(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

The abdominoinguinal incision is in a sense a derivative of the radical groin incision, in which the retroperitoneal space in entered through a lateral incision dividing the anterolateral abdominal wall muscles and then the inguinal ligament lateral to the femoral artery. Division of the inferior epigastric artery and vein at their origin follows, and the iliac fossa and the iliac vessels are exposed. The exposure is not nearly as adequate as in the abdominoinguinal incision, however. With the radical groin incision, the approach is from lateral to medial, in terms of ligating and dividing the inferior epigastric vessels, whereas in the abdominoinguinal incision, the approach is from medial to lateral, and of course with the abdominal part of this incision, one can get ample exposure in the abdominal cavity and extend the incision as proximally as needed, all the way up to the xiphoid.

In Chap. 41, the application of the abdominoinguinal incision in sarcomas of the iliac fossa (some extending behind the inguinal ligament to the groin), sarcomas involving the iliofemoral vessels, massive metastases to the iliac, obturator nodes, and pelvic tumors extending to the pubic bone and adductors, was described. However, there is a group of large pelvic tumors starting from the lesser pelvis, which extend laterally to fill in the lesser pelvis so that there is no room for maneuvers between the sides of the tumor and the walls of the pelvis. These tumors tend to overflow the boundaries of the lesser pelvis. Tumors with this presentation have a significant visceral component often involving more than one viscera. Briefly, tumors in Chap. 41 were of the parietal pelvis, while tumors in this chapter belong to the visceral pelvis, although obviously there is some overlapping between the two.

The abdominoinguinal incision is simply a method of exposure for the removal of pelvic tumors with fixation. As with other types of incision or exposure, recurrence rates vary according to factors such as the biologic aggressiveness of the tumor, the margin of resection, and the adjuvant modalities used. Compared with hemipelvectomy, an abdominoinguinal incision may not provide as large a surgical margin in a lateral and inferior direction, but the abdominoinguinal incision may provide a better margin in a superior and medial direction through the abdominal part of the incision. Furthermore, the abdominoinguinal incision has a wider range of application and preserves normal function for both lower extremities, whereas hemipelvectomy involves a high amputation of the extremity together with the involved hemipelvis. This incision has also been used successfully for resection of colon tumors with fixation, such as a tumor in the sigmoid fixed to the iliac fascia or a tumor in the cecal area fixed to the iliopsoas muscle, with or without infiltration of the ureter and ulceration through the anterior abdominal wall. Such cases that have been resected with the abdominoinguinal incision have done well on long-term follow-up because if tumors with such extensive local infiltration and growth lack any evidence of metastasis to the liver or elsewhere, as a rule they are biologically less aggressive. If these tumors are resected with adequate surgical margins, patients tend to do well and some are cured.

In closing this incision, the femoral vessels should be covered with the sartorius muscle as in groin dissection so that in the event of skin edge necrosis, the vessels will not be exposed. The postoperative course and the healing of the incision is usually unremarkable. However, there is a tendency for skin edge necrosis in the corner between the transverse part of the incision and the vertical part in the groin, which is more likely to occur when there is a previous incision in the adjacent skin or when the deep iliac circumflex vessels have to be ligated and divided. The following examples illustrate some principles associated with the resection of pelvic tumors and the use of the abdominoinguinal incision.

Case 1: Hemangiopericytoma Involving the Lower Abdominal Wall

A 65-year-old woman had a large hemangiopericytoma in the lesser pelvis (Fig. 42.1). This tumor had been operated on twice before, but the resection was abandoned because of excessive bleeding. The CT scan showed a large tumor fixed to the left side of the pelvis. The blood supply of the tumor derived primarily from the left internal iliac artery but also came from many other vessels. On exploration, the left common iliac artery was exposed and a ligature was placed on the internal iliac artery. The left round ligament, fallopian tube, and broad ligament were divided close to the body of the uterus. The left side of the dome of the bladder and the upper sigmoid colon were separated from the tumor, but further dissection between the tumor and these structures, specifically the body of the uterus, encountered severe bleeding due to multiple venous and arterial branches. Resection of the tumor was therefore abandoned. An arterial catheter was placed in the left internal iliac artery below the ligature, which had been placed proximally on this artery. Intra-arterial chemotherapy with cisplatin was administered postoperatively, but the tumor increased in size.

Fig. 42.1

A highly vascular pelvic tumor is shown on the arteriogram

At exploration 2 months later, the extension of the tumor was found to involve the inner surface of the left lower abdominal wall. This extension of the tumor was separated from the abdominal wall at reoperation, and the midline incision was extended to the left groin as per an abdominoinguinal incision. Thus we were able to expose the femoral, external iliac, and common iliac vessels. The sigmoid colon was divided above the tumor, and the sigmoid and its mesentery were left attached to the tumor. A right abdominoinguinal incision was also performed in order to expose the right external iliac and common iliac vessels, as well as the right internal iliac artery. A ligature was placed on the right internal iliac artery, and the right round ligament, fallopian tube, broad ligament, and uterine artery were divided. The vagina below the cervix was divided in order to remove the uterus en bloc with the adjacent hemangiopericytoma. The tumor remained attached to a large area of the left side of the pelvis, but as all the major arterial supply to the tumor (ie, the left internal iliac and right internal iliac arteries) had been ligated and the sigmoid mesenteric branches had been divided, we proceeded to sharply divide the plane between the tumor and the wall of the lesser pelvis. The result was severe hemorrhage that could not be controlled with sutures. A large packing controlled the bleeding, which was all venous. A descending colostomy was performed. The packs were removed 72 h later and the patient recovered. On long-term follow-up, she remained free of tumor.

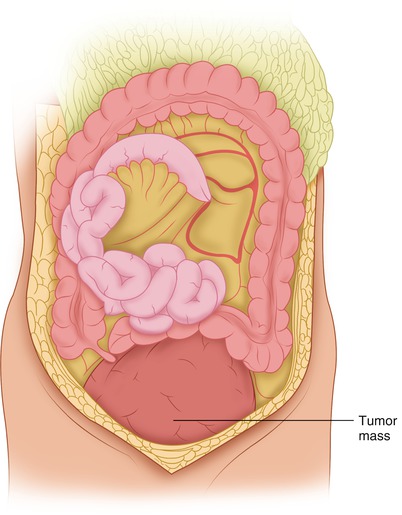

Case 2: A Large Liposarcoma Infiltrating the Sigmoid and Bladder

A 74-year-old man with a large liposarcoma in the pelvis had been operated upon twice elsewhere. Both times, the tumor was called unresectable. He was treated with chemotherapy using various agents, but the tumor grew to the point that it obstructed both ureters, and bilateral nephrostomy tubes were placed. The large tumor mass was palpable on physical examination and was also visually evident. Through a midline incision, adhesions were lysed and the small bowel and its mesentery were separated from the tumor (Fig. 42.2), which filled both the greater and lesser pelvis. The parietal peritoneum lateral to the descending colon was incised (Fig. 42.3). The left ureter was exposed and found to be dilated (Fig. 42.4). The left common iliac artery and the external iliac artery were exposed. The left internal iliac artery was ligated (Fig. 42.4). The right parietal peritoneum was incised (Fig. 42.5). The right ureter, which was also dilated, was exposed by retracting the cecum medially. The tumor, which was projecting more on the right side, reached all the way down behind the inguinal ligament and was obscuring the exposure of that area (Fig. 42.6). The incision was extended to the right groin in the manner of the abdominoinguinal incision, achieving excellent exposure for separation of the tumor from the iliac vessels (Fig. 42.7). A ligature was placed on the right internal iliac artery (Fig. 42.8), and then we mobilized the tumor en bloc with the sigmoid and the upper rectum (Fig. 42.9). The sigmoid mesentery was dissected (Fig. 42.10), and the proximal sigmoid and its mesentery were divided (Fig. 42.11). The presacral space was entered and the rectosigmoid was mobilized (Fig. 42.12). The right ureter was dissected to close its point of entry into the bladder (Fig. 42.13). The posterior wall of the bladder was extensively infiltrated by the tumor (Fig. 42.14). It was then possible to resect the tumor en bloc with the rectosigmoid, the urinary bladder, and the distal ureters (Fig. 42.15). An ileal loop bladder was then fashioned (Fig. 42.16). The lower descending colon was anastomosed to the rectum, and a protective right transverse cutaneous loop colostomy was performed (Fig. 42.17). The patient survived for 6 years, but died following an unsuccessful operation elsewhere for presacral recurrence of the tumor.