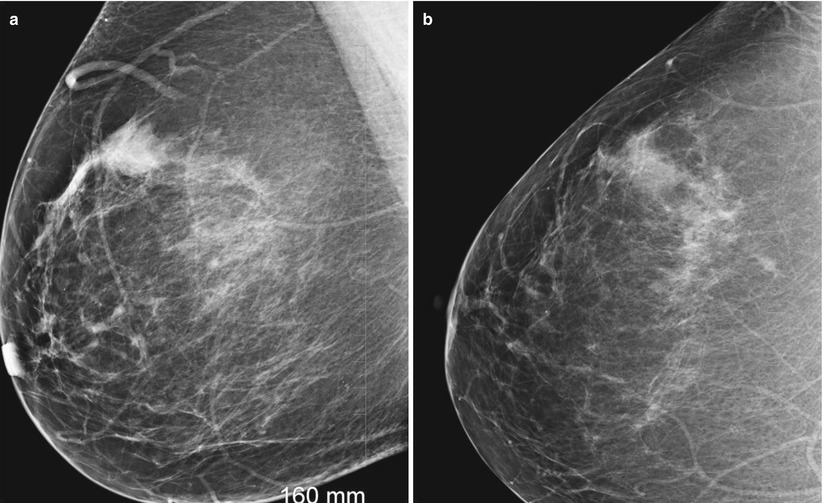

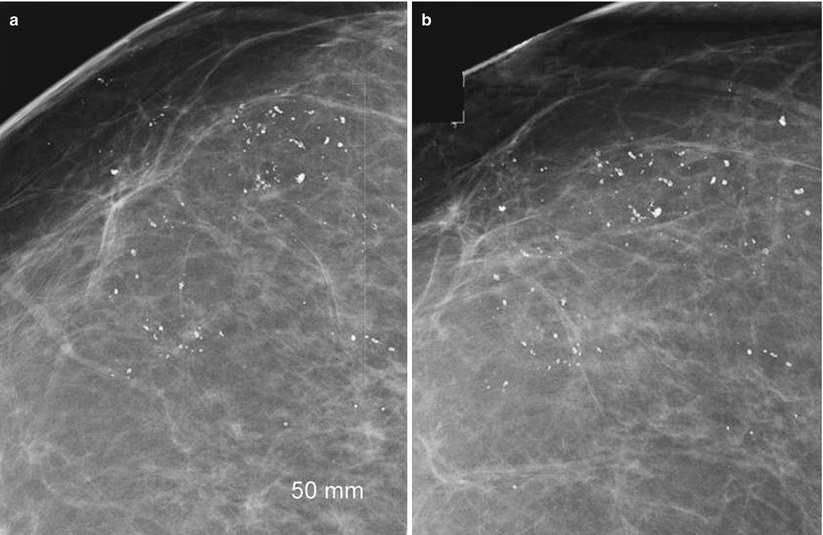

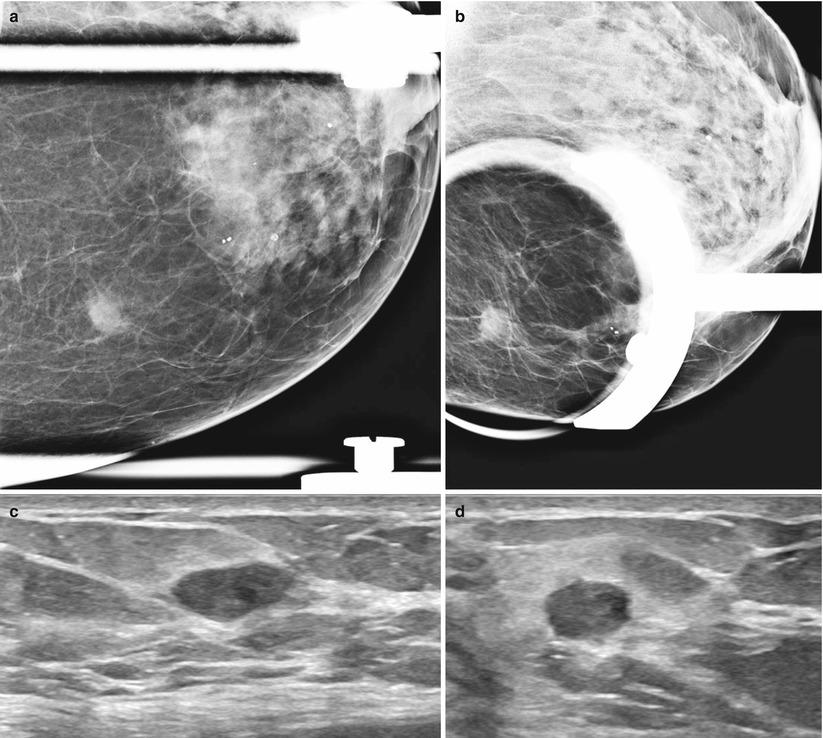

Fig. 6.1

Multiple bilateral masses in a 54-year-old woman categorized as benign findings. (a) Mediolateral oblique view demonstrates multiple masses of varying size (arrows) with a similar appearance some which demonstrate the classic appearance of coarse popcorn calcifications characteristic of calcified benign fibroadenomas. (b) Craniocaudal views demonstrate multiple masses of varying size with a similar appearance some which demonstrate the classic appearance of coarse popcorn calcifications characteristic of calcified benign fibroadenomas

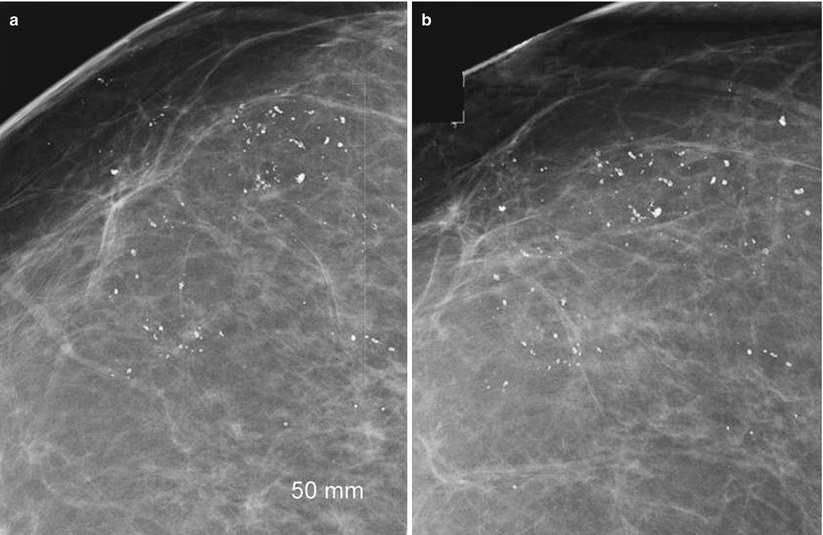

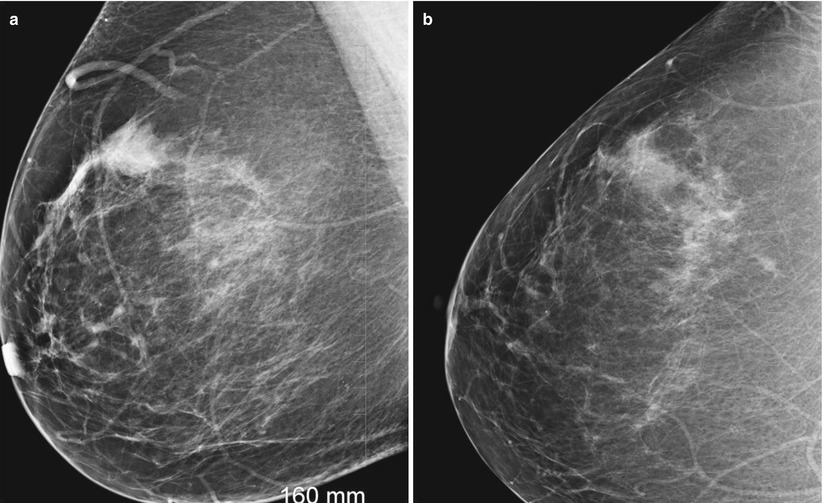

Fig. 6.2

Global asymmetry. (a) Right breast MLO view demonstrates greater volume of tissue in the central breast. (b) Left breast MLO view demonstrates lesser volume of tissue in the breast compared to the right

Box 6.1. Mammographic Findings That Are Appropriate for Short-Interval Surveillance

1. Localized |

Clusters of round or oval calcifications [38.8 %]a |

Noncalcified nonpalpable masses with well-defined margins and round, oval, or gently lobulated [18.5 %] |

Focal asymmetry [14.1 %] |

Miscellaneous: single dilated duct, architectural distortion at biopsy sites [1.3 %] |

2. Generalized |

Multiple tiny calcifications randomly distributed throughout both breast [16.4 %] |

Multiple clusters of calcifications [3 %] |

Multiple masses with similar appearance distributed throughout both breast [7.9 %] |

Box 6.2. Mammographic Findings That Are Clearly Benign and Requiring No Follow-Up

1. Dermal calcifications |

2. Vascular calcifications |

3. Mass with milk of calcium |

4. Characteristic calcified fibroadenoma |

5. Sutural calcifications |

6. Rodlike calcifications often bilateral associated with duct ectasia |

7. Fat density masses |

8. Lymph nodes |

9. Multiple bilateral similar appearing masses |

Diagnostic workup for findings that are believed to have a low probability of malignancy may include spot compression views with or without magnification. It is important to note that palpable abnormities are excluded in the probably benign category and so are findings that demonstrate interval change. The mammographic signs that are appropriately assigned as being probably benign with a low likelihood for malignancy after additional workup can be grouped under two headings, one that includes findings that are focally distributed and confined to one segment and a second group that includes diffusely distributed findings.

The focal group includes a cluster of five or more calcifications that on magnification views are round or oval. Calcifications that are dense distributed in a regional or diffuse manner (Fig. 6.3a, b).Non-calcified masses with a round oval or gently lobulated shape, and margins that are seen clearly and are well defined [2]. Focal asymmetries that are non-palpable, clearly seen on two views and with concave margins and interspersed with fat (Fig. 6.4a, b). Also included in the focal group are several miscellaneous findings such a single dilated duct without a history of a nipple discharge, subtle areas of architectural distortions occurring at known biopsy sites and unassociated with central area of increased density. When two such clustered calcifications or nodules are seen, they are to be reported as one case.

Fig. 6.3

A 45-year-old recalled for calcifications and categorized as probably benign. (a) Spot compression magnification views in the craniocaudal projection demonstrate dense macrocalcifications in a regional distribution appropriately classified as probably benign with short-interval follow-up recommendation. (b) Spot compression magnification views in the mediolateral projection demonstrate dense macrocalcifications in a regional distribution

Fig. 6.4

Focal asymmetry seen on a baseline mammogram in an asymptomatic 43-year-old. Sonogram (not shown) did not demonstrate an abnormal finding. A probably benign finding assessment was given with a recommendation for a short-interval follow-up. (a) Mediolateral oblique view demonstrates a focal asymmetry in the upper breast. (b) Craniocaudal view demonstrates a focal asymmetry in the outer breast not associated with calcifications, distortion, or a mass

The second group of probably benign abnormalities includes abnormalities that are diffusely distributed and consist of findings of multiple more than three lesions either tiny calcifications or nodules randomly distributed throughout both breasts. These findings are characterized by being of similar appearance. The calcifications may consist of diffusely scattered types or multiple clusters of calcifications. Again any abnormality that is associated with a palpable finding is excluded, as are those findings that demonstrate interval change whenever prior mammograms are available for comparison. An initial study of 90 such low suspicion lesions that were followed for at least 20 months or biopsied, one cancer was reported [1]. The validity of short-interval follow-up was for the first time proven by Sickles [2]. In a study of 3,184 cases that fulfilled these criteria to be assigned into a short-interval follow-up group, there were 17 cancers. 3,184 cases represented 11.2 % of the screening mammograms during the study period of 8.5 years. Tiny calcifications were the most frequently encountered findings [58.2 %] followed by well-defined nodules [26.4 %] [2]. Seventeen cancers were detected at follow-up corresponding to a malignancy rate of only 0.5 % in the study group. Fifteen of these 17 were biopsied based on interval growth during follow-up surveillance. None of the lesions that were biopsied despite displaying a stable appearance demonstrated a malignant histology. The majority of cancers were solitary circumscribed noncalcified masses (12/17). For noncalcified circumscribed masses, the malignancy rate was hence 2 %, higher than for the entire group although still within the acceptable range for short-interval follow-up [2]. Two circumscribed masses became palpable and hence biopsied with a malignant diagnosis. Two of the 17 cancers had metastasis to one node and none had systemic metastasis.

Similar results have been shown by others who have undertaken such studies to test the validity of short-interval follow-up for lesions with low probability for breast cancer [3–5]. In a study of 21,885 mammograms, 558 [2.5 %] abnormalities were categorized as probably benign with a malignancy rate of only 0.47 % [3]. In another study of 795 probably benign lesions representing 5.8 % of screening mammograms, the malignancy rate was 0.3 %. The probably benign abnormalities were followed for 2 years. Two cancers were seen in the low-suspicion group: one was a ductal carcinoma in situ and another 7 mm invasive cancer [4].

The value of a consensus opinion among two breast imagers in categorizing calcifications as being probably benign or suspicious enough to biopsy was studied prospectively using standard criteria. This study included for short-interval follow-up, 490 cases with clustered calcifications, 411 of which were single clusters and 81 had multiple clusters were subjected to a short-interval surveillance [6]. The malignancy rate was 0.5 % and both cases were DCIS that was diagnosed at 12 months. Among the calcifications that were deemed suspicious with a recommendation for biopsy, positive biopsy rate was 29 % [6]. The authors concluded that consensus review using standardized criteria by two breast imagers is a safe follow-up option.

In a study of 544 lesions that represented 3 % of screening mammograms, the malignancy rate was 0.4 %. The cancer rate among those cases undergoing biopsy due to interval progression at two-year follow-up was 14 % [5].In this study masses formed the most common finding [40 %] followed by focal asymmetry [26 %] and calcifications [17 %].

Short-Interval Surveillance Follow-Up Protocol and Rate of Compliance

In the study by Sickles, initial follow-up was with a unilateral mammogram at 6 months which was then followed by a bilateral mammogram at 6–12 months depending on age appropriate screening protocol, followed by two more annual follow-ups for a total of four follow-up examinations spanning up to 3.5 years. In his study the compliance rate decreased at each of the follow-up exam with compliance dropping to 66 % for the fourth follow-up exam [2]. Others have reported a compliance rate of 94.5–96 % [3–5].

Notwithstanding the extremely low incidence of malignancy among probably benign lesions that underwent surveillance based on these studies, one does encounter a higher incidence of cancers in some practices among those lesions that are categorized as probably benign. This is often due to failure to use the criteria for placing abnormalities in the probably benign category. In one reported series there were 51 malignancies identified in a group of 178 biopsies performed in patients who were assigned a probably benign assessment. On review of these findings, it was noted none of the findings fulfilled strict criteria needed to be placed in a short-interval surveillance group [7]. Calcifications were the most frequent findings in those abnormalities that proved malignant and were seen in 45 % of these cases, followed by noncalcified masses and focal asymmetry in 24 % of cases.

Probably Benign Findings on Breast Ultrasound

Stavros and others in a prospective study were able to predict benignity of a solid mass with a high degree of accuracy using morphologic criteria based on a retrospective analysis [8] (Fig. 6.5). In their series the negative predictive value for benignity was 99.5 % and was high enough to avoid biopsy. In practice these strict criteria may not be strictly adhered to while assigning solid masses to the probably benign category [9–12]. Also to note that unlike with mammography, the prospective study on probably benign category for ultrasound abnormalities was studied in a group of patients who had both palpable and nonpalpable abnormalities [8].

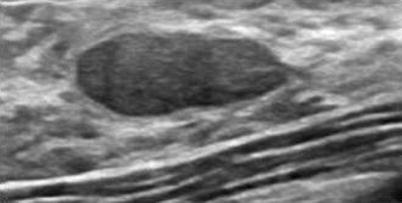

Fig. 6.5

Ultrasound demonstrates a non-palpable ovoid mass with circumscribed borders and a thin echogenic capsule considered probably benign with a recommendation for a short-interval follow-up in a 44-year-old woman seen as an incidental finding during evaluation for breast pain

The validity of the use of probably benign assignment for ultrasound-detected solid masses was studied in a series of 920 solid nodules assigned to the probably benign category based on established criteria. In this series 40.9 % of the solid masses did not fulfill the strict criteria needed for categorizing a mass as being benign. All 14 cancers that were diagnosed in the probably benign group in this study belonged to the group that subsequently was categorized as suspicious [9]. Nevertheless the malignancy rate among these 920 solid nodules was still an acceptable 1.5 % and also to be noted, 8 of the 14 cancers were palpable [9]. For ultrasound-detected masses the criteria for biopsy of a lesion placed in the probably benign finding group are either an increase in diameter beyond 10 % or change in margin characteristics on a follow-up examination [9]. Stable appearance at 2 years leads to a downgrade in final assessment category to a BI-RADS 2 [9]. The cost-effectiveness of follow-up of solid masses with benign features as an alternate to biopsy has been studied and reported to lead a reduction of cost by a third [13]. Recent studies have validated the use of probably benign assessment category for ultrasound-detected solid masses [14, 15]. The malignancy rate for lesions categorized as probably benign is still low and well below the accepted 2 % rate. A series of 4,000 women reported a malignancy rate of 0.8 %. As reported by others on retrospective analysis of the features, 29/32 [90.6 %] were incorrectly classified as benign and the error was mostly due to lack of appreciation of suspicious margin characteristics [14]. The malignancy rate among the probably benign lesions was higher among the lesions that were palpable, 2.4 % [21 of 859] compared to 0.4 % [11 of 3141] among nonpalpable lesions. In a study of 288 probably benign lesions that underwent immediate histological diagnosis, only three cancers were found for a malignancy rate of 1 % which was again within the acceptable range of 2 %. Two of these three cancers was ductal carcinoma in situ and one was an invasive ductal cancer. There were 195 masses in the study group [15]. Sonographic criteria for classifying a solid mass as benign were presence of circumscribed margins, round, oval, or slightly lobulated shape, wider than tall with parallel orientation to the skin surface, internal echotexture that was iso- or slightly hypoechoic to subcutaneous fat and with normal through transmission of sound. As in the study published by Stavros and others, size of the solid mass was considered a criterion for exclusion [8, 15]. Also included in the follow-up category were sonographic findings of hypoechoic masslike abnormalities with low-level internal echoes consistent with complicated and clustered microcysts. It is, however, important to follow these criteria strictly when categorizing as probably benign. Analysis of the margin characteristics is critical and dependency only on presence of an ovoid shape may lead to misdiagnosis (Fig. 6.6a–d).

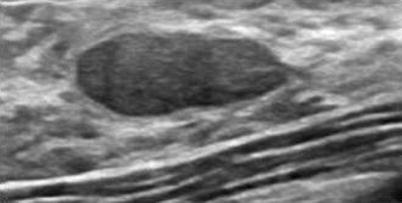

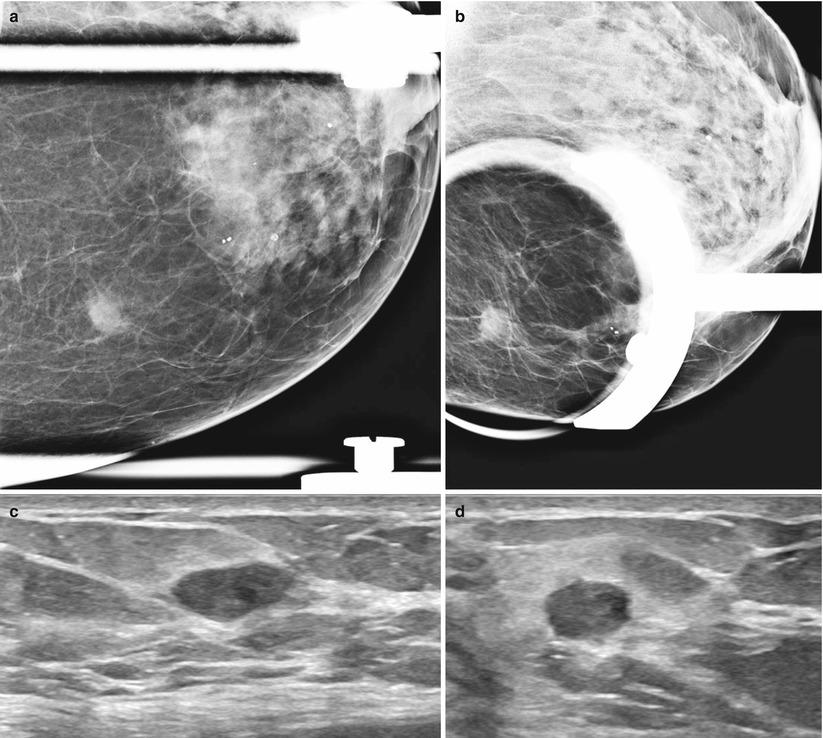

Fig. 6.6

A 44-year-old with a non-palpable solid mass incorrectly characterized as probably benign solid mass based on sonographic features histologically proven to be an invasive ductal cancer at follow-up. (c) Ultrasound in the radial plane demonstrates an ovoid circumscribed solid mass. (d) Ultrasound in the antiradial plane demonstrates irregular and ill-defined borders on close inspection. (a) Spot compression magnification views demonstrate a focal asymmetry with ill-defined borders. (b) Spot compression magnification views demonstrate a focal asymmetry with ill-defined borders

The Case Against Short-Interval Follow-Up of Abnormalities in the Breast

Unnecessary patient anxiety has been cited as a potential deterrent for short-interval follow-up resulting from not knowing the possible outcome and living with the possibility of a very small albeit real risk of having a malignant lesion in the breast [16]. However, a study that assessed the level of anxiety among women who underwent biopsy and compared it to women who had a follow-up found that the women in the biopsy group experienced a higher level of anxiety than those in the follow-up group [17]. Hall points out that the number of screening mammograms that were assigned to the BI-RADS 3 category is declining [18]. In Sickles’ original paper validating the low likelihood of malignancy in the probably benign lesions, 11.6 % of mammograms were placed in the short-interval follow-up group, and this percentage decreased to 1.2 % [2, 19]. The relatively more frequent use of this category in the USA compared to Europe may also be in part because of the heightened risk of a malpractice lawsuit in this country [18]. An additional consideration is masses versus calcifications. It has been suggested that it is more prudent to follow nonpalpable nodules than calcifications since growth of low-grade cancers among nodules is more predictable and easier to identify at follow-up compared to microcalcifications related to low-grade DCIS which may remain unchanged for years [18].

Screening mammography has a conflicting challenge of having to detect as high percentage of early-stage breast cancers as possible while causing as little harm as possible to the vast number of women that are screened and do not have breast cancer [20]. Rubin questions the need for short-interval surveillance and whether the follow-up should be 12 months instead of 6 months. She points out that unlike as was proposed by Sickles, many radiologists perform 6-month follow-up for the entire course of 3 and sometimes up to 5 years [2, 20]. Although the rate of immediate biopsy resulting from a probably benign assessment in Sickles study was only 0.4 % in most practices, it is considerably higher [2, 20]. There is always a problem with who discusses the results with the patient; clinicians are often uncomfortable with the probably benign assessment and not able to explain the findings to the patient and depending on level of patient anxiety may prompt referral to a surgeon for a biopsy. Probably benign assessment can also trigger a desire to seek a second opinion [20]. The guidelines from the European Society of Breast Imaging for Diagnostic Interventional Breast Procedures recommend biopsy as an option to short-interval follow-up [21]. Studies conducted in the UK have shown that early recall is considered more stressful than biopsy both in the short and long term [22, 23].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree