Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) are mucinous cystic tumors of the pancreas, which were first classified into a unified diagnosis by the World Health Organization in 1996. These lesions originate from the cells of the pancreatic ductal system and may grossly or microscopically involve the pancreatic ducts in a diffuse or multifocal fashion. As experience with IPMN increases, it is becoming more evident that this process presents as a spectrum of neoplasia with significant variation regarding the clinical and radiologic presentation, malignant potential, and disease-specific outcome. IPMN encompasses a spectrum of precursor lesions, from adenoma to intraductal carcinoma to invasive cancer, with molecular data supporting the premise that this dysplastic process has the potential to progress from low-grade dysplasia to invasive carcinoma. Controversy over the management of IPMN exists because of the difficulty in obtaining a preoperative histologic diagnosis, the broad spectrum of neoplasia, the lack of understanding as to the frequency and time to malignant progression. This article describes the radiologic and histopathologic classification system of IPMN; the biologic behavior of these lesions, and the diagnostic testing most commonly used, and discusses the current treatment controversies.

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) are mucinous cystic tumors of the pancreas, which were first classified into a unified diagnosis by the World Health Organization in 1996. Other subtypes of cystic pancreatic neoplasm are presented in Table 1 . Before 1996 IPMN were described under a variety of names including mucinous ductal ectasia, papillary carcinoma, and villous adenoma. These lesions originate from the cells of the pancreatic ductal system and may grossly or microscopically involve the pancreatic ducts in a diffuse or multifocal fashion. Some investigators have suggested that IPMN represents a field defect, and in a minority of patients may represent a familial form of pancreatic malignancy.

| Kloppel Classification | |

|---|---|

| Epithelial tumors | Serous cystadenoma |

| Mucinous cystadenoma | |

| Cystadenocarcinoma | |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm | |

| Pseudopapillary and solid tumor | |

| Teratoma | |

| Acinous cystadenocarcinoma | |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | |

| Mucinous cystic adenocarcinoma | |

| Nonepithelial tumors | Cystic islet cell tumor |

| Vascular tumor | |

| Lymphangioma | |

| Hemangiopericytoma | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | |

| Lymphoma | |

| Pseudotumors | Single cyst |

| Polycystic disease | |

| Exclusively pancreatic | |

| With hepatorenal disease | |

| Von Hippel-Lindau disease | |

Because of the increasing use of high-quality cross-sectional imaging, the identification of asymptomatic cystic lesions of the pancreas has increased and a significant percentage of patients with incidentally discovered cysts will have IPMN. As experience with IPMN increases, it is becoming more evident that this process presents as a spectrum of neoplasia with significant variation regarding the clinical and radiologic presentation, malignant potential, and disease-specific outcome. IPMN encompasses a spectrum of precursor lesions, from adenoma to intraductal carcinoma to invasive cancer, with molecular data supporting the premise that this dysplastic process has the potential to progress from low-grade dysplasia to invasive carcinoma. The timing and frequency of this progression is unknown.

At present, the management recommendations for selected patients with IPMN are controversial. Controversy over the management exists because of the difficulty in obtaining a preoperative histologic diagnosis, the broad spectrum of neoplasia, and the lack of understanding as to the frequency and time to malignant progression. Controversy also exists over the extent of operation. In patients without overt evidence of invasive disease, some clinicians have advocated total pancreatectomy as an approach to prevent the development of cancer in a high-risk gland. Others have recommended removal of less than the whole gland in an effort to avoid the long-term morbidity of total pancreatectomy.

This article describes the radiologic and histopathologic classification system of IPMN, the biologic behavior of these lesions, and the diagnostic testing most commonly used, and discusses the current treatment controversies.

Classification of IPMN

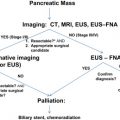

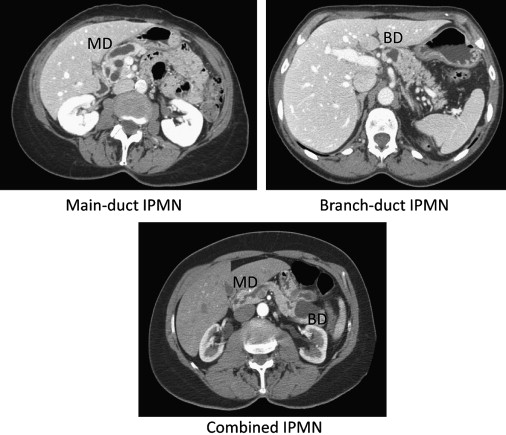

Radiologic

IPMN may present radiographically as diffuse dilation of the main pancreatic duct (main-duct IPMN, MD-IPMN), as single or multiple cystic structures in the pancreas without dilation of the main duct (branch-duct IPMN, BD-IPMN), or a combination of both (combined-type IPMN). Ductal dilation of either the main duct or branch ducts is presumed secondary to the production of mucin within the ductal system and the resultant obstruction of the ducts from this viscous material. The typical radiographic appearance of MD-IPMN, BD-IPMN, and combined-type IPMN is presented in Fig. 1 .

The clinical significance of these radiographic features is that the risk of malignancy is much higher when there is radiographic involvement of the main duct (MD-IPMN, combined-type) than when the main duct is not involved. In a report from Johns Hopkins in 2005, of 136 patients who underwent resection for IPMN the risk of invasive disease was 50% for MD-IPMN, 40% for combined-IPMN, and 30% for BD-IPMN. The percentage of lesions with malignancy varies between institutional reports; however, it is apparent that when there is dilation of the main pancreatic duct, the risk of high-grade dysplasia or invasive disease is 35% to 40%.

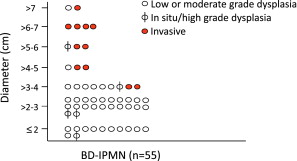

Other radiographic characteristics of malignancy in IPMN have been reported. These features include biliary dilation, the presence of a mass component, and the size of the cyst. In a previous report from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), at the time of resection no patient with a BD-IPMN smaller than 3 cm without concerning radiographic features (no main duct dilation, no solid component) had invasive cancer, and no patient with a lesion smaller than 2.5 cm had high-grade dysplasia. The authors continue to find an absence of invasive carcinoma in patients resected with small BD-IPMN (<3 cm) who do not have concerning radiographic features (no main duct dilation, no solid component). Updated results from patients resected at MSKCC for BD-IPMN are presented in Fig. 2 .

Histopathologic

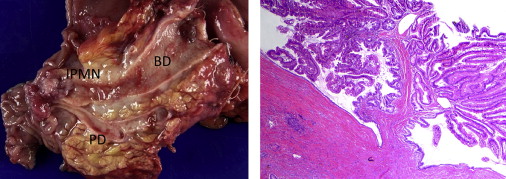

The pathologic classification system of IPMN partially reflects the radiographic system already described. A recent histopathologic consensus conference defined IPMN as a grossly visible, noninvasive, mucin-producing, predominantly papillary or rarely flat epithelial neoplasm arising from the main pancreatic duct or branch ducts, with varying degrees of duct dilation. This report also noted that these lesions are typically greater than 1 cm in diameter, and include a variety of cell types with a spectrum of cytologic and architectural atypia. An example of the gross and microscopic appearance of a typical MD-IPMN is presented in Fig. 3 . The atypia identified in IPMN may range from low-grade dysplasia to invasive malignancy. Current nomenclature (World Health Organization) divides dysplasia within these lesions into the categories of adenoma (low-grade dysplasia), borderline (moderate dysplasia), carcinoma in situ (high-grade dysplasia), and invasive carcinoma.

Differences observed in the microscopic appearance and immunohistochemical profile of the papillae of IPMN have resulted in the further subclassification of IPMN that may provide greater insight into clinical behavior. The histopathologic subtypes identified include pancreaticobiliary, intestinal, gastric, and an uncommon oncocytic subtype. Each subtype can be defined by the appearance under conventional microscopy as well as by immunohistochemical staining. The gastric subtype consists of cells resembling gastric foveolae, which on immunohistochemical staining typically express MUC5AC but not MUC1 or MUC2. This subtype of IPMN is almost uniformly low grade, and some reports suggest that more than 95% of BD-IPMN is of the gastric variety. The intestinal and pancreaticobiliary subtype more frequently demonstrate high-grade dysplasia and are more often observed in the setting of MD-IPMN. MUC2 is frequently expressed in the intestinal subtype and MUC1 in the pancreaticobiliary subtype. The distinction between these 2 subtypes may be clinically relevant, as progression to malignancy in the intestinal subtype is believed to result in colloid carcinoma that has a much better prognosis. The pancreaticobiliary subtype is thought to progress to tubular carcinoma, with a disease-specific outcome similar to conventional pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

The typical radiographic and histologic features of the major subtypes of IPMN are presented in Table 2 . As discussed later in this article, the primary difficulty in managing patients with IPMN is in identifying those with high-grade dysplasia or microinvasive disease. BD-IPMN typically will contain low-grade dysplasia. However, some patients with BD-IPMN will present with or develop high-grade dysplasia or invasive disease. Current research efforts are directed at identifying markers of dysplasia that would allow for a directed approach to resection in patients who present with asymptomatic and radiographically equivocal BD-IPMN.

| Radiographic Classification System | ||||

| Radiographic Subtype | Radiographic Appearance | Dysplasia (Typical) | ||

| Branch duct | Cyst, no main duct dilation | Low | ||

| Main duct | Main duct dilation | Moderate to High | ||

| Combined | Cysts and main duct dilation | Moderate to High | ||

| Histopathologic Classification System | ||||

| Papillae Subtype | Dysplasia (Typical) | MUC1 | MUC2 | MUC5AC |

| Gastric | Low | − | − | + |

| Intestinal | Moderate to High | − | + | + |

| Pancreaticobiliary | Moderate to High | + | − | + |

| Oncocytic | Moderate to High | + | − | + |

Biologic behavior

It is unknown how long it takes for IPMN to progress to malignancy, and whether the majority of lesions will do so. Several studies have reported increased age to be associated with malignancy in IPMN. Because of this reported age difference, a report from Johns Hopkins concluded that the lag time from adenoma to carcinoma in IPMN was approximately 5 years. In a recent study from MSKCC, the authors also found that patients with IPMN adenoma were significantly younger than those with carcinoma (65 vs 74 years, P = .02). The authors believe that this finding most likely represents the time to progression from benign to malignant disease. However, it is important that these reports are surgical series of patients who have undergone resection and therefore, the timing of progression from first radiographic appearance to malignancy is unknown. The authors recently reported from their institutional cyst registry a group of 24 patients with small, primarily BD-IPMN of the pancreas who had been followed radiographically over a period of 12 to 120 months. These patients had incidentally discovered lesions and all patients had cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels greater than 250 ng/mL (BD-IPMN). During the period of follow-up, none of these lesions experienced significant growth or other evidence of malignant progression. Long-term follow-up in this group of patients may provide a more definitive answer to the frequency and rate of progression of IPMN, and comment on the value of CEA as a diagnostic or prognostic marker.

Although the rate and frequency of progression remain unknown it is evident that with the increased utilization of modern imaging, IPMN are being identified earlier in the progression pathway. Current surgical series of resected IPMN report a majority of patients (60%–70%) with noninvasive disease, a majority of tumors (70%) less than 4 cm in size, and up to 40% of patients with incidentally discovered lesions. Comparison of these reports with the initial studies of IPMN supports a distinctly different interpretation of this disease process. In 1978 Compagno and Oertel reported the landmark study of mucinous cystic tumors (IPMN and mucinous cystic neoplasm), which delineated theses lesions from serous cystadenoma. In this study 41 cases were described. The most common method of diagnosis was physical examination (palpable abdominal mass), the average tumor size was 11 cm, and the majority revealed invasive disease (66%). This report included both IPMN and mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), therefore direct comparison should not be made. However, it is clear from these data that current utilization of imaging is identifying patients with IPMN much earlier in the pathway of progression.

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients after resection of invasive IPMN has not been clearly defined. Initial reports with limited follow-up suggested a significantly improved survival for patients with malignant IPMN compared with patients with conventional pancreatic adenocarcinoma. These differences have become smaller as series with longer follow-up are reported; however, there does seem to be a biologic spectrum in the aggressiveness of invasive IPMN. The rate of nodal positivity is typically lower (33%–54%) than for conventional pancreatic adenocarcinoma; however, this may be secondary to the identification of patients with microinvasive disease or very small primary tumors (T1), which is uncommon in conventional adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. In addition, many reports have not separated colloid from tubular carcinoma, and thus the majority of reports suggesting improved survival for patients with invasive IPMN may be secondary to the inclusion of patients with colloid carcinoma.

Colloid carcinoma is known to arise from IPMN and has been associated with the MUC2 positive intestinal subtype (see Histologic classification section). Patients with resected colloid carcinoma have reported 5-year survival rates of between 50% and 60%. Therefore, inclusion of this group in survival reporting of resected IPMN would improve the survival of the entire group. When invasive IPMN has been stratified into colloid and tubular subtypes, the survival of invasive tubular IPMN has seemed similar to what would be expected for conventional pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

After resection for noninvasive IPMN, distant recurrence should not occur; however, these patients have been found to be at risk for recurrence of additional IPMN within the pancreatic remnant. This recurrence is presumably secondary to the concept of a field defect that has been observed in some patients with IPMN. A study from the Mayo clinic reported an 8% gland recurrence rate after partial pancreatectomy for noninvasive IPMN, with a median follow-up of 37 months. These results are similar to those observed at MSKCC and highlight the need to follow patients long-term after resection of noninvasive IPMN for the development of disease within the remnant gland.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree