Chapter 2 Primary Care in Developed Countries

In developed countries, persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have experienced a profound improvement in survival, mainly as a result of the widespread availability and use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). With this tremendous success and with persons living much longer, the role of long-term primary care of HIV-infected persons has taken on increased importance. In the US and other developed nations, a wide range of medical providers, including infectious diseases specialists, internists, family practitioners, physician assistants, and advanced registered nurse practitioners, now serve in the capacity as HIV primary medical care providers. Excellent primary care for HIV-infected individuals consists of competent management of both HIV-related issues, as well as those general medical issues not directly related to HIV. Fundamental elements of competent HIV-specific primary care consist of identifying HIV-infected persons, recognizing common HIV-related manifestations, performing the initial comprehensive evaluation, providing appropriate vaccinations, prescribing appropriate medications to prevent major opportunistic infections, diagnosing common opportunistic infections, initiating optimal antiretroviral therapy when indicated, and providing counseling for prevention of the transmission of HIV to others. In addition, because of the rapidly changing nature of the field of HIV, those medical providers not considered HIV experts should make every effort to remain current with updated key treatment guidelines and receive consultation advice as needed, particularly for complicated HIV-related issues, such as interpretation of resistance tests and management of serious opportunistic infections. Conversely, many HIV experts may not have expertise in general medical care, and thus should attempt to remain current on the management of common primary care problems, such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes, as well as on the provision of essential preventive medicine services. This chapter will focus on HIV-related clinical issues essential for the primary care management of HIV-infected individuals.

IDENTIFYING HIV-INFECTED PATIENTS

Unfortunately, approximately one-fourth of persons now living with HIV in the US remain unaware of their HIV infections, and many persons who eventually obtain a diagnosis of HIV do not get tested until late in the course of their disease.1 The rationale for emphasizing early diagnosis of persons with HIV infection is twofold: those individuals identified earlier in the course of their disease are likely to benefit more from antiretroviral therapy and opportunistic infection prophylaxis and, moreover, persons who are aware of their HIV status may be less likely to transmit HIV to others. Four major settings exist in which a medical provider might identify an HIV-infected individual: (1) routine HIV screening of an individual, (2) recognizing acute (primary) HIV infection, (3) recognizing a non-life-threatening HIV-related manifestation, such as oral hairy leukoplakia or oral candidiasis, and (4) diagnosing an AIDS-related complication, such as Pneumocystis pneumonia or Toxoplasma encephalitis.

During the early years of the HIV epidemic in the US, as well as in other industrialized countries, identification of HIV-infected persons focused on specific populations, particularly men who had sex with men (MSM), injection-drug users, hemophiliacs, and other blood product recipients; and these different populations were often described as ‘high-risk groups’.2,3 This terminology implies that certain individuals have greater susceptibility to HIV infection when compared with others, but as the HIV epidemic progressed, it became clear that HIV could infect persons from any population if they engaged in high-risk behavior. Thus, the HIV epidemic in the US now affects persons from a wide spectrum of socioeconomic and cultural groups. In 2003, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued recommendations to test for HIV infection in the following individuals: (1) all patients in all high HIV-prevalence clinical settings (such as a sexually transmitted diseases clinic), (2) those with risks for HIV in low-prevalence clinical settings, and (3) patients admitted to high HIV-prevalence acute care hospitals (HIV seroprevalence exceeds 1% or where the AIDS case rate exceeds 1 per 1000 discharges), and (4) all pregnant women.4 Despite these recommendations for testing, the number of undiagnosed HIV-infected persons has remained at ∼25%. Moreover, despite broad prevention efforts, the number of new HIV infections in the US has remained at ∼40 000 new cases per year, and there has been great concern that a disproportionate number of the new cases have resulted from HIV transmission from individuals who do not know they have HIV infection. These factors, when taken together, led the CDC to revamp their strategy for HIV testing and in 2006, the CDC issued sweeping new HIV testing guidelines. These new guidelines have four essential components: (1) routine voluntary HIV screening of all persons in the US aged 13–64 (not based on HIV risk or HIV prevalence), (2) repeat HIV screening at least annually in persons with ongoing risk factors, (3) opt-out testing with an opportunity for the patient to ask questions and to decline, and (4) formal consent and prevention counseling will no longer be required (Table 2-1).5 Even with the new CDC recommendations for broad HIV testing, a significant proportion of HIV-infected persons will remain undiagnosed, particularly if they do not access a healthcare system or if their medical provider fails to perform HIV testing. Since these undiagnosed individuals may present to medical care with an initial HIV-related complication, medical providers should remain alert to recognition of HIV-related clinical findings.

Table 2-1 Summary of 2006 Revised CDC Recommendations for HIV Screening

| Recommendation |

| Routine HIV voluntary screening of all persons aged 13–64 in healthcare settings Screening not based on risk or prevalence Screening performed as opt-out testing (patient advised to have test and patient can refuse test) Formal consent no longer required Prevention counseling in conjunction with HIV screening no longer required Separate recommendations apply to correctional facilities Patients with positive HIV test should be provided reliable clinical care or referred to qualified provider |

Diagnosing a patient with acute (primary) HIV has major implications for the long-term health of this person and for their risk of transmitting HIV to others. Overall, ∼40–90% of individuals who acquire HIV will have a symptomatic illness associated with this initial infection.6 Clinical manifestations of acute retroviral illness may appear within days to weeks of exposure to HIV, and most commonly occur between 2 and 6 weeks.7 The clinical presentation most often consist of a mononucleosis-like illness that includes fever, lethargy, myalgias, headache, pharyngitis, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, and a nonpruritic erythematous maculopapular rash (Table 2-2). The differential diagnosis for patients with acute retroviral syndrome is relatively broad and includes infectious mononucleosis, streptococcal pharyngitis, viral respiratory tract infections, secondary syphilis, acute toxoplasmosis, viral hepatitis, or viral meningitis (Table 2-3). Because of the nonspecific nature of the syndrome, the initial clinical findings and laboratory results can overlap with numerous other diseases; thus, the clinician should obtain relevant medical history related to a potential HIV exposure during the preceding 6–8 weeks. The diagnosis is confirmed by a positive HIV RNA assay (or p24 antigen test) in conjunction with a negative HIV antibody test (or a positive enzyme immunoassay and an indeterminate Western blot test).6 Because patients with newly acquired HIV are probably more infectious to others than at any other stage of their HIV disease course, making a diagnosis at this stage provides an opportunity to impact this patient’s potential transmission of HIV to others. In addition, if a patient with acute infection does not have a diagnosis made with this initial illness, their infection may remain unrecognized for many years and optimal medical care for their HIV illness will be delayed. A detailed discussion of acute HIV is presented in Chapter 33.

Table 2-2 Signs and Symptoms Associated With Acute Retroviral Syndrome

| Clinical Finding | Percent of Patients |

|---|---|

| Fever | >80 |

| Fatigue | >70 |

| Weight loss | 70 |

| Pharyngitis | 50–70 |

| Myalgia | 50–70 |

| Night sweats | 50 |

| Diarrhea | 50 |

| Rash | 40–80 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 40–70 |

| Headache | 32–70 |

| Nausea, vomiting | 30–60 |

| Aseptic meningitis | 24 |

| Oral or genital ulcers | 10–20 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 45 |

| Leukopenia | 40 |

| Elevated liver enzymes | 21 |

Adapted from Kahn JO, Walker BD. Acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N Engl J Med 339:33–9 1998, with permission; and Schacker T, Collier AC, Hughes J, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic features of primary HIV infection. Ann Intern Med 125:257–64, 1996. Erratum. Ann Intern Med 126:74, 1997.

Table 2-3 Differential Diagnosis of Acute Retroviral Syndrome

| Infectious mononucleosis (Epstein-Barr virus or cytomegalovirus) Toxoplasmosis Streptococcal pharyngitis Rubella Secondary syphilis Viral meningitis Other viral infections (e.g., influenza) Viral hepatitis Disseminated gonococcal infection Drug reaction |

Early manifestations of altered cell-mediated immunity may raise the clinical suspicion of HIV; furthermore, many of these common clinical manifestations require recognition and management in routine care of persons with known HIV infection. Examples of such clinical findings include oral candidiasis, molluscum contagiosum, oral hairy leukoplakia, herpes zoster, generalized lymphadenopathy, unexplained cytopenias, pneumococcal pneumonia, tuberculosis, and specifically in women, refractory vulvovaginal candidiasis, cervical dysplasia, and any stage of cervical carcinoma.8 Making a diagnosis of HIV at this stage is critical since the patient has already displayed some facet of immunosuppression and likely would need antiretroviral therapy at this stage or in the near future.

NATURAL HISTORY OF HIV

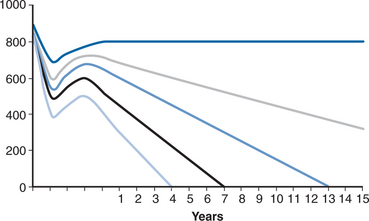

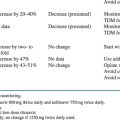

The clinical course of untreated HIV infection is now well established.9 In most cases HIV causes progressive loss of T-helper lymphocytes, which eventually renders the patient unable to mount an adequate immune response against a variety of opportunistic pathogens. The time course of this decline varies considerably from patient to patient (Fig. 2-1). Indeed, in some individuals, no apparent loss of immunologic function is detectable as long as 10 years or more after untreated infection (the so-called long-term nonprogressors). Antiretroviral drug therapy is generally not indicated for this subset of patients, as they are apparently able to control HIV replication. Conversely, some patients have very rapid progression of their disease with development of severe immune suppression within 2 years of acquiring HIV infection. In most cases, however, T-helper lymphocyte counts in untreated individuals gradually decline to the point that major HIV-related complications develop ∼7–10 years after becoming infected with HIV. The patient’s initial baseline plasma HIV RNA level (prior to starting antiretroviral therapy) serves as a powerful predictor of the pace of T-lymphocyte cell decline and subsequent risk of progression to AIDS.10 The HIV RNA value tends to remain relatively stable after the host controls the acute HIV infection, with the establishment of a type of equilibrium between viral replication on one hand and T-helper lymphocyte generation on the other, which typically occurs ∼6 months to a year after the initial infection. The decision to start HAART is based on an assessment of the likelihood of clinical progression and the risk of subsequent development of major HIV-related complications and this issue is discussed in detail in Chapter 4. Since the course of HIV disease is highly variable, individual patients will need close long-term follow-up to optimize the timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy.

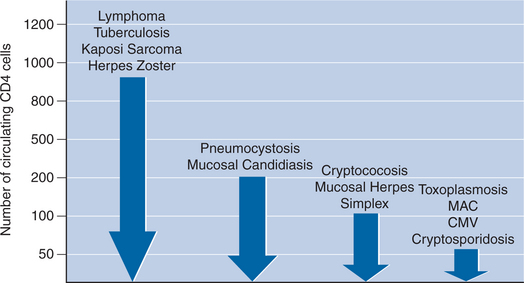

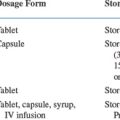

A fairly well-defined correlation exists between a patient’s T-helper lymphocyte count and the risk of developing specific infections (Fig. 2-2).11,12 In general, certain virulent bacterial pathogens, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Streptococcus pneumoniae, may cause disease in patients with relatively high CD4+ T-helper lymphocyte counts (in excess of 300 cells/μL). Other life-threatening opportunistic pathogens generally pose a threat only at levels below a certain threshold CD4+ T-helper lymphocyte count: Pneumocystis jiroveci (below 200 cells/μL), Toxoplasma gondii (below 100 cells/μL), disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex (below 50 cells/mm3), and cytomegalovirus (below 50 cells/μL).

INITIAL EVALUATION OF THE HIV-INFECTED PATIENT

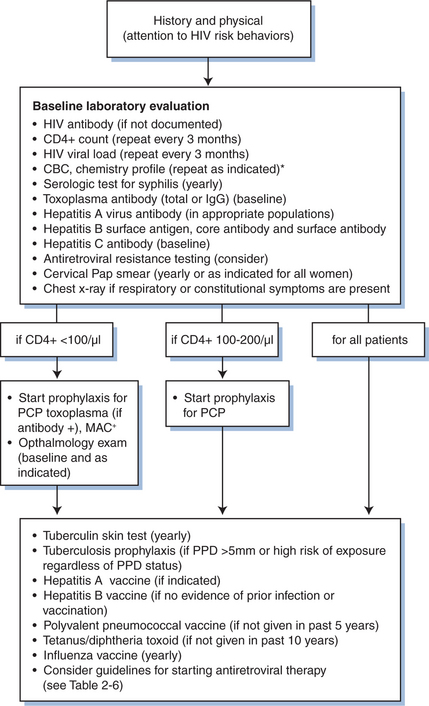

During the initial evaluation when an HIV-infected individual establishes a primary care relationship, a crucial interface takes place between the provider and the patient that may set the tone for future long-term care. In this initial encounter, the medical provider should make the most of the opportunity to establish rapport with the patient. For practical purposes, many clinicians have the initial evaluation of an HIV-infected patient include two visits that are spaced ∼1–2 weeks apart. The first visit should typically involve three key components: (1) obtaining a detailed medical history relevant to the patient’s HIV disease, (2) performing a complete physical examination, and (3) ordering relevant laboratory studies. The second visit should primarily focus on reviewing the patient’s laboratory results, estimating the stage of HIV disease based on the CD4+ T-cell count, and, if applicable, providing vaccinations, antiretroviral therapy, and prophylaxis for opportunistic infections. At either of these visits, the patient should have tuberculin skin testing performed. During both of these initial encounters, the medical provider should assess the patient’s fundamental understanding of HIV disease and address concerns or questions the patient may have. A typical flow sheet for initial evaluation of the HIV-infected patient is shown in Figure 2-3.

Medical History

During this initial evaluation, the medical provider should assess the patient’s general medical history and perform a complete review of systems, including a review of symptoms associated with earlier stage HIV-related disease, such as fever, night sweats, unanticipated weight loss, generalized lymphadenopathy, herpes zoster, diarrhea, and oral candidiasis (Table 2-4). Questions should also address history of (or active symptoms that would suggest) an AIDS-related complication, including recurrent bacterial pneumonia, Pneumocystis pneumonia, tuberculosis (including extrapulmonary disease), Toxoplasma encephalitis, cryptococcal meningitis, cytomegalovirus infection, disseminated M. avium complex infection, cervical cancer, and Kaposi sarcoma. The provider should also obtain a specific geographic history since patients may have previously become infected with a regionally prevalent fungal organism, and thus have an increased risk of developing a reactivation fungal disease, which can occur with histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and coccidioidomycosis. Because of the nature of HIV transmission, a detailed sexual and drug history (including use of recreational drugs) should also be included, and any history of specific sexually transmitted diseases or viral hepatitis should be elicited. In addition, providers should also ascertain whether patients have had a prior hepatitis A or B vaccination.

Table 2-4 Relevant Clinical History for HIV-Infected Patients

| Medical Issues |

| Prior medical, surgical, or psychiatric conditions Current medications Drug allergies Prior or current infection with tuberculosis, sexually transmitted infections, and/or viral hepatitis (A, B, or C) Reproductive health history Travel history Immunizations |

| HIV-Specific Issues |

| Duration of infection CD4 T-lymphocyte counts Plasma viral load measurements History of opportunistic infections or neoplasms Antiretroviral therapy history Prophylactic medications Nutritional history |

| Behavioral Issues |

| Prior and current alcohol and other drug use Cigarette and other nicotine use Awareness of how HIV infection is transmitted, and current pattern of risk behaviors Emotional status: presence of depression Family and other primary support systems Employment/insurance status Community involvement |

Medication and Drug History

Obtaining an accurate and thorough medication history is essential, especially if antiretroviral therapy is to be initiated. The medical provider should ask the patient about all medications being taken, including over-the-counter drugs, complementary and alternative medications, such as herbal preparations and nutritional supplements. Because many patients tend to consider herbal medications benign and do not mention their use, they should be reminded that any pharmacologically active substance might have unwanted side effects or interactions with other medications. For example, St John’s wort, which is sold over-the-counter as an antidepressant, may significantly alter the metabolism of protease inhibitors.13 Our understanding of the safety and efficacy of many alternative therapeutics remains incomplete, and thus careful monitoring should take place if the patient discloses the use of nonprescription medications. In addition to determining the patient’s medication history, the medical provider should, in a nonjudgmental fashion, obtain an accurate and detailed history regarding the use of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs. Information regarding illicit drug use may have particular relevance when considering the timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy, adherence to antiretroviral medications, and possible transmission of HIV to others.

Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination should be done at the initial visit, focusing on organ systems likely to be affected by opportunistic illnesses. Height and weight should be measured at baseline; in particular, a change in weight can be a sensitive marker of systemic illness. With regard to vital signs, fever suggests infection or an inflammatory process, and hemodynamic instability suggests hypovolemia, a serious infection, or adrenal insufficiency. A thorough skin examination should look for lesions suggestive of Kaposi sarcoma and other opportunistic illnesses. The ocular fundi should be visualized to look for retinal lesions, particularly those associated with cytomegalovirus infection, toxoplasmosis, or HIV-related lesions (see Chapter 66). In the oropharynx, candidiasis and oral hairy leukoplakia are sensitive markers of immunosuppression. Kaposi sarcoma can be observed in the mouth or on the skin. An assiduous search should be made for significantly enlarged lymph nodes in all palpable areas. Hepatomegaly or splenomegaly suggests a number of possible systemic infections, ranging from viral hepatitis to disseminated mycobacterial disease. A careful neurologic examination should also be done on all patients at baseline. A detailed anogenital examination is important, since many HIV-infected patients are also at risk for sexually transmitted diseases, including herpes simplex virus and human papilloma virus (HPV) infection. Although some experts have suggested men who engage in anal sex should have anal Pap smears checked yearly, the 2002 US Public Health Service/Infection Disease Society of America (USPHS/IDSA) Guidelines for the Prevention of Opportunistic Infections states that further studies of screening and treatment programs for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions need to be performed prior to making a recommendation for routine anal cytology screening.14

Laboratory Tests

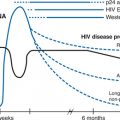

A baseline laboratory evaluation of a newly diagnosed HIV-infected patient (Fig. 2-3) should include a complete blood count, platelet count, routine serum chemistries, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and hepatic aminotransferase levels. These tests can help identify asymptomatic common co-morbid conditions, such as anemia, thrombocytopenia, HIV-associated nephropathy, and viral hepatitis, as well as to serve as a valuable baseline prior to initiating antiretroviral therapy. In addition, because antiretroviral therapy may cause or contribute to new-onset glucose intolerance or hyperlipidemia,15 patients should also be screened with fasting blood glucose and lipid determinations to determine an accurate baseline value.

The CD4+ T-lymphocyte count is the most readily available quantitative measure of the status of the cell-mediated immune system, and should be checked at baseline and every 3–4 months thereafter. The CD4+ T-lymphocyte count has a wide dynamic range in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected persons; normal values typically range from 500 to 1200 cells/μL in noninfected persons. For HIV-infected persons clinical manifestations related to cell-mediated immune dysfunction infrequently occur when CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts are greater than 350 cells/μL; herpes zoster is one major exception since it can occur at relatively high CD4+ T-cell counts. At counts less than 350 cells/μL, oral candidiasis, oral hairy leukoplakia, recurrent dermatoses, and other mucosal infections may begin to manifest and connote impaired immune function. Those patients with counts less than 200 cells/μL have severe immune dysfunction and have a significant increased risk for developing life-threatening opportunistic infections.12 Thus, in an asymptomatic patient with a stable CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of 500 cells/μL or more, it is not necessary to monitor the CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts more frequently than every 3 months, but in patients whose count are less than 350 cells/μL and show more rapid decline, more frequent monitoring may be warranted.

Similar to the monitoring of CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts, a quantitative plasma HIV RNA assay should be followed on a regular basis, typically every 3–4 months in a patient not receiving antiretroviral therapy. However, if the patient is receiving antiretroviral therapy, monitoring the HIV RNA levels more frequently may be indicated, particularly during the first 4–6 months after initiation of therapy, or when breakthrough viremia has occurred and resistance to antiretroviral medications is suspected. There are three commonly used assays that measure plasma HIV RNA and offer comparable information: polymerase chain reaction (PCR), branched DNA (bDNA), and nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) (see Chapter 1 for more detail).16 The HIV RNA level should be measured when a patient is first diagnosed, prior to any planned change in antiretroviral therapy, and at least every 4 weeks after a change until it has reached a stable level.17 For antiretroviral-naive patients with established HIV infection, baseline HIV genotypic or phenotypic resistance testing should be considered17 and many experts have increasingly begun performing resistance tests in this setting given the increased transmission of resistant HIV (see Chapter 28).18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree