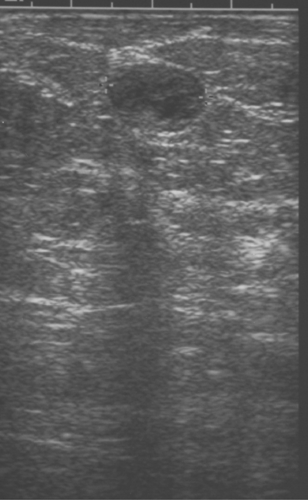

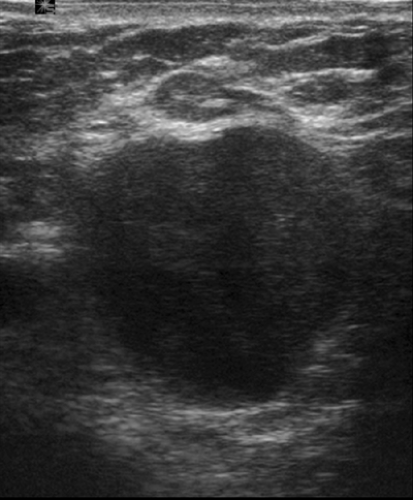

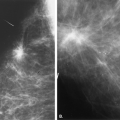

-F3-10″ class=”LK” href=”#F3-10″ onclick=”if (window.scroll_to_id) { scroll_to_id(event,’F3-10′); return false; }” xpath=”/CT{06b9ee1beed59419afb1d25cea40f75410eda93bd71367e2ba4fe76310b9f7e0a87d2d7dabb0784ee9795c995d118448}/ID(F3-10)” title=”10.3″ onmouseover=”window.status=this.title; return true;” onmouseout=”window.status=”; return true;”>10.3). On ultrasound, normal nodes are well-defined, oval, hypoechoic masses with a central echogenic area representing the fatty hilum (Fig. 10.4). Malignant nodes may have eccentric cortical widening (4), an irregular border, and be enlarged, particularly in anteroposterior diameter (Fig. 10.5).

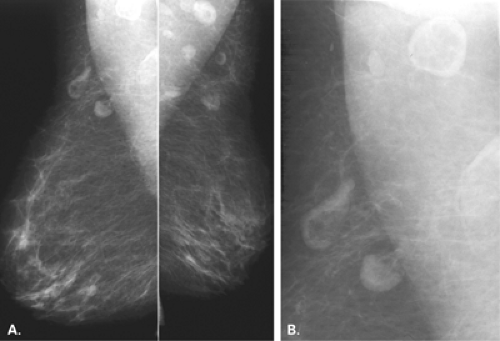

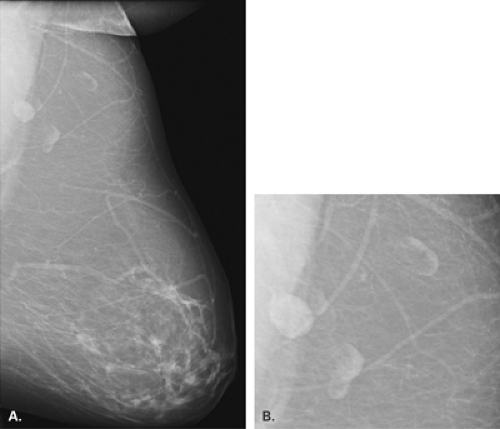

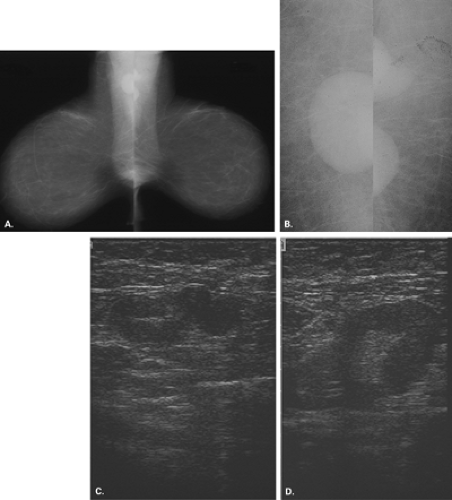

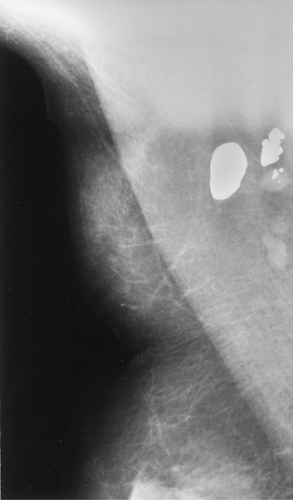

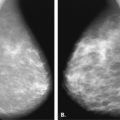

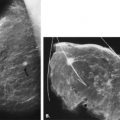

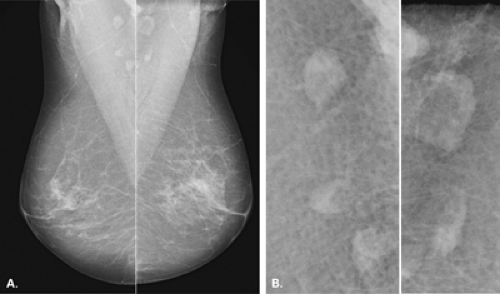

Normal axillary nodes are very-well-defined, medium- to low-density nodules that are less than 1.5 cm in diameter (3) unless fatty replaced. Lymph nodes are round, ovoid, elliptical, or bean shaped. A lucent notch or center is often seen, representing fat in the hilum. This finding helps to confirm the diagnosis of a lymph node (Figs. 10.1,10.2,<A onclick="if (window.scroll_to_id) { scroll_to_id(event,'R5-10'); return false; }" onmouseover="window.status=this.title; return true;" onmouseout="windoroll_to_id(event,'F4-10'); return false; }" title=5 class=LK href="#R5-10" name="tocentrically, producing densities of nodal tissue described as ring, sickle, or crescent in shape. As the fatty infiltration increases, the rim of the lymphoid tissue narrows, eventually leaving a distended capsule surrounding a fatty center (Fig. 10.4). Malignant nodes may have eccentric cortical widening (4), an irregular border, and be enlarged, particularly in anteroposterior diameter (Fig. 10.5).

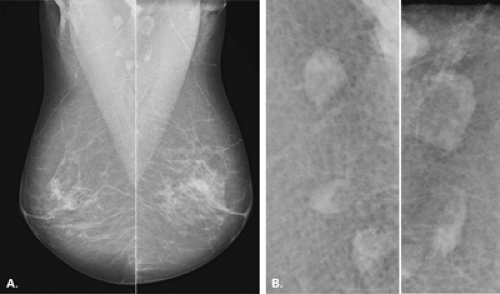

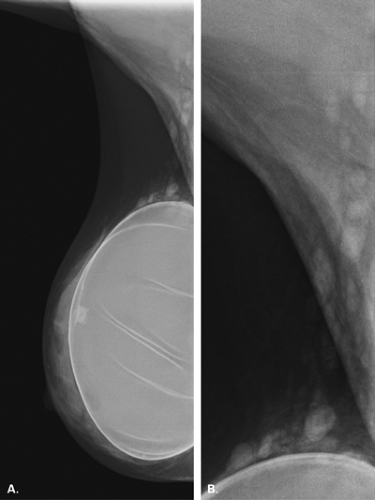

Lipomatosis or fatty infiltration occurs in axillary nodes and is commonly seen in older patients. The fat distends the capsule and enlarges the node, and the surrounding lymphoid tissue atrophies (5). On mammography, these nodes are crescentic and mainly fat containing, often demonstrating only a thin rim of cortex. The node may be 3.5 cm or more in length and be normal when fatty replaced (1,6,7).

In 1965, Leborgne et al. (5) described six patterns of fatty infiltration of nodes. The fatty replacement may occur centrally or ecpearance. They are well defined, reniform, with central fatty hila, all features of benign nodes.

IMPRESSION: Normal axillary nodes.

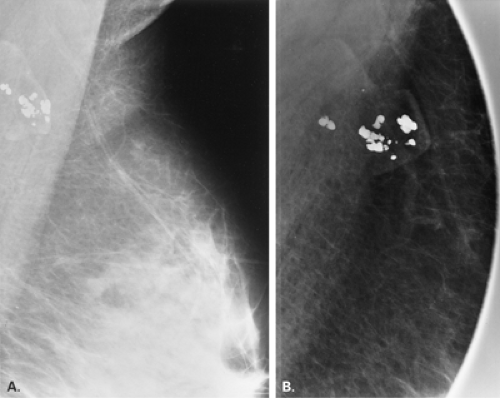

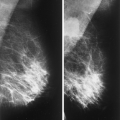

Figure 10.2 HISTORY: A 64-year-old woman for screening. MAMMOGRAPHY: Bilateral MLO views (A) and enlarged images of the axillae (da93bd71367e2ba4fe76310b9f7e0a87d2d7dabb0784ee9795c995d118448}/ID(R3-10)” title=”3″ onmouseover=”window.status=this.title; return true;” onmouseout=”window.status=”; return true;”>3). Adenopathy When approaching adenopathy in the axillae, it is important to try to determine if the process is unilateral or bilateral (Table 10.1). Bilateral adenopathy suggests a systemic etiology that is benign or malignant. Unilateral adenopathy suggests a local or regional abnormality related to the breast or arm, such as breast cancer, mastitis, or an infection in the arm. Although systemic conditions may be associated with nodes that are asymmetrically enlarged, the approach to adenopathy based on unilateral versus bilateral involvement is most helpful in suggesting further management. In a review of 94 patients with axillary abnormalities, Walsh et al. (7) found that in most cases, benign and malignant nodes could not be differentiated from each other by mammography. In this study, 76 of 94 patients had axillary lymphadenopathy, and the causes were as follows: benign lymphadenopathy in 29%, metastatic breast cancer in 26%, chronic lymphocytic leukemia or well-differentiated lymphocytic lymphoma in 17%, and other causes (including collagen vascular disease, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], sarcoidosis, nonbreast metastases) in 28%. Lymph nodes that were not fatty replaced and larger than 33 mm, those that had spiculated margins, and those that contained intranodal microcalcifications were likely malignant.

|