Abstract

Quality measurement is necessary to identify gaps in health care quality and to assess the effectiveness of quality improvement initiatives. Multiple reports measuring the quality of breast cancer care provide evidence that inequities and disparities exist. In some cases, variation in care is associated with geography, institution, and surgeon, as well as patient race, socioeconomic status, and insurance status. To search for and address these quality concerns, multiple professional organizations have developed both quality measures and an electronic platform to capture quality data regarding the provider-patient encounter. Armed with this information, peer performance comparisons between providers—benchmarking—can improve quality. This chapter serves as a primer to present the best strategies for quality measurement and performance improvement for breast surgeons.

Keywords

quality, value, quality measures, quality improvement, quality gaps, benchmark, clinical outcomes research, peer performance comparison, patient registries, disparities, inequities, variability of care, safety, diagnostic errors

To say that the first 15 years of the 21st century has seen more emphasis on quality and performance measurement of hospitals and doctors than was seen in the entire 20th century is no exaggeration. Furthermore, payers of care, including the US government, have proposed shifting American medical reimbursement policy to payments that are tied to quality and performance instead of the number of services provided or procedures performed. The Department of Health and Human Service’s current target is that 50% of Medicare payments should be tied to quality or value through alternative payment models by 2018. Furthermore, public transparency of performance and what providers of care will be held accountable for will dramatically increase in the coming years. Change is occurring so rapidly that the benefits and risks they pose to patients and providers are not entirely known. Because these shifts are so consequential—and likely irrevocable—it behooves us to understand the opportunities and pitfalls that we face in advance. In this rapidly evolving framework of health care measurement, surgeons and other providers of care must ask themselves whether they are willing to be the stewards of it all. This chapter is a primer for breast surgeons interested in performance measurement and improvement.

Why Measure Quality?

The quality of health care received, including breast cancer care, varies by geography, institution, patient characteristics, and care provider. These variations account for the known disparities and inequities in care. Access to care and quality of care sometimes differ by socioeconomic status, education level, insurance status, and race. Documented quality concerns also include variations in appropriateness of care, with under- and overutilization of services resulting in differences in cost without adding value. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) provides notable examples of quality of care gaps in its seminal publications To Err Is Human: Crossing the Quality Chasm and Delivering High Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Such gaps exist along the entire continuum of cancer care, from diagnostic evaluation to survivorship, and include safety issues, unacceptable variability of care, and examples of failure to adopt evidence-based cancer care. Examples of these gaps include unnecessary diagnostic surgical excisional biopsies instead of needle biopsies and disproportionate numbers of patients undergoing breast-conserving therapy without receiving breast irradiation based on economic and insurance status. Some variability is evident even within institutions participating in national clinical trials.

There are other reasons to measure quality. Health care spending in the United States is currently rising faster than anywhere else in the world. This spending is not sustainable, nor is it associated with better outcomes. The Commonwealth Fund concludes that when based on cost and outcomes, the United States’ overall health care ranking is lower than that of nearly all of the countries of western Europe, New Zealand, and Australia. In a cross-national comparison of health care spending per capita in 11 high-income countries, spending in the United States far exceeded that of the other countries, largely driven by greater use of expensive technologies and notably higher prices. Despite this heavy investment, the United States ranked lower in many measures of population health, such as life expectancy and the prevalence of chronic conditions. An inverse association usually exists between quality and cost of care, so better quality care would be expected to lower costs, which would help to address our health care fiscal crisis. Increased cost of care is often associated with overutilization or waste of care. These and other observations motivated multiple professional organizations including the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBrS) to participate in the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely campaign, a national effort aimed at promoting appropriate care and reducing wasteful care. For example, routine systemic imaging to search for metastatic breast cancer preoperatively, then later during patient follow-up after initial treatment of early-stage breast cancer, is noncompliant with evidence-based guidelines and does not improve patient survival; rather, it increases care costs and leads to unnecessary additional testing and biopsies for false-positive findings.

Lastly, simply developing valid approaches to measure and report quality can have an important impact. Many studies have provided proof of concept that measuring breast cancer care quality and providing peer performance comparison usually correlate with improved care.

Who Are the Stakeholders for Quality Measurement?

The stakeholders interested in health care quality include patients and their providers of care, but they also include purchasers, payers, professional organizations, policy makers, patient advocacy groups, and the government. Although all stakeholders desire high-quality care, their perspectives and goals may differ. A historical example of differing stakeholder opinions occurred more than a decade ago when breast cancer patients were offered, then wanted, reconstruction after mastectomy but could not afford it because it was not covered by their insurance plan. From the payer’s perspective, reconstruction was costly and characterized as an optional “cosmetic” operation. In contrast, from the provider and patient perspective, reconstruction was of benefit—an attempt to restore normality, both physically and emotionally, after cancer surgery. Resolution of these conflicting arguments did not occur until after federal legislation, the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act of 1998, mandated reimbursement. This regulatory action resulted from a collaboration between stakeholders that including policy makers.

What Is the American History of Surgical Quality Measurement?

Ernest Codman at Massachusetts General Hospital was one of the first US surgeons to advocate for measurement of surgical outcomes, believing they provided the foundation for improvement. Dr. Codman reported the end results of 337 surgical patients treated from 1911 to 1916. He concluded there were 123 errors and 4 “calamities.” He advocated for surgeon accountability and transparency, and he recommended development of national patient registries. These were prescient concepts and remain relevant today. Unfortunately most of Dr. Codman’s peers disagreed with him. Thus, as a result of his quality advocacy, he was the victim of professional rebukes and social ostracism. There were likely many other surgical leaders interested in quality and outcomes research after the era of Ernest Codman, but few seminal conceptual articles were published on quality measurement during the next half of the century, perhaps reflecting Codman’s experience.

In the 1960s, Avedis Donabedian, a health care researcher at the University of Michigan, began refining the concepts of quality measurement, moving away from an unstructured peer-review method, such as traditional morbidity and mortality conferences, toward an objective “outcome-driven process.” He created a taxonomy of quality measurement based on structure, process, and outcomes of care—later called the Donabedian Trilogy— which is still in use today. Since the late 1990s, additional domains of quality to audit have been recommended. These include patient access, patient experience, affordability, population health, safety, effectiveness, and efficiency.

Moving beyond concepts and motivated by recognition of disparate care in the Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals, the development of methods to provide hospital-level peer performance comparison for surgical outcomes was accomplished in 1991. Beginning in 1994, Shukri Khuri and others described the system of auditing, peer comparison, and risk-adjusted analytics used by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to report surgical outcomes. They provided hospitals with report cards of postoperative morbidity and mortality. In 2004 the VA hospital program evolved into the ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP). Other notable surgeon champions of breast cancer quality improvement in recent years include David Winchester, Stephen Edge, Eric Whitacre, and Cary Kaufman. All provided pioneering work in the development of breast quality measurement by programs such as the Commission on Cancer (CoC), the National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers (NAPBC), the ASBrS Mastery of Breast Surgery Program, and the National Consortium of Breast Centers (NCBC). These programs have been recently summarized. The contemporary strategies to improve patient quality that are endorsed by multiple organizations are listed in Table 35.1 .

| Organization | Objective Name | Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Institute of Medicine a | Six Aims |

|

| Institute for Healthcare Improvement b | Triple Aim |

|

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Quality Strategy c | Three Aims |

|

| Six Priorities |

| |

| Nine Levers |

|

a Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century . Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

b The IHI Triple Aim. Institute for Healthcare Improvement < http://www.ihi.org/engage/initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx >.

c The National Quality Strategy. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality < http://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality >.

What Are Quality and Value?

Many organizations have defined quality (see Table 35.1 ). The IOM defines health care quality as an iterative process with six aims: safety, effectiveness, timeliness, efficiency, equitability, and patient centeredness.

Value of care has a broader meaning than quality of care. In addition to quality, cost is considered. Spending on breast cancer care is substantial—not surprising because it is the most commonly diagnosed non–skin cancer in women. Breast cancer expenditures account for the largest share of cancer-related spending. In 2006 Porter and coworkers defined a value metric as “patient health outcomes achieved per health care dollars spent.” Others describe it as the simple ratio of quality to cost of care. In his monograph Discovering the Soul of Service, Leonard Berry takes a patient-centered approach, defining the value of care as the ratio of quality to burdens, in which burdens can be both financial and human. Using a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database, Hassett and colleagues recently explored the relationship between breast cancer care, cost, and outcomes—as measured by adherence to recommended treatments and survival—in 99 geographic regions. Convincingly, they identified significant variability in all. They failed to identify an association between survival and cost of care. Process measures that assessed necessary and unnecessary therapies did not correlate with survival and they found evidence of expenditures for treatments not recommended. Other investigations have also provided evidence of unnecessary expenditures that did not aid survival, suggesting overutilization of some services with no gain. As the United States moves away from a system of fee-for-service and toward value-based reimbursement, many definitions of value are already in use or anticipated. Nearly all have or will have a quality metric in the numerator and a cost metric in the denominator, resulting in the creation of a value metric.

What Are Safety in Surgery and Diagnostic Errors?

Diagnostic errors and patient safety are commonly included under the rubric of quality. Surgical safety is of great importance for all surgical subspecialties, and safe surgery is necessary for good breast cancer surgical outcomes. Surgical safety checklists and safety improvement methodology have been nicely reviewed elsewhere. Direct observation of care may identify root causes of safety issues.

Diagnostic errors in medicine are common but underreported, according to a recent comprehensive review. The IOM’s updated 2015 definition of diagnostic error is “the failure to (a) establish an accurate and timely explanation of the patient’s health problem(s) or (b) communicate that explanation to the patient.” This definition frames this quality issue from the patient’s perspective, recognizing that errors may harm the patient, then parses it; accuracy, timeliness, and communication can all be measured, then segregated for audits and tracking. Diagnostic errors have been described as “missed opportunities,” either errors of omission (failure to order tests or procedures) or commission (ordering unnecessary tests, such as overutilization of systemic imaging in early-stage breast cancer patients). Relevant examples of diagnostic errors of omission in breast cancer care include delayed diagnoses attributable to misses on screening mammography and failure to recognize imaging-pathology discordance of breast lesions after image-guided needle biopsy that showed benign, indeterminate, or high-risk findings. Multiple reviews and publications have highlighted the reasons for a delayed diagnosis of breast cancer.

How Do We Identify a Gap in the Quality of Care?

The World Health Organization identifies gaps in health care quality by recognition of variability of care. Gaps are identified when measurements of actual care do not match achievable care and when variability of performance coexists with evidence that high levels of performance are obtainable. For breast care, searches for variability can be conducted in national databases such as the SEER and the National Cancer Database (NCDB). For example, interrogation of the NCDB and the American Society of Breast Surgeons databases recently identified wide variability of reexcision rates after breast-conserving surgery for cancer, indicating a performance gap. Searching for variability has been the primary method for identification of disparities and inequities of care based on socioeconomic status, race, location of care, and other demographic characteristics.

Where Are the Databases for Quality and Clinical Outcomes Research?

Institutions throughout the United States are generating an ever-increasing amount of electronic data. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 included $17 billion in Medicare/Medicaid incentive payments for the adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) starting in 2011, and reductions in Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement for nonadopters beginning in 2015. In addition to the obvious economic implications, this mandate represents an enormous opportunity to evaluate quality and clinical outcomes. The ability to access and analyze these data will markedly improve our ability to study practice patterns, compare the effectiveness of treatment beyond clinical trials, evaluate performance, and provide objective feedback to practitioners. Although significant progress is being made, we currently still rely primarily on the secondary use of administrative data and manual abstraction from cancer registries.

The secondary use of administrative data, the most common data source for such activities, is limited for breast cancer care by the need for accurate pathologic data, such as stage and histology. The abstraction of administrative data from hospital systems (e.g., discharge data) can be available from a variety of sources, such as state hospital associations or private consortiums, such as the University HealthSystem Consortium. Other administrative data exist in the form of insurance claims. Such data are more flexible than discharge data but can be cumbersome to analyze and often represent a biased sample of the population. For example, Medicare claims are often used to evaluate quality and outcomes, but Medicare data come only from patients aged 65 years and older. Thus their utility is limited for cancers that primarily occur in young patients (e.g., testicular cancer) because the biology and treatment of the disease in elderly patients are different from those in younger patients (e.g., breast cancer). Furthermore, claims data cannot be linked to the medical record for more specific information as advances are made (e.g., genomic profiling). These data are, however, extremely well suited to surgical questions. Because they are tied directly to payment, surgical and other procedure codes are reliable and represent a clear, distinct intervention.

Clinical cancer registries exist at the institutional, state, and national levels. State cancer registries vary greatly in terms of the completeness of data. The most common national cancer registries are the SEER and the NCDB of the CoC. The NCDB abstracts data from the more than 1200 CoC-accredited institutions, representing more than 70% of the newly diagnosed cancers in the United States. It is an extremely powerful tool for investigating quality and outcomes that are directly tied to clinical care; however, limitations in the capture of treatment information can limit its application for such measures. It is also important to recognize that the NCDB is not a population-based data set. SEER, on the other hand, now collects data from 18 sites around the United States that were selected to ensure representation of socioeconomic and racial diversity. Because it includes all individuals living in the site, this is a population-based data source, which can be important for generalizability. Another major and well-recognized limitation of cancer registries is the inability to accurately track recurrence. As patients move from one geographic region to another, and even between hospitals within a region, longitudinal outcomes can be difficult to track, and capture of recurrence, in particular, is noted to be unreliable.

Such registries can provide accurate pathologic and other cancer-specific information, but often have less accurate information on treatment, and little to no information on comorbidity. In addition, data elements in cancer registries are manually collected and entered, making it extremely resource-intensive to collect and maintain, resulting in a considerable lag time before data are available for analysis. A number of initiatives have linked cancer-specific variables from registry data to the details of treatment available in administrative data in order to take advantage of both sources. The best example is SEER-Medicare, which links cancer registry data from SEER with Medicare claims data.

Many of the data elements that are lacking in traditional administrative data sources, including cancer-specific variables, are available as unstructured free text in EHRs. To access these data in a cost-efficient manner, automated approaches can be used to extract key measures pertaining to patient, disease, and treatment characteristics. To date, a number of EHR-based initiatives abstract data from multiple institutions and systems to create a virtual data warehouse. Perhaps the most relevant for the quality and outcomes of breast cancer patients is the National Cancer Institute–funded Cancer Research Network, which draws from multiple health maintenance organizations. With the continued expansion of EHRs, a number of new national initiatives aim to increase the availability of these data for the evaluation of clinical effectiveness, quality, and outcomes. The National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network, a major initiative of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, funds the creation of multiple large data warehouses with standardized data structure.

How Do We Measure Quality?

Physician competency may be assessed using a number of methods. Hospitals require credentialing, states require licensing, and the American Board of Surgery requires certification. These are mandatory basic levels of surgeon competency. They do not necessarily measure surgeon technical proficiency. The shared goal of these activities is the desire to increase the likelihood that quality care will be provided during a surgeon-patient encounter. After these administrative and regulatory entry thresholds have been achieved, recertification, credentialing, and licensing are most often based on annual Continuing Medical Education credits, essential for maintenance of board certification. Occasionally, peer review by a Department Chair is necessary for renewal of hospital privileges. More recently, direct measurement of postoperative outcomes has been used for some credentialing decisions and by some payers of care for patient steerage decisions. Increasingly, the most common method of assessing care provider performance has been quality measurement and peer comparison. These methods provide a potential framework for departure from fee-for-service systems of reimbursement to incentivized pay-for-performance systems.

Quality of care is measured by auditing outcomes. From existing patient registries, there is a vast body of information on general and breast surgeon outcomes, especially postoperative morbidity and mortality. Complications are costly and delay patient recovery. However, because the likelihood of death or major morbidity after breast operations is so low compared with more complex general surgical operations, it is of limited use for quality improvement in breast care. As a result, breast-focused organizations have endorsed other measures of quality. A common method of measuring breast surgeon quality is to measure their compliance rate with an evidence-based process of care. This seemingly simple evaluation of provider quality has recently been scrutinized. Although guideline compliance is intuitively the best care, a few studies dispute the notion that higher measured compliance rates always identify better surgeon quality and reliably improve patient outcomes. The hypothesis that maximization of guideline adherence is best care may be too simplistic because there can be valid reasons for noncompliance with guidelines, such as patient preferences, limited life expectancy, and comorbidities. Using the patient registry for certified breast centers in Germany, Jacke and colleagues reported on 104 quality indicators that were based on guidelines, categorizing the care decisions of each study patient as either adherent or divergent. Overall guideline adherence increased and divergence decreased over 8 years, resulting in a twofold increase in quality as measured by the process of care. However, a systematic effect of adherence linked to overall survival was not evident, reflecting what the authors termed an “adherence paradox” because increased guideline compliance was not associated with a better outcome.

Procedural volume as a surrogate measure of quality is controversial. The controversy stems not only from the use of volume as a measure of competency per se but, rather, its potential use for distribution of care. This use of volume as an accountability measure restricting a surgeon’s eligibility to care for a patient needing a specific operation has been proposed and endorsed by some hospital systems. For now, the proponents of using volume for case distribution are focusing on complex gastrointestinal procedures, such as hepatic, pancreatic, and bariatric surgery. Although not yet used for patient steerage in breast care, a direct volume-outcome relationship has been reported. The primary argument for using volume as a measure of quality is that some studies indicate a significant association between higher volume and better outcomes. However, surgeons with lower case volume have demonstrated outcomes comparable to those of high-volume centers. Furthermore, patients often prefer care that is closer to home and to their social support system.

Quality of care can also be measured from the patient’s perspective by patient survey. These are termed patient-reported outcomes (PROs). They are also called patient-centered and patient experience quality measures. Multiple patient surveys are available, including those specific to both general or breast surgeons. The surgical care questions embedded in these surveys assess the domains of access, timeliness, and pain control, as well as functional, psychological, sexual, and cosmetic outcomes.

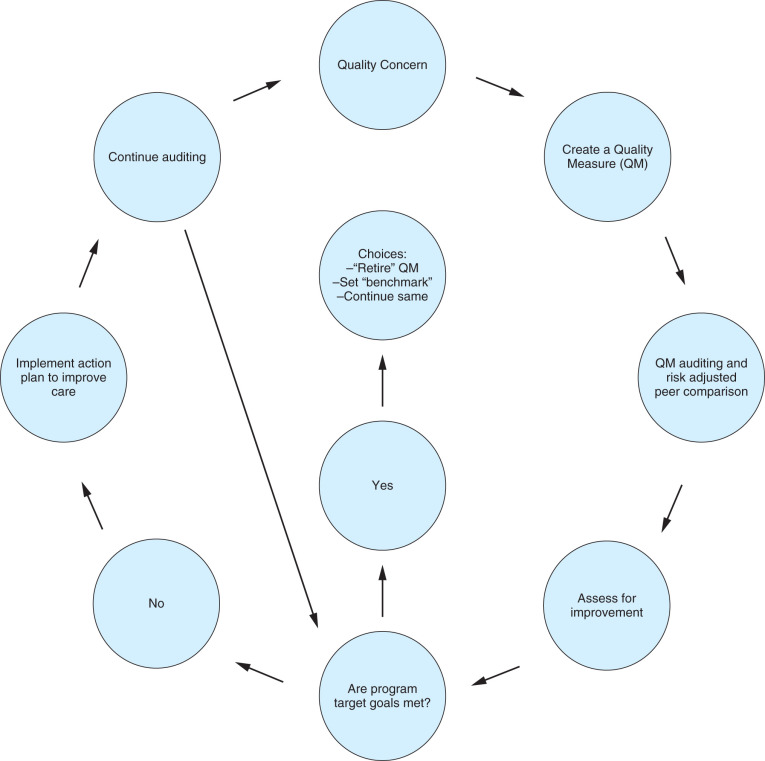

What Is a Quality Measure, and Where Do We Find Them?

A quality measure (QM) is a fraction that attempts to quantify quality in a domain of care. A QM has a specific numerator, denominator, and inclusion and exclusion criteria. Collectively, these are the specifications of a QM. There are multiple measure types, reflecting measurement in different domains of care. Measure types include the Donabedian trilogy of structure, process of care, and outcomes. Newer domains of care for QM development include access, timeliness, patient-centeredness, affordability, efficiency (appropriateness), efficacy (evidence-based), care coordination, cost/resource, and population health.

Structure or setting of care reflects the environment in which a care provider practices. For example, a geographic and scheduling model that provides patient navigation and care coordination with all specialty care providers meeting with the newly diagnosed patient at the same time and place would be a structure expected to engender care coordination and high-quality patient-centered care. Another important structural measure that is being developed is the requirement for a survivorship care plan at the completion of treatment. For a breast surgical encounter, examples of operative structure that foster better care are the availability of intraoperative specimen imaging with immediate radiologic interpretation and immediate access to histologic assessment in the operating room during breast-conserving surgery for nonpalpable breast cancers. The measurement of a structural QM is usually dichotomous: it is either present or absent. For example, the structural presence of a tumor board is necessary for NAPBC accreditation.

Process of care measurements usually involve auditing compliance with evidence-based treatments, such as National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)-recommended care for management of the axilla or adjuvant chemotherapy, endocrine, or radiation treatments within a designated timeframe. For process measures, the difficulty often lies in determining the appropriate denominator based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. For example, the recommendations for chemotherapy include age, histology, receptor status, and tumor size. As previously discussed, such specific characteristics can be challenging to obtain from existing data sources.

An outcome QM determines the actual results of care. Key outcomes of cancer treatment—overall survival, disease-free survival, and local regional recurrence—are important to measure but have limited use as a single-surgeon QM due to the attribution issues, as well as to the long length of follow-up required. Cancer recurrence depends on the actions and recommendations of multiple nonsurgeon providers, patient choice, and adherence to treatment, none of which are completely controlled by the surgeon. Other limitations in the use of outcome measures include low case volume and event rates for many breast surgical procedures, limiting the ability to provide stable estimates.

The most common general surgery outcome measures focus on postoperative complications after surgery, such as venous thromboembolism, bleeding, sepsis, organ failure, and surgical site infection. They are limited in their relevance for breast surgeons because they are such infrequent events. As a result, efforts to develop more meaningful breast surgeon–specific QMs have occurred ( Table 35.2 ). Surgeon- and breast center–specific QMs are listed in Table 35.3 .

| Organization | Breast Center | Breast Surgeon | Breast Oncologist | Hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Society of Breast Surgeons a | ✘ | |||

| American Society of Clinical Oncologists | ✘ | |||

| National Consortium for Breast Centers | ✘ | ✘ | ||

| National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers | ✘ | |||

| Commission on Cancer | ✘ | |||

| National Surgical Quality Improvement Program b | ✘ | ✘ |

a Only program that allows breast surgeon participation in Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services incentivized payment programs.

b The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program includes measures of breast morbidity and mortality outcomes in its general surgeon reporting.

| PQRS Measures | |

|---|---|

| American Society of Breast Surgeons |

|

| National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers and the Commission on Cancer |

|

| National Consortium for Breast Centers |

|

| ASCO Quality Oncology Practice Initiative Measures | N = 62 breast measures b |

a The quality measures listed are simplified descriptions. Full specifications of the measure are accessible through the organizations’ websites.

b Available at http://www.asco.org/quality-guidelines/summary-current-qopi-measures .

Recent advances in QMs include the development of cross-cutting and composite QMs. Cross-cutting is a term describing a single QM expected to be relevant to multiple specialties. Examples include medication reconciliation post discharge, functional outcome assessment, pain assessment and follow-up, and care plan. Providing a cancer patient with a portable (whether paper or electronic) staging and survivorship document, and updating that document as the patient’s circumstances change, is an example of a cross-cutting QM. In this example, the document is iterative, changing over time from diagnosis through treatment, but it remains relevant forever to aid care coordination and communication.

A composite measure summarizes a group of QMs that are related in some way, such as multiple processes of care related to a specific disease condition or to an episode of patient care. In describing one type of use of a composite QM, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) suggests the measure denominator be the sum of processes that constitute a panel of appropriate process measures. With this example, the numerator is the sum of the processes of appropriate care that are actually delivered. Surveys describing PROs in multiple domains of care can also be reported as a single composite number. The survey may calculate separate scores for as many as eight domains of mental and physical health after breast cancer surgery, and then combine all to create a single composite score of 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better health quality. Composite measures can include a functionality allowing different statistical weighting for the individual measures used in the construct of the measure. Composite measures with weighting were better than using individual postoperative complication rates or hospital volume to explain hospital-level variations in quality after bariatric surgery.

The newest measure types under development by the National Quality Forum (NQF) are cost/resource measures. These measures are intended to determine risk-adjusted payments to providers for an episode of care. Initially, the NQF is developing these for medical conditions, such as acute myocardial infarction. Bundled payments for surgical episodes of care are being developed.

The programs and their quality measures available for reporting on the care of patients with breast cancer are listed in Tables 35.2 and 35.3 . They have been recently reviewed. Most programs provide peer comparison. In the CoC program, rapid feedback is provided on whether compliance with QMs, such as endocrine therapy for hormone receptor–positive breast cancer patients, was accomplished. This feedback exemplifies one of the first national efforts to link QM reporting to the notion that reporting can improve quality by using time-sensitive prompts. The ASBrS Mastery SM is the only program that provides surgeons with the opportunity to participate in Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)-incentivized payment and penalty programs with breast surgeon–specific measures ( Table 35.3 ). An example of the full specifications of one of these measures is provided in Fig. 35.1 .

What Are the Quality Reporting Systems in the Public Sector?

The interest in quality measures is complemented by the desire for payers and the public to collect metrics of quality and potentially distribute them. Because there is virtually an unlimited number of programs that occur across the private sector, we focus on the public sector in this chapter.

The Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 created the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative, which CMS implemented as the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). This provided for a bonus payment of as high as 1.5% for participation in data collection. The program was made permanent in 2008 and required that CMS post the names of eligible physicians and group practices, which can currently be found on the Medicare Physician Compare website. In 2010 the Affordable Care Act (ACA) required further changes, most importantly the implementation of a feedback mechanism and an appeals process. It also required the development of penalties that began in 2015. Penalties for nonparticipation in PQRS would be as high as 2% of payments, based on the reporting from 2 years prior (e.g., 2015 penalties would be based on 2013 participation).

In addition to those incentives and penalties, there are potential additional incentives and penalties based on the value modifier (VM), which is intended to measure resource use relative to quality. Based on 2014, providers will be tiered into low-, average-, and high-cost, as well as low-, average-, and high-quality tiers. Those that overperform (e.g., average or high quality for low cost, or high quality for average cost) will be rewarded with additional incentives. A 1% additional bonus is also available for those groups serving high-risk beneficiaries based on average risk scores. The VM dollars at risk will depend on eligible provider group size and year of reporting. In 2016 and 2017, it will range up to a 2% and 4% penalty, respectively, reflecting care in 2014 and 2015. The upper limit of incentivized reward has not been determined at the time of this writing.

The requirements for individual physicians to avoid the PQRS penalty for 2017 (to be performed in 2015) are as follows. Physicians may report data based on paper claims, directly via an EHR, via Registry, or via a Quality Clinical Data Registry (QCDR). Each has slightly different requirements; however, they generally must include reporting of at least nine measures across three or more National Quality Strategy Domains selected from the PQRS Measures list for that year, which in 2016 includes more than 250 measures. In addition, one of those measures must come from the cross-cutting measure list. Although the bulk of the measures apply most closely to primary care–oriented specialties, a number of them have been submitted by the ASBrS and were designed with breast surgeons in mind. Measures that are oncology- or specialist communication–focused may also be appropriate for breast surgeons. Breast surgeons wanting to report breast surgery–specific measures can find more information on the ASBrS website.

Group practices may choose to report together; however, to do so they should register for the Group Practice Reporting Option. Groups do not have a paper claims options, but groups larger than 25 qualify for a Web interface option. In addition, groups reporting together should also plan to work with a CMS-certified vendor to administer the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey. This is required for groups of more than 100 eligible professionals but can also be utilized for any group larger than two as an option.

Late in 2015, CMS released Quality and Resource Use Reports (QRURs) to all solo practitioners and group practices nationwide based on the 2014 data; however, these data will affect only groups with 10 or more eligible professionals. To avoid the penalty that is based on the VM, groups must have reported successfully on PQRS measures as well, or had at least one member participate in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. Details can be found on the CMS website for the precise calculation. Quality measures include those utilized through PQRS as well as hospital admissions or chronic conditions for acute diagnoses that may be avoidable and 30-day hospital readmissions. Cost measures are based on the Fee for Service Medicare claims that are attributed to the group. These are calculated both overall and on specific conditions as well. Providers are tiered into high-, average-, and low-cost, calculated based on the standard deviation of the cost scores.

There have been a number of criticisms of the current approach to quality reporting in programs described earlier. First and foremost, the incentive payments have been tied primarily to participation and not achievement of any specific targets. Most of the current measures are focused on the process of care, rather than risk-adjusted outcomes of care. In addition, payments have been an all-or-nothing approach, meaning that for providers who are unable to achieve the reporting threshold, no payments are given at all.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree