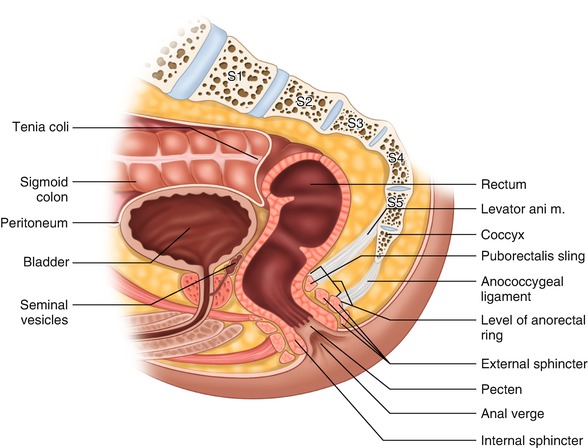

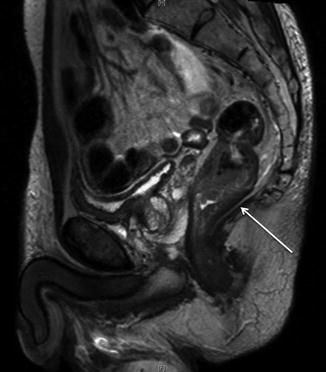

Fig. 1.1

MRI of pelvis (sagittal, T2 sequence), male, ulcerated tumor in the posterior, lower rectum (arrow)

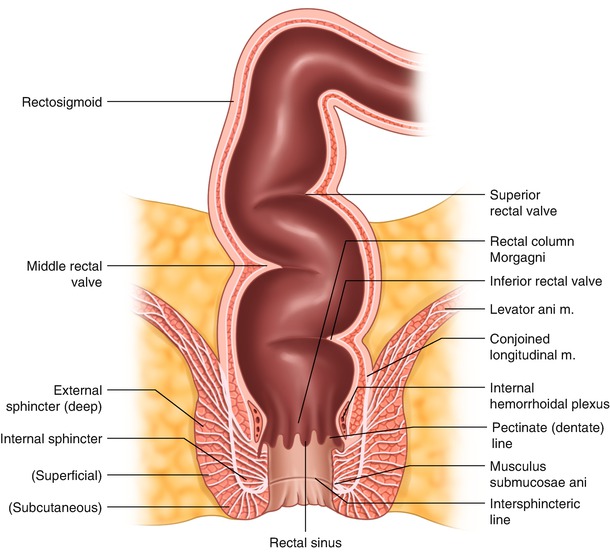

Fig. 1.2

Rectal anatomy , lateral view

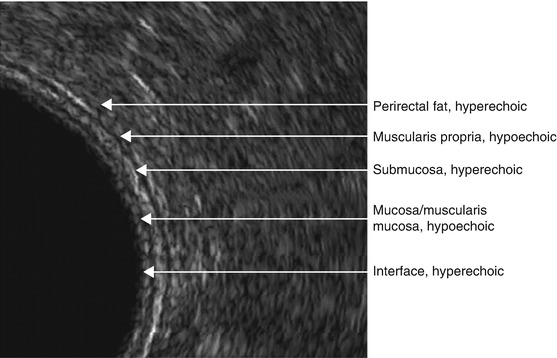

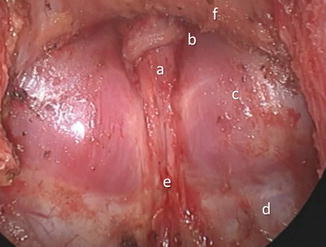

Fig. 1.3

Rectal anatomy , AP view

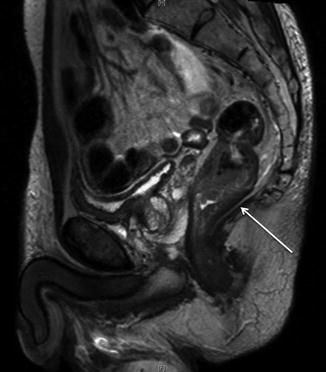

Fig. 1.4

Endorectal ultrasound , layers of the rectal wall and the mesorectum

Endoscopically, the rectum is wider than the rest of the left colon. The rectum’s most distal part, the ampulla, is the widest, allowing for safe retroflexion of the flexible endoscope. In linear measurements, this part, when distended, is at least two to three times wider than the width at the anorectal junction. Additionally, the change in size between these two segments takes place in a very short distance, an important fact to consider during bowel stapling. The high accommodation properties of the rectum result in increased thickness of the non-stretched rectal wall. On average, three internal folds can protrude into the lumen of the rectum (valves of Houston) when the bowel is moderately distended; however, anatomical variations exist [8] (Fig. 1.3). These folds involve approximately 25–75% of the circumference and are the result of increased muscular fiber concentration in the circular layer of the bowel wall. The lowest valve is located approximately 3–5 cm above the anorectal junction . The second valve (Kohlrausch’s plica) is on the opposite side and often corresponds with the level of the anterior peritoneal reflection in an individual of average weight and height. The third valve is located on the left side. Together, all three valves create several mild curvatures that need to be negotiated during endoscopic exam or transanal insertion of the stapler. Inadvertent incorporation of the folded valve into the staple line during transanal stapling may result in anastomotic leak.

Still more important curves to consider, however, are those seen on lateral projection, including a 90-degree (anorectal) angle between the ampulla and the anal canal, and a gentler anterior curve along the concavity of the sacrum. The sharp anorectal angle forms the “posterior rectal shelf ” and contributes to fecal continence. It can be easily appreciated upon digital exam (Fig. 1.2). Unfortunately, it can also make it difficult to properly evaluate the posterior cancers of the very distal rectum during transanal sonography. In this case, it is difficult to orient the ultrasound beam perpendicularly to the posterior wall of the most distal rectum . Both angles may need to be negotiated safely during transanal stapler insertion.

Mesorectum

In the majority of individuals, the circumference of the rectal tube, excluding significant portion of the anterior aspect, is surrounded by adipose tissue called mesorectum (Fig. 1.5). Initially, the term mesorectum was considered a misnomer [9]. Today, it is accepted as a proper term describing a package of adipose tissue surrounding the rectal tube in a distinct fascial layer (fascia propria of the rectum or FPR ). The mesorectum contains vessels, lymphatics, and lymph nodes as well as minor nerve fibers. In obese individuals, the lower half of the rectum is often completely surrounded by the mesorectum due to abundant anterior fat deposits.

Fig. 1.5

Rectum after total mesorectal excision (peritoneal reflection marked with arrow)

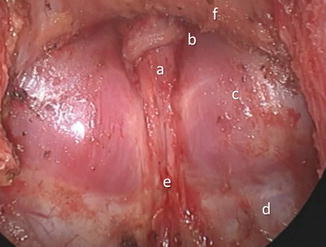

The significance of the mesorectum is mainly related to the lymph nodes, which are frequently the site of locoregional tumor spread and should be resected en bloc along with the involved segment of the rectal tube [1]. Clinically, the average number of lymph nodes within the entire mesorectal specimen can vary anywhere between 5 and 20 (up to 40 in some anatomical studies) and can be reduced after preoperative radiation therapy [10–13]. In its distal part, the mesorectum tapers out and frequently disappears in thin individuals (Fig. 1.6). This allows the rectal tube to be in direct apposition to the convexity of the pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus (levator ani) muscles and the concavity (groove) of the anococcygeal raphe (Fig. 1.7).

Fig. 1.6

MRI, T2 sequence, thin male; thinned out (absent) mesorectum in the lower aspect of the posterior rectum

Fig. 1.7

Posterior pelvis after total mesorectal excision: a rectal stump, b pubococcygeus muscle, c dome of the iliococcygeus muscles, d coccygeus muscle, e anococcygeal raphe, f anterior pelvic structures covered by an intact Denonvilliers’ fascia

Fascial Layers of the Pelvis

Fascia Propria of the Rectum

The fascia propria of the rectum (FPR) is also referred to as mesorectal fascia, investing fascia, or visceral pelvic fascia. It creates a thin envelope surrounding the mesorectum and the anterior part of the bowel not covered by the mesorectum, thus forming a distinct anatomical package. This package can be surgically dissected out in toto during total mesorectal excision. Moving cephalad, the mesorectal fascia is an equivalent of the mesocolic fascia that covers the left colon. It fuses with the endopelvic fascia and the presacral fascia.

Endopelvic Fascia

The endopelvic fascia is a distinct fascial layer that covers the floor and sidewalls of the entire pelvis. In obese individuals, a certain amount of adipose tissue can be found underneath the endopelvic fascia or even in between its particular layers (Fig. 1.8). On the other hand, in a thin patient, it can be translucent (Fig. 1.9). In the lateral aspects of the pelvis, the endopelvic fascia extends to the sides, covering the origin of the levator ani muscles at the tendinous arch along the internal obturator muscle.

Fig. 1.8

Endopelvic fascia in a patient with visceral obesity, presacral segment, upper half of total mesorectal excision

Fig. 1.9

Endopelvic fascia in a thin patient, presacral segment, upper half of total mesorectal excision. Visible presacral structures: veins, arteries, sympathetic ganglia

Presacral Fascia

The presacral fascia lines the posterior aspect of the cylindrical mesorectal compartment in front of the sacrum. In the posterior midline, it covers the promontory as a continuation of the abdominal Toldt’s fascia into the pelvis (Fig. 1.8). Descending deeper into the pelvis, this fascia lines the midline portion of the sacrum, spreading anteriorly and laterally in the arcuate fashion in order to cover the medial portion of the piriformis muscles, the sacral foramina containing sacral nerves roots, and the midline and posterior portion of the levators.

Denonvilliers’ Fascia

In the anterior aspect of the extraperitoneal rectum, extending slightly above the peritoneal reflection, there is a distinct layer of fibroelastic tissue called the Denonvilliers’ fascia. It is a trapezoidal sheet separating the mesorectal compartment from the anterior pelvic structures (Fig. 1.10). In men, Denonvilliers’ fascia stretches in a concave fashion between both pelvic sidewalls as a cover of the anterior pelvic compartment, which includes the bladder, seminal vesicles, vasa deferentia, ureters, prostate, and both neurovascular (genitourinary) bundles. In women, Denonvilliers’ fascia stretches in a concave fashion from both pelvic sidewalls covering the posterior wall of the vagina as well as the genitourinary neurovascular bundles.

Fig. 1.10

Denonvilliers’ fascia , male patient, level of seminal vesicles (visible cut edge)

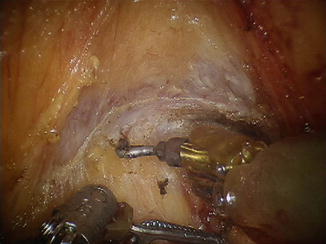

During anterior rectal mobilization, the dissection can be carried out on either side of Denonvilliers’ fascia as indicated by the tumor. It is important to note, however, that in men, this exposes the fine neurovascular plexus of the seminal vesicles and prostate, while in women, it exposes the sinusoidal vessels of the vaginal wall. In addition, seminal vesicles and associated neurovascular structures can be exposed and at risk for injury (Fig. 1.11).

Fig. 1.11

Denonvilliers’ fascia cut and deflected posteriorly, exposing the seminal vesicles

Waldeyer’s Fascia

There is some controversy with regard to Waldeyer’s fascia in rectal anatomy texts [14–17]. While this fascia, also known as rectosacral fascia, has been an anatomical and cadaveric observation, it has limited impact on rectal cancer surgery, as long as the principles of total mesorectal excisions are followed. Many textbooks depict Waldeyer’s fascia as an anteroinferior extension of the presacral fascia, separated from the latter at the S4 level and running toward the rectal tube [14, 15, 17]. Others have depicted it as a layer penetrating the mesorectum [16, 18] or a layer running closer to the levator muscles that requires sharp division in order to provide full posterior rectal mobilization [15].

Parietal Fascia (Fascia of the Lateral Compartment)

The parietal fascia (PF) separates the mesorectal compartment from the lateral pelvic compartment and transitions into Denonvilliers’ fascia anteriorly. The PF is closely related to the hypogastric nerve and the pelvic plexus, putting these structures at risk during dissection. At the mid-rectal level, it can also be adhered to the mesorectal fascia, a result of small nerve endings (nervi recti) entering the mesorectum from the pelvic plexus. When medial retraction is applied to the mesorectum, a tethering can be observed [19] (Figs. 1.12 and 1.13). This has been described in the literature as the “lateral ligament” [20]. We prefer the term “lateral tethered surface” (LTS) . The tethering is caused by the small nerve structures, fatty and connective tissue, and small blood vessels crossing from the lateral to mesorectal compartment [21].

Fig. 1.12

Parietal fascia of the mesorectal compartment (blue) originating from the endopelvic presacral fascia separates the mesorectal compartment (MC) from the lateral compartments (L) and transitions into Denonvilliers’ fascia (DF) in the region of the lateral tethered surface (LTS)

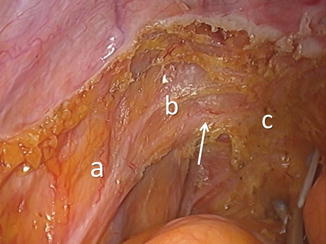

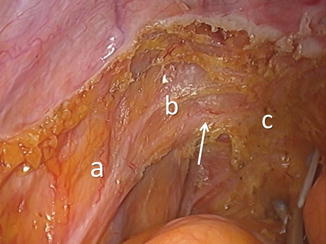

Fig. 1.13

Lateral tethered surface (LTS) on the left side, the point of insertion (arrow) of nerve fibers from the pelvic plexus (b) to the mesorectum (c); left hypogastric nerve (a)

Peritoneal Coverage

The upper portion of the rectum is invested by peritoneum anteriorly and laterally, while the middle part only anteriorly. Finally, the lower rectum is completely extraperitoneal below the peritoneal reflection. Thus, in an average-sized individual, the peritoneal reflection corresponds to the level of the second valve of Houston. This translates to the level at about 6–8 cm from the anal verge in women and 7–10 cm in men. Patient habitus such as height, obesity, and pelvic musculature can affect these distances.

Anatomical Relations

The anatomic relations of the rectum should be carefully considered during surgical resection, particularly with locally advanced tumors which extend beyond the mesorectal fascial plane . Posteriorly, these structures include the sacrum, coccyx, piriformis, and levator ani muscles, as well as the sacral nerve roots. Anteriorly, the bladder or uterus and vagina in women and seminal vesicles, neurovascular bundles, and the prostate or urethra in men may be at risk. Potentially involved lateral structures may include the hypogastric nerve trunks, the ureter, or the lateral structures such as the internal iliac vessels or associated nodal compartments.

Anus

The anus is the terminal portion of the alimentary tract. It consists of the anal canal and the anal margin. In the clinical sense (surgical and also functional), the anal canal extends from the anorectal junction, at the superior border of the levator hiatus, to the anal verge (Fig. 1.3). The anal verge is the point of contact of the examiner’s thumb made to the anoderm during digital rectal exam using the index finger. The average length of the anal canal in women is 2.5–3.5 cm, and in men it is 3–4 cm. This length is dependent on the muscle tension and is shorter under general anesthesia and deep sedation.

The anal margin is a circular, doughnut-shaped area located outside the anal verge within a 3–3.5 cm radius. The anal canal is a functional unit created by the sphincter muscle complex which can dilate to accommodate stool evacuation. It is located anteriorly and inferiorly from the coccyx, anterior to the deep postanal space and next to the ischioanal space. In women, it is posterior to the distal vagina, while in men it is posterior to the membranous portion of the urethra, the origin of bulbospongiosus (often described as bulbocavernosus) muscles, and Cooper’s glands.

Sphincter Complex

The sphincter muscle complex is comprised of two muscular tubes (Fig. 1.2). The external tube (external sphincter) is longer and thicker and derived from striated (skeletal) muscle. The internal tube (internal sphincter) is significantly thinner and slightly shorter and comprised of smooth muscle. The difference in length between the two sphincter tubes creates the intersphincteric groove which is an easily palpated important landmark.

The external anal sphincter is a 3–4 cm long elliptically shaped structure. It works as one functional unit comprised of four subunits, including the most cephalad puborectalis sling and three ring-like layers: deep, superficial, and subcutaneous [22]. The puborectalis muscle is a U-shaped muscular band originating from the pubis and linking the levators plate to the rest of the external sphincter. This muscle is responsible for creation of the anorectal angle and, in large measure, for overall fecal continence. The external sphincter complex, through its superficial unit, is fixed to the coccyx by the anococcygeal ligament located below the levators plate . It is also fixed anteriorly to the perineal body where it merges with the transverse perineal muscles.

The internal sphincter muscle is a 2.5–3.5 cm long tubular structure located inside the longer tube of the external sphincter muscle. It is made by concentric smooth muscles lamellae. Overall, the thickness of the internal sphincter tube is approximately 2–4 mm. At the anorectal junction, the internal sphincter transitions into the inner circular muscle layer of the rectal wall. An outer longitudinal layer of the rectal wall, together with some fibers of the levator muscles, creates a very thin muscular layer called the conjoined longitudinal muscle (CLM) [23]. The CLM runs within the intersphincteric space thus separating both the internal and external sphincter tubes. This observation is strictly anatomical and does not have any specific clinical implications for rectal cancer surgery. However, for the surgeon performing intersphincteric dissection, it is more practical to associate the conjoined longitudinal muscle with the internal sphincter. The intersphincteric space is a potential space of surgical dissection and does not contain any relevant vasculature (Fig. 1.14).

Fig. 1.14

Avascular intersphincteric plane ; longitudinal conjoined tendon covering the internal sphincter; view from the pelvic side (courtesy of Prof. Amjad Parvaiz)

Lining of the Anal Canal

The anal canal lining consists of rectal-type mucosa in the upper half and cutaneous coverage in the lower half. The demarcation line between these embryologically different types of epithelium is called the dentate line (pectinate line) , a sawtooth line located in the middle of the anal canal. Above the dentate line, an interposed transitional zone exists (6–12 mm segment) containing the columnar, transitional, and squamous epithelia [24]. The upper half of the anal canal contains 6–12 longitudinal mucosal folds (columns of Morgagni), which also extend below the dentate line as the anodermal folds. These folds are the result of the constricting effect of the sphincter complex on the lining of the anal canal. The columns of Morgagni are connected at their bases by the anal valves covering the outlets of the anal crypts.

The lining of the upper half of the anal canal is purple due to abundant underlying internal hemorrhoidal plexus. The lining of the lower half of the anal canal, called the anoderm , is pale pink, smooth and shiny, and devoid of true skin structures like hair, sweat, or sebaceous glands. At the level of the anal verge, the skin acquires pigmentation and hair follicles, as well as typical dermal structures, including the apocrine glands. Proximal to the dentate line, the bowel is derived from the endoderm and is supplied by the autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) nerves, while distal to the dentate line, the epithelium has somatic innervation.

Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor, also known as the pelvic diaphragm , is a sheet-like muscular structure created by a complex of muscle units. The purpose of the pelvic floor is to support the pelvic viscera and allow for secure passage for the alimentary and genitourinary tracts. While the levator ani muscle complex makes up the main “bulk” of the pelvic floor, complete coverage of the pelvic outlet involves three additional areas. The symmetrical greater sciatic foramina in the posterolateral pelvis are covered by two piriformis muscles. The midline defect in the anterior pelvis is covered by the deep transverse perineal muscle supported by a thickened portion of the endopelvic fascia on its cephalad surface called the urogenital membrane (also known as hiatal ligament ) (Fig. 1.15).

Fig. 1.15

Muscles of the pelvic floor

Internal Obturator Muscle

Proper understanding of the levator ani muscles involves discussion about the internal obturator muscle. The lateral attachments of the levator ani muscles are directly associated with this structure. The internal obturator muscle is attached to the inner surface of the superior and inferior ileo-pubic rami as well as to the obturator membrane spread over the obturator foramen (Figs. 1.15 and 1.16). From here, the muscle runs in the posterior direction, lining the entire lateral portion of the true pelvis and exiting it via the lesser obturator foramen (Fig. 1.17). The fascial coverage of this muscle creates an insertion place for the levator ani muscles (tendinous arch) . The tendinous arch runs dorsally as a straight line from the pubic symphysis, parallel to the superior ileo-pubic ramus, reaching the ischial spine. The insertion of the levator ani muscles, together with the lower aspect of the internal obturator muscle, can be appreciated from underneath the pelvic floor during the perineal phase of the abdominoperineal resection. It is also an important landmark during wide transection of the levators. In fact, in individuals with well-developed pelvic musculature, the bulky internal obturator muscle may be one of the structures narrowing the pelvic space, thereby adding difficulty during pelvic dissection (Fig. 1.17).

Fig. 1.16

Relation of pelvic arteries to pelvic floor muscles and the sacral plexus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree