Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Charlotte A. Gaydos

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, 19 million new cases of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) occur annually, costing $10-17 billion per year and primarily affecting adolescents and young adults.1, 2 and 3 This chapter reviews the epidemiology of STDs, the assessment of personal risk factors, and the community factors that contribute to STD morbidity. A number of specific diseases are considered, focusing on the most common organisms, including Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Treponema pallidum (syphilis), Haemophilus ducreyi (chancroid), Trichomonas vaginalis, bacterial vaginosis, and chronic viral infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV) and human papillomavirus (HPV) (Table 24-1).

Understanding the epidemiology of STDs is a critical step in developing rational diagnostic, treatment, and control strategies. In recent years, molecular assays such as nucleic acid amplification assays have revolutionized diagnostic testing modalities.4 At the same time, treatment has become more complex, especially in bacterial infections, because of the emergence of antimicrobial resistance.5 STDs have been conclusively linked to increased risk of HIV transmission and acquisition.6, 7, 8 and 9 Traditional disease control program approaches have included clinic-based screening and partner notification. These measures have been augmented by community-based STD control, including use of computerized disease surveillance systems, geographic mapping, and use of noninvasive new diagnostic specimens and molecular assays, as well as population-based screening in the nonclinical setting. Additionally, issues of health inequity and health disparities make STDs a prime target for management and control. STDs present numerous barriers to routine clinical care and diagnosis, because of the associated stigma, costs, and confidentiality issues.10

Table 24-1 Sexually Transmitted Diseases | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TRANSMISSION MODES: THE DEFINITION OF A SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASE

Sexually transmitted diseases are transmitted through sexual intercourse, which is defined as sexual contact including vaginal intercourse, oral intercourse (i.e., fellatio or cunnilingus), or rectal intercourse. These diseases can be transmitted between either heterosexual or homosexual partners. Different types of sexual activity may result in increased risks. Receptive rectal intercourse and vaginal intercourse carry the highest risks of STD transmission.

CHLAMYDIA

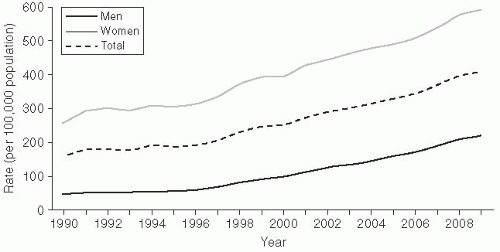

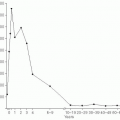

Chlamydia trachomatis infection is the most common bacterial STD in the United States, with approximately 2-3 million cases estimated to occur annually.11 In 2010, there were 1,307,893 cases of chlamydia reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Figure 24-1).3

Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular bacteria, which cause a wide variety of diseases in humans and animals.12, 13 The infections, causes by serovars D-K, are associated with many clinical syndromes, ranging from cervicitis, salpingitis, acute urethral syndrome, endometritis, ectopic pregnancy, infertility, and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in the female; to conjunctivitis and pneumonia in infants; to urethritis, proctitis, and epididymitis in the male.14 Serovars A-C are associated with trachoma, a cause of infectious blindness in the developing world.13

Gender Differences

Men

In men, chlamydia urethritis accounts for approximately 40% of all cases of nongonococcal urethritis in the United States.14 Urethritis in men typically presents as a mucoid discharge, associated often with dysuria. Asymptomatic infection occurs in more than 30% of cases. The time from infection to development of symptoms is usually in the range of 7-14 days.

Rectal chlamydia infection occurs predominantly in homosexual men who have had receptive rectal intercourse.15 As with other infections in gay men, rectal chlamydia has been increasing. Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is a chlamydia syndrome causing inflammatory and ulcerative disease and is caused by the L1, L2, and L3 serovars. From 2003 to 2005, LGV outbreaks causing severe rectal inflammation, mostly in men having sex with men (MSM) with HIV, were reported from the Netherlands and a number of U.S. cities.16

Women

Women bear the burden of most of the morbidity due to chlamydia infections because of the seriousness of the sequelae of infections, especially pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). In women, cervical infection is the most commonly reported syndrome.17 More than half of women with cervical infection are asymptomatic. When symptoms occur, they may manifest as vaginal discharge or poorly differentiated abdominal or lower abdominal pain. At clinical examination, there are often no clinical signs present. When they are present, however, signs include mucopurulent cervical discharge, cervical friability, and cervical edema.18

Left untreated, approximately 30% of women with chlamydial infection will develop pelvic inflammatory disease.18 The PID seen in conjunction with chlamydia is associated with lower rates of clinical symptoms than the PID seen with gonorrhea. However, this subacute PID is associated with higher rates of subsequent infertility because chlamydia induces an inflammatory reaction characterized by fibrosis.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of chlamydia is interesting because the reporting scheme includes a number of artifacts. Reported chlamydia infections are more common in women (610.6/100,000) than in men

(233.7/100,000), and rates have increased substantially since 1984 (Figure 24-1).3 Both of these trends may be somewhat artificial, however. The rate differential between women and men is mainly due to different ascertainment and reporting practices. Women are typically diagnosed with an etiologic diagnosis of chlamydia on the basis of a chlamydia screening test performed at physical examination. Clinical practice guidelines strongly recommend routine chlamydia screening for sexually active women younger than the age of 25.5, 19 This practice has also been incorporated into quality assurance guidelines for managed care organizations (HEDIS).20 In contrast, men are often treated for chlamydia infection on the basis of presentation of a syndrome of urethritis or as a contact to a woman with chlamydia, with definitive etiologic diagnoses never being made. As a consequence, these cases may not meet surveillance definitions for chlamydia and may not be reported.

(233.7/100,000), and rates have increased substantially since 1984 (Figure 24-1).3 Both of these trends may be somewhat artificial, however. The rate differential between women and men is mainly due to different ascertainment and reporting practices. Women are typically diagnosed with an etiologic diagnosis of chlamydia on the basis of a chlamydia screening test performed at physical examination. Clinical practice guidelines strongly recommend routine chlamydia screening for sexually active women younger than the age of 25.5, 19 This practice has also been incorporated into quality assurance guidelines for managed care organizations (HEDIS).20 In contrast, men are often treated for chlamydia infection on the basis of presentation of a syndrome of urethritis or as a contact to a woman with chlamydia, with definitive etiologic diagnoses never being made. As a consequence, these cases may not meet surveillance definitions for chlamydia and may not be reported.

The trend of increasing incidence of infection likely results from increased screening activity, because women are routinely screened for this STD (and men are not).3 The ascertainment bias favors increased disease reporting in women. A true estimate of chlamydia prevalence is not known, which presents major problems in evaluating trends.11

The rates of chlamydia are highest in adolescent women and drop off steeply past that age. For example, the reported rate for women between the ages of 15 and 19 is 3,378.2/100,000, but drops off to 530.9/100,000 for women ages 30-34.3 There is a strong hypothesis that this steep decline in incidence may not be related solely to behavior, but rather may also reflect the development of partial immunity to clinical infection through periodic repeated exposures.

Diagnosis

Advances in chlamydia testing technology since the early 1980s have resulted in easy, assessable chlamydia screening being available. Before 1984, chlamydia testing was available only by tissue culture, which was expensive and cumbersome, or by direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) testing, which was labor intensive. The nonculture tests that were developed were not sensitive. Currently, molecular nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) can be performed both on urogenital specimens, such as cervical and urethral swabs, as well as vaginal swabs, and on urine.4, 13, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 and 29 The development of new, noninvasive urine- and vaginal-based, nucleic acid-based technologies has resulted in substantial expansion of screening activities because of the reduced need to perform clinical pelvic exams. Most test formats have combined the gonorrhea and chlamydia assays into a single test platform. Many of the new assays can also be performed robotically.30, 31 and 32

Chlamydia screening programs have been demonstrated to be cost-effective.33, 34 and 35 Screening intervention programs can affect chlamydia prevalence and be instrumental in preventing PID and sequelae such as hospitalization by removing infected individuals from the prevalent pool of the population.36, 37, 38 and 39

GONORRHEA

Gonorrhea is a bacterial exudative infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a fastidious gram-negative bacteria.40 N. gonorrhoeae was first described by Neisser in 1879, and is a gram-negative, nonmotile, non-spore-forming diplococcus, belonging to the family Neisseriaceae. Gonorrhea is one of the oldest diseases known to humans; the term, which is Greek and means “flow of seed,” was first coined by Galen; clinically, gonorrhea was described in the Old Testament of the Bible as well as in ancient Chinese, Greek, Roman, and Egyptian writings.40, 41 The other pathogenic species is N. meningitidis, to which N. gonorrhoeae is genetically closely related. Although N. meningitidis is not usually considered to be an STD, it may infect the mucous membranes of the anogenital area of homosexual men.42

Gender Differences

Men

In men, urethritis is the most common syndrome associated with gonorrhea. Discharge or dysuria usually appears within one week of exposure, although as many as 5-10% of patients never have signs or symptoms. Asymptomatic disease can exist in men for as long as several weeks after infection.40 Nevertheless, during this time the infectious organism is potentially transmissible to sexual partners. Epididymitis and epididymo-orchitis can occur as a complication of untreated gonococcal infections, but can also be caused by chlamydia, coliforms, or Pseudomonas. The incidence of epididymitis is estimated to be in the range of 1-4 cases per 1000 men per year.43

Symptomatic anorectal gonococcal disease occurs in persons with a history of receptive rectal intercourse.44 Approximately 50% of these patients have symptoms of rectal pain, discharge, constipation, and tenesmus. Anorectal disease can also occur in women who have endocervical gonorrhea and who

have not necessarily had receptive rectal intercourse. In these cases, infection is presumed to have occurred via tracking of secretion across the perineum. Indeed, as many as 30% of such women often have coexistent rectal infection, though it is usually asymptomatic.

have not necessarily had receptive rectal intercourse. In these cases, infection is presumed to have occurred via tracking of secretion across the perineum. Indeed, as many as 30% of such women often have coexistent rectal infection, though it is usually asymptomatic.

Because rectal gonorrhea in men implies a history of unprotected rectal intercourse, surveillance of rectal gonorrhea has been useful as a surrogate marker for HIV risk in MSM. Starting in 1997, troubling reports of an increase of gonorrhea in MSM surfaced, with this trend continuing into the present.3 From 1990 to 2010, the proportion of isolates from MSM in selected STD clinics from the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) has increased steadily from 4.6% to 28.9%, with the largest proportion of isolates being noted on the West Coast.3

Women

In women, gonorrhea typically causes cervical disease (cervicitis). Women with untreated gonococcal cervicitis, as well as untreated chlamydia infections, develop upper tract infection and/or pelvic inflammatory disease.47, 48 Other organisms, such as anaerobes, Gardnerella vaginalis, enteric gram-negative rods, and other pathogens, such as Mycoplasma genitalium and bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora, may also be associated with PID.5

Epidemiology

In 2010, 309,341 cases of gonorrhea in the United States were reported to the CDC by local and state health departments, representing a nationwide population-based rate of 110.8/100,000; this rate has been fairly stable since 1997.3 An additional 1-2 cases are thought to occur for every officially reported case. The highest rates are seen in adolescent women (age 15-19 years) and young adult men (20-24 years), representing, in part, sexual behavior patterns.

One of the problems with the CDC-reported data is that they are based on a passive case-based reporting system. Population-based studies have demonstrated that the epidemiology of incident symptomatic disease, as represented by passive reporting, is different from prevalent asymptomatic infection. For example, in a survey conducted in Baltimore in 1997-1998, a population-based sample of individuals aged 18-35 years were interviewed in their households, and urine samples were assayed by NAAT for chlamydia and gonorrhea. Gonorrhea estimates using this population were more than three times greater than the rates reported by health departments.49 Although gonorrhea incidence has decreased by nearly 70% since the peak of the gonorrhea epidemic in the mid-1970s, the infection has become increasingly prevalent in inner-city areas affected by other social problems, especially drug use and pregnancy. In these areas, incidence rates among adolescents often exceed 15% per year.

Disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI), or gonococcal septicemia, occurs in approximately 0.5-3% of untreated gonococcal cases.40 DGI is more commonly seen in women, in particular during pregnancy, and is also more common in persons with complement deficiencies.

Perinatal Disease

Perinatal infection with gonorrhea is relatively rare in the United States, but is often found in the developing world. Perinatal gonococcal disease is transmitted by direct exposure, as an infant passes through the birth canal of an infected cervix.

Gonococcal ophthalmia is a severe public health problem in the developing world and can be effectively prevented with inexpensive prophylaxis. The incidence of gonococcal ophthalmia is estimated to be 42% of infants exposed to an infected cervical canal. These infants develop a purulent conjunctivitis that can then rapidly progress to keratitis and subsequent corneal blindness. Because of the severe sequelae of this infection, public health authorities instituted postnatal prophylaxis with ophthalmic silver nitrate as early as 1910, effectively preventing corneal infection in 95% of exposed infants. Prevention of perinatal infection is the rationale for aggressive screening programs in pregnant women.

The same perinatal ophthalmia can be caused by C. trachomatis. Ophthalmia is also occasionally seen in adults, usually as a result of self-inoculation.

Diagnosis

The gold-standard diagnostic approach for gonorrhea has traditionally been culture; culture involves many operational considerations, such as logistical requirements and environmental requirements. Specimens should be inoculated onto nonselective media (chocolate agar), upon which all Neisseria spp. will grow, or selective media, such as modified Thayer-Martin (MTM). Selective media contain antimicrobial agents that inhibit the growth of commensal bacteria, nonpathogenic Neisseria spp., and fungi. Because pathogenic Neisseria spp. are nutritionally and environmentally fastidious, the ideal

method for transporting organisms for culture is to plate the specimens directly onto the culture medium and immediately incubate the plates in an increased humidity atmosphere of 3-5% CO2, at a temperature of 35-37°C.

method for transporting organisms for culture is to plate the specimens directly onto the culture medium and immediately incubate the plates in an increased humidity atmosphere of 3-5% CO2, at a temperature of 35-37°C.

A direct Gram stain may be performed as soon as the specimen is collected on site, or a smear may be prepared and transported to the laboratory. Urethral smears from males with symptomatic gonorrhea usually contain intracellular gram-negative diplococci in polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs). Extracelllular organisms may be seen as well, but a presumptive diagnosis of gonorrhea requires the presence of intracellular diplococci. The sensitivity of such smears in males ranges from 90% to 95.0%.50 However, endocervical smears from females and rectal specimens require diligent interpretation, owing to colonization of these mucous membranes with other gram-negative coccobacillary organisms. In females, the sensitivity of an endocervical Gram stain is estimated to be 50% to 70.0%.50

Nucleic acid amplification tests, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), standard displacement amplification (SDA), transcription-mediated amplification (TMA), and real-time PCR, are now widely used and are the most common gonorrhea (and chlamydia) tests performed in the United States today.29, 51 NAATs are more sensitive in certain situations and can be used on nongenital samples, such as urine and vaginal swabs. The use of urine as a diagnostic technique has facilitated expansion of gonorrhea screening efforts, especially in populations where clinical service provision is difficult and/or inadequate.

Treatment

Treatment for mucosal gonorrhea infections is based on providing single-dose regimens, preferably oral, that are effective against most or all of the known resistant determinants.5 Current regimens include either a quinolone (see the discussion of resistance in the next subsection) or a third-generation cephalosporin. All patients treated for gonorrhea should also be treated for chlamydia, with either azithromycin 1 gram (single dose) or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 1 week. The chlamydia recommendation is based on the high rate of gonorrhea/chlamydia coinfection, which may be as high as 30-40%.5

N. gonorrhoeae has tremendous capacity to develop antimicrobial resistance. For 30 years after World War II, penicillin was the antimicrobial therapy of choice. In 1976, the first case of plasmid-medicated penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae (PPNG) was reported. PPNG rapidly developed into a major public health problem and made the penicillin class of antibiotics obsolete by the mid-1980s. Chromosomally mediated resistance to penicillin (CMRNG) was described in the early 1980s, high-level plasmid-mediated tetracycline resistance (TRNG) developed in 1986, and quinolone antibiotic resistance (QRNG) appeared in the late 1990s.52

Development of standardized effective gonococcal treatment strategies has required accurate surveillance, which has occurred since the mid-1980s with the implementation of the national gonorrhea surveillance network. This multisite surveillance system has provided standardized mechanisms for determining antimicrobial resistance. As a by-product of that system, the CDC’s Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) recently described increased incidence of anorectal infection in the GISP cohort, suggesting that unprotected anal intercourse was increasing within the homosexual community surveyed by the GISP program. This trend presents a very troubling public health issue, as it indicates a higher risk profile for all STDs, including HIV.

Quinolone Resistance

Quinolone resistance has rapidly emerged as a major public health problem in gonorrhea treatment. Quinolone resistance is mediated by mutations in the gyrase and topoisomerase genes in the gonococcal genome, which render high-level resistance to the quinolone class of drugs. This development has had major implications. For example, in parts of Southeast Asia, more than 50% of gonococcal isolates consist of QRNG.53 From 2002 to 2004, this development rapidly spread to the western United States and Hawaii. More recently, QRNG has been associated with as many as 10-15% of isolates in the United States in homosexual men. For this reason, quinolones are no longer recommended as first-line therapy for gonorrhea.5 Recently, ceftriaxone-resistant gonorrhea has been isolated and cefixime treatment failures have occurred, leading to the disturbing forecast of a future era with untreatable gonorrhea.54, 55 and 56

Population-Based Surveys for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea Diagnostic Testing

The availability of nucleic acid amplification tests has revolutionized gonorrhea and chlamydia diagnostics. NAATs are highly sensitive and are able to detect as few as 10 organisms per specimen. These tests have been applied in a large number of field settings, including emergency departments, job centers, middle and high schools, and military training sites. The largest studies have been done in military

recruits being inducted at large bases in the eastern United States that processed inductees from all 50 states; these investigations found prevalences of 10% in females and approximately 5% in male recruits.39, 57, 58 and 59 In another sample, consisting of more than 12,000 adolescents in the United States, the overall prevalence of chlamydial infection was estimated to be 4.2%.60 Hospital emergency departments have also been sites for urine screening of young adults presenting for reasons other than reproductive health care and have demonstrated high prevalence as well.61, 62 and 63

recruits being inducted at large bases in the eastern United States that processed inductees from all 50 states; these investigations found prevalences of 10% in females and approximately 5% in male recruits.39, 57, 58 and 59 In another sample, consisting of more than 12,000 adolescents in the United States, the overall prevalence of chlamydial infection was estimated to be 4.2%.60 Hospital emergency departments have also been sites for urine screening of young adults presenting for reasons other than reproductive health care and have demonstrated high prevalence as well.61, 62 and 63

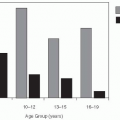

Combining the NAAT technology with population-based surveys provides new insights into the burden of these STDs in the general population. A survey in Baltimore provided estimates representative of adults living in the city between the ages of 18 and 35 years.49 The prevalence of gonococcal infection overall was 3.0% in all adults aged 18 to 35 years; it ranged from 8% in 19- and 20-year-olds to 0.5% in 33- to 35-year-olds.

PELVIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASE

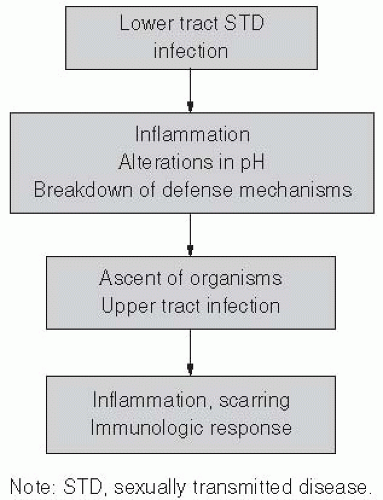

PID is most often considered to be a result of gonorrhea, chlamydia, enteric organisms, and anaerobic organisms, but is a poorly defined syndrome, in part because it affects multiple organs and is not associated with any clearly defined diagnostic criteria (Figure 24-2). Semantically, PID represents infection of the soft tissues of upper genital tract structures and includes endometritis, salpingitis, oophoritis, and pelvic peritonitis. Fatalities from PID are rare, but severe disease may lead to tubo-ovarian abscess and at times the necessity for hysterectomy. Chronic complications are more common. Women with previous history of PID are more likely to have tubal-factor infertility and are at higher risk for ectopic pregnancy.64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 and 71 The overall direct economic impact of PID alone has been estimated to be $4.2 billion.72

The consequences of PID were eloquently shown by Westrom in a large cohort of Swedish women.68, 73, 74 and 75 He diagnosed all cases of PID by laparoscopy (the gold-standard diagnostic procedure) and followed them for over 25 years—from adolescence through the childbearing years. According to these data, 10% of women with one PID episode had tubal infertility, 25% of those who had two episodes had tubal infertility, and more than 60% of women with three episodes had tubal infertility. The relative risk of ectopic pregnancy was greater than 10 compared to women without one episode of PID. Because these complications occur long after the initial infective process, the epidemics of infertility and ectopic pregnancy track the initial epidemic of gonorrhea or chlamydial infection by a substantial latency period.

In the United States, an estimated 500,000 to 1,000,000 cases of PID occur annually.3 Estimates of PID incidences vary and are made more difficult by the lack of prospective studies, as well as the difficulty in clinical diagnosis.48 Ascertainment of disease burden is difficult because PID syndrome is not a reportable disease. The CDC reported 113,000 cases of PID from Initial Visits to Physicians’ Offices and the National Disease and Therapeutic Index Surveillance for 2010, but the actual burden of cases is estimated to be much higher.3 Changes in the U.S. healthcare system in recent decades have emphasized outpatient management of STDs. Therefore, although hospital discharges for PID since 1990 have dropped sharply, these data are considered unreliable because of the confounding caused by changing practice patterns.

PID is associated with adolescence, increased number of sexual partners, a previous episode of PID, use of an intrauterine device, and douching.76, 77, 78 and 79 Clinical criteria that have been traditionally used for diagnosis include two of three major criteria: lower abdominal pain, adenexal tenderness, or fever.78 Some sources have also added the presence of a lower tract infection (gonococcal or chlamydial cervicitis). Careful studies of clinical criteria that have used laparoscopy as the standard for diagnosis of PID found that the sensitivity and specificity of clinical criteria is 60-70% in expert hands.80 As many as one-fourth of PID cases may not demonstrate symptoms, especially disease associated with chlamydia. Given this fact, many practitioners currently treat women with mild

cervical motion tenderness with treatment regimens effective against PID under the assumption that the benefit of preventing pelvic inflammatory disease or curing early pelvic inflammatory disease outweighs the costs in terms of increased cost of treatment and potential side effects.

cervical motion tenderness with treatment regimens effective against PID under the assumption that the benefit of preventing pelvic inflammatory disease or curing early pelvic inflammatory disease outweighs the costs in terms of increased cost of treatment and potential side effects.

Treatment strategies for PID are based on the underlying microbiology, including antimicrobial coverage for N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, streptococci, gram-negative rods, and anaerobes.81 Treatment regimens are complex (and beyond the scope of this chapter), but guidelines are issued every two years by the CDC.5

Despite the strides made in developing effective antimicrobial regimens, treatment efficacy has proved difficult to assess. Most clinical treatment studies use clinical criteria for determination of efficacy, despite the limitations of clinical diagnosis. Therefore, these studies are subject to both type I and type II statistical errors. Furthermore, although the morbidity of PID is a long-term phenomenon, few treatment studies have correlated effective antimicrobial therapy with better long-term outcomes in terms of reduced incidence of infertility and ectopic pregnancy. Treatment of acute PID is considered to be secondary prevention. The consensus regarding primary prevention is that reducing gonococcal and chlamydial infections is the most effective approach.82 Screening interventions for chlamydia have demonstrated reductions in PID prevalence of more than 60%.36

SYPHILIS

Syphilis is a bacterial sexually transmitted disease caused by Treponema pallidum.83 Traditionally, syphilis has been divided into three clinical stages: primary, secondary, and late (including tertiary and late benign syphilis). Latent syphilis is a serological diagnosis for which symptoms are not apparent and which is differentiated into early (infection duration less than 1 year) or late (infection duration greater than 1 year).84

Epidemiology

Transmission of syphilis is relatively inefficient. Studies have demonstrated that the transmission efficiency of this disease between an infected partner and an uninfected partner is only 20%. After the initial exposure, a latency period of three weeks passes prior to the development of the initial symptoms. During this latency period (or, in epidemiologic terms, the “critical period”), a newly infected individual is not infectious to his or her sexual partners. However, this status changes rapidly after development of the initial genital ulcerative lesion (chancre). The chancre is a primary syphilis ulceration that occurs at the site of mucosal inoculation.

Syphilis occurs in settings where there is high turnover of sex partners. Commercial sex workers and other transient individuals with multiple sex partners are at increased risk. In developed countries, moreover, syphilis has been associated with a variety of social and behavioral factors, including bathhouses frequented by homosexual men, prostitution related to drug abuse, and poor access to health care.85 In the developing world, more important issues are prostitution, transience, and poor access to health care.

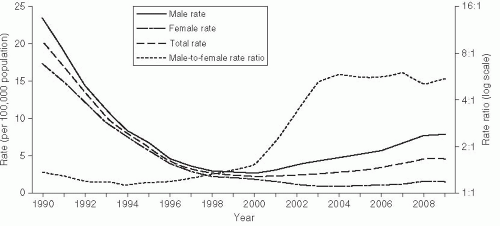

Syphilis rates in the United States reached a plateau in the late 1960s and continued to drop until 1975. At this time, the epidemiology of syphilis reflected the broader, societal social trends in the United States (Figure 24-3). During 1975-1980, rates increased nearly 50%, but nearly all of the increase was due to greater incidence among homosexual men. MSM culture was undergoing the “gay revolution” at this time, with homosexual men demonstrating increased sexual openness and pride in their sexual orientation. During 1980-1985, rates declined by 40% as men dramatically reduced their sexual risk practices in response to the HIV epidemic. Rates again increased nearly 100% between 1985 and 1991 (Figure 24-3).86 This epidemic was due to increased rates among heterosexuals, especially racial and ethnic minorities, and corresponded to increased use of crack cocaine, which was introduced to the United States in 1985. Aggressive control programs, especially a large national syphilis elimination effort in African American communities that included extensive medical ethnography and grassroots efforts, led to a sustained decrease in syphilis rates in this community since 1991.5, 87

More recently, as described earlier, syphilis has again increased in MSM, just as it did in the 1970s. Increased rates of risky sexual behavior in MSM have been correlated with a reduction in concern about HIV due to the development of highly effective antiretroviral therapy and “safe-sex fatigue,” where men are tired of maintaining safe sexual practices.3

Clinical Course

Initial infection with T. pallidum occurs through sexual contact at a mucosal membrane. The incubation period for this infection ranges between 10 and 30 days.84 Typically, 3 weeks after the initial

exposure, a chancre develops at the site of contact. The chancre is a painless lesion with an indurated border and has associated painless lymphadenopathy. Syphilis is a systemic disease, however—even in primary syphilis, systemic dissemination may occur. In some studies, 10% to 15% of patients with early primary syphilis have demonstrated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) abnormalities.88 Left untreated, the chancre spontaneously heals within 2-3 weeks.

exposure, a chancre develops at the site of contact. The chancre is a painless lesion with an indurated border and has associated painless lymphadenopathy. Syphilis is a systemic disease, however—even in primary syphilis, systemic dissemination may occur. In some studies, 10% to 15% of patients with early primary syphilis have demonstrated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) abnormalities.88 Left untreated, the chancre spontaneously heals within 2-3 weeks.

Four to eight weeks later, the secondary syphilis syndrome develops. Secondary syphilis consists of a systemic vasculitis caused by high levels of T. pallidum in the blood and associated immunologic responses. The most characteristic findings are dermatological in nature, including the classic palmar plantar rash, but patterns may include papular, maculopapular, papulosquamous, and psoriasiform lesions. Patchy alopecia may develop, especially on the scalp. On the mucosal surfaces, mucous patches may be noted. Condyloma lata—large, fleshy, wart-like lesions— may develop on the genitalia. Condyloma lata and mucous patches are highly infectious. Left untreated, the secondary syphilis syndrome spontaneously resolves usually within 1-2 months of onset.

Late complications of syphilis, such as neurosyphilis, cardiovascular syphilis, and gummatous syphilis, do not develop until 10-20 years after the resolution of early syphilis. In HIV patients, case reports have suggested that late complications may occur earlier.89

Early latent syphilis is a serologic diagnosis in which a fourfold increase in titer (i.e., two dilutions) occurs within 1 year with previous documentation of the earlier serology. Late latent syphilis is a serologic diagnosis of syphilis occurring more than 1 year after baseline diagnosis. The differentiation between early latent and late latent syphilis has both treatment and public health implications.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of syphilis is complex because the organism cannot be cultured, and serological tests have been largely unchanged for half a century. In primary cases, the organism can be visualized by dark-field microscopic examination, but realistically this procedure is not available in most settings.

Serological diagnosis of syphilis is a two-step procedure.90 Previously, a nontreponemal screening test was performed as the initial step, which would be followed by a more specific treponemal test as the confirmation test. The advent of new enzyme immunoassay treponemal tests recently has resulted in an increase of the use of a treponemal test, using recombinant antigens, as the initial test in many laboratories, however.91 This test is then followed by a non-treponemal test to determine a titer. This practice has resulted in some confusion among clinicians when the initial treponemal test is positive, but the non-treponemal test is negative regarding the serological status of the patient. The CDC and others have recommended algorithms to be followed for interpretation in such cases. Implications for clinical management include the need for analysis of patient risk factors, further confirmatory testing by another treponemal test such as the Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) assay, and determination of whether the patient may have had prior treated syphilis.91, 92, 93 and 94

The most widely used non-treponemal tests are the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests. Results for these tests are reported as titers (i.e., the dilutions required to achieve a negative reaction using standard reagents). Patients with a positive non-treponemal test should have a confirmatory test such as TP-PA assay, the fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorbed (FTA-ABS) test, or microhemagglutination (MHATP) test. As many as 20% of patients with positive non-treponemal tests have negative confirmatory tests; these are termed benign false positives (BFP). Most frequently, these outcomes are seen in patients with past series of intravenous drug abuse, pregnancy, systemic disorders such as lupus, and other infectious processes such as Lyme disease. Patients with BFP results and with titers greater than 1:16 are extremely unusual.

In primary syphilis, the sensitivity of serologic testing is 85%. In this setting, false-negative cases may occur because seroconversion may occasionally take longer to develop than the genital ulcer. In secondary syphilis, sensitivity of serological diagnosis is close to 100%. Titers in secondary syphilis may be extremely high. In latent syphilis, the serological tests are positive, but patients do not have corresponding clinical symptoms.

Syphilis in HIV-Infected Patients

All stages of syphilis are seen more commonly in HIV-infected patients. Studies in STD clinics have demonstrated that HIV prevalence in patients with syphilis is as much as three times higher than the number of nonsyphilis patients in these settings.83, 89 However, the serologic manifestations and serologic response to treatment are largely unaffected by HIV status. Because of initial reports of treatment failure, many experts believed that all patients with syphilis, and especially patients with coexistent HIV infection, should be aggressively treated. Prospective studies by CDC investigators have demonstrated that in the majority of cases, such therapy is not necessary.95

Congenital Syphilis

In women who have untreated primary or secondary syphilis, the vertical transmission rate is estimated to be in the range of 75-95%.96 Late congenital syphilis is rarely seen in today’s antibiotic era. Transmission does occur transplacentally. Screening and treatment for congenital syphilis during pregnancy can effectively prevent this disorder, however. Thus congenital syphilis is completely preventable through screening, diagnosis, and treatment during the prenatal period. Therefore, congenital syphilis is considered a sentinel public health event and warrants an investigation. These cases occur almost exclusively in situations where there was inadequate prenatal care or where there are deviations from medical practice.

Treatment

Treatment of primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis is recommended to consist of benzathine penicillin.97 In patients who are allergic to penicillin, doxycycline may be used. Pregnant women with syphilis should be treated only with penicillin-based regimens. An increased number of case reports have described syphilis that is resistant to macrolides, so these medications are not recommended.98

Intervention approaches to syphilis control have long capitalized on the unique clinical aspects of the disease:

After treatment, an individual is noninfectious to sexual partners. With the advent of penicillin therapy, this concept has become a major tool in developing intervention strategies.

The long latency period from time of infection to time of infectiousness offers an opportunity for reducing secondary spread contacts. This understanding has been the basis of syphilis control programs based on partner notification and screening programs. In STD control programs, such practice is known as “surrounding the epidemic.”

The availability of an inexpensive diagnostic screening test (the syphilis serological test) allows widespread screening opportunities.

Because treatment during pregnancy prevents vertical transmission, prenatal screening and treatment programs have been established.

Role of the Syphilis Registry

All state and many local health departments in the United States maintain a syphilis “reactor registry.” Positive serological tests are reportable by law (by the laboratory); therefore, reporting is reasonably complete. Reactor registries compile test results and histories of treatment and can be useful in determining whether an individual patient had a previous serology and whether a positive test represents early latent, late latent, or previously treated disease. Useful epidemiological databases are also available to conduct operational and clinical research.

Partner Notification

Syphilis presents the prototype disease for the use of partner notification and presumptive treatment of partners.99 Although the empirical evidence strongly suggests that this strategy has been an effective approach in syphilis control, no randomized trials to date have been performed to demonstrate this relationship. Furthermore, partner notification is complicated in situations where large numbers of anonymous sex partners are the secondary spread contacts—a consideration that has been especially problematic in evaluation of disease intervention approaches in the homosexual bathhouses and in crack cocaine-associated epidemics.100, 101 In these situations, many public health intervention strategies have revolved around aggressive screening and presumptive treatment of partners.

Another intriguing aspect of syphilis is the relationship of immunology to infectiousness. The infectiousness of syphilis to sexual partners is largely concentrated in the primary and secondary stages. Individuals who are in late stages of syphilis (late latent, tertiary) are infected but not infectious and cannot be reinfected themselves during that time.102 Theoretically, then, it is possible to “saturate” a community to the point where there are so many latent infections that the pool of susceptibles decreases and “burns out” the outbreak. Paradoxically, in this situation, treating infected persons would revert many individuals back to a susceptible state.

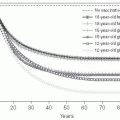

GENITAL HERPES INFECTION

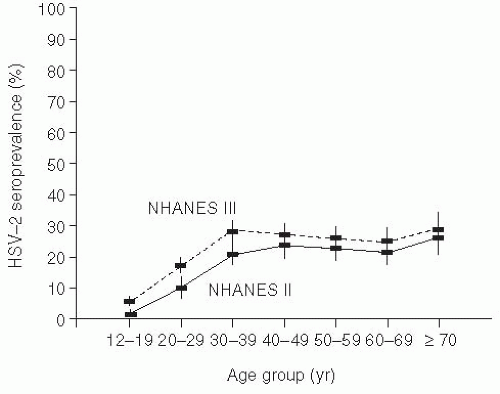

Genital herpes (from the Greek, meaning “to creep”) is typically due to herpes simplex type 2 (HSV-2), but may also be caused by HSV-1, and is widely prevalent in the adult U.S. population.103, 104, 105 and 106 Because of the problem in differentiating recurrences versus new infection, accurate incidence data are difficult to enumerate. Seroprevalence studies using type-specific research-grade assays have demonstrated that approximately 1 in 6 married sexually active Americans (40 million people) is infected with the herpes simplex virus; most of these individuals are asymptomatic (Figure 24-4).103, 105 Seropositivity has been associated with increased numbers of sexual partners, minority race, and socioeconomic status. Interestingly, even when adjusting for reporting artifacts in socioeconomic differences, African Americans still have substantially higher rates of HSV-2 seropositivity than other ethnic groups.106

An intriguing aspect of herpes epidemiology has been the shift in primary genital disease from HSV-2 to HSV-1.105 HSV-1 usually causes orofacial herpes (cold sores). HSV-2 still causes the bulk of prevalent genital infections, because recurrences due to HSV-2 are much more common. Nevertheless, studies from a variety of geographical regions have demonstrated that HSV-1 can cause just as many primary genital outbreaks as HSV-2. Two hypotheses have been suggested to explain this epidemiological trend. One hypothesis posits that increased HSV-1 genital infection results from increased oral sexual behavior. An alternative hypothesis is based on immunologic susceptibility. Individuals from previous generations were more likely to be exposed to HSV-1 as young children and, therefore, would be immune to genital HSV-1. In contrast, many of today’s young adults are susceptible to HSV-1 because of their lack of prior exposure as children.

Genital herpes is almost exclusively sexually transmitted.104 Approximately 90% of genital herpes is caused by HSV-2; 10% is caused by HSV-1. The reversed ratio is seen in cases of orofacial herpes. Orofacial herpes due to HSV-1 is transmitted as an upper respiratory tract infection, usually in early childhood.

HSV-1 and HSV-2 cause similar clinical syndromes at their respective mucosal sites. Acute infection with herpes simplex occurs after inoculation of virus to the mucosal site. Primary infection is often asymptomatic. When symptomatic cases occur, a mucosal or epidermal ulcer develops. Simultaneously,

viral particles enter the sensory nerve roots supplying the area and travel along the nerve axons to the dorsal root ganglia (DRG), where latency develops. For genital herpes, latency develops in the lumbosacral dorsal root ganglia; for orofacial herpes, the trigeminal ganglia are the source of the latent virus. When recurrences develop, viral particles begin replication in the DRG and travel centripetally to the periphery, exit at the mucosa or skin surface, and cause a repeat genital ulceration. Because of prior priming of the humoral and cellular immune systems, outbreaks are typically shorter than primary infections.

viral particles enter the sensory nerve roots supplying the area and travel along the nerve axons to the dorsal root ganglia (DRG), where latency develops. For genital herpes, latency develops in the lumbosacral dorsal root ganglia; for orofacial herpes, the trigeminal ganglia are the source of the latent virus. When recurrences develop, viral particles begin replication in the DRG and travel centripetally to the periphery, exit at the mucosa or skin surface, and cause a repeat genital ulceration. Because of prior priming of the humoral and cellular immune systems, outbreaks are typically shorter than primary infections.

Clinical Features

Genital herpes can occur at any mucosal exposed site (genitalia, rectum, and mouth). In primary disease, the ulceration develops 5-10 days after exposure; there may also be associated systemic signs, such as fever, myalgias, headache, and occasionally meningeal irritation.104 Recurrent herpes can develop at any time after the primary infection. In many settings, patients report a prodrome, which may consist of low-grade fever, pruritus, and tingling at the site of recurrence. Patients often report that they are able to feel the recurrence developing with nonspecific signs and symptoms, which is most likely related to irritation of the peripheral nerve roots.

Because many patients have asymptomatic primary infection, differentiation of a clinical first episode into primary disease or recurrence (in patients who have had an asymptomatic primary episode) is often not possible. In the research setting, primary infections are defined as an initial clinical episode with no serological evidence of prior infection. Most patients, however, when presenting with their initial episode, actually have serological evidence of prior infection.107 This condition is termed first clinical episode of recurrent disease. This distinction is often a very confusing point to clinicians and can be diagnosed by using type-specific serological tests. In some studies, more than 90% of persons with recurrent herpes diagnosed serologically could not identify a primary outbreak occurrence in the past. Symptomatic recurrences are less symptomatic and heal more rapidly than the primary episode. Recurrences are most frequent within the first year after primary infection and decrease thereafter. The factors involved in inducing recurrent episodes are not well characterized.104 Physical and physiological stresses have been classically cited as important cofactors, but there are few well-controlled studies that have been able to clearly elucidate these relationships.

Asymptomatic shedding plays a major role in transmission of HSV. This type of shedding occurs between clinical outbreaks, especially in the first few years after diagnosis.107 Initial culture studies of women with a recent diagnosis of primary herpes found that asymptomatic shedding occurred approximately 1% of the time. The asymptomatic culture-diagnosed shedding represents a potential infectious inoculum (approximately 104 viral particles). Further recent work with PCR demonstrated that shedding detectable by PCR occurred almost on a daily basis.108 Asymptomatic shedding rates are increased in persons with HIV or other immunodeficiencies.109

Diagnosis of Genital Herpes

Culture or other direct viral-specific tests from a lesion specimen establish the virological diagnosis of herpes. The highest yield of samples is that from the base of a wet genital ulcer or an aspirate of a vesicular eruption prior to breakdown. Serological testing using recombinant type-specific antigens is useful in ascertaining the presence of an IgG response to HSV-2.110 This response is typically detectable 4-6 weeks after exposure. The most commonly used commercial test has been shown to have acceptable sensitivity and specificity in African countries if the cutoff level is increased from 1.1 to 2.1.111

Persons who have positive cultures but who are seronegative are defined as having primary HSV infection. In contrast, persons with a first clinical outbreak, but who are HSV-2 seropositive, have recurrent infection. Serology can also be useful in defining whether an individual will benefit from suppressive therapy to reduce transmission.

Herpes Simplex in Pregnancy

The major concern with herpes simplex in pregnant women is preventing transmission to the neonate.112 Recurrent herpes during pregnancy is not a severe clinical problem unless lesions are present in the birth canal at time of delivery, which is an indication for a cesarean section. Another approach advocated by some obstetricians and perinatologists is routine cultures of the birth canal at parturition. If herpes simplex is diagnosed within 1-2 days, the infant may be started on prophylactic antiviral therapy.

The major risk in pregnant women is development of primary herpes during the last trimester of pregnancy. In those cases, as many as one-third of infants will be born with neonatal herpes syndrome, which may be fatal or lead to disability.104 Fetal infection is presumed to occur transplacentally. Primary infection during pregnancy can occur only if the

pregnant woman is previously uninfected and has an infected male partner. This is the type of setting where serologic diagnoses of previously unrecognized HSV are useful.

pregnant woman is previously uninfected and has an infected male partner. This is the type of setting where serologic diagnoses of previously unrecognized HSV are useful.

Treatment

In acute primary or recurrent genital herpes, treatment with nucleoside analogs results in more rapid healing of symptoms and more rapid resolution of viral shedding and of the ulcer.113 Treatment, however, is not curative. Acyclovir has been used for treatment since 1982, has a long track record of efficacy and safety, and has recently become available in generic formulations. Newer drugs for the treatment of genital herpes include famciclovir and valacyclovir, which offer the advantages of less frequent dosing.114

Suppressive Therapy

In individuals who have more than six recurrences per year or who are profoundly immunosuppressed and have recurrent disease (such as those with advanced HIV disease, transplant recipients, and patients undergoing chemotherapy), suppressive therapy is indicated. Suppressive regimens are more than 90% protective in preventing recurrences.113 Suppressive therapy also has a public health benefit. Studies of discordant couples (couples in which one partner is HSV-2 seropositive and the other is not) have shown that suppressive treatment of the infected partner, even if asymptomatic, reduces transmission of symptomatic disease by more than 90%; in addition, a 60% reduction of asymptomatic transmission occurs.115 This finding has profound impact because it sets a paradigm for treatment of an infected individual—not to benefit the patient, but to benefit an exposed second party (the sexual partner).

From an epidemiologic and control perspective, the following factors are associated with increased HSV transmission:

Asymptomatic viral shedding is implicated in more than half of the cases of new primary herpes transmission. Individuals with previous HSV-2 infection have asymptomatic shedding approximately 1-3% of the time, with an increased proportion of days that are positive in the year following the initial outbreak. From a clinical standpoint, there are no specific lesions or symptoms that are associated with asymptomatic shedding. Therefore, patients who are under the impression that if they are asymptomatic, they are unlikely to shed virus, can actually transmit the infection to their sexual partners.

Especially in women, herpes recurrences may be confused with other vaginal infections, especially “yeast infections.” This misclas-sification of herpes symptoms may lead to unprotected sexual encounters among misdiagnosed individuals, resulting in increased transmission.

Studies in monogamous couples in which one partner is infected and the other uninfected (discordant) indicate that approximately 11% of partners will seroconvert per calendar year of exposure.104 Studies have demonstrated that seroconversion may be less likely to occur in the face of antiviral therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree