Secondary Tumors of The Bladder

The bladder may be involved secondarily by tumors from adjacent sites such as the prostate, seminal vesicles, lower intestinal tract, and the female genital tract (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). These tumors more commonly involve the bladder by direct extension and can also metastasize to the bladder. Malignant lymphoma or leukemia may also secondarily involve the bladder as part of a more disseminated or systemic manifestation (see Chapter 12). Less commonly, the bladder may be involved by metastatic tumor from distant sites. The diagnostic problems posed for the pathologist in cases of secondary involvement vary according to the morphology of the primary neoplasm.

TUMORS INVOLVING THE BLADDER PRIMARILY BY DIRECT EXTENSION

Carcinomas of the prostate, rectosigmoid, and uterine cervix account for the most common primary neoplasms involving the bladder by direct extension, although other cancers such as those from the endometrium, ovary, appendix, and other segments of the colon may rarely directly involve the bladder (1, 3, 6, 7).

Prostate

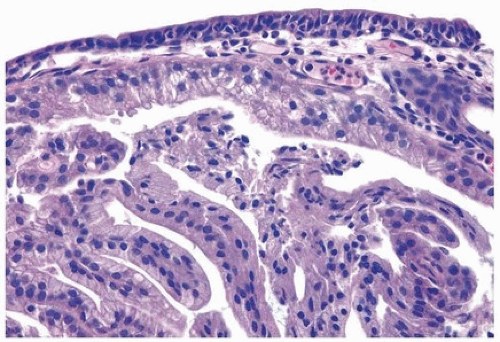

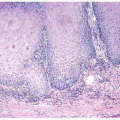

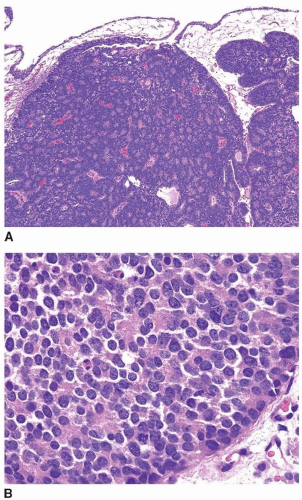

A common diagnostic problem is in differentiating on transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) between a poorly differentiated urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and a poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinoma (Figs. 13.1, 13.2, 13.3) (efigs 13.1-13.8). The therapy of these two diseases differs significantly, making the distinction between these two entities crucial. Most urothelial cancers grow in nests, whereas poorly differentiated prostate adenocarcinoma forms sheets of cells. The findings of infiltrating cords of cells or focal cribriform glandular differentiation are other features more typical of prostatic adenocarcinoma than urothelial carcinoma. Another useful differentiating feature in high-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma is a subtle attempt at cribriform gland formation. The tumor is so poorly differentiated that it cannot form true lumina, but there are rosette-like areas of cytoplasm in an attempt at glandular differentiation. Urothelial carcinoma lacks this morphology (Fig. 13.1). Cytologically, there are also several distinctions based

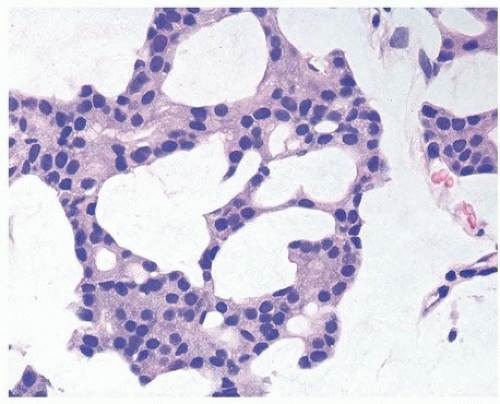

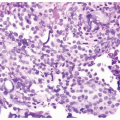

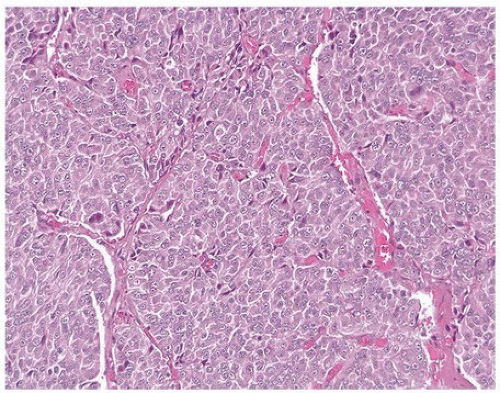

on routine H&E-stained sections. Even in poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinomas, there is typically relatively little pleomorphism or mitotic activity compared to poorly differentiated urothelial carcinoma. Poorly differentiated prostate adenocarcinomas may have enlarged nuclei and prominent nucleoli; yet usually, there is little variability in nuclear shape or size from one nucleus to another (Fig. 13.4). High-grade urothelial carcinomas often reveal marked pleomorphism occasionally with tumor giant cells. A subtler finding is that the cytoplasm of prostatic adenocarcinoma is often very foamy and pale imparting a “soft” appearance. In contrast, urothelial carcinomas may demonstrate hard glassy eosinophilic cytoplasm or more prominent squamous differentiation. In contrast to urothelial carcinoma

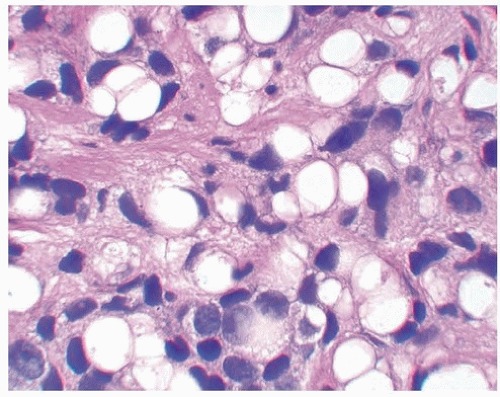

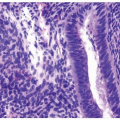

with glandular differentiation, adenocarcinoma of the prostate rarely contains mucin-positive signet cells. Some carcinomas of the prostate will have a signet-ring cell appearance, yet the vacuoles appear empty and do not contain intracytoplasmic mucin (Fig. 13.5) (8). Only a few cases of prostate cancer have been reported with mucin-positive signet cells (6, 7). Despite the above distinctions, there are often cases that overlap in their morphology. Although most urothelial cancers tend to grow in nests, in some cases, there are sheets of tumor. Another pitfall is that poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinoma can fall apart away from its blood supply, giving rise to pseudopapillary structures closely mimicking papillary urothelial carcinoma (Fig. 13.6) (9). Cytologically, rare cases of prostate adenocarcinoma

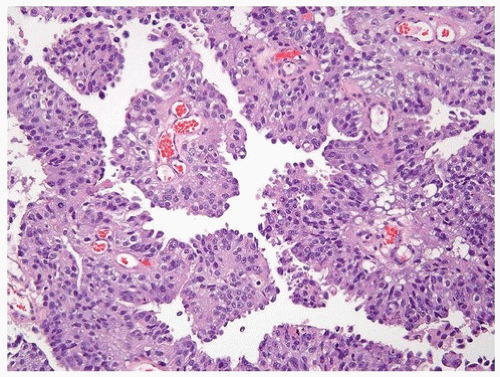

have marked pleomorphism identical to urothelial carcinoma (Fig. 13.7) (10). Presence of concomitant urothelial carcinoma in situ is helpful for proving a urothelial primary, although on very rare occasions, both urothelial and prostate cancers are seen in TURBT specimens. Almost 50% of cystoprostatectomy specimens performed for urothelial carcinoma also contain adenocarcinoma of the prostate (11). Therefore, the finding in a TURP of a small focus of well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the prostate should not necessarily influence whether a separate focus of poorly differentiated tumor is urothelial carcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the prostate.

on routine H&E-stained sections. Even in poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinomas, there is typically relatively little pleomorphism or mitotic activity compared to poorly differentiated urothelial carcinoma. Poorly differentiated prostate adenocarcinomas may have enlarged nuclei and prominent nucleoli; yet usually, there is little variability in nuclear shape or size from one nucleus to another (Fig. 13.4). High-grade urothelial carcinomas often reveal marked pleomorphism occasionally with tumor giant cells. A subtler finding is that the cytoplasm of prostatic adenocarcinoma is often very foamy and pale imparting a “soft” appearance. In contrast, urothelial carcinomas may demonstrate hard glassy eosinophilic cytoplasm or more prominent squamous differentiation. In contrast to urothelial carcinoma

with glandular differentiation, adenocarcinoma of the prostate rarely contains mucin-positive signet cells. Some carcinomas of the prostate will have a signet-ring cell appearance, yet the vacuoles appear empty and do not contain intracytoplasmic mucin (Fig. 13.5) (8). Only a few cases of prostate cancer have been reported with mucin-positive signet cells (6, 7). Despite the above distinctions, there are often cases that overlap in their morphology. Although most urothelial cancers tend to grow in nests, in some cases, there are sheets of tumor. Another pitfall is that poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinoma can fall apart away from its blood supply, giving rise to pseudopapillary structures closely mimicking papillary urothelial carcinoma (Fig. 13.6) (9). Cytologically, rare cases of prostate adenocarcinoma

have marked pleomorphism identical to urothelial carcinoma (Fig. 13.7) (10). Presence of concomitant urothelial carcinoma in situ is helpful for proving a urothelial primary, although on very rare occasions, both urothelial and prostate cancers are seen in TURBT specimens. Almost 50% of cystoprostatectomy specimens performed for urothelial carcinoma also contain adenocarcinoma of the prostate (11). Therefore, the finding in a TURP of a small focus of well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the prostate should not necessarily influence whether a separate focus of poorly differentiated tumor is urothelial carcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the prostate.

FIGURE 13.1 A: Metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma with poor cribriform glandular formation resembling rosettes undermining urothelium. B: Higher magnification of Figure 13.1A showing rosette-like structures. |

FIGURE 13.4 Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the prostate lacking pleomorphism typically seen with urothelial carcinoma. |

Consequently, in a poorly differentiated tumor involving the bladder and prostate without any glandular differentiation typical of prostate adenocarcinoma, the case should be worked up immunohistochemically. Approximately 90% of poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinomas

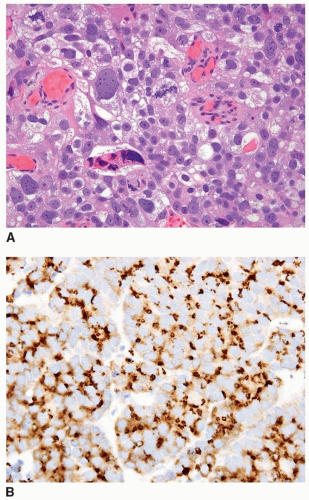

show PSA and PSAP staining although it may be focal (12, 13, 14). In the setting of a poorly differentiated carcinoma where the differential diagnosis is prostatic adenocarcinoma versus urothelial carcinoma where PSA and/or PSAP is negative and urothelial markers (see below) are negative, then other prostate markers should be utilized. Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and androgen receptor (AR) have lower specificity and are not recommended (15, 16, 17, 18, 19). The two prostate markers that are more sensitive than PSA and are just as specific are prostein (P501S) and NKX3.1 (15). P501S has the benefit of distinctive clumpy granular immunoreactivity, and NKX3.1 is a very sensitive and specific nuclear antibody.

show PSA and PSAP staining although it may be focal (12, 13, 14). In the setting of a poorly differentiated carcinoma where the differential diagnosis is prostatic adenocarcinoma versus urothelial carcinoma where PSA and/or PSAP is negative and urothelial markers (see below) are negative, then other prostate markers should be utilized. Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and androgen receptor (AR) have lower specificity and are not recommended (15, 16, 17, 18, 19). The two prostate markers that are more sensitive than PSA and are just as specific are prostein (P501S) and NKX3.1 (15). P501S has the benefit of distinctive clumpy granular immunoreactivity, and NKX3.1 is a very sensitive and specific nuclear antibody.

FIGURE 13.7 A: Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the prostate with marked pleomorphism mimicking urothelial carcinoma. B: Tumor is positive for P501S verifying prostate origin. |

Some of the most commonly currently used antibodies to label urothelial carcinoma are not recommended, and others lack specificity. Finally, CK7 and CK20 are of limited utility in this differential given that they may both be positive in a subset of prostatic adenocarcinoma (20, 21). High molecular weight cytokeratin and p63 are positive in approximately two thirds of urothelial carcinoma but can be focally expressed in prostate adenocarcinoma, especially poorly differentiated prostate cancer where urothelial carcinoma is in the differential diagnosis (15, 22). Also, HMWCK labels squamous epithelia including areas of squamous differentiation in posttherapy recurrent prostate carcinoma lesions (10). Although highly specific for urothelial differentiation, uroplakin III and the newer uroplakin II lack sensitivity in high-grade invasive urothelial carcinoma, and we have not found them to be useful in this differential diagnosis (23, 24). Thrombomodulin suffers from the same lack of sensitivity, although it is fairly specific in terms of not labeling prostate cancer (15, 25, 26). The best current urothelial marker in the differential diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma versus prostate adenocarcinoma is GATA3. In the two largest studies by Liu et al. (28) and Miettinen et al., (27) 86% and greater than 90% of urothelial carcinomas were positive for GATA3, respectively. The nuclear staining is usually diffuse in >50% of cells. In rare cases, prostatic adenocarcinoma can be positive for GATA3 (27, 28, 29).

In summary, the ISUP-recommended immunohistochemistry protocol to distinguish prostate adenocarcinoma from urothelial carcinoma is as follows (19).

1. Option to use PSA as a first test to identify PCa and GATA3 to identify urothelial carcinoma.

2. If GATA3 is not available, then high molecular weight cytokeratin (HMWCK) and p63 can be used.

3. If the tumor is PSA positive with intense staining and HMWCK and p63 negative, the findings are diagnostic of prostatic adenocarcinoma.

4. If the tumor is equivocal/weak/negative for PSA and negative/focal for p63 and HMWCK, then staining for P501S, NKX3.1, and GATA3 must be performed. Some experts also include PAP in this second round of staining.

5. If the tumor is negative for PSA and diffusely strongly positive for p63 and HMWCK, the findings are diagnostic of urothelial carcinoma.

6. If the tumor is negative for PSA and moderately to strongly positive for GATA3, it is diagnostic of urothelial carcinoma.

7. Laboratories should be encouraged to use GATA3 for urothelial carcinoma and add P501S and NKX3.1 as prostate markers in addition to PSA, p63, and HMWCK.

8. If GATA3, P501S, and NKX3.1 are not available in equivocal cases, they should be sent out for consultation to laboratories with these antibodies.

Colorectal

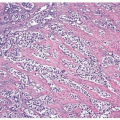

Colorectal carcinoma most commonly involves the bladder by direct invasion, but also by discontinuous metastases. Distinction of a colon versus a bladder primary adenocarcinoma is difficult to impossible, because colonic tumors can even involve the bladder mucosa and secondarily colonize it to create a villous architecture that would suggest a primary bladder tumor (30, 31) (Figs. 13.8, 13.9, 13.10, 13.11) (efigs 13.9-13.19). Urothelial carcinoma with enteric differentiation may show obvious conventional urothelial carcinoma histology or urothelial CIS, which may help to establish a bladder primary. A history of high-grade, high-stage colon cancer is important, and, if present, an adenocarcinoma in the bladder with enteric histology should be considered as a metastasis. Immunohistochemical studies are not definitive as “intestinal” markers, such as CDX2, villin, are variably expressed in adenocarcinoma of the bladder (31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36). The one exception is that strong diffuse nuclear beta-catenin expression is highly suggestive of adenocarcinoma of the colon, as only rare cases of bladder adenocarcinoma express focal weak nuclear positivity. Most bladder adenocarcinomas express both CK7 and CK20, in contrast to typical adenocarcinoma of the colon, which

is often negative for CK7 (31, 32, 33, 36). GATA3 is typically not positive in enteric subtype of bladder adenocarcinoma such that it is not that useful in this differential diagnosis, and uroplakin can be positive in colorectal adenocarcinoma (37, 38, 39). None of the immunohistochemical studies are sufficiently diagnostic to be definitive as to the source of the adenocarcinoma. Consequently, in the setting of an adenocarcinoma with enteric morphology involving the bladder, it is best to state: “Although this tumor may be primary in the bladder, an intestinal adenocarcinoma with spread to the bladder should be excluded on clinical grounds.” The potential of

subjecting a patient to radical cystectomy for colorectal cancer involving the bladder, erroneously thought to be a primary adenocarcinoma of the bladder, justifies a routine recommendation of imaging studies or colonoscopy to exclude an intestinal tumor in the setting of an adenocarcinoma with enteric morphology on bladder biopsy.

is often negative for CK7 (31, 32, 33, 36). GATA3 is typically not positive in enteric subtype of bladder adenocarcinoma such that it is not that useful in this differential diagnosis, and uroplakin can be positive in colorectal adenocarcinoma (37, 38, 39). None of the immunohistochemical studies are sufficiently diagnostic to be definitive as to the source of the adenocarcinoma. Consequently, in the setting of an adenocarcinoma with enteric morphology involving the bladder, it is best to state: “Although this tumor may be primary in the bladder, an intestinal adenocarcinoma with spread to the bladder should be excluded on clinical grounds.” The potential of

subjecting a patient to radical cystectomy for colorectal cancer involving the bladder, erroneously thought to be a primary adenocarcinoma of the bladder, justifies a routine recommendation of imaging studies or colonoscopy to exclude an intestinal tumor in the setting of an adenocarcinoma with enteric morphology on bladder biopsy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree