Abstract

In clinical practice, the use of preoperative or neoadjuvant chemotherapy for the treatment of inoperable and operable breast cancer is currently well established. Once reserved for the treatment of locally advanced inoperable tumors, the neoadjuvant treatment strategy has been increasingly employed in operable breast cancer backed by strong rationale. This strategy offers a number of advantages over adjuvant therapy, with in vivo assessment of tumor response and tumor downstaging to enable breast preservation ranking among the most important. The neoadjuvant strategy has also shown great potential as a platform for drug development, and this has led the US Food and Drug Administration to consider the rate of pathologic complete response (pCR) to neoadjuvant therapy as an surrogate end point for long-term outcomes to support accelerated drug approval in high-risk early-stage breast cancer. It has been clearly established that long-term outcomes are similar whether treatment is given preoperatively or postoperatively and that a pCR at the time of surgery is associated with a favorable outcome in all patients who achieve it.

Although the neoadjuvant approach is commonly employed in clinical practice today for breast cancer patients with operable stage IIA (T2N0M0), stage IIB (T2N1M0 or T3N0M0), and stage IIIA (T3N1M0) breast cancer, it is not appropriate for all patients. Accurate clinical staging at baseline before initiation of preoperative systemic therapy is critical for selecting optimal candidates for this approach. Ideal candidates for preoperative systemic therapy should have a palpable breast tumor that is easily clinically assessable. Patients with extensive in situ disease when the extent of invasive disease is not well defined are not candidates for preoperative systemic therapy. Likewise, patients with a poorly delineated extent of tumor preoperatively are poor candidates for this approach. Although infrequent, clinical disease progression can occur during neoadjuvant systemic therapy, and patients with operable disease should be taken immediately to surgery. This chapter reviews key principles of preoperative therapy in early-stage operable breast cancer and highlights the current importance of this strategy as a platform for clinical trials and drug development.

Keywords

neoadjuvant therapy, preoperative therapy, operable breast cancer, early-stage breast cancer, chemotherapy, endocrine therapy

Coming of Age for Preoperative Systemic Therapy in Operable Breast Cancer

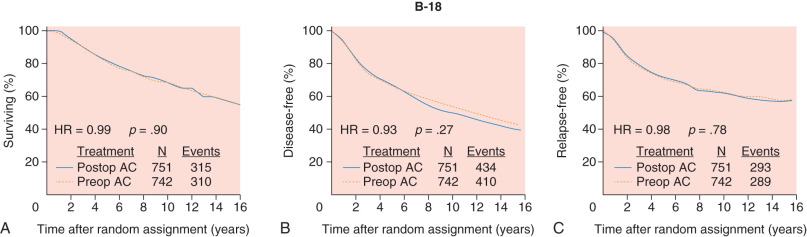

The concept of using preoperative or neoadjuvant systemic therapy was first put forth many decades ago for the treatment of locally advanced inoperable breast tumors. Early experiences showed that this approach enabled ultimate operability and resulted in highly effective local control. In 1988, the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) launched the B-18 clinical trial to evaluate preoperative systemic chemotherapy versus postoperative systemic therapy for the treatment of patients with stage I and II operable breast cancer. The goals of the B-18 study were ambitious and aimed to determine whether preoperative chemotherapy results in improved disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with postoperative adjuvant therapy, if response to preoperative therapy was predictive of outcome, and also whether this approach could result in improved rates of breast preservation. More than 1500 patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to receive doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide for four cycles before or after surgery. The initial report from the B-18 study showed no difference between the two groups in regards to DFS or OS, and many more patients in the preoperative group underwent breast preservation surgery. After 16 years of median follow-up, no statistically significant differences between the two groups with regard to DFS and OS were observed ( Fig. 62.1 ), although there was a trend toward better outcomes in women aged less than 50 years treated with preoperative therapy. A subsequent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials including nearly 4000 patients with both operable and inoperable nonmetastatic breast cancer confirmed these findings, with the notable exception that locoregional relapses were increased among patients receiving preoperative therapy, particularly in studies where radiotherapy was given in the absence of surgery.

These data helped to establish the safety and efficacy of preoperative systemic therapy in early-stage operable breast cancer. This approach is commonly used in clinical practice today for breast cancer patients with operable stage IIA (T2N0M0), stage IIB (T2N1M0 or T3N0M0), and stage IIIA (T3N1M0) breast cancer. To deliver preoperative systemic therapy optimally in patients with operable early-stage breast cancer, appropriate patient selection and on treatment monitoring are paramount. This chapter reviews these principles of neoadjuvant systemic therapy and highlights the current importance of this strategy as a platform for clinical trials and drug development ( Box 62.1 ).

- •

Preoperative therapy downstages primary breast tumors to enable breast conservation.

- •

Preoperative therapy provides an in vivo assessment of therapy response.

- •

Association between pCR and prognosis is strongest in triple-negative and HER2-positive cancers.

- •

- •

Accurate clinical staging at baseline is critical before embarking on preoperative therapy:

- •

Possible overtreatment with systemic therapy if clinical stage is overestimated;

- •

Possible undertreatment locoregionally with radiotherapy if clinical stage is underestimated; or

- •

Patients with extensive in situ disease where the extent of invasive disease is unclear, those with nonpalpable tumors and those with a poorly delineated extent of tumor are noncandidates for a preoperative approach.

- •

- •

Preoperative systemic therapy is an option for clinical stage IIA (T2N0M0), stage IIB (T2N1M0 or T3N0M0), and stage IIIA (T3N1M0) breast cancer, particularly in patients with

- •

a large primary tumor relative to breast size in a patient who desires breast conservation or

- •

Tumor subtypes associated with a high probability of response.

- •

- •

On-therapy assessment of response to therapy is key.

- •

Routine imaging is not advised.

- •

Patients experiencing clinical progression should be taken immediately to surgery.

- •

- •

A sentinel node biopsy or axillary lymph node dissection can be considered in patients with clinically positive nodes at baseline who convert to clinically negative posttreatment.

- •

Locoregional principles should be applied in the same manner as in patients treated with adjuvant therapy.

- •

Decisions regarding the need for radiotherapy should be based on baseline clinical stage.

- •

Rationale for Preoperative Systemic Therapy

In addition to demonstrating equivalent long-term outcomes with preoperative and postoperative systemic therapy and demonstrating improvement in rates of breast conservation, clinical experiences from clinical trials such as NSABP B-18 and others clearly demonstrated that the delivery of neoadjuvant therapy offers an important opportunity to assess therapy response in an individual patient. Importantly, it was observed that the attainment of a pathologic complete response (pCR) at the time of surgery is a strong surrogate for improved DFS in responders. In the recent Collaborative Trials in Neoadjuvant Breast Cancer (CTNeoBC) pooled analysis of 12 randomized neoadjuvant clinical trials including nearly 12,000 patients, event-free survival (hazard ratio [HR] 0.48; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.43–0.54) and OS (HR 0.36; 95% CI 0.31–0.42) were higher in patients who achieved a pCR defined as an absence of invasive disease in the breast and axillary nodes at the time of surgery, irrespective of the presence of in situ disease. Importantly, this analysis and others have demonstrated that the correlation between pCR and event-free survival varies by breast cancer subtype. The strongest prognostic correlation exists for hormone receptor–negative, HER2-positive and triple-negative tumors. The correlation between pCR and long-term outcome is weakest for ER-positive disease. Tumor grade is another factor of significance influencing the likelihood of pCR, with high-grade tumors having significantly higher rates of pCR compared with low- and intermediate-grade tumors.

On the basis of these observations, it was proposed that pCR could serve as a surrogate end point for prediction of long-term clinical benefit in early breast cancer. Until recently, our standard drug development strategy in breast cancer relied on testing novel agents first in the metastatic setting and later approving these agents in the adjuvant setting after completion of large and lengthy adjuvant studies. To accelerate drug development in high-risk early-breast cancer, an accelerated US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval pathway using the neoadjuvant platform in early-breast cancer was proposed by the FDA in 2012. The idea was that an assessment of a novel agent’s activity, when added to standard chemotherapy in early breast cancer, could be carried out in a smaller number of patients and over a much condensed time period compared with the standard adjuvant approach. A major goal of the CTNeoBC pooled analysis was to examine the potential of pCR as a surrogate end point for long-term outcomes. Although a correlation between pCR and long-term outcomes could be observed at the individual patient level, the pooled analysis could not establish a trial level correlation between pCR and long-term outcome. Despite this, the FDA took the position that if a novel agent produces a marked absolute increase in the frequency of pCR compared with standard therapy, that the agent could also be considered to be reasonably likely to result in long-term improvements in event-free and OS. On September 30, 2013, the FDA approved pertuzumab as part of a complete neoadjuvant regimen for patients with stage II–III early breast cancer. Pertuzumab was the first drug approved using this neoadjuvant approval pathway based on pCR end points from two phase II studies.

In addition to providing a pathway to evaluate novel agents with the possibility of accelerated FDA approval of novel agents, the neoadjuvant setting offers additional clinical trial opportunities. Among patients with triple-negative or hormone receptor–negative, HER2+ breast cancer, for example, those patients who fail to achieve pCR have a significantly elevated risk of early relapse and death from breast cancer. The CREATE-X clinical trial recently showed a DFS and OS advantage with capecitabine when delivered to high-risk HER2-negative early breast cancer patients with residual disease after standard neoadjuvant combination chemotherapy. Current studies are underway to explore novel agents in the adjuvant setting when residual disease is detected after standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy. In addition, the neoadjuvant platform offers an opportunity for pre- and posttreatment tissue collection and enables the assessment of new tissue and imaging-based biomarkers. Finally, the results of neoadjuvant trials can help to inform the design and conduct of adjuvant studies, thus sparing time and costs associated with negative adjuvant studies.

In addition to the advantages already noted, for patients who will absolutely require systemic therapy, the use of preoperative systemic therapy may allow patients to begin their breast cancer therapy without excessive delays while waiting for results of genetic testing or in cases in which delays may be introduced due to planning required for breast reconstruction in patients electing to undergo mastectomy surgery. Recent data from a single institution suggest that a delay in time to chemotherapy can affect survival outcomes in stage I–III early breast cancer, particularly in those with high-risk breast cancer subtypes. Specifically, initiation of chemotherapy 61 days or more after surgery was associated with adverse outcomes among patients with stage II (distant relapse-free survival HR 1.20; 95% CI 1.02–1.43) and stage III (overall survival HR = 1.76; 95% CI 1.26–2.46; and distant relapse-free survival HR 1.36; 95% CI 1.02–1.80) breast cancer. Patients starting chemotherapy 61 days or more after surgery with triple-negative tumors and those with HER2-positive tumors treated with trastuzumab had worse survival (HR 1.54; 95% CI 1.09–2.18 and HR 3.09; 95% CI 1.49–6.39, respectively) compared with those who initiated treatment in the first 30 days after surgery.

Other potential benefits of neoadjuvant systemic therapy include the possibility of sentinel lymph node biopsy only if a positive axilla is cleared with chemotherapy and the possibility of allowing for smaller radiotherapy ports or delivering less radiotherapy if axillary nodal disease is cleared with neoadjuvant therapy. This is currently being tested in the NRG 9353 (NSABP-51/RTOG 1304) trial where patients with clinical T1–3N1M0 breast cancer with biopsy-proven N1 nodal disease receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy and then, if axillary nodal involvement is negative at definitive surgery, are randomized to receive (1) postmastectomy radiotherapy versus not or (2) whole breast radiotherapy versus whole breast plus regional nodal irradiation.

Patient Selection for Preoperative Therapy in Operable Breast Cancer

Although the neoadjuvant approach is commonly used in clinical practice today for breast cancer patients with operable stage IIA (T2N0M0), stage IIB (T2N1M0 or T3N0M0), and stage IIIA (T3N1M0) breast cancer, it is not appropriate for all patients. Accurate clinical staging at baseline before initiation of preoperative systemic therapy is critical for selecting optimal candidates for this approach. Clinical stage should be calculated based on radiographic and physical examinations using the current American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Breast Cancer Guidelines recommend that suspicious lymph nodes based on imaging or physical examination findings be biopsied by core biopsy or fine-needle aspiration to document clinical nodal stage before treatment. In addition, marking of sampled lymph nodes with a tattoo or clip should be considered to allow verification that the biopsy-proven positive lymph node is removed at the time of definitive surgical resection. In patients with a clinically negative axilla, axillary ultrasound should be considered with biopsy by fine-needle aspiration or core of any lymph nodes suspicious on axillary ultrasound imaging before initiation of preoperative therapy. A core biopsy of the primary breast lesion is preferred to allow assessment of prognostic markers and an image-detectable marker or clip should be placed to demarcate the tumor bed for postsystemic therapy surgical planning. Areas suspicious for multicentric disease should be separately sampled before initiation of preoperative therapy if breast conservation surgery is being considered. For patients with clinical stage III disease or in those with clinical stage I–II disease with symptoms or signs of metastatic disease, systemic staging should be completed to rule out metastatic disease.

If clinical stage is overestimated, it is possible that the patient may be overtreated with systemic therapy. Conversely, if clinical stage is underestimated, it is possible that a patient can be undertreated locoregionally with radiotherapy. Ideal candidates for preoperative systemic therapy should have a palpable breast tumor that is easily clinically assessable. Patients with small, nonpalpable tumors are not candidates for a preoperative approach because it is important that the tumor response be assessed during therapy. Although infrequent, clinical disease progression can happen during neoadjuvant systemic therapy, and it is critical that this be promptly identified and patients with operable disease taken immediately to surgery. Patients with extensive in situ disease when the extent of invasive disease is not well defined are also not candidates for preoperative systemic therapy and are better served by upfront surgery to gain better precision in pathologic staging. Likewise, patients with a poorly delineated extent of tumor preoperatively are not candidates for preoperative systemic therapy.

Candidates for preoperative systemic therapy include patients with inoperable breast cancer on the basis of having inflammatory breast cancer with skin involvement, bulky and matted N2 axillary nodes, N3 nodal disease, and those with noninflammatory T4 tumors. In patients with operable disease, patients with clinical stage IIA (T2N0M0), stage IIB (T2N1M0 or T3N0M0), and stage IIIA (T3N1M0) breast cancer are candidates for a preoperative systemic therapy approach, particularly if the breast primary tumor is large relative to breast size in a patient who desires breast preservation. In addition, this approach is generally favored in patients with breast cancer subtypes associated with a high likelihood of response such as those with triple-negative or HER2-positive disease. In these patients, response to therapy offers more powerful prognostic information compared with patients with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree