(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

The sacrum may be involved by a primary tumor; such as a chordoma; by direct extension from a tumor of adjacent tissues, such as rectal adenocarcinoma; or by metastatic disease. Resection of the sacrum is indicated usually for primary tumors of this bone or for tumors involving the sacrum by direct extension from adjacent tissues, when the tumor can be resected completely by including the sacrum in the plan of operative extirpation.

When transabdominal exposure and dissection in front of the tumor are needed, the patient is usually placed in a right lateral position. The left flank and the abdominal wall are prepared and included in the draping, which allows a lower midline incision or possibly a left flank incision, to enter the abdomen and work around the tumor mass from inside the peritoneal cavity. The flank incision is rarely used, however, because if a colostomy is needed, the flank incision may be found to occupy the site to be traversed by the colostomy. Therefore, the lower midline incision, starting from above the umbilicus and proceeding to the left of the umbilicus and down the midline to the pubic symphysis, is preferable. By entering the peritoneal cavity, one may also examine for evidence of metastatic disease, which would negate the benefit of doing the planned operation. The sigmoid may be separated from the lateral peritoneal reflection by incising the peritoneum along the white line (Toldt’s line). The ureter is exposed and the rectosigmoid is mobilized to the extent allowed by the perceived involvement by the rectal tumor of the anterior surface of the sacrum. Preoperative stenting of the ureters is advisable. The dissection in the posterior wall of the rectum should be done carefully so as to avoid entering the area of extension of the rectal tumor in the sacrum, but the anterior wall of the rectum is exposed as far as one can safely go.

After completion of transabdominal dissection, the abdominal incision is left open but covered with wet laparotomy pads and other sterile drapes. One continues with a longitudinal posterior incision over the sacrum, with the patient remaining in a right lateral position. The approach is somewhat awkward but provides the opportunity of bilateral abdominal and sacral approach simultaneously as needed during various stages of the procedures. In the abdominal sacral approach, used for resection of low rectal tumors (which are usually benign or of low-grade malignancy), a transverse incision has been used over the lower sacrum, with removal of the coccyx and perhaps the S5 vertebra providing good exposure of the area of the mid-rectum for resection of a tumor that requires only a conservative excision. This approach could also be used to provide exposure for a low rectal anastomosis.

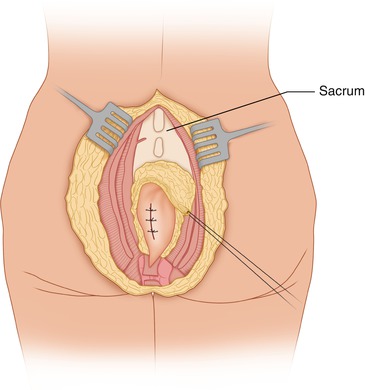

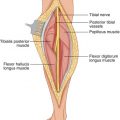

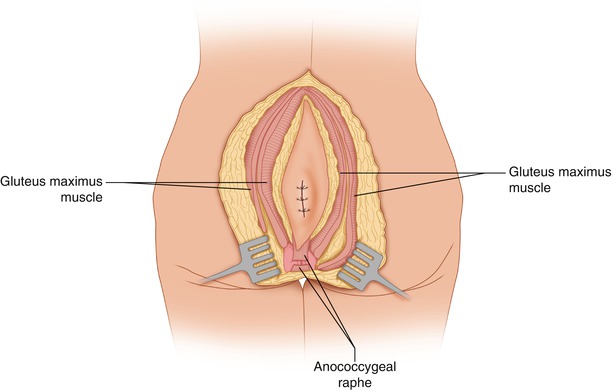

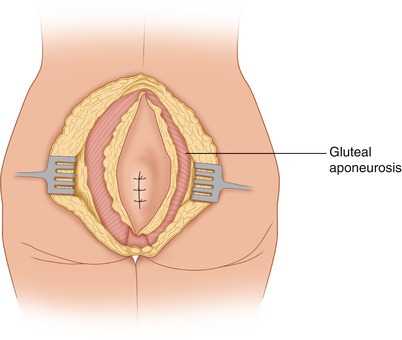

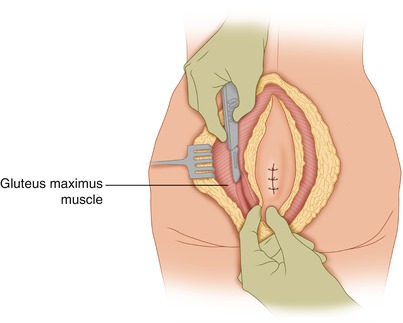

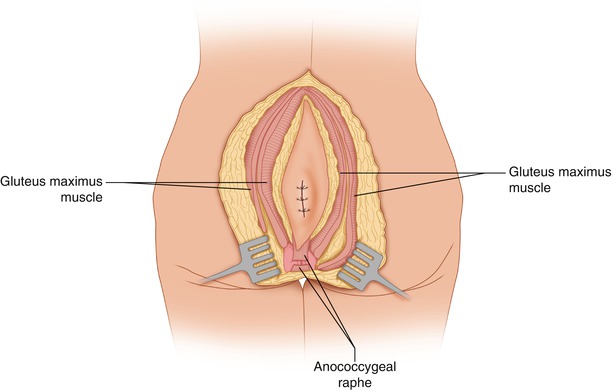

For small tumors without significant protrusion anteriorly, tumors following radiation or surgery, or large tumors that are not protruding anteriorly, the patient may be placed preferably in a prone position. With the patient in a prone position, a longitudinal incision is made over the middle of the sacrum, which provides better exposure for tumors arising in the sacrum. The incision might be slightly curved at the lower end, around the posterior quarter of the perianal circumference, to provide extra length, facilitate skin closure, and improve the exposure of the anococcygeal ligament. An elliptical incision should be made around the previous biopsy incision. Flaps are developed to the right and left of midline until the fibers of the gluteus maximus are clearly exposed at their origin from the side of the sacrum (Fig. 45.1). The gluteal fascia covering the gluteus maximus is incised and the muscle fibers of this muscle are divided off their origin in the sacrum (Fig. 45.2). In the inferior end of the incision, below the tip of the coccyx, the anococcygeal raphe is incised and the precoccygeal space is entered with blunt finger dissection (Fig. 45.3). The fibers of the gluteus maximus are divided close to their origin from the sacral surface. This dissection is helped by simultaneous feedback from the finger inside the presacral space adjacent to the edge of the sacrum and by the visible dissection on the lateral aspect of the sacrum on the same side. The origin of the sacrotuberous ligament is divided on both sides of the sacrum, and the sacrospinous ligament is divided at a higher and more anterior level, with care to displace laterally the pudendal nerve and vessels. Although these structures exit the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis, they take a turn around the sacrospinous ligament and reenter the lesser pelvis on the lateral wall of the ischiorectal fossa covered by the fascia of the obturator internus.

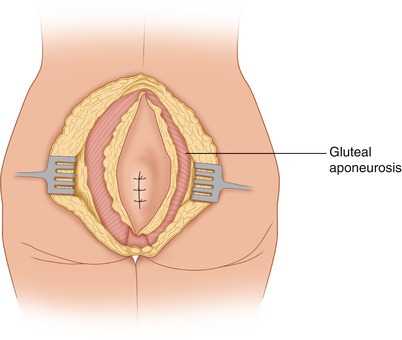

Fig. 45.1

An elliptical incision has been made around the previous biopsy incision for a sacrococcygeal chordoma. Flaps are developed to the sacral edges

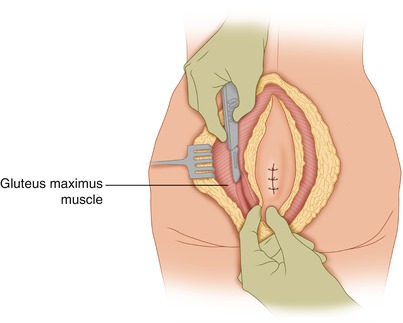

Fig. 45.2

The muscle fibers of the gluteus maximus are divided as they arise at the sacral edge on each side

Fig. 45.3

The origin of the gluteus maximus from each side of the sacrum has been divided, as have the sacrotuberous ligament and the anococcygeal raphe

A point is reached where one feels the lower border of the sacroiliac joint, in effect the lower border of the sacroiliac ligament. With blunt dissection on the anterior surface of the sacrum, as well as sharp dissection as needed, the rectum is separated from the sacrum in the area where the plane appears to be free of tumor involvement. If the tumor bulges anteriorly from the sacrum or if it protrudes posteriorly into the sacrum from the rectum, one should be able to feel this area of the tumor and thus avoid a forced entry in the junction of the sacrum and the tumor. Instead, one proceeds dissecting with caution on the sides of this connection with tumor between the sacrum and the rectum, until the proximal extent of the tumor’s involvement of the sacrum is reached. One dissects then above the proximal extent of the tumor. Meanwhile, the posterior surface of the sacrum has been exposed (Fig. 45.4). The bone itself is exposed by incising the ligaments covering the sacrum transversely at the desired level. As the proximal posterior surface of the sacrum is exposed, if it appears to be free of tumor and both sides of the sacrum at the same level and the anterior surface of the sacrum are free, one may divide the sacrum using an osteotome or a Gigli saw (Fig. 45.5). From the posterior aspect of the sacrum, it is difficult to determine the exact level where one is about to amputate through the bone, and it is also difficult even with an anteroposterior x-ray using a metallic marker for greater presumed accuracy of the level of the proposed division of the sacrum, considering that the sacrum is not disposed in a vertical plane, but rather in a plane inclined posteriorly. A lateral view of the sacrum is obscured by the superimposition of the adjacent iliac bones. As a practical rule, however, if one can cut across the sacrum in a straight line, one is below the lower sacroiliac ligaments and therefore at a level below the S3 vertebra. It is thus safe to cut through the sacrum, preserving the roots (S2–S3) to the pudendal nerves bilaterally, which have to do with control of the sphincters and with erection in men. If the tumor requires a higher division of the bone, however, one would have to use oblique cuts into the sacroiliac joint bilaterally, from the lower edge of the sacroiliac joint and sacroiliac ligaments, in order to reach a higher level, given that the first two sacral vertebrae are attached to the iliac bone through the sacroiliac joints and ligaments (Fig. 45.5). If an osteotome is used for that purpose, the surgeon has no control of exactly what is being cut in the sacral canal. With this technique, the subarachnoid space may be entered, with leakage of cerebrospinal fluid. The dura is sutured, but the postoperative course may be complicated by wound infection and/or the effects of denervation of the pudendal nerves, including incontinence, as one might expect with a high division of the sacrum (S1–S2). Urinary incontinence may be controlled by the patient through self-catheterization with a straight catheter three times a day. Fecal incontinence seems to be less of a problem because there is a tendency for constipation, and evacuation of the stool from the rectal ampulla is aided with enemas and occasionally digital disimpaction. The use of a more discriminating instrument is recommended to cut through the sacrum above the level of the lower border of the S3 vertebra from the posterior surface. For example, a rongeur can be used to enter the sacral canal, and a Kerrison rongeur can be used to open the sacral canal widely from the midline in a lateral direction, at the approximate level where one wishes to divide the bone (Fig. 45.6). The upper extent of the tumor is visualized, along with any nerve roots that may be proceeding obliquely from the midline in an inferolateral direction. Such roots can be displaced superiorly, traced in their continuity to the sacral nerve roots, and preserved, provided of course that this is allowed by the extent of the tumor. When the sacral canal is opened, it is possible to visualize the lower end of the dural sac (S2 vertebra) and to displace it superiorly with a pledget. The higher sacral nerve roots also can be identified (at the anterior aspect of sacrum) and slightly displaced laterally and superiorly to their point of continuity with the pudendal nerve. Once this is done, the anterior “plate” (fused bodies) of the sacrum may be divided using the osteotome, having a finger on the anterior sacral surface to guide the direction of cutting with the osteotome. With this method, one may be able to divide the sacrum through the middle of the second sacral vertebra and yet preserve the second nerve roots bilaterally, possibly along with one of the third sacral roots (Fig. 45.7).