- The interactions between diabetes and psychiatric disorders are complex: physical illness raises the risk of psychiatric disorder, but mental illness and its treatment also impact on the risks and outcomes of diabetes.

- Because mental health problems are common among people with diabetes, good levels of awareness and knowledge are vital for the health professionals who work with them.

- A strong case has been made for implementation of screening for mental health problems in a range of care settings.

- Increased availability of mental health expertise in the settings where people with diabetes are treated is required.

Introduction

The interaction between mind and body is central to the management and outcome of all chronic diseases, but is perhaps particularly complex and fascinating in the case of diabetes. Diabetes is no longer an invariably fatal condition; however, in order to maintain good health, many patients face high behavioral demands. Psychiatric disorders may significantly compromise the ability of the patient to perform self-care to the required standard for optimum health, leading to increased risks of poor outcomes including complications and premature mortality.

Both diabetes and psychiatric disorders are common conditions, and therefore a degree of co-occurrence would be expected purely by chance; however, there is a considerable body of evidence that diabetes is associated more frequently than expected with a range of psychiatric morbidity. In particular, it appears that patients with mood and psychotic disorders are at increased risk of developing diabetes, and people with diabetes go on to develop a range of psychologic problems at increased rates compared to healthy controls. This was first noted over a century ago; as Henry Maudsley said in his celebrated textbook, Pathology of Mind, when discussing the increased rates of diabetes observed among psychiatric patients [1]:

“Diabetes is a disease which often shows itself in families in which insanity prevails. Whether one disease predisposes in any way to the other or not, or whether they are independent outcomes of a common neurosis, they are certainly found to run side by side, or alternately with one another more often than can be accounted for by accidental coincidence or sequence”.

Knowledge of the special problems that occur when diabetes and a psychiatric disorder coincide is essential if optimum care is to be provided. Unfortunately, in most countries, services are not well organized to deliver good quality care for both the physical and psychologic needs of patients in the same setting. Clinicians need to be aware of the increased risks of co-morbidity, and the need for screening. Diabetes health care professionals should be able to provide “first response” management, and recognize the needs of those more complex patients for whom specialist management is essential. The topic of co-morbidity is also attracting interest from researchers, and there is the potential for considerable progress in understanding the epidemiology and psychobiologic mechanisms involved. The increased availability of objective measures of glycemic control and diabetes outcomes over the past few decades has opened up the possibility of a wide range of psychobiologic research. This chapter provides an overview of the current state of knowledge of these topics, and highlights needs for further research.

Mood disorders

Until quite recently, any discussion of mood disorders and diabetes would have concentrated solely on the increased rates of depression observed in cohorts of patients with diabetes, and is likely to have viewed such co-morbidity mainly as an “understandable” reaction to the difficulties resulting from living with a demanding and life-limiting chronic physical illness. We now understand that the interaction between the two conditions is more complex than this:

- Depression may itself be a risk factor for the development of diabetes;

- Biologic aspects of diabetes may contribute to the development of depression;

- Other antecedent factors, such as the early nutritional environment, may have a “common soil effect,” thereby contributing to the risks of both conditions.

Depression can also impact on the clinical course of the diabetes, increasing the risk of poor glycemic control and complications. People with both diabetes and depression have been found to have higher symptom burden, poorer functional status, poorer self-care and higher health care costs [2].

Case definition

Depressive symptoms exist on a continuum of severity. Standard definitions of “clinical” depression are based on symptom count and duration; the most widely used diagnostic criteria in current practice are those of the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-IV “major” depression (Table 55.1) [3].

Table 55.1 DSM-IV “major” depressive episode.

| Five or more of the listed symptoms should be present nearly every day, for at least 2 weeks, and should represent a change from normal functioning; at least one of the first two symptoms in the list must be present Symptoms 1 Depressed mood for most of the day 2 Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities for most of the day 3 Significant weight loss when not dieting, or weight gain (change of 5%), or decrease or increase in appetite 4 Insomnia or hypersomnia 5 Psychomotor agitation or retardation 6 Fatigue or loss of energy 7 Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt 8 Diminished ability to think or concentrate 9 Recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation |

This definition is to some degree arbitrary; however, it approximates to a level of symptomatology that is associated with significant disability and dysfunction, and is very widely accepted as a standard in both clinical practice and research. It is important to note that depressive disorders of lesser severity may still compromise self-care and outcomes in people with diabetes.

The clinical category of mood disorders includes both unipolar depression and bipolar (“manic-depressive”) illness. This section focuses on unipolar depression; bipolar illness is included in the section on psychotic disorders.

Epidemiology

Unipolar depression is one of the most common mental health problems in the general population, affecting 3–5% of the population at any time, and its prevalence appears to be increasing, such that the World Health Organization have estimated that it will be the second leading cause of disability (after heart disease) in the world by 2020 [4].

There have been many studies of the prevalence of depressive symptoms and disorders in people with diabetes over the past 40 years. Most of the early studies, however, had significant methodologic shortcomings.

First, they lacked standardized definitions of depressive disorders, mainly using rating scales of unknown reliability and validity in a diabetic population. The “gold standard” for ascertainment of case status is a research diagnostic interview; most rating scales can only give a probabilistic estimate of caseness. In addition, there may be an overlap between symptoms of diabetes and those of depression (e.g. fatigue, weight loss).

Second, studies have tended to ignore the heterogeneity of people with diabetes, studying mixed populations of patients with different forms of diabetes (e.g. type 1 [T1DM] and type 2 [T2DM]). It is important to distinguish between these groups for several reasons:

- Although there is increasing overlap, people with T2DM are older and depression prevalence varies with age;

- There may be differences in pathologic mechanisms;

- The rates of diabetic complications and other co-morbid conditions (e.g. obesity, heart disease) differ; and

- The demands of management are different.

Third, studies have often been based on “convenience” samples of patients, usually drawn from diabetic clinics, where the operation of referral and other biases in sample composition was of unknown effect. Ethnicity is also an important confounder for rates of both depression and diabetes.

Finally, studies have had low or unknown response rates, and because the presence of depressive symptoms may reduce the likelihood of responding in such studies, this biases prevalence estimates further. Not surprisingly, as a result the range of prevalence figures that can be found in the literature is very wide.

More recent studies, using better methods, and meta-analyses, have led to lower estimates of prevalence. For example, one recent review of the prevalence of co-morbid depression in people with T1DM [5] concluded that clinical depression was present in 12%, compared with 3.2% in control subjects without diabetes. Caution is still needed in the interpretation of this finding, because it was based on only 14 studies, of which only four included control groups and only seven were based on interview methods. Excluding studies without control groups and interview ascertainment led to a fall in estimated prevalence to 7.8%, a figure that, although still raised, is no longer statistically significantly different from that found in healthy controls (odds ratio [OR] 2.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] –0.7 to 5.4).

Studies of depression in people with T2DM tend to be based on larger samples, given that around 85% of patients have this disease subtype. A recent study based on clinical diagnoses from a US Health Maintenance Organization [6] concluded that depression was more common in people with T2DM (17.9%) than in matched controls (11.2%), with marked sex differences: depression was nearly twice as common in women, but the effect of the presence of diabetes was greater in men. The effect remained after adjustment for covariates such as cardiovascular disease and obesity.

Depressive disorders as a risk factor for diabetes

The suggestion that emotional factors, such as grief or sadness, could lead to the onset of diabetes was first raised by Thomas Willis in 1684. It is a common clinical observation that the onset of diabetes may follow a depressive episode, although because T2DM often goes undiagnosed for years, the apparent association may be at least partly the result of ascertainment bias – patients with depression are more likely to have a screening test for diabetes than those without.

A recent systematic review has addressed the question of the direction of the association between these conditions, and summarized the evidence that depression may be a risk factor for diabetes [7]. Unfortunately, the vast majority of existing studies are cross-sectional and therefore uninformative about this issue. The reviewers were able to identify nine longitudinal studies, and the analysis suggested that depressed adults have an increased risk of developing T2DM of around 37%; however, this must be regarded as a preliminary finding, and further large well-designed longitudinal studies are needed.

Proposed mechanisms linking depression and diabetes

Psychosocial factors

Most studies confirm that risk factors for depression in otherwise healthy individuals operate equally in people with diabetes. Thus, socioeconomic hardship, poor education, stressful life events and lack of social support are all important [8]. Gender differences are also important. There is relatively little evidence that people with diabetes differ greatly with respect to these types of risk factors, and it can be concluded that much depression in people with diabetes may be “independent” of the presence of the disease, an issue that may be particularly important when it comes to management planning.

Early nutrition

One putative common risk factor that may increase the risks of both of diabetes and depression is that of disrupted nutrition during fetal life. There are now over 38 reports linking poor fetal growth with impaired glucose metabolism in later life [9]. Most of these studies report an inverse relationship or J-shaped relationship between birth weight and plasma glucose and insulin concentrations, the prevalence of T2DM and measures of insulin resistance and secretion. Similarly, the risk of depression has been found to be associated with low birth weight for both young and older adults [10]. Furthermore, data from the Dutch Hunger Winter study showed that exposure to famine during the second or third trimester of fetal life is associated with increased risk of hospital treatment for major affective disorder [11].

The mechanism underlying this association is not clear but one hypothesis proposes that fetal programming of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis may play a part.

Shared genetic risk

Another suggested mechanism that may link diabetes and psychiatric disorder is that of shared genetic variance. There is some evidence that close relatives of people with some forms of psychiatric disorder have an increased incidence of diabetes [12], and known loci for the disorders occur in overlapping positions within chromosomes [13]. Investigation of this intriguing possibility is in its infancy and further research is needed.

Inflammatory mechanisms

It has been hypothesized that inflammation and increased production of proinflammatory cytokines by activated immune cells may mediate the association between depression and diabetes, with associated perturbation of the HPA axis [14]. Parallels have been noted between depression and so-called “sickness behavior” seen in response to the elevation of cytokines, interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). It is thought that such cytokines may be released in increased amounts from adipose tissue in conditions including diabetes and obesity as people age, and this may interfere with insulin action.

Counter-regulatory hormones

Acute psychologic stress is known to increase circulating concentrations of counter-regulatory hormones including noradrenaline, glucocorticoids and growth hormone (GH), which antagonize the hypoglycemic action of insulin. Although the effects of chronic stress on the HPA axis are somewhat less well understood, the view of depression as a maladaptive prolonged stress reaction has some empirical support.

Loss of normal diurnal variation in cortisol levels together with non-suppression of cortisol release in response to exogenous steroid administration have long been noted as hallmarks of depressive illness, particularly the “melancholic” subtype. It is suggested that this may lead to increased glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, lipolysis and inhibition of peripheral glucose transport and utilization [15]. Non-diabetic patients with depression have been shown to have increased insulin resistance, but further investigation of this mechanism is warranted. Glucose transport in the brains of people with depression has also been shown to be abnormal [15].

Depression and glycemic control

Several studies have demonstrated an association between the severity of depressive symptoms and the level of glycemic control as assessed by glycosylated hemoglobin level (HbA1c) [16], although the size of this effect has been generally modest, and may be explained by confounders such as the presence of microvascular complications. Most studies have been cross-sectional in nature, although some treatment studies have suggested that improvements in glycemic control are associated with reduction of depressive symptoms.

Depression and complications

There seems to be little doubt that the risk of depression increases as microvascular and macrovascular complications accrue over the course of the disease [17]. The evidence is less strong that the presence of depression increases the risk of developing complications, although the fact that self-care and resulting glycemic control are impaired would lead to this expectation. One longitudinal cohort study of 66 people with T1DM found that depression was an independent risk factor for retinopathy at 10 years [18], but other studies have had negative results. The meta-analysis of de Groot et al. [17] supports a positive association.

One complication that may have a particular association with depression is that of peripheral neuropathic pain. Recent studies suggest that not only is chronic pain a risk factor for depression, but the presence of depression may itself worsen the experience of pain. Common neurotransmitters appear to be involved in both depression and pain [19].

Management of people with diabetes and depression

At present, advice for the management of patients with co-morbid depression and diabetes is based on evidence derived from populations without diabetes because the number of treatment studies in people with diabetes is as yet too small to lead to robust conclusions. Nevertheless, some inroads into this problem are now being made.

The main aims of treatment are to reduce depressive symptoms and to improve self-care, glycemic control and diabetes outcomes. A major difficulty for most clinics is the lack of readily available specialist mental health input, and this has been a disincentive for services to engage actively in tackling this important clinical problem. By contrast, guidelines are now including the issue of psychologic well-being, increasing the need for attention to be paid to it. It should be possible for most clinics to provide “first response” management for simple depressive disorders, although specialist help will still be required for more complex cases, where there is diagnostic uncertainty or lack of response to initial treatment. Assessment and management of suicide risk is a particularly important issue, although fortunately rare in most clinic settings.

Screening for depression

Given the high prevalence of depression in people with diabetes, it is recommended [20] that screening and case finding is worthwhile and this is now recommended by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK [21]. NICE recommends that health care professionals who care for or advise adults with diabetes should be alert to the development or presence of clinical or subclinical depression and anxiety. This is particularly the case where someone reports or appears to be having difficulties with self-management. Health care professionals should ensure they have appropriate diagnostic and management skills for non-severe psychologic disorders in people from different cultural backgrounds. Knowledge of appropriate counseling techniques and appropriate drug therapy is important, as well as an awareness of the need for prompt referral to specialists of those in whom psychologic difficulties continue to interfere significantly with well-being or diabetes self-management.

In the UK, GPs are now reimbursed specifically for carrying out screening in populations with chronic illness, including diabetes. There are several short screening questionnaires that can be used for this purpose including the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [22], Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [23] and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [24], although none of these have been specifically validated for use in diabetic populations, and scores may be inflated by the presence of diabetes-related symptoms. It may be better to use a very brief clinical interview using three questions [25]. Initially, the patient is asked:

- During the past month, have you been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?

- During the past month, have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?

If the answer to either of these is “yes,” the patient should then be asked if they want help with this problem. If the answer to this is also “yes,” then it is reasonable to offer treatment.

Joan is a 62-year-old married woman who has had type 2 diabetes for 15 years, which is treated by diet and oral hypoglycemic medication. She has a body mass index of 32kg/m2, and at interview was noticeably low in mood. On direct questioning, she gave a history of significant depressive symptoms lasting for several months, and had a history of previous intermittent depressive episodes dating back to the birth of her first child at the age of 24. She had low self-esteem, and admitted to bouts of “comfort eating” (mainly chocolate) to try to treat her low mood. There was no disturbance of body image. In addition, she was socially isolated, and complained of receiving little support from her husband, who was usually busy at work. Management consisted of antidepressant medication, augmented with advice and support focused on increasing socialization and resumption of pleasurable and rewarding activities, such as spending more time with her grandchildren.

Pharmacotherapy

Many treatment guidelines exist, including those from NICE [26], and similar ones from bodies such as the American Psychiatric Association. Drug treatment is the mainstay of depression management. Effective and well-tolerated antidepressant drugs are widely available and affordable. Choice of agent tends to be based on side effect profile because evidence of differential efficacy is poor. Older families of compounds such as tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors have decreased in popularity because of their toxicity, particularly in patients who might be at increased risk of heart disease.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are relatively safe and very widely used as first choice agents; however, caution is needed because there are important drug–drug interactions with some members of this class and oral hypoglycemic agents through inhibition of the cytochrome P450 3A4 and 2C9 isoenzymes (see Chapter 26). For example, the use of fluoxetine may lead to hypoglycemia [15]. Weight gain, which occurs with some antidepressants including mirtazepine, is particularly undesirable in overweight people with T2DM.

It is important to have a clear treatment target, and most guidelines now recommend that this should be complete remission of depressive symptoms. To achieve this, treatment must be sustained at an adequate dosage for a sufficient period of time. Once remission has been attained, treatment should be continued for at least 4–6 months to consolidate recovery. There is an increased risk of relapse and recurrence if the course of treatment is given at too low a dosage or for insufficient duration.

In addition to possible direct pharmacologic effects, it should be remembered that treating depression may lead to a change in the patient’s behavior and routine that may require adjustment of the diabetic regimen. For example, if the patient’s appetite improves, insulin requirements may increase; if the patient becomes more active, they may decrease. It is likely, however, that improvement in depressive symptoms alone will not translate automatically into improved self-care and diabetes outcomes. Additional attention to diabetes management is required as the depression improves.

Clinical management

In most health care systems, depression is managed mostly within primary care by family physicians or GPs. Much emphasis has been placed in recent years on the delivery of evidence-based practice, and this has led to a proliferation of guidelines and educational support designed to improve quality of primary care. In the USA, a case management model known as “collaborative care” has been pursued, whereby family physicians are supported in case management by specialist mental health teams. This approach has been shown to be clinically useful and cost-effective [27,28]. Recently, a large study, the Pathways study [29], has attempted to address the question of whether or not this approach can improve outcomes for patients with both diabetes and depression. In this study over 300 patients were randomly allocated to receive the intensified case management approach or usual care. Contrary to expectations, although depression outcomes were improved, no concomitant improvements in glycemic control were observed over a 12-month period. This finding suggests that when treating depression in people with diabetes, attention also needs to be paid to modifications that are needed in the diabetes regimen such as adjustment of diet, activity and medication if the best possible outcomes are to be attained. Such integrated approaches to management are all too rare at the present time.

Psychologic treatment

The other important aspect of management for depression that has been widely evaluated in diabetic populations is psychologic treatment, which can take a variety of forms. There is some confusion in the literature between approaches that could be broadly described as “educational” – that is, largely based on improving knowledge and understanding of diabetes management – and those with a more psychologic or behavioral basis, such as cognitive–behavior therapy. For most patients with suboptimal self-care, it appears that lack of knowledge of their condition is not the most important cause; rather there are more complex causes, which may have their origins in early life experiences or in current stressful events or circumstances, and it is these that psychologic treatments seek to address.

Educational approaches could be broadly divided into “didactic” and “enhanced”; in the latter form the giving of information and advice is supplemented with behavioral instruction, development of skills such as problem-solving and a range of other techniques such as biofeedback or relaxation. Thus, the boundary between educative approaches and formal psychotherapy has become blurred, and this creates difficulties in evaluating the available literature. The consensus from systematic reviews is that such interventions can improve glycemic control, albeit with a modest effect size of about 0.3 – equivalent to a reduction in HbA1c of around 0.6% (7mmol/mol) – and can also reduce psychologic distress [30].

There are few trials that have set out to test directly the efficacy of psychologic treatment in treating depression in people with diabetes. Studies of otherwise healthy subjects with depression show that several forms of treatment including cognitive–behavioral therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive–analytic therapy can all be of benefit. A recent systematic review evaluated the efficacy of psychologic interventions aimed primarily at improving glycemic control in people with T2DM [30], and found that benefits were seen in terms of reduced psychologic distress and improved long-term glycemic control.

Given that psychologic treatments are potentially very effective, but expensive and limited in availability, there is an urgent need for more evaluation of their benefits and applicability. In the UK, there is currently a large program evaluating the benefits of widening access to psychologic treatment for depression, and a similar initiative in the case of diabetes is warranted. Unfortunately, it appears as if availability of such treatments to people with diabetes is actually decreasing within the UK [31].

Psychotic disorders

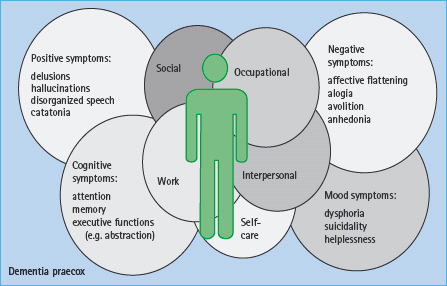

Psychotic disorders are the most serious forms of illness within the mental health field, and are often also known as “severe mental illness” (SMI). (Although this term is imprecise because it is perfectly possible for patients to have equally serious forms of other non-psychotic types of illness.) The two main forms of psychotic disorder in working age adults are schizophrenia and bipolar mood disorder or “manic depression.” The impact of these disorders on patients’ well-being and functioning is particularly severe because of the presence of psychotic symptoms including delusions and hallucinations which have a profound effect on any or all aspects of daily life (Figure 55.1). When they co-occur with a chronic physical illness, they can create significant management challenges, and such patients are amongst the most complex that health care systems encounter.

It has been noted for over a century that abnormalities of glucose metabolism are more common in those with this type of mental illness [32], although only in recent years have efforts been made to establish the precise nature of this association. The situation is complicated by the fact that some forms of treatment for these disorders may also affect metabolic health. It is known that patients with such disorders have reduced life expectancy, and much of the excess early mortality results from physical disease including diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Intensified efforts to improve the physical health of people with long-term mental illness are now underway in most countries, with detection and management of metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors and diabetes at their core [33].

Case definitions

Diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia are shown in Table 55.2. It can be seen that the illness is characterized by psychotic symptoms (delusions, hallucinations), disorganization of speech and other behavior, and so-called “negative” symptoms which include loss of drive and blunting of affect. In the longer term, schizophrenia is also associated with cognitive decline. The illness has marked effects on daily functioning, tends to run a chronic clinical course and most patients with the condition will be under the long-term care of specialist mental health services.

Table 55.2 DSM-IV schizophrenia.

| 1 Two or more of the following symptoms: (i) Delusions (ii) Hallucinations (iii) Disorganized speech (iv) Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior (v) Negative symptoms (affective flattening, alogia or avolition) |

| 2 Social/occupational dysfunction |

| 3 Features continuously present for at least 6 months |

Bipolar disorder is characterized by the occurrence of one or more episodes of mania (elevated mood), with or without a previous history of depressive episodes. Criteria for a manic episode are shown in Table 55.3. The strict diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorders are complex, and there is a degree of overlap with schizophrenia, such that some patients may be characterized as having a “schizo-affective” disorder.

Table 55.3 DSM-IV manic episode.

| 1 A distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive or irritable mood, lasting at least 1 week |

| 2 During the period of mood disturbance, three or more of the following symptoms have persisted (four if mood only irritable): (i) Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity (ii) Decreased need for sleep (iii) More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking (iv) Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing (v) Distractibility (vi) Increase in goal – directed activity or psychomotor agitation (vii) Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have high potential for painful consequences (e.g. spending, sexual activity) |

| 3 Marked impairment in occupational functioning or in usual social activities or relationships with others, or need for hospitalization to prevent harm to self or others, or psychotic symptoms |

Epidemiology

Schizophrenia is estimated to have a point prevalence of 1–7/1000 in the general population, with an annual incidence of 13–70/100 000 and a lifetime risk of 1–2%. Strikingly, this varies very little across the countries of the world. The clinical course of the illness is variable, ranging from a single brief episode (rarely) to a lifelong illness with marked deterioration over time. There are many theories about the causation of schizophrenia. It has a marked genetic risk profile, but is also associated with early cerebral insults (e.g. birth anoxia) and environmental stress.

Bipolar disorder is much less common than unipolar depression, with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 0.5–1.0%. Again, genetic factors are thought to have an important role in the etiology of bipolar disorders, which are among the most heritable of psychiatric disorders.

Mortality of people with psychotic illnesses

The fact that people with psychotic disorders have premature mortality has long been known. A landmark study in this area was that by Brown et al. [34], who showed that the standardized mortality ratio of psychiatric patients was increased threefold, and life expectancy reduced by 10–20 years. Although suicide and accidents were important causes of death, “natural causes” accounted for the majority of the excess mortality in this population.

A difficulty in the interpretation of this finding arises from the fact that patients with long-term mental illness are exposed to a wide range of different risk factors from those of the general population. Older studies suggested that hospitalization itself may have been a risk. Most patients are now cared for in community settings, but there are still marked differences in lifestyle, with psychiatric patients being more likely to smoke, being less active and having different diets from the general population, as well as being exposed to a range of pharmacologic agents. Disentangling risks associated with the disease, its treatment and genetic and lifestyle factors has proved to be particularly challenging [35].

As is the case for schizophrenia, there is growing evidence that patients with bipolar illness also have increased all-cause mortality, and evidence of increased cardiovascular disease, when compared with the general population. Again the findings of longitudinal studies in the face of confounders such as lifestyle differences and the effects of treatments can be difficult to interpret. It is likely that those patients with bipolar illness who are exposed to long-term use of antipsychotic drugs (the majority) will have similar outcomes to those of patients with schizophrenia. Other drugs used in bipolar patients such as lithium and sodium valproate are also associated with weight gain, but there has been much less research on their wider metabolic effects to date.

Psychotic disorders and their treatment as a risk factor for diabetes

Papers commenting on the association between schizophrenia and diabetes date back to at least the early part of the 20th century, but the volume of literature exploded in the early years of the 21st century, largely driven by marketing claims related to different antipsychotic drugs. Of course, the early papers demonstrating the association date from the period before the availability of these agents, and provide some of the best evidence we have of an association with the disease alone [32]. This has been supplemented more recently by a small number of studies of drug-naïve patients, but such studies are now very difficult to undertake because of the ethical difficulties of leaving people untreated [36]. Another boost to publication rates occurred when the first antipsychotic agents, the phenothiazines, came into widespread clinical use in the 1950s and 1960s, with many reports of”phenothiazine diabetes” appearing. Unfortunately, interpretation of older studies is hampered by the different diagnostic practices in use for both diabetic and psychotic disorders.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree