology. The overall 5-year survival of all CRC cases in Western countries ranges from 52% to 65%. A total of 80%–85% of patients with colon cancer have some symptoms at the time of diagnosis. At disease presentation, around 55% of people have advanced cancer that has either spread to lymph nodes or other organs, or is so locally advanced that surgery is unlikely to be curative (stage III or IV or Dukes’ C or D). More advanced stages of local and distant spread correlate inversely with survival; however, positive anomalies have now appeared, because of improvements in advanced colorectal cancer management. The first example is with the advent of adjuvant chemotherapy, in that the prognostic outcomes of substages of II and III now overlap: Stage IIa and stage IIIa have similar survival rates, with stage IIb (T4N0) actually having significantly worse outcomes compared to stage IIIa.

The second example is more recent, and is almost certainly attributable to successful liver surgery for limited CRC metastases. The prognostic outcomes of substages of III and IV now also overlap in that the worse subsets of stage III and best of stage IV (limited surgically operable metastases) have similar survival rates. The staging systems are thus only tools in assessment but increasingly are understood to be one of many factors that influence outcomes. Increasingly, patient-related clinical factors and biolog parameters, including chemosensitivity and genetic profiles, often outweigh the impact of staging both adversely and favorably, in ways that we as yet cannot predicate.

Tissue diagnosis is mandatory in all cases, unless the patient is not fit for any treatment interventions. Modern centers now add immediate genetic testing for somatic mutations, as these have major implications for systemic treatment options, both from a predictive and prognostic point of view. At a minimum, KRAS and BRAF testing should be done at the outset, in all metastatic cases. Many centers have moved to multigene testing systems, as small subsets of cancers have “druggable” mutations with targeted therapies that are already available.

A strong family history or multiple recurrent polyps should invoke potential discussions about family, genetic, and mutation testing with qualified geneticists and counselors. A detailed discussion on this subject is beyond the scope of this chapter.

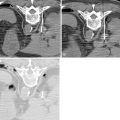

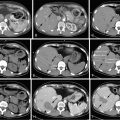

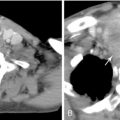

Staging is mandatory prior to discussion on treatment planning. A minimum of a modern high-quality computed tomography (CT) scan of chest/abdomen and pelvis should be performed in a patient with confirmed cancer. The focus of the radiology should be to look specifically at common sites and patterns of spread of colon cancer: (in descending order) liver, peritoneum, lung and distant lymph nodes. Note that in contrast to the other common adenocarcinomas (i.e., breast, lung, and prostate), bone, spinal cord and brain, and CRC metastases are uncommon and occur in less than 5% of metastatic patients at presentation.

Additional radiologic tests are extremely useful in rectal cancer for planning management. An MRI of the pelvis in rectal tumors is used to assess whether primary surgical curative removal is potentially feasible and whether any neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is warranted to try and improve local control and overall outcomes. Modern evidence suggests that MRI is better than CT for local staging of primary rectal cancer, particularly in assessing unresectable disease (or “threatened margins”) and identification of cancer-positive lymph nodes. There is, however, wide variability between results reported in different studies and, which highlights the need for dedicated and trained site-specific radiologists to minimize the false-negative and false-positive rates of determining involved lymph nodes. In a phase II prospective series (MERCURY) of 712 patients, the correlation between MRI and pathologic staging after surgery alone was 0.92, with an observed agreement of 84% (kappa 0.49, 95% CI: 0.35–0.61) between the MERCURY assessment of prognosis and pathology findings after primary surgery.

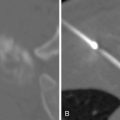

In situations where liver or lung surgery (metastatectomy) is contemplated, dual, triple, or even quadruple imaging modalities are often necessary. Liver MRI, liver ultrasonography (preferably with contrast enhancement with microbubbles) and F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography ( F-FDG-PET) scanning are often complimentary to a CT. F-FDG-PET is particularly useful in detecting occult extrahepatic disease. Because of the difficulty in localizing structures with an F-FDG-PET, this investigation is always performed in conjunction with a separate CT contrast-enhanced scan, despite dual-modality combination advances (CT-PET, which do not have the same specificity or sensitivity for liver imaging).

Although blood tests are frequently nonspecific, they can impart useful information for treatment planning and prognostication. For example, a low serum albumin, high alkaline phosphatase, and high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level and possibly high neutrophil and platelet counts are poor prognostic factors. In advanced disease, the liver and renal function can significantly alter the choice or doses of chemotherapeutic agents or interventional therapy that can be offered safely.

Specific tumor markers for colorectal cancer have become commonplace through their clinical utility. About two-thirds of CRC are associated with an elevated serum CEA (carcino-embryonic antigen). This and the serum CA19.9 antigen can be very useful tools in monitoring treatment response in conjunction with other modalities such as radiology. In isolation, they have low specificity and so always need validation with imaging to confirm their trend. A crucial learning point is that tumor markers are not validated to confirm changes in treatment pathway decisions and are not allowable in regulatory clinical trials as valid end points of response or progression.

Systemic chemotherapy

In deciding treatment options, the primary question is whether the patient has a technically or potentially curable malignancy. The secondary and equally important point is whether it is clinically appropriate for the patient to be subject to this potentially curative approach.

The only clear level 1, curative modality is resection. All other modalities of treatment can add or accentuate the benefit of resection, but are rarely curative in their own right. Resection of the primary colonic or rectal tumor is the principal first-line treatment in the majority of colorectal cancer patients. However, in the context of advanced metastatic disease, it is noncurative and predominantly performed for palliation of symptoms alone. In more recent practice, and with the improvement of systemic chemotherapy tumor response rates, the frequency of the first intervention being primary colorectal surgery is decreasing and is as low as 60% now in contemporaneous clinical studies. When curative resection is not possible, patients may benefit from palliative resection, which is becoming increasingly minimally invasive, and more alternatives such as endoluminal stenting to relieve partial or subacute obstruction are now available as means to expedite the systemic treatment.

Indeed, a risk of attempting primary surgery first is significant delay in starting treatment in metastatic disease, which is the usual cause of constitutional deterioration in advanced patients and ultimately responsible for deaths.

High-quality surgery is thus crucial to patients’ survival, and the surgical outcomes are the platform of overall success of the MDT. Hence, specialist colorectal cancer surgeons should be able to demonstrate low tumor involvement at the margins of the excised cancer specimens, low rates of surgical complications, and high survival rates among their patients. If surgery is not the planned primary modality, a rediscussion at various time points, should ensue, as to whether there is an appropriate treatment window, and where it can be integrated without significant disturbance to the systemic objectives. There is mounting retrospective evidence that, even in systemic disease, a strategy to remove the primary tumor adds to the improved survival of that patient. Another major advantage of early removal of the primary tumor is the accurate locoregional tumor staging, especially the identification of involved lymph nodes and presence of lymphovascular invasion or T4 local disease. These features are crucial for patient prognosis and thus management for two reasons. First, residual involved lymph nodes after surgery can precipitate local recurrence (especially in rectal cancer). Second, decision making on the need for adjuvant chemotherapy depends on the pathologic stage of the cancer. Chemotherapy offers proven survival benefit (level 1 evidence) for those with stage III tumors. There is some evidence for benefits also in high-risk stage II tumors with features of lymphovascular invasion, emergency presentations with obstruction or perforation, poorly differentiated and T4N0 tumors. Three variables contribute to the yield of lymph nodes: the aggressiveness of surgery, the diligence of the pathologist in searching the specimen, and the anatomy of the patient and the tumor. Evidence shows that when more nodes are pathologically examined (at least 12), tumors are significantly more likely to be classified as node-positive. The implication for patients with limited colorectal liver metastases is that this may influence the timing and sequence of when to integrate systemic chemotherapy. A heavily node-positive pathology (in relation to the primary site) implies that the attempted adjuvant eradication of extrahepatic micrometastatic disease weighs just as heavily in the decision-making process as eradication of the liver metastases, and both concepts need to be integrated in the MDT planning process.

Over the last 35 years, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)–based adjuvant therapy has become the mainstay of treatment for patients with Dukes C or stage III colon cancer. The standard treatment has been a course of 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid (FUFA), given intravenously (IV) over 6 months. Pooled data from seven randomized controlled trials in patients with stage II or III colon cancer suggest that 5-FU/FA regimens increase disease-free survival at 5 years from 55% to 67% and overall survival from 64% to 71% when compared to surgical resection alone. The potential benefits and risks of chemotherapy should be discussed with patients for whom it is judged appropriate, so that they can make an informed choice. Adjuvant chemotherapy should be scheduled to begin within 6–8 weeks postsurgery. The MOSAIC study was the first trial to show a statistically significant disease-free survival benefit for a treatment regimen other than 5-FU for stage III colon cancer in the adjuvant setting. At 4 years, there was a 25% reduction in the risk of disease recurrence in these patients for the combination oxaliplatin/5-FU/FA compared with 5-FU/FA alone ( P = 0.002). The place of chemotherapy in the treatment of patients with Dukes stage B cancer must be a matter for discussion between patients and their oncologists, as the benefits in some groups are small. The QUASAR1 trial and MOSAIC both showed statistically significant risk reductions in those treated compared to the control arms of no-treatment (best supportive care) and the addition of oxaliplatin to 5-FU, respectively. The survival benefit for patients with rectal cancer is believed to be similar, although the evidence is much weaker, and often confounded by the need to give chemoradiotherapy.

Distinctive considerations for metastatic rectal cancer

The decision-making process for primary rectal cancer with metastases, especially if the primary is locally advanced, as is usually the case, is more complex as the overall disease-free survival outcomes are worse, the surgery potentially more complex, “disfiguring” (e.g., requiring a stoma), and functional bladder, sexual, and bowel outcomes have a high impact on the quality of the (frequently limited) remaining life of the patient. On the other hand, local rectal recurrences can lead to serious morbidity (severe pain, fistulae, and obstruction leading to death). Total mesorectal excision (TME) is a technique that involves meticulous mobilization, followed by either colo-anal anastomosis or completion as an abdominoperineal anorectal excision, is the standard of surgery for cancers of the middle and distal thirds of the rectum. TME is associated with about half the rate of local recurrence, compared with previous techniques in the lower two-thirds of the rectum. In rectal cancer, because of the high risk, and associated morbidity, of local recurrence, radiotherapy can play an important part in the overall management of the patient to specifically reduce this risk.

Pelvic radiotherapy in primary rectal cancer is now considered as a standard primary modality treatment option. This can be as adjuvant or (increasingly) neoadjuvant, prior to surgery. In the advanced metastatic patient, its role has to be carefully planned as it is often integrated with systemic chemotherapy approaches, to aim to control both distant metastases and locoregional disease simultaneously.

In the Swedish randomized preoperative radiotherapy controlled trial, patients in the treatment arm assessed their bowel movement as “excellent,” compared with 32% of 87 patients who had had surgery alone. Seven percent of the irradiated group, but none of the controls, rated their bowel function as “bad.” Nearly 50% of those in the irradiated group had to use fecal incontinence pads, compared with 22% in the control group. Other problems, such as urgency of defecation and loss of skin on the perineum, were also significantly more troublesome in irradiated patients.

Advances in chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer

After over 40 years of frustratingly slow progress, with only 5-FU (usually given with leucovorin/folinic acid; LV), as the mainstay of treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), the last 10 years have been remarkable because of the realization of four new active agents of different biologic mechanisms of action, which have incrementally improved response rates and overall survival over and above 5-FU and best supportive care (BSC) alone. In 2012 alone, two further active agents were identified as part of the potential chemotherapy armament in the routine “standard of care,” with level-one evidence. Thus, the median overall survival in incurable mCRC has improved from 9 to 12 months with 5-FU/LV monotherapy in the 1980s to near 22–24 months currently. The number of patients living 5 years (with or without disease) in stage IV has also gradually increased to around 10%.

The chemotherapeutic agents, irinotecan and oxaliplatin, now form part of the “doublet” chemotherapy approach (with 5-FU/LV) in the majority of patients worldwide. Two targeted biologic agents that are more cancer specific, with less conventional toxicity profiles, are also used additionally (although limited in some countries because of their high cost). These are an anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) monoclonal antibody (mAb), bevacizumab, and the human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER-1 or EGFR) targeted mAb, cetuximab. In addition, patient convenience is also improving as the fluoropyrimidines that previously could only be given intravenously (5-FU/LV) can now also be delivered orally . However, as the number of agents and survival increase, choosing the most effective treatment strategy is becoming increasingly complex, uncertain, and progressively expensive. As more lines of therapy are being offered in palliative situations, and as monotherapy has moved to combinations and, more recently, to sequential combination therapy, cumulative toxicity profiles will influence choice, progressively more in palliative situations. Conversely, aggressive sequential approaches, also involving surgical or ablative metastasectomies in liver and lung, or locoregional approaches are desirable where cure may be attainable in individual presentations of mCRC.

The key chronologic developments in chemotherapy for mCRC based on randomized clinical trials contributing to the current general paradigms of treatment are summarized here:

- 1.

FU administered as a continuous intravenous (IV) infusion led to a significantly higher response rate and a better toxicity profile than bolus IV FU (Mayo protocol) (22% vs. 14%, respectively; OR = 0.55; P = 0.0002), although the median survival times were similar (infusional FU 12.1 months vs. bolus FU 11.3 months; HR = 0.88; P = 0.04). These conclusions are from a pooled analysis incorporating data from six randomized trials.

- 2.

FU activity is enhanced with the biochemical modulator folinic acid (leucovorin [LV]) confirmed by a meta-analysis of 3300 patients randomized in 19 trials (response rates 21% vs. 11%, respectively; P < 0.0001).

- 3.

Irinotecan, a topoisomerase I inhibitor, alone and in combination with FU/LV has survival benefit. Infusional FU combinations are significantly safer with higher efficacy, with diarrhea being the main adverse effect.

- 4.

Oxaliplatin is a cisplatin derivative, with significant activity only in combination with FU/LV. Phase III studies consistently show higher response rates, longer median progression-free survival (PFS), time to progression, and survival than those observed with FU/LV alone, but survival differences are not consistently statistically significant. There is a dose-dependent, mostly reversible, sensory neuropathy as a cumulative dose-limiting toxicity (increasing from about 800 mg/m ).

- 5.

Comparing first-line combination superiority between oxaliplatin and irinotecan is highly complex, and overall all the trials essentially show equivalence for survival. They reconfirm that bolus FU combinations have more toxicity, and that combining oxaliplatin and irinotecan together is not worthwhile without infusional FU. The largest trial (UK FOCUS study) gives confidence to clinicians who are familiar in detail with all the published evidence, that there are numerous choices in the chemotherapeutic options for all patients. Thus careful selection of individual treatment pathways for patients, based on the combined aims, comorbidty, and toxicity profile of the regimens, is achievable without compromising potential patient benefits. Trials sequencing the drugs in different ways again conclude that overall survival is no different, as long as patients have access to all three compounds at some stage. This was shown in a meta-analysis of seven phase III trials.

- 6.

The oral fluoropyrimidines capecitabine, UFT-tegafur, and S1 are established as being equivalent to IV 5-FU. The data for oral combinations with irinotecan and oxaliplatin is standard, although the toxicity profiles are different.

- 7.

Tumors cannot grow beyond 1–2 mm without the formation of a blood supply or angiogenesis. This also allows a pathway for tumor cells to seed into the systemic circulation and establish further metastases. The transition, or switch, of a tumor to an angiogenic phenotype is caused by an increase in proangiogenic factors, including VEGF, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β). VEGF is highly upregulated in most human tumors, including colorectal cancer. This has been correlated with increased tumor invasion, microvessel density, disease recurrence, and a poor prognosis. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy in the first- and second-line settings in patients with mCRC has significant activity. More than 900 patients were randomized to one of three treatments with bolus 5-FU: IFL/placebo, IFL/bevacizumab, or FU/LV/bevacizumab. The addition of bevacizumab to IFL resulted in a significantly increased response rate, duration of response, PFS, and improved overall survival by almost 5 months (20.3 months vs. 15.6 months; P < 0.001). For the subgroup of patients who received second-line therapy with oxaliplatin-containing regimens, overall survival times were 25.1 months and 22.2 months for the IFL/bevacizumab and IFL/placebo arms, respectively. There is now second-line survival benefit data with oxaliplatin-5-FU-bevacizumab combinations. Chemotherapy with bevacizumab is generally well tolerated, with no overlapping toxicities. Adverse events include bleeding, thrombosis, proteinuria, and hypertension, which are generally manageable. However, a low percentage of patients (∼2%) have serious gastrointestinal events, including bowel perforation. There also has to be caution with regard to healing following VEGF inhibitors (and chemotherapy), especially in complex multidisciplinary pathways requiring liver, vascular, or surgical intervention.

- 8.

The HER-1/EGFR signaling pathway is thought to play a pivotal role in tumor growth and progression of colorectal and other cancers where overexpression is correlated with disease progression, poor prognosis, and reduced sensitivity to chemotherapy. EGFR belongs to the HER family of receptors. These receptors are transmembrane glycoproteins, with an extracellular ligand-binding domain, and an intracellular tyrosine-kinase (TK) domain. Ligands that bind to the HER-1/EGFR extracellular domain induce receptor homo- or heterodimerization with other HER-1/EGFR receptor or family members. This results in activation of the receptor’s TK activity, initiating a downstream-signaling cascade that ultimately leads to tumor cell proliferation, migration, inhibition of apoptosis, and angiogenesis. Demonstrable activity with cetuximab plus irinotecan in patients with irinotecan-refractory CRC showed response rates of around 23%, leading to its licensing. Unfortunately, responses did not correlate with the degree of EGFR expression as predicted by preclinical studies. First-line randomized trials with cetuximab combinations with irinotecan (FOLFIRI regimen in the CRYSTAL study) have now established this as a standard of care, and more importantly the clinical–translational work arising has led to the first definitive biomarker of nonresponse to EGFR inhibitors in mCRC. Thus, mutation detection within the important oncogene KRAS leads to resistance to the effects of cetuximab and panitumumab. In liver metastases, the KRAS wild-type (no mutation detectable) subgroup have the highest recorded objective (RECIST) response rates in randomized phase III studies, making triplet combinations with EGFR inhibitors a very attractive, if not the de facto, option in neoadjuvant therapy for potentially operable metastatic disease (i.e., down-sizing of inoperable liver metastases to operable; see also below). Cetuximab’s most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events are hypersensitivity, asthenia, fatigue, malaise, or lethargy. More curiously, an acne-like rash typically associated with HER-1/EGFR inhibition is also observed. Panitumumab is an equivalent humanized version of cetuximab with different scheduling.

- 9.

Two new agents with broader antiangiogenesis activity have recently (2012) gained registration, after positive results from large-scale (phase 3) randomized studies. Regorafenib, an oral multikinase inhibitor has shown a significant survival advantage, after failure of all known chemotherapy drugs (i.e., in the salvage setting), compared to BSC in the CORRECT trial. Similarly, and more impressively, the phase 3 “VELOUR” study of Aflibercept and FOLFIRI, in second line (after failure of an oxaliplatin regimen), also showed a significant survival advantage, even in patients showing resistance to prior bevacizumab exposure. Aflibercept is formed from the fusion protein of key domains from human VEGF receptors 1 and 2 with human IgG Fc1 and blocks all human VEGF-A isoforms, VEGF-B, and placental growth factor (PlGF-2), indeed at such high affinity that it binds VEGF-A and PlGF more tightly as compared to the native receptors. Mechanistically aflibercept is a VEGF-trap, as opposed to a pure VEGF ligand inhibitor such as bevacizumab.

- 10.

Although, “quadruplet’ regimens are being tested, it is unlikely that the increasing and often severe toxicity of these combinations will allow significant dose delivery or intensity, and so benefit will be limited. The randomized trials with these regimens are yet to report, so cannot be recommended at this stage in routine care. Thus, the majority of patients will receive a doublet or triplet as the first-line standard of care.

An understanding of the principles of systemic chemotherapy and rapidly evolving standards of care generated from Level 1 evidence (adequately powered randomized phase III multi-center trials) is very important in the context of a starting framework in the MDT discussion of mCRC, especially if multiple interventions are planned to be integrated, as certain sequences of treatment may be better tolerated as well as being more efficacious.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree