Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are a heterogeneous group of pancreatic tumors that vary in pathophysiology, malignant potential, clinical course, and outcomes. Their management is heavily predicated on establishing an accurate diagnosis. This can be particularly challenging, but can often be achieved by a thorough history and physical examination combined with high-quality, thin-slice computed tomography, although additional diagnostic tools may be required. Once the diagnosis is established, treatment can range from simple observation to total pancreatectomy. This decision rests on a clear and complete understanding of each disease process in the context of the patient’s age and comorbidities. This article reviews the most common cystic neoplasms of the pancreas, focusing on their diagnosis and management.

Whereas pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma (PDA) is a well-studied (but still poorly understood) disease with a dismal prognosis, cystic neoplasms of the pancreas form a more recently recognized group of pancreatic tumors. They are diverse and variable in their pathologic characteristics, clinical course, and outcomes, although all portend a better overall prognosis than PDA. In recent years, with the improved sensitivity and increasing use of cross-sectional imaging in clinical practice, these lesions are more commonly identified, with many being discovered incidentally. Indeed, large radiological series using computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have reported detection rates of pancreatic cystic lesions between 1.2% and almost 20%, approaching the 24.3% prevalence rate in an autopsy series by Kimura and colleagues. Although most of these lesions are pseudocysts, a significant portion consist of cystic neoplasms, which are estimated to represent 10% to 15% of all primary pancreatic cystic lesions. Given the growing clinical relevance of these tumors, a keen understanding of their natural history and pathophysiology is needed. This article reviews pancreatic cystic neoplasms, with a focus on the challenges encountered in their diagnosis and treatment.

Pancreatic cystic neoplasms

Although pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCNs) are often discussed together, it is important to realize that they are a heterogeneous group of tumors with wide-ranging malignant potential, from benign serous cystadenomas (SCAs) to malignant mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) and invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). They must be differentiated from one another and from other benign processes to ensure appropriate therapy. This distinction, however, is often difficult; misidentification can lead to incorrect management, with dire consequences. For this reason, some have advocated surgical resection of all suspected cystic neoplasms in medically fit patients. Although this aggressive approach minimizes the risk of allowing malignant lesions to progress undisturbed, it subjects patients with benign lesions to unnecessary and morbid operations. An increasing awareness of these tumors and a better understanding of their natural history, coupled with improvements in diagnostic tools, have made it possible to identify more discriminately those lesions that necessitate an operative intervention.

Between 40% and 75% of patients with PCNs experience no symptoms, with the lesion detected incidentally by abdominal imaging performed for the evaluation of another condition. When symptoms are present, they tend to be nonspecific. The differential diagnosis for a PCN is broad ( Box 1 ), but must start with inflammatory pseudocysts, the most common cystic lesion of the pancreas. PCNs are misdiagnosed as pseudocysts in as many as 10% of cases, a significant figure, albeit improved from previously quoted rates. Pseudocysts form as a sequela of the autodigestive tissue necrosis following attacks of acute pancreatitis, and complicate chronic pancreatitis 30% to 40% of the time. A thorough history should detail previously documented episodes of pancreatitis or associated risk factors, including a history of alcohol abuse, biliary pathology, or trauma, and a family history of pancreatopathy. Pseudocysts may develop following pancreatectomy or can result from iatrogenic injuries to the pancreas during surgery on a nearby organ. The clinical picture alone is usually sufficient to make a diagnosis of inflammatory pseudocyst, but is further supported by the following features. Radiographically, a pseudocyst appears as a thick-walled, round, unilocular, well-circumscribed macrocyst that is usually associated with typical pancreatitis findings (eg, gland atrophy or calcification) on CT ( Fig. 1 ). Ultrasound (US) reveals a well-defined echoic structure with distal acoustic enhancement, and possibly internal debris that moves in a dependent fashion with body positioning ( Fig. 2 ). On pathologic examination, pseudocysts contain necrotic/hemorrhagic debris and a turbid fluid rich in amylase and other pancreatic enzymes; their walls are made of inflammatory and fibrous tissue devoid of an epithelial lining, hence the name “pseudocysts.”

Nonneoplastic lesions

Inflammatory pseudocysts

Infectious cysts

Congenital cysts

Duplication cysts

Retention cysts

Lymphoepithelial cysts

Neoplastic lesions

Serous

Serous cystadenoma (SCA)

Serous cystadenocarcinoma (SCAC)

Mucinous

Mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN; adenoma-carcinoma sequence)

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN; adenoma-carcinoma sequence)

Solid pseudopapillary tumor

Cystic variants of solid tumors

Cystic ductal adenocarcinoma

Cystic neuroendocrine tumor

Cystic acinar cell carcinoma

Other nonneoplastic cystic lesions to consider in the differential diagnosis for PCNs include congenital cysts, retention cysts, infectious cysts, and lymphoepithelial cysts. Amongst PCNs, the most common entities (and the focus of this review) are serous cystic neoplasms (SCNs), MCNs, and IPMNs. The remaining members of this group consist of solid pseudopapillary tumors and the cystic variants of normally solid tumors, such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, and acinar cell carcinoma. These tumors are not covered in this review.

SCNs

Introduction

SCNs were first described in 1978 by Compagno and Oertel, who stressed the benign nature of these lesions compared with their mucin-producing counterpart. It is now known that SCNs account for approximately 30% of all PCNs, making them 1 of the most common primary cystic tumors of the pancreas. They are considered benign tumors, although several reports of a malignant version have led the World Health Organization (WHO) to classify 2 categories of SCNs: SCA and serous cystadenocarcinoma (SCAC). SCNs are typically diagnosed in women in their 60s, with the ratio of female/male patients approaching 3 to 4:1. SCNs can grow to large sizes, with a mean size between 5 and 7 cm at the time of diagnosis, and are nearly evenly distributed throughout the pancreas (head vs body and tail). Two major variants exist that differ macroscopically and radiographically, but that are otherwise similar in all other major aspects.

Clinical Presentation

In most SCN cases, the patient is asymptomatic and the lesion is detected incidentally during work-up for an unrelated process. When present, symptoms are usually vague and caused by mass effect, consisting principally of abdominal pain and discomfort and epigastric fullness. Weight loss, nausea, and vomiting occur much less frequently. Despite nearly 50% of SCNs occurring in the head of the pancreas, biliary obstruction causing jaundice is uncommon. Likewise, pancreatic duct obstruction leading to acute pancreatitis is rare. Symptomatology seems to be related to cyst size; Tseng and colleagues found in their series that cysts greater than 4 cm in size were 3 times more likely to be symptomatic than cysts smaller than 4 cm.

A comparative review of malignant and benign SCNs found that patients with SCACs tend to be older by an average of 5 years at the time of diagnosis (66 vs 61 years), and they were more likely to be symptomatic, with 86% of patients experiencing symptoms compared with 66% of patients with SCAs.

Pathophysiology

Unlike MCNs and IPMNs, SCNs are generally regarded as benign lesions. However, this thinking has been challenged by several case reports of SCNs associated with synchronous or metachronous metastatic lesions, most commonly to the liver. Strobel and colleagues calculated the prevalence of SCACs to be 3% of all serous cystic tumors, although they recognize that this figure is likely an overestimation caused by publication bias; the investigators go on to postulate that SCNs, like the mucin-producing cystic neoplasms, may undergo a stepwise benign to malignant progression. This theory is not fully supported by the histologic findings, as less than half of all reported SCACs show any potential signs of malignant growth, such as vascular and perineural invasion or local invasion into the stomach or spleen. Moreover, these criteria are currently not considered diagnostic for malignancy. Instead, the diagnosis of SCAC is established only on documentation of either synchronous or metachronous extrapancreatic metastases. Even in these instances, primary and metastatic lesions are often histologically indistinguishable from benign SCAs, causing some to question whether this is a metastatic neoplasm or a multifocal disease.

Several SCNs have been found to coexist with either another extrapancreatic neoplasm or other distinctly different pancreatic neoplasms, such as ductal adenocarcinomas or islet cell tumors. Patients with von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease are at increased risk of developing SCNs, accounting for 15% to 30% of all such lesions ; referred to as VHL-associated cystic neoplasms, they have a propensity to affect the pancreas diffusely and lack a gender predilection.

A molecular study by Moore and colleagues identified loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at chromosome 10q in nearly half of microcystic SCNs, and LOH at chromosome 3p in 40% of the cases. The latter is the location for the VHL gene, and chromosomal alterations of this particular gene have been reported in a large number of SCAs. Strobel and colleagues implicated the role of Ki-67, a proliferation marker, and p53 in SCACs.

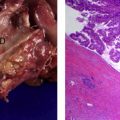

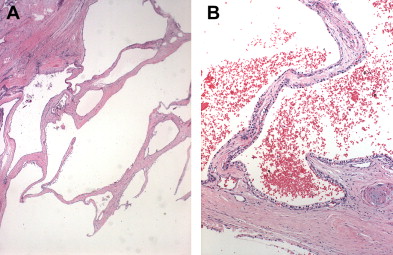

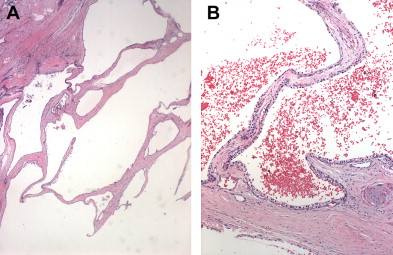

Pathology/Classification

SCNs are characterized by serous fluid-filled cysts lined by a single layer of uniform, cuboidal epithelial cells with round, centrally located nuclei and glycogen-rich clear cytoplasm ( Fig. 3 ). These cells stain positively for periodic acid-Schiff reaction and are believed to originate from centroacinar cells. Two major morphologic variants of SCNs exist that differ in their radiographic and gross appearance, but share the histologic features mentioned earlier. The polycystic microcystic form is more common, accounting for 70% of all SCNs. It often presents as a spongy, bosselated, well-circumscribed collection of multiple small cysts (<2 cm) separated by a central fibrous scar that may contain calcifications arranged in a characteristic stellate pattern. The designation “honeycomb pattern” is sometimes attributed to those tumors with cysts too numerous and small to be discerned as individual cysts on imaging. The second, and much less common variant of SCNs, is the oligocystic form, which has fewer, but larger cysts. For this reason, these are sometimes called macrocystic serous neoplasms. Oligocystic serous neoplasms occur predominantly in the head of the pancreas. As mentioned earlier, the rare SCACs are diagnosed only by the presence of extrapancreatic metastases, but otherwise are histologically similar to the benign SCAs. As a group, SCNs typically do not communicate with the pancreatic ductal system, and have a thin clear wall that separates easily from the surrounding tissue, without inflammatory or fibrous adherence.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of SCNs can usually be achieved radiographically. Most commonly, these lesions are first evaluated with CT, and, in the case of polycystic microcystic tumors, appear as a nonenhancing mass containing multiple small cysts separated by internal septations, resembling a honeycomb ( Fig. 4 ). The identification of a central starburst calcification is pathognomonic of SCN. This finding is the radiographic manifestation of the stellate calcification pattern characteristic of the central fibrous scar of SCNs, but occurs only 30% of the time. Rarely, the cysts are so small that they cannot be distinguished individually, giving the tumor a solid appearance that is of low attenuation on CT. The oligocystic variant, on the other hand, presents a greater diagnostic challenge, because it can resemble either pseudocysts or, more importantly, MCNs. In this situation, Kim and colleagues have identified another CT feature that can assist in the diagnosis: oligocystic SCNs have a distinctive lobulated contour that distinguishes them from MCNs. Location of the mass within the pancreas is helpful also, because oligocystic SCNs are usually found in the head, whereas MCNs tend to grow in the body and tail of the pancreas. It is estimated that, in the appropriate clinical setting, 90% to 95% of SCNs can be accurately diagnosed based on a combination of an indolent course with findings of stromal hypervascularity, a predominance of small cystic areas, and lack of metastases or local invasion on imaging.

For those cases in which a diagnosis remains unclear, other modalities can be used to supplement CT. MRI can show the presence of fluid within the septations of a spongelike mass that appears hyperintense on T2-weighted images; this modality, however, has the disadvantage of being insensitive to calcifications. On endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), SCNs are typically found to have multilobulated borders and an internal honeycomb architecture, although they lack posterior acoustic shadowing. Furthermore, EUS has the additional advantage of allowing sampling of cyst content and cyst wall for cytology and biochemical analysis via fine-needle aspiration (FNA). Often, the cytologic examination of the cyst fluid is nondiagnostic because of the low cellular yield of FNA ; however, Huang and colleagues point out that this scant cellularity can have high predictive value for SCNs if associated EUS morphology is consistent with the diagnosis. When cells are recovered, they stain positively for periodic acid-Schiff reaction for glycogen, negatively for mucin, and lack immunoreactivity for the cytokeratins AE1 and AE3. Cyst fluid analysis should consistently yield a low amylase level, distinguishing SCNs from pseudocysts. Similarly, cyst fluid levels of tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) are typically low, differentiating SCNs from mucinous neoplasms. Serum tumor markers have little to offer in the diagnosis and are not routinely obtained; when increased, serum CEA or CA19-9 levels point to a different diagnosis. Likewise, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) are seldom useful in the work-up of SCNs because these lesions, like MCNs, generally do not communicate with the pancreatic ductal system.

Management

The most crucial aspect in the management of SCNs is definitively establishing the correct diagnosis. Once this diagnosis is achieved, the approach to patients with SCNs should be selective. Most investigators agree that surgery should be offered for patients who experience symptoms, rapid tumor growth, or changes in radiographic appearance, or in whom a definitive diagnosis cannot be obtained. In contrast, some investigators have advocated surgical resection of all cystic neoplasms except in the case of an SCN diagnosed with certainty in older patients or poor surgical candidates. More recently, Strobel and colleagues have cited the risk of malignancy (SCAC) in support of this aggressive approach. Given the generally benign nature of the disease, this strategy seems excessive. Katz and colleagues consider operative intervention to be a reasonable option for tumors whose size is greater than 4 cm, pointing out the report by Tseng and colleagues that these tumors grow more quickly than smaller lesions. In the authors’ practice, tumor size itself is not an indication for surgery, but does usually coincide with the presence of symptoms and rapid tumor growth. These factors, along with the increasingly rare cases in which there remains concern for malignancy, form the only firm criteria for which surgical intervention is warranted in patients with SCAs. If these factors are absent, nonoperative management with observation alone, with at least yearly imaging with high-quality CT, is safe. In separate series, Bassi and Le Borgne and their colleagues followed conservatively managed patients with well-documented SCAs for 69 and 38 months, respectively, and found that none developed significant changes requiring surgery.

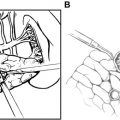

When surgery is indicated, a nonradical, but complete, resection is curative, and long-term survival is excellent, as would be expected for a mostly benign entity. Extended resection and lymphadenectomy are unnecessary and morbid. A lesion in the tail of the pancreas is best addressed by a spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy using a laparoscopic or open approach, whereas a lesion in the head can be removed by pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. Likewise, SCAs in the neck and proximal body of the pancreas can be resected via either a distal-subtotal or a central pancreatectomy. Some investigators have even advocated more limited, localized resection. Talamini and colleagues first described the use of enucleation for benign PCNs in 1998, demonstrating in their series that this operation was associated with shorter operating time and less blood loss, but with a higher incidence of fistula formation, yet equal rates of major complications, than anatomic resections. Kiely and colleagues modified the technique by using intraoperative ultrasound to facilitate identification of the pancreatic duct and permit safe closure of the defect after enucleation, successfully reducing rates of fistula formation to levels achieved for anatomic pancreatectomies. This technique led the investigators to advocate the use of enucleation for small benign cystic neoplasms. The decision to perform this procedure should be based on the surgeon’s skills and comfort level, and should be pursued only in benign cystic lesions, as it is considered by most a suboptimal operation for malignancies.

Although most investigators agree that postoperative surveillance is unnecessary from an oncologic standpoint following complete resection, Galanis and colleagues raise the concern for metachronous metastases in a small subset of patients with SCNs. They advise that patients in whom lesions are found on pathology to exhibit locally aggressive behavior (ie, extension beyond the pancreas into an adjacent organ or local invasion into a blood vessel) despite negative surgical margins may require additional imaging follow-up. However, cases of metachronous metastatic or recurrent disease are so rare that postresection surveillance for SCNs remains unwarranted.

SCNs

Introduction

SCNs were first described in 1978 by Compagno and Oertel, who stressed the benign nature of these lesions compared with their mucin-producing counterpart. It is now known that SCNs account for approximately 30% of all PCNs, making them 1 of the most common primary cystic tumors of the pancreas. They are considered benign tumors, although several reports of a malignant version have led the World Health Organization (WHO) to classify 2 categories of SCNs: SCA and serous cystadenocarcinoma (SCAC). SCNs are typically diagnosed in women in their 60s, with the ratio of female/male patients approaching 3 to 4:1. SCNs can grow to large sizes, with a mean size between 5 and 7 cm at the time of diagnosis, and are nearly evenly distributed throughout the pancreas (head vs body and tail). Two major variants exist that differ macroscopically and radiographically, but that are otherwise similar in all other major aspects.

Clinical Presentation

In most SCN cases, the patient is asymptomatic and the lesion is detected incidentally during work-up for an unrelated process. When present, symptoms are usually vague and caused by mass effect, consisting principally of abdominal pain and discomfort and epigastric fullness. Weight loss, nausea, and vomiting occur much less frequently. Despite nearly 50% of SCNs occurring in the head of the pancreas, biliary obstruction causing jaundice is uncommon. Likewise, pancreatic duct obstruction leading to acute pancreatitis is rare. Symptomatology seems to be related to cyst size; Tseng and colleagues found in their series that cysts greater than 4 cm in size were 3 times more likely to be symptomatic than cysts smaller than 4 cm.

A comparative review of malignant and benign SCNs found that patients with SCACs tend to be older by an average of 5 years at the time of diagnosis (66 vs 61 years), and they were more likely to be symptomatic, with 86% of patients experiencing symptoms compared with 66% of patients with SCAs.

Pathophysiology

Unlike MCNs and IPMNs, SCNs are generally regarded as benign lesions. However, this thinking has been challenged by several case reports of SCNs associated with synchronous or metachronous metastatic lesions, most commonly to the liver. Strobel and colleagues calculated the prevalence of SCACs to be 3% of all serous cystic tumors, although they recognize that this figure is likely an overestimation caused by publication bias; the investigators go on to postulate that SCNs, like the mucin-producing cystic neoplasms, may undergo a stepwise benign to malignant progression. This theory is not fully supported by the histologic findings, as less than half of all reported SCACs show any potential signs of malignant growth, such as vascular and perineural invasion or local invasion into the stomach or spleen. Moreover, these criteria are currently not considered diagnostic for malignancy. Instead, the diagnosis of SCAC is established only on documentation of either synchronous or metachronous extrapancreatic metastases. Even in these instances, primary and metastatic lesions are often histologically indistinguishable from benign SCAs, causing some to question whether this is a metastatic neoplasm or a multifocal disease.

Several SCNs have been found to coexist with either another extrapancreatic neoplasm or other distinctly different pancreatic neoplasms, such as ductal adenocarcinomas or islet cell tumors. Patients with von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease are at increased risk of developing SCNs, accounting for 15% to 30% of all such lesions ; referred to as VHL-associated cystic neoplasms, they have a propensity to affect the pancreas diffusely and lack a gender predilection.

A molecular study by Moore and colleagues identified loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at chromosome 10q in nearly half of microcystic SCNs, and LOH at chromosome 3p in 40% of the cases. The latter is the location for the VHL gene, and chromosomal alterations of this particular gene have been reported in a large number of SCAs. Strobel and colleagues implicated the role of Ki-67, a proliferation marker, and p53 in SCACs.

Pathology/Classification

SCNs are characterized by serous fluid-filled cysts lined by a single layer of uniform, cuboidal epithelial cells with round, centrally located nuclei and glycogen-rich clear cytoplasm ( Fig. 3 ). These cells stain positively for periodic acid-Schiff reaction and are believed to originate from centroacinar cells. Two major morphologic variants of SCNs exist that differ in their radiographic and gross appearance, but share the histologic features mentioned earlier. The polycystic microcystic form is more common, accounting for 70% of all SCNs. It often presents as a spongy, bosselated, well-circumscribed collection of multiple small cysts (<2 cm) separated by a central fibrous scar that may contain calcifications arranged in a characteristic stellate pattern. The designation “honeycomb pattern” is sometimes attributed to those tumors with cysts too numerous and small to be discerned as individual cysts on imaging. The second, and much less common variant of SCNs, is the oligocystic form, which has fewer, but larger cysts. For this reason, these are sometimes called macrocystic serous neoplasms. Oligocystic serous neoplasms occur predominantly in the head of the pancreas. As mentioned earlier, the rare SCACs are diagnosed only by the presence of extrapancreatic metastases, but otherwise are histologically similar to the benign SCAs. As a group, SCNs typically do not communicate with the pancreatic ductal system, and have a thin clear wall that separates easily from the surrounding tissue, without inflammatory or fibrous adherence.

Diagnosis

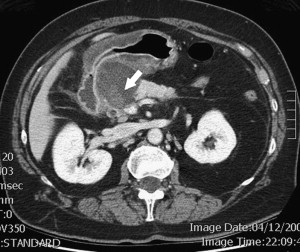

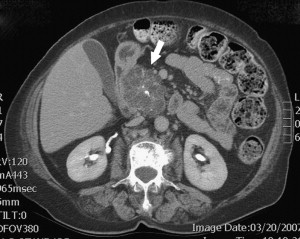

Diagnosis of SCNs can usually be achieved radiographically. Most commonly, these lesions are first evaluated with CT, and, in the case of polycystic microcystic tumors, appear as a nonenhancing mass containing multiple small cysts separated by internal septations, resembling a honeycomb ( Fig. 4 ). The identification of a central starburst calcification is pathognomonic of SCN. This finding is the radiographic manifestation of the stellate calcification pattern characteristic of the central fibrous scar of SCNs, but occurs only 30% of the time. Rarely, the cysts are so small that they cannot be distinguished individually, giving the tumor a solid appearance that is of low attenuation on CT. The oligocystic variant, on the other hand, presents a greater diagnostic challenge, because it can resemble either pseudocysts or, more importantly, MCNs. In this situation, Kim and colleagues have identified another CT feature that can assist in the diagnosis: oligocystic SCNs have a distinctive lobulated contour that distinguishes them from MCNs. Location of the mass within the pancreas is helpful also, because oligocystic SCNs are usually found in the head, whereas MCNs tend to grow in the body and tail of the pancreas. It is estimated that, in the appropriate clinical setting, 90% to 95% of SCNs can be accurately diagnosed based on a combination of an indolent course with findings of stromal hypervascularity, a predominance of small cystic areas, and lack of metastases or local invasion on imaging.

For those cases in which a diagnosis remains unclear, other modalities can be used to supplement CT. MRI can show the presence of fluid within the septations of a spongelike mass that appears hyperintense on T2-weighted images; this modality, however, has the disadvantage of being insensitive to calcifications. On endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), SCNs are typically found to have multilobulated borders and an internal honeycomb architecture, although they lack posterior acoustic shadowing. Furthermore, EUS has the additional advantage of allowing sampling of cyst content and cyst wall for cytology and biochemical analysis via fine-needle aspiration (FNA). Often, the cytologic examination of the cyst fluid is nondiagnostic because of the low cellular yield of FNA ; however, Huang and colleagues point out that this scant cellularity can have high predictive value for SCNs if associated EUS morphology is consistent with the diagnosis. When cells are recovered, they stain positively for periodic acid-Schiff reaction for glycogen, negatively for mucin, and lack immunoreactivity for the cytokeratins AE1 and AE3. Cyst fluid analysis should consistently yield a low amylase level, distinguishing SCNs from pseudocysts. Similarly, cyst fluid levels of tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) are typically low, differentiating SCNs from mucinous neoplasms. Serum tumor markers have little to offer in the diagnosis and are not routinely obtained; when increased, serum CEA or CA19-9 levels point to a different diagnosis. Likewise, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) are seldom useful in the work-up of SCNs because these lesions, like MCNs, generally do not communicate with the pancreatic ductal system.

Management

The most crucial aspect in the management of SCNs is definitively establishing the correct diagnosis. Once this diagnosis is achieved, the approach to patients with SCNs should be selective. Most investigators agree that surgery should be offered for patients who experience symptoms, rapid tumor growth, or changes in radiographic appearance, or in whom a definitive diagnosis cannot be obtained. In contrast, some investigators have advocated surgical resection of all cystic neoplasms except in the case of an SCN diagnosed with certainty in older patients or poor surgical candidates. More recently, Strobel and colleagues have cited the risk of malignancy (SCAC) in support of this aggressive approach. Given the generally benign nature of the disease, this strategy seems excessive. Katz and colleagues consider operative intervention to be a reasonable option for tumors whose size is greater than 4 cm, pointing out the report by Tseng and colleagues that these tumors grow more quickly than smaller lesions. In the authors’ practice, tumor size itself is not an indication for surgery, but does usually coincide with the presence of symptoms and rapid tumor growth. These factors, along with the increasingly rare cases in which there remains concern for malignancy, form the only firm criteria for which surgical intervention is warranted in patients with SCAs. If these factors are absent, nonoperative management with observation alone, with at least yearly imaging with high-quality CT, is safe. In separate series, Bassi and Le Borgne and their colleagues followed conservatively managed patients with well-documented SCAs for 69 and 38 months, respectively, and found that none developed significant changes requiring surgery.

When surgery is indicated, a nonradical, but complete, resection is curative, and long-term survival is excellent, as would be expected for a mostly benign entity. Extended resection and lymphadenectomy are unnecessary and morbid. A lesion in the tail of the pancreas is best addressed by a spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy using a laparoscopic or open approach, whereas a lesion in the head can be removed by pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. Likewise, SCAs in the neck and proximal body of the pancreas can be resected via either a distal-subtotal or a central pancreatectomy. Some investigators have even advocated more limited, localized resection. Talamini and colleagues first described the use of enucleation for benign PCNs in 1998, demonstrating in their series that this operation was associated with shorter operating time and less blood loss, but with a higher incidence of fistula formation, yet equal rates of major complications, than anatomic resections. Kiely and colleagues modified the technique by using intraoperative ultrasound to facilitate identification of the pancreatic duct and permit safe closure of the defect after enucleation, successfully reducing rates of fistula formation to levels achieved for anatomic pancreatectomies. This technique led the investigators to advocate the use of enucleation for small benign cystic neoplasms. The decision to perform this procedure should be based on the surgeon’s skills and comfort level, and should be pursued only in benign cystic lesions, as it is considered by most a suboptimal operation for malignancies.

Although most investigators agree that postoperative surveillance is unnecessary from an oncologic standpoint following complete resection, Galanis and colleagues raise the concern for metachronous metastases in a small subset of patients with SCNs. They advise that patients in whom lesions are found on pathology to exhibit locally aggressive behavior (ie, extension beyond the pancreas into an adjacent organ or local invasion into a blood vessel) despite negative surgical margins may require additional imaging follow-up. However, cases of metachronous metastatic or recurrent disease are so rare that postresection surveillance for SCNs remains unwarranted.

MCNs

Introduction

In 1978, Compagno and Oertel, who had produced a detailed histopathologic report on SCNs that same year, were the first to describe clearly a set of mucin-producing neoplasms in the pancreas that harbored either overt or latent malignancy. It is now known that these tumors are composed of 2 distinct entities: MCNs and IPMNs. Although they share certain characteristics, such as mucin production and a definite malignant potential, these lesions differ in numerous ways, including age and gender distribution, location in the pancreas, and symptomatology. MCNs are generally recognized as (pre)malignant lesions, and when diagnosed, generally warrant surgical resection. They account for 10% to 45% of all PCNs, and are localized in the pancreatic body and tail in 90% of cases.

MCNs are found almost exclusively in women, with few cases reported in men throughout the literature. Affected patients vary widely in age, but in general are younger than patients with SCNs or IPMNs, with the median age at the time of diagnosis of 50 years. Patients with malignant MCNs (mucinous cystadenocarcinoma [MCAC]) are older than their benign MCN-bearing counterpart, by an average of 15 years, reflecting the process of malignant transformation recognized for this disease. Gender distribution and anatomic location seem to differ between benign and malignant lesions also. The large disparity in gender distribution is less pronounced for malignant MCNs, while a review of the literature by Le Borgne and colleagues found that 46% of 156 MCACs were located in the head of the pancreas.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms are more common in MCNs than in SCNs, being present 60% of the time. They are usually nonspecific and caused by compression rather than invasion of adjacent tissue. Most commonly, abdominal discomfort and pain, nausea, and dyspepsia are reported. A previous history of pancreatitis is reported in 10% to 20% of patients ; in these instances, the clinician may confuse the neoplasm for a pseudocyst. Obstructive jaundice is rare because MCNs are predominantly found in the pancreatic body and tail, but does complicate 25% to 54% of those MCNs located in the pancreatic head. Rarely, a firm, round abdominal mass can be palpated in the left upper quadrant that is often tender and moves with respiration. Generally, however, the physical examination is unremarkable.

The presence of symptoms is highly suggestive of malignancy. Nearly all patients with malignant MCN are symptomatic ; in particular, the presence of diabetes mellitus was noted to be strongly associated with malignancy. Other symptoms that may indicate malignancy include obstructive jaundice, anorexia, weight loss, and signs of portal hypertension. Absence of symptoms, however, does not exclude a diagnosis of malignant MCN. A report by Fernandez-del Castillo and colleagues showed that half of asymptomatic, incidentally discovered MCNs harbored either borderline or frank malignancy.

Pathophysiology

Previously collectively classified in the category of mucin-producing cystic neoplasms, MCNs and IPMNs are now known to differ in multiple ways, clinically and pathologically. The major histologic difference between the 2 entities is the presence of ovarian-type stroma in MCNs. This feature has now been established as a key defining characteristic without which a diagnosis of MCN cannot be rendered, according to WHO and the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. This subepithelial stroma shares the same histologic and immunohistochemical profile as that of ovaries, and may provide a clue about the origin of these tumors. The “genital ridge theory” proposes that MCNs arise from cellular stromal elements of the genital ridge that may be associated with the pancreas and could explain the female predominance among MCN patients.

MCNs may undergo a slow process of malignant degeneration in a period of years, from adenoma to borderline malignancy to frank adenocarcinoma, as suggested by the common concurrence of atypia, dyplasia, carcinoma in situ, and invasive carcinoma within the same tumor. Furthermore, the significant age difference between patients with benign and malignant MCNs is consistent with this concept of malignant transformation. Biomolecular studies have shown that the K-ras gene undergoes early mutations in MCNs and does so more frequently with malignancy, leading some investigators to argue that presence of K-ras mutations in the cyst fluid can be used as a marker for malignancy. Likewise, nuclear p53 immunoreactivity indicates malignant changes. DPC4 gene expression is lost in invasive MCNs.

Pathology/Classification

Macroscopically, MCNs are solitary round tumors that have a smooth surface and a fibrous pseudocapsule. They are composed of a few (sometimes only 1) thick-walled macrocysts that are most often multilocular, with internal septations and sometimes an eccentric solid component. Less commonly, the cysts are unilocular, with a smooth glistening internal surface. MCN cysts contain a thick viscous fluid, and in many instances, necrotic, hemorrhagic, or mucinous debris also. They generally do not communicate with the pancreatic ductal system. So few cases of communicating MCNs are reported in the literature that some investigators have questioned whether they might have been IPMNs instead. As a general guideline, presence of a communication favors the diagnosis of IPMN, but does not exclude a diagnosis of MCN.

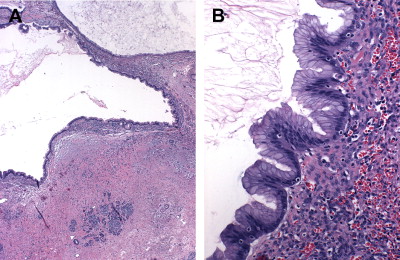

Microscopically, MCNs are defined by the presence of a distinctive subepithelial ovarian-type stroma that distinguishes them from IPMNs. This stroma is histologically and immunohistochemically similar to that of ovaries, including the expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors and human chorionic gonadotropin. It forms a layer of densely packed cells with oval nuclei and spindled cytoplasm arranged in long fascicles that are admixed with luteal-type cells. Overlying this stroma are mucin-secreting, columnar epithelial cells ( Fig. 5 ) exhibiting a wide range of dysplasia, the degree of which combines with presence of tissue invasion to classify MCNs as adenomas, borderline tumors, and adenocarcinomas. Because MCNs can contain focal areas of malignancy interspersed with otherwise benign epithelium within a single tumor, they are classified by the most aggressive histologic finding. It is estimated that the prevalence of invasive carcinoma in MCNs varies between 6% and 36%.

In addition to the common coexistence of benign and malignant areas within the same tumors, MCNs also have a propensity to have a discontinuous epithelial lining, with areas of denuded cyst wall devoid of cells. This occurs in 70% of cases and presents a significant source of sampling errors. For these reasons, a complete histologic examination of the entire specimen on resection is necessary to establish an accurate diagnosis. Several pathologic features can be helpful in distinguishing malignant from benign lesions. Multilocularity, location in the head of the pancreas, and presence of papillary projections and sarcomatous nodules within the stroma indicate, but do not diagnose, MCACs. Likewise, presence of an eccentric solid component, a peripheral calcification pattern, and tumor size greater than 3 cm are concerning for malignancy, although tumors less than 3 cm still carry a near 20% malignancy rate.

Diagnosis

CT is considered an excellent first test in the work-up of a cystic lesion of the pancreas, as it allows characterization of the cyst(s) and the pancreas. In MCNs, the mass will appear as a thick-walled, usually septated macrocyst with smooth sharp boundaries ( Fig. 6 ), surrounded by noninflamed pancreatic tissue that can assist in differentiating it from a pancreatic pseudocyst. Although MCNs do not generally communicate with the pancreatic duct, they can obstruct the ductal system by direct compression of the adjacent pancreatic parenchyma, leading to pancreatic duct dilation, a finding more often associated with IPMNs. However, detection of a communication between the dilated pancreatic ductal system and the lesion should favor a diagnosis of IPMN. CT may also reveal the presence of papillary excrescences or mural nodules, an eccentric solid component, and, in up to 20% of cases, calcifications distributed in an eggshell pattern within the peripheral cyst walls. All of these radiographic findings, along with evidence of pericystic reaction, invasion of surrounding vascular structures, extrahepatic biliary obstruction, metastatic cystic liver lesions, and ascites, are highly suggestive of invasive disease. However, definite preoperative differentiation between benign and malignant MCNs is impossible in most cases.