The Heritage of the Thyroid: A Brief History

Clark T. Sawin

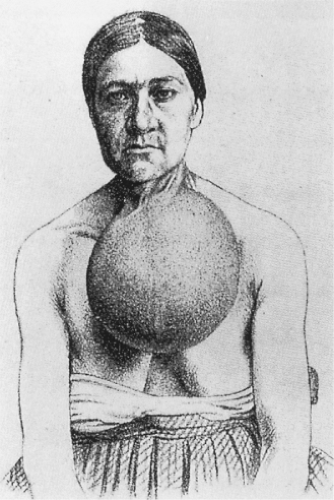

The occurrence of goiter was no surprise to Europeans two millennia ago, especially to those living in the Alps (1). They did not know, however, that goiter was related to the thyroid gland, or that the thyroid gland existed (2). The ancient Greeks called the goitrous swelling in the neck a bronchocele (“tracheal outpouch”); the name was still used in the 19th century, despite the fact that the thyroid gland had been discovered and named 200 years earlier (Fig. 1.1).

The thyroid gland had not been identified as a discrete entity until the Renaissance and the expansion of inquiry into the human body. Leonardo da Vinci probably found it by about 1500, and Vesalius definitely knew about it in 1543 (although he used the term laryngeal glands for the entire gland that we now know as the thyroid gland). By the early 1600s, anatomists definitely identified the thyroid gland in humans and realized that its enlargement caused swelling in the neck, as documented by Fabricius in 1619. The modem name arose in 1656, when Thomas Wharton called it the thyroid gland, after the Greek for “shield-shaped,” not by virtue of its own shape, but because of the shape of the nearby thyroid cartilage (3).

Alpine travelers’ observations of cretinism, a thyroid-linked disorder, can be traced to the 13th century, but clinically relevant descriptions appeared only in the 16th century, when Paracelsus (c. 1527) and Platter (in 1562) made the connection between goiter and cretinism (4).

This was the extent of our knowledge of thyroid physiology and disease until the 19th century. Until then, medical theories behind disease causation were humorally based. An imbalance of the four humors (blood, phlegm, bile, and black bile) caused illness. Some thought that goiter was caused by an excess of phlegm. Treatment was empiric, however, and not based on the theoretical cause. Numerous remedies for goiter were proposed; some were complex mixtures of seaweed and marine sponge. These aquatic substances were well known in medieval Europe and had been used to treat goiter a thousand years earlier in China (some historians believe that the Europeans may have learned of these substances from the Chinese indirectly via traders).

Courtois discovered iodine in the residue of burnt seaweed in about 1812 as an indirect consequence of the British blockade of French ports during the Napoleonic wars. Subsequently, Coindet, an Edinburgh-trained physician working among goitrous people in Geneva, Switzerland, considered iodine to be the active ingredient of the empiric therapies for goiter. In 1820, he gave iodine, mostly as the potassium salt, to patients with goiter, after which their goiters shrank remarkably (5). To his chagrin, he also saw major toxic effects in some patients (not his own) who took too much of the astonishing remedy, which consequently fell into disfavor. Still, iodine continued to be given for other disorders (6) such as scrofula, syphilis, and tuberculosis. Coindet had in fact discovered iodine-induced thyrotoxicosis, the cause of the major toxic effects he had seen; this was the earliest description of any form of thyrotoxicosis, although the true nature of the disorder was not recognized for several decades. Despite the controversy over the use of iodine in Geneva, the therapy represented a shift from an empiric, folk medicine to a rational treatment of a defined illness with a specific substance.

The use of iodine as a drug, even though it was effective at shrinking the goiter in many patients, by no means meant that practitioners knew that they were replacing a deficiency. For most of the 19th century, few accepted the idea that disease could be due to the lack of something. Although the use of iodine to prevent goiter was proposed in 1831 – on the basis of observations in Colombia, South America (7), and later in 1850 by Chatin, a Parisian pharmacist, botanist, and physician (8) – these suggestions were not in tune with the times, were not accepted by the practitioners of that era, and were put aside. Most believed that goiter must be due to something in the water—a toxin, a bacterium, or a parasite. The issue was not resolved until the early 20th century, when small amounts of iodine were found to prevent goiter in schoolgirls in Akron, Ohio (9).

Even then, there was no evidence that these girls were iodine deficient to begin with; the existence of iodine deficiency in certain areas of the United States was not proven for another decade or so.

What has happened since the 1920s is curiously reminiscent of the 19th century: Iodine replacement never became widespread and was eventually abandoned because it was seen as toxic or irrational. This attitude resulted in continued goiter and the associated, but less common, cretinism. After the Akron experiment, the notion of deficiency was slowly becoming accepted, but iodine replacement would still not become widespread for decades. The lesson that iodine is a useful prophylaxis against, and therapy for, goiter and cretinism has still not been put into practice universally. Today, an international consortium (the International Council for the Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders) attempts to ensure that all people receive sufficient amounts of iodine.

The thyroid dysfunctions we know as hypothyroidism and thyrotoxicosis were not thought to be thyroid diseases when described in the 19th century. There was instead a slow accumulation of clinical and physiologic evidence that gradually defined these conditions as we know them today.

Coindet was not the only one to describe thyrotoxicosis without realizing it. Parry, who saw spontaneous thyrotoxicosis

before Coindet, but whose observations went unpublished until after his death (10) (and then in an obscure book published by one of his sons, rather than in a journal), saw a few patients with rapid heartbeat, goiter, and sometimes exophthalmos (exophthalmos was not described by Coindet). Parry thought that this constellation of signs represented some form of heart disease. A few years later, Graves, in his Meath Hospital lectures, described three women who seemed alike (they had goiter and palpitations). His published lectures (11) included a fourth patient who also had exophthalmos. This extra patient had been mentioned to him by his student, friend, and colleague, Stokes. Both Graves and Stokes believed that the illness was cardiac. Graves’ description was not widely known on the European continent, so when Basedow reported somewhat similar patients in 1840 (12), he was thought to be the first to describe the illness. As a result, many Europeans still use the term Basedow’s disease, rather than Graves’ disease, for what in fact should probably be called “Parry’s disease.” Even after Basedow’s report, however, the goiter itself was not considered of much importance. The belief that the syndrome was of cardiac origin faded after about 1860, in part because of Charcot’s emphasis on the nervousness of most patients (13); a neurologic hypothesis was then dominant for the rest of the 19th century. The disorder was still not thought to be a thyroid disease.

before Coindet, but whose observations went unpublished until after his death (10) (and then in an obscure book published by one of his sons, rather than in a journal), saw a few patients with rapid heartbeat, goiter, and sometimes exophthalmos (exophthalmos was not described by Coindet). Parry thought that this constellation of signs represented some form of heart disease. A few years later, Graves, in his Meath Hospital lectures, described three women who seemed alike (they had goiter and palpitations). His published lectures (11) included a fourth patient who also had exophthalmos. This extra patient had been mentioned to him by his student, friend, and colleague, Stokes. Both Graves and Stokes believed that the illness was cardiac. Graves’ description was not widely known on the European continent, so when Basedow reported somewhat similar patients in 1840 (12), he was thought to be the first to describe the illness. As a result, many Europeans still use the term Basedow’s disease, rather than Graves’ disease, for what in fact should probably be called “Parry’s disease.” Even after Basedow’s report, however, the goiter itself was not considered of much importance. The belief that the syndrome was of cardiac origin faded after about 1860, in part because of Charcot’s emphasis on the nervousness of most patients (13); a neurologic hypothesis was then dominant for the rest of the 19th century. The disorder was still not thought to be a thyroid disease.

By the 1880s, surgeons were able to remove the goiters, at least partially, in these nervous, overactive patients without killing many of them, a clear change from 20 years before, when this surgery did in fact kill the majority of patients who were operated upon. Interestingly, the nervousness often disappeared in the survivors. This fact, plus the observation in the 1890s that too much thyroid extract led to similar nervousness and weight loss, brought a shift in thinking toward the thyroid origin of the syndrome. Only in reference to the 1890s and early 1900s can we really speak of thyrotoxicosis, because only then did the concept of an excessive amount of thyroid hormone come into existence as the cause of the syndrome. The concept was applied to both the spontaneous disease and the disease induced by administration of desiccated thyroid. Note that the term thyrotoxicosis is based on another idea of the 1890s, namely, that the thyroid gland in this syndrome either secretes or fails to inactivate a toxin (i.e., a deleterious substance not found in a normal person). The word is still in common use, but it does not reflect the actual pathophysiology, one cause of which is hyperthyroidism, an excess synthesis and secretion of thyroid hormone. The success of partial thyroidectomy over 100 years ago helped focus attention on the thyroid gland, eventually leading to the now more commonly used treatments, radioiodine (14,15) and antithyroid drugs (16).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree