Abstract

Numerous dermal diseases, including congenital anomalies, benign and malignant neoplasms, and manifestations of various dermatoses, may involve the skin of the breast. These disorders may involve solely the breast or the breast may be involved as a result of a systemic dermatosis. In reviewing a dermatologic disorder of the breast, one useful approach is to divide these diverse entities into those primary diseases that are specific, nearly specific, or common for the skin of the breast and those secondary disorders that predominantly affect other dermatologic areas of the body but affect the breast incidentally or less commonly. The decision to classify a cutaneous disease of the breast as primary versus secondary may prove difficult and, at times, is best left unstated. Both types of dermatologic disorders may also mimic primary or secondary diseases of the breast parenchyma. For all these reasons, it is important for both the breast generalist as well as the breast specialist to be versed in these primary and secondary dermatologic disorders of the breast.

Keywords

dermatologic, cutaneous, nipple, melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, psoriasis, acanthosis, dermatoses, skin

The skin of the breast consists of keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium overlying a thick fibrocollagenous dermis containing vascular and lymphatic vessels, adnexal structures, and the suspensory ligaments of Cooper. Adnexal structures, including hair follicles, apocrine and eccrine glands, and cutaneous nerves, reside within the dermis. The subcutaneous fatty tissue that constitutes the majority of the breast envelops the mammary ducts and glands, which physiologically proliferate as a result of hormonal influences, particularly at puberty and during pregnancy. The terminal ductal lobular unit, from which the vast majority of epithelial carcinoma and carcinoma in situ arises, comprises both lactiferous ducts of variable calibers and epithelial secretory lobules. The ducts are supported by a dual layer of epithelial cells, and the lobules are composed of a luminal lining of epithelial cells and a supportive layer of myoepithelial cells. Terminal ductal lobular units are supported by variable degrees of subcutaneous fibrous and adipose tissue and undergo secretory changes under normal physiologic circumstances.

The highly specialized skin of the nipple has a papillomatous surface and numerous openings for terminal lactiferous ducts, sebaceous glands, and apocrine glands. Areolar skin demonstrates similar histology but shows occasional vellus or terminal hairs as well as prominent sebaceous gland units associated with lactiferous ducts in the dermis (i.e., Montgomery tubercles). The mammary glands connect to lactiferous ducts and produce milk-like substances and colostrum; these glands are under hormonal influences.

Numerous dermal diseases, including congenital anomalies, benign and malignant neoplasms and manifestations of various dermatoses, may involve the skin of the breast. These disorders may involve the breast solely or the breast may be involved as a result of a systemic dermatosis. In reviewing a dermatologic disorder of the breast, one useful approach is to divide these diverse entities into those primary diseases that are specific, nearly specific, or common for the skin of the breast and those secondary disorders that predominantly affect other dermatologic areas of the body but affect the breast incidentally or less commonly. The decision to classify a cutaneous disease of the breast as primary versus secondary may prove difficult and, at times, is best left unstated. Both types of dermatologic disorders may also mimic primary or secondary diseases of the breast parenchyma. For all these reasons, it is important for both the breast generalist as well as the breast specialist to be versed in these primary and secondary dermatologic disorders of the breast.

Primary Breast Dermatologic Disorders

Primary Congenital and Developmental Disorders

Amastia and Athelia

Amastia and athelia represent exquisitely rare conditions in which normal development of either breast or only nipple and areolar tissue do not occur. This does not represent an involutional phenomenon. Development of the embryologic mammary ridge (i.e., milk line), which generally extends from the bilateral axillary tails to the inguinal region, fails to occur. In the case of amastia, there is often evidence of associated ectodermal defects such as cleft palate, isolated pectoral muscle, and upper limb deformities or urologic abnormalities.

Hypoplasia and Associated Conditions

Hypoplasia (or hypomastia), defined as breast size of 200 mg (mL) or less in an adult female, represents a significant decrease in size of breast tissue relative to standard breast size adjusted for age and developmental status. Hypoplasia of mammary tissue may be unilateral or bilateral. Specifically, bilateral hypoplasia of the breast may occur in Turner (XO) syndrome and unilateral hypoplasia has been described in association with the Poland anomaly and anterior thoracic hypoplasia. Congenital mammary hypoplasia occurs in utero and has a high association with ipsilateral pectoral muscle hypoplasia. It may also occur as part of a constellation of findings in anterior thoracic hypoplasia syndrome. Acquired mammary hypoplasia may be associated with a number of conditions and comorbidities, including, but not limited to, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, anorexia nervosa, mitral valve prolapse, and tuberculosis. Unilateral or bilateral acquired hypoplasia may also be associated with high-dose irradiation to the chest and mammary structures, and degree of hypoplasia have been correlated with the dosage of irradiation. Morphea (localized scleroderma) of the chest wall in a prepubertal child may lead to deformity and hypoplasia of the breast in later years. Other congenital neural syndromes may be associated with breast hypoplasia.

Rudimentary (absent or maldeveloped) nipples may be present as an isolated congenital defect or as a component of syndromes, such as the scalp-ear-nipple (SEN) syndrome, ectodermal dysplasia complex, or Al-Awadi/Rass-Rothschild/Schinzel phocomelia syndromes. Cutaneous manifestations may include aplasia cutis congenital of the scalp, protuberant cupped or folded external ears, and sparse axillary hair; however, variable manifestations are common.

Hyperplasias, Hamartomas and Associated Conditions

Hyperplasia or macromastia refers to inappropriate and excessive growth of mammary tissue. Hyperplasia may occur in a number of settings and may be physiologic (e.g., adolescence, pregnancy), pathologic (e.g., related to neoplasia or malignancy), iatrogenic (e.g., secondary to medications), or idiopathic. Macromastia during adolescence typically occurs secondary to hormonal influences, is usually bilateral and symmetric, and can occasionally be massive (up to 10 kg per breast). The breast may show increased stromal density as a result, with variable degrees of increased dermal collagen and fibrosis. Concomitant pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia may be present and demonstrates pseudovascular spaces in a dense collagenous stroma. Hyperplasia gravidarum (gravid gigantomastia) is a rare complication of pregnancy that occurs secondary to hormonal surges and occurs most often in primigravid individuals, although it is likely to recur in subsequent pregnancies. Iatrogenic causes of hyperplasia often involves medications, such as penicillamine, indinavir, cyclosporine, and various antibiotics subclasses; however, isolated cases of palpation or manipulation macromastia have been documented. Iatrogenic causes may manifest as either unilateral or bilateral breast enlargement and medications are only marginally effective in reducing hyperplasia when attempted.

Polythelia (supernumerary nipples) ( Fig. 13.1 ) and polymastia (supernumerary breasts) develop along embryonic mammary lines, from the axillary vaults to the inguinal regions bilaterally. Specifically, polythelia represents the most common anomaly of mammary tissue in both males and females. Polythelia is present in up to 2.1% to 3.7% of individuals and greater than 90% of cases are present in the inframammary region. Accessory nipples require no treatment unless the nipple causes irritation or is excised for cosmetic reasons. Notably, vulvar lesions that previously were termed supernumerary nipples actually represent adenomas of vulvar apocrine gland derivation. Supernumerary breast tissue predominantly occurs in women and often takes the form of insignificant, gently raised, pigmented papules and most commonly is found in the left axillary and inframammary regions. Clinically they may be mistaken for acrochordon, nevi, “birthmarks,” dermatoses, or fibromas by the novice observer. Histologically, these supernumerary structures may consist of the nipple, areola, glandular tissue, or any combination of these. Microscopic sections of accessory mammary tissue are similar to those of normal mammary tissue. The epidermis may display acanthosis with undulating papillomatosis and basal layer hyperpigmentation. In the dermis, smooth muscle bundles, mammary glands, and lactiferous ducts are seen in conventional configurations.

Becker nevus (pigmented hairy epidermal nevus) represents a hamartoma of pigmented epidermis, terminal differentiated hairs and arrector pili muscles that usually occurs on the chest, shoulder, upper back, and/or upper arm. It is an androgen-dependent lesion that occurs most frequently in males in the second and third decades. It is associated with abnormalities of the underlying musculoskeletal system, including spina bifida, scoliosis, localized lipoatrophy, and hypoplasia of the pectoralis muscle, which can lead to hypoplasia or compensatory hyperplasia of the breast. The rare familial syndrome of hereditary acrolabial telangiectasia, a type of hamartoma, consists of an extensive network of superficial, thin-walled vessels and variable proliferation of vessels in the deeper soft tissues. These superficial vessels impart a bluish hue to the lips, areolas, nipples, and nail beds, which may be mistaken for cyanosis at birth. Varicose veins and migraine headaches may develop in adulthood. No serious vascular or coagulative sequelae have been reported in these cases.

Benign and malignant neoplasms, described later in this chapter, can uncommonly involve accessory or supernumerary tissues like the breast proper. In a study from Japan, benign adnexal polyps of the areola were reported to involve 4% of neonates. These small (1-mm), firm, pink papules contain hair follicles, eccrine glands, and vestigial sebaceous glands. Most wither rapidly and fall off shortly after birth.

Gynecomastia

Gynecomastia occurs in males and refers to inappropriate enlargement of the breasts. Myriad medications and exogenous substances have been associated with gynecomastia, most notably a broad range of estrogens, antiandrogens, antituberculosis medications, proton pump inhibitors, antipsychotics, antidepressants, antihypertensives, and antiretroviral therapy for patients with HIV. Approximately 40% to 50% of men with diagnosed prostate cancer develop gynecomastia as a result of treatment and hormonal dysregulation. It may occur after chemotherapy or radiation therapy for visceral malignancies or after bone marrow transplantation for hematopoietic malignancies. Traumatic gynecomastia may occur after an isolated injury to the torso or as an iatrogenic phenomenon, most notably after thoracotomy. Gynecomastia alone is not associated with an increased risk of malignant transformation. Klinefelter syndrome (XXY syndrome) is associated with the development of gynecomastia; there is a slight but significant risk of breast cancer in these patients, particularly the luminal A and B subtypes. Gynecomastia is discussed in detail in Chapter 7 .

The histologic appearance of gynecomastia transitions from an early active phase into an inactive quiescent phase during the traditional chronology of this disorder. In the active phase, there is ductal proliferation and hyperplasia of stromal parenchyma accompanied by a periductal or diffuse mixed lymphoplasmacytic and mononuclear infiltrate. The ducts may develop papillary and cribriform patterns with a prominent myoepithelial layer. As the lesion develops, the inactive phase is attained; this phase is characterized by ductal epithelial atrophy and stromal fibrosis.

Primary Inflammatory Disorders

Dermatoses of the Nipple and Breast

Eczematous Dermatitis (Nummular Eczema).

Eczematous dermatitis (nummular eczema or eczema) ( Fig. 13.2 ) of the nipple clinically presents as ill-defined, erythematous, scaly patches or plaques that may demonstrate total and partial lichenification or excoriation due to associated irritation and pruritus. Bilateral involvement is common. Eczema of the breast or nipple may present as erythema, scale, crusting, fissures, vesicles, erosions, or lichenification. Nummular eczema may also present as single or multiple erythematous, slightly raised plaques with fine to moderate scale, slight oozing, and extreme pruritus. Involvement of the nipple may mimic Paget’s disease, squamous cell carcinoma in situ (i.e., Bowen disease), and myriad inflammatory or infectious etiologies. Nipple eczema is the most common presentation of atopic dermatitis of the breast and has been considered a minor criterion in the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis. At present, it is not included in the diagnostic major criteria for atopic dermatitis ; however, it represents an important diagnostic feature, particularly during prepubertal years and periods of breastfeeding. All of these disorders typically present as a scaly erythematous, often pruritic nipple-areola complex ( Box 13.1 ). Eczematous involvement localized to a mastectomy scar may also raise suspicion of breast carcinoma recurrence.

Inflammatory Dermatoses

Seborrheic dermatitis

Psoriasis

Pityriasis rosea

Chronic contact dermatitis

Discoid lupus erythematosus

Darier disease

Nummular eczema

Nipple eczema

Jogger’s nipples

Infections

Erythrasma

Tinea corporis

Tinea versicolor

Neoplasms

Lichen planus–like keratosis

Actinic keratosis

Superficial basal cell carcinoma

Bowen disease

Paget’s disease

Mycosis fungoides

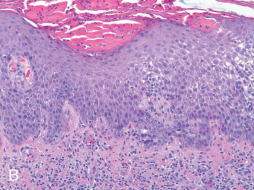

A biopsy specimen of eczema typically shows spongiotic dermatitis with a mixed dermal perivascular and/or interstitial inflammatory infiltrates composed of variable proportions of lymphocytes and histiocytes with occasional eosinophils and neutrophils (see Fig. 13.2B ). During an acute flare, the predominant histologic finding is spongiosis that may coalesce to produce microvesicles, vesicles or bullae. Neutrophilic microabscesses in the stratum corneum and focal parakeratosis, along with serum and scale crust, can be observed as lesions become irritated and/or impetiginized. As the lesion progresses, the degree of spongiosis and inflammation recedes and epidermal hyperplasia becomes more prominent, manifesting as either regular psoriasiform hyperplasia or changes consistent with lichen simplex chronicus. Chronic lesions may demonstrate persistent mild patchy lymphocytic inflammation in addition to changes such as dermal fibrosis, pigment incontinence and/or epidermal atrophy. The differential diagnosis includes allergic contact dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis, lichen simplex chronicus, infection with Candida spp. and Paget’s disease. Nummular eczema may be difficult to distinguish from chronic allergic contact dermatitis; patch testing may prove helpful in identification of an offending allergen. Finally, Sarcoptes scabiei mites can directly infest the nipple, areola, and inframammary creases to produce characteristic linear lesions produced by mite burrows. Patients present with extreme pruritus and excoriation secondary to the presence of the mites and/or scybala in the stratum corneum. Manual unroofing of burrow sites during clinical visits allow for scrapings to be produced for microscopy, which will reveal the organism, its eggs, and/or feces. Topical scabicides typically eradicate the mites after multiple applications.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis.

Allergic contact dermatitis ( Fig. 13.3 ) is a less common type of dermatitis but should be considered in all cases with appropriate signs and symptoms. Contact dermatitis in the area of the breast and nipple most often results from nickel allergy, and the lesions appear under bra straps and hooks in the shape of the offending metal part. Other common causes of contact dermatitis include topical medications, perfumes, latex, and airborne allergens. Contact dermatitis to lanolin, beeswax emollients, chamomile ointments, and nail polish has been reported. A careful history of environmental exposures and the use of patch testing usually identifies an offending agent or collection of agents. Histologic examination characteristically shows spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (see Fig. 13.3 ). Flask-shaped collections of Langerhans cells, which often open up onto the skin surface, are common findings. Changes resulting from chronic irritation (i.e., lichen simplex chronicus) may also be present histologically if the exposure is long-standing.

Irritant Contact Dermatitis.

Irritant contact dermatitis of the nipple (e.g., jogger’s nipple, runner’s nipple) or breast develops most commonly in physically active adults and occurs secondary to friction with clothing. Treatment of irritant contact dermatitis is tailored to cause and generally consists of gentle cleansers, moisturizers, and topical corticosteroids as needed for symptomatic relief. Relief may also be achieved by wearing soft, nonabrasive clothing or applying adhesive tape to protect the nipples. Topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used for maintenance therapy in difficult cases. Identification and subsequent avoidance of the triggering factor is the treatment of choice. The most important clinical and diagnostic issue with respect to nipple dermatitis is discerning this benign reactive entity from Paget’s disease of the nipple. If a case of suspected nipple dermatitis does not resolve with topical therapy, the diagnosis of Paget’s disease should be more seriously entertained. A biopsy may prove necessary for definitive diagnosis in these cases. Histologic features include eosinophilic spongiotic dermatitis with or without a superficial dermal inflammatory infiltrate. Flask-shaped collections of Langerhans cells, which often open up onto the skin surface, are common findings. Abnormal findings, such as nests of melanocytes or malignant epithelial cells, Pagetoid spread of atypical cells, full-thickness epithelial atypia, or tumor formation, are invariably absent.

Dermatoses and Inflammatory Conditions Involving the Dermis

A wide range of reactive and inflammatory conditions can involve the dermal mammary tissue. Their importance cannot be understated not only because of their capacity to cause concern and discomfort for patients but also their ability to simulate neoplastic and malignant conditions on clinical examination and radiography. Benign conditions account for the majority of breast biopsies in the United States, with reactive and inflammatory conditions representing the majority of these nonneoplastic biopsy specimens. An understanding of these reactive and inflammatory conditions will aid in avoiding misdiagnosis and preventing unnecessary treatment.

Mammary Duct Ectasia.

Duct ectasia may occasionally be identified in skin biopsies and consists of superficial lactiferous ducts in mammary tissue. Currently, it is hypothesized that duct ectasia results from obstruction of ducts with secondary inflammatory reaction to the stagnant contents. Superimposed changes consistent with ductal rupture are often concomitantly present. Histologically, there is ectasia of medium- to large-sized lactiferous ducts with accumulation of amphophilic secretory material and macrophages in the lumen and fibroelastic thickening of the duct wall. External concentric fibrosis may be seen in subacute or chronic lesions, and eccentric fibrosis, epithelial denudation, and/or fibrous obliteration of the duct may highlight an area of previous rupture and repair. A particularly helpful histologic feature may include the presence of cholesterol crystals in the periductal infiltrate. Mammary duct ectasia can be found in association with fibrocystic diseases; however, these two entities are not thought to be pathogenetically related.

Radiation Dermatitis.

Multiple manifestations of radiation dermatitis can involve the skin of the breast. The first and most common type is erythema with fine scales that develops during the course of radiotherapy. The patient is typically uncomfortable, but the course is self-limited and generally can be managed with soothing topical treatments; however, in some cases, scarring, atrophy, telangiectasia, and scaling may become superimposed on prior sites affected by radiation therapy. This form of radiodermatitis is rare but chronic and may progress to tissue necrosis, ulceration, and de novo cutaneous malignancies (most commonly squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma). Patients with a clinical history of prior radiation therapy may develop radiation recall dermatitis when exposed to subsequent chemotherapy agents. Radiation recall dermatitis often presents as a painful, erythematous maculopapular rash directly overlying or in close approximation to a previous site of irradiation. Vitiligo has also been reported after radiotherapy as well.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a congenital state where the apocrine glands do not undergo normal apoptosis and histologically shows a florid mixed inflammatory infiltrate extending deep into dermal tissue usually predominates. In active lesions, collections of abscesses are noted, along with follicular plugging and sinus tract formation. During the course of healing and wound contraction, granulation tissue, broken hair shafts, keratin debris, and ensuing foreign-body giant cell reaction may be evident. Chronic lesions commonly demonstrate extensive scarring and fibrosis along with eradication of normal adnexal structures.

Subareolar Abscess.

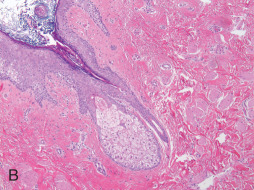

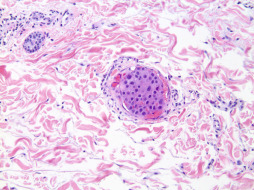

Repeated or chronic abscess formation ( Fig. 13.4 ) in the subareolar region results in squamous metaplasia of the terminal ends of lactiferous ducts, further sequestering and propagating abscess pockets. The clinical presentation and treatment is discussed in detail in Chapter 6 .

Ruptured Epidermal Inclusion Cyst.

A ruptured epidermal inclusion cyst can be characterized by intense inflammation and abscess formation, most commonly in subareolar tissue. A ruptured cyst can mimic the superficial appearance of infiltrative carcinomas on physical examination.

Dermatoses and Inflammatory Conditions Involving the Subcutaneous Tissue

Fat Necrosis.

Fat necrosis presenting as a palpable mass may raise serious concern for clinicians and patients alike. Clinically significant fat necrosis arising in superficial subcutaneous tissue is most commonly secondary to trauma ( Fig. 13.5 ). Fat necrosis is a benign nonsuppurative inflammatory disease of adipose tissue that was initially described in the breast in 1920. It is a sterile process resulting from aseptic saponification of fat by means of blood and tissue lipase. The incidence is estimated to be 0.6% in the breast, representing up to 2.75% of all benign lesions. It is found incidentally accompanying 0.8% of breast tumors and 1% of cases of surgical breast reduction. The average age of patients at presentation is 50 years. Causes are variable and include trauma, radiotherapy, anticoagulation therapy (e.g., warfarin administration), cyst aspiration, biopsy, lumpectomy, reduction mammoplasty, implant removal, breast reconstruction with tissue transfer, duct ectasia, and breast infection. Less common causes include polyarteritis nodosa and granulomatous angiopanniculitis. In a significant number of patients, the cause is designated as idiopathic.

Fat necrosis can present as a mass on palpation and either as a hyper- or hypoechoic area on ultrasound imaging. Clinically, therefore, it can mimic the appearance of invasive carcinoma. It is obviously important to distinguish fat necrosis from invasive carcinoma, and thus biopsy may be warranted. Core biopsy of breast lesions has been shown to be more sensitive than fine-needle aspiration. Ironically, one of the side effects of biopsy is iatrogenic fat necrosis, which contributes to an additional enlarging mass. Unfortunately, some patients experience biopsy after biopsy only to reveal a diagnosis of ongoing or recrudescent fat necrosis.

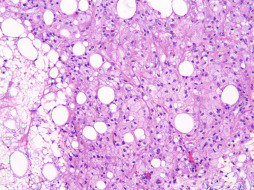

Fat necrosis is recognized histologically by lipid-engorged macrophages and foreign-body giant cells surrounded by an interstitial inflammatory infiltrate composed of plasma cells and lymphocytes. Apoptosis and necrosis prevail in adipose lobules. Healing occurs by fibrosis, which begins at the periphery of the cyst-like areas. Depending on the degree of fibrosis, these areas are either replaced completely by fibrous tissue or remain as cavities. Calcification may occur in the area of fibrosis and represents a relatively late finding. Clinical presentations range from an incidental benign lesion to a mass lesion. In most instances, fat necrosis is clinically occult; however, it may present as a single or multiple smooth, round, firm nodules or irregular masses and can also be associated with overlying cutaneous ecchymosis, erythema, inflammation, pain, retraction or thickening, nipple retraction, and lymphadenopathy.

Panniculitis.

Panniculitis (inflammation of the subcutaneous tissue) may be encountered in the breast secondary to many different causes. Autoimmune phenomena may uncommonly produce lobular panniculitides, such as lupus profundus in patients with established or evolving systemic lupus erythematosus. Ruptured or bleeding breast implants may cause extensive or generalized panniculitis that may extend beyond the confines of the breast, an important clinical sign. Silicone granulomas appear as painful, irregularly shaped lumps or plaques in patients who have received injections of free silicone or whose silicone implants have ruptured. Microscopic examination of this tissue shows a characteristic “Swiss cheese” granulomatous inflammatory pattern where the silicone has dissolved from multinucleated giant cells and extracellular areas during histologic processing.

Factitial panniculitis may arise from mechanical injury to the breast or from repetitive attempts at self-injurious behavior by the patient. Possible presentations may mimic virtually any dermatosis and include excoriation, ulceration, puncture wounds and embedded foreign bodies, eczema, vesiculobullous lesions, and nipple discharge. Factitial disease should be considered when an unusual pattern or presentation is not consistent with established clinicopathologic entities or when the patient exhibits an unusual or strange affect or response to the problem. Careful clinical evaluation with mammography and biopsy, if necessary, should be taken to rule out primary organic disease of the breast. Documented practices that may unfortunately result in panniculitis include acupuncture and cupping. Psychiatric evaluation is recommended in cases of suspected self-injurious factitious panniculitis.

Mastitis.

Mastitis is defined as inflammation of the breast, irrespective of cause, and can be infectious or noninfectious in origin ( Fig. 13.6 ). The incidence of mastitis is approximately 10% in mothers by 3 months postpartum. Reported rates range from 2% to 33%, and the condition can occur in nonlactating patients. Abscesses occur in about 3% of women who experience breast inflammation and are more likely to occur within the first 6 weeks postpartum. A prevalence of 23% has been reported for Candida albicans colonization at 2 weeks postpartum, but not all of these women develop an infection. Ductal infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus and mixed flora have been documented.

Noninfectious mastitis may occur and should be considered as “milk stasis” secondary to ineffective or obstructed milk removal. When breast milk is obstructed, the paracellular pathways open, resulting in increased levels of sodium and chloride, decreased levels of lactose and potassium, and leakage of inflammatory cytokines, which can provoke fever, chills, and muscle aches, clinically mimicking an infectious process. Mastitis can present with no significant redness, fever, or systemic symptoms; however, it may manifest in such a severe fashion to necessitate hospitalization and intravenous antibiotic therapy.

Infectious mastitis is most frequently caused by S. aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci. Another known cause is streptococci, which should be suspected whenever bilateral mastitis presents early in the postpartum period. Other causes include Bacteroides spp., Escherichia coli , Peptostreptococcus spp., Moraxella spp., Eikenella spp., Mycobacterium tuberculosis (rare), and Candida spp. (rare). In the case of infectious mastitis, especially candidal mastitis during breastfeeding, both mother and infant need to be treated simultaneously. Infectious mastitis typically presents with a fever greater than 38.5°C, flulike symptoms, and a wedge-shaped area of localized tenderness. Treatment is focused on reversing milk stasis, maintaining milk supply, and continuing breastfeeding, along with providing maternal comfort. Patients with acute pain, severe symptoms, systemic symptoms, and/or fever need prompt medical attention with the appropriate antibiotics and incision and drainage of an abscess.

Special diagnostic subtypes of mastitis exist, all of which may involve an infectious, inflammatory and/or retention etiology: plasma cell mastitis, puerperal/lactational mastitis, lymphocytic mastitis, granulomatous lobular mastitis, and foreign-body mastitis.

Plasma Cell Mastitis.

Microscopic sections of lesions demonstrate a florid periductal mastitis characterized by an impressive plasma cell reaction to retained ductal secretions. Key features for diagnosis include ductal epithelial hyperplasia accompanied by an associated intense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. Xanthomatous features can often be observed as lymphocytes and plasma cells surround zones of histiocytes engulfing disrupted ductal material. Neutrophils and periductal fibrosis are uncommonly observed.

Puerperal/Lactational Mastitis.

The histologic appearance is dependent on the nature and chronicity of these lesions. Acute involvement typically shows neutrophilic influx along with focal necrosis, whereas chronic lesions often display organized abscess formation with variable degrees of fibrosis and secondary fistula formation.

Lymphocytic Mastitis.

This entity is also referred to as sclerosing lymphocytic lobulitis, which characterizes the histologic appearance. There are circumscribed aggregates of lymphocytes within and surrounding terminal ducts and lobules associated with surrounding stromal fibrosis. Perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and germinal centers are also noted. Diabetic mastopathy shares certain clinical and pathologic features.

Granulomatous Lobular Mastitis.

This form of mastitis represents a notable mimic of benign or malignant neoplasia in breast lesions, typically in women of young to middle age. A significant number of cases are associated with parity or oral contraceptive pills; however, many cases have no well-defined causes and are designated as idiopathic. It is characterized histologically by multiple necrotizing granulomata and/or abscesses located in association with or in approximation to segmental and subsegmental lactiferous ducts in a lobulocentric pattern. Acid fast and/or Gomori methenamine silver stains may be needed to exclude mycobacterial and fungal infections.

Foreign-Body Mastitis.

Paraffin or silicon injections for cosmetic purposes may uncommon induce a prominent foreign-body giant cell reaction with a characteristic histologic appearance. The exogenous deposits are often dissolved during tissue processing, subsequently revealing a residual interstitial vacuolar (“Swiss cheese”) appearance to the biopsy specimen. Microscopic examination reveals characteristic vacuoles of variable size surrounded by macrophages and foreign-body giant cells. When the reaction is severe, cutaneous ulceration, capsule formation, and sinus tracts may develop. The same histopathology can be produced by ruptured or leaking silicone breast implants, as previously described. Breast implants are discussed in Chapter 33 .

Disorders of Keratinization

Reactive changes involving epidermal keratinization (e.g., hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis) are secondarily discussed in other sections on inflammatory and reactive dermatoses, where appropriate.

Axillary Granular Parakeratosis.

Axillary granular parakeratosis is an acquired disorder of keratinization, originally detailed by Northcutt and colleagues in 1991, which typically presents as a bilateral pruritic cutaneous eruption involving flexural regions. It occurs most commonly in the axillae and may extend to the skin of the axillary tail and upper outer quadrants of the breasts; however, lesions may occur in any body flexure, including the inframammary folds. The lesions typically appear as hyperpigmented red or brown papules that coalesce over time into dark to violaceous plaques covered by an adherent keratotic scale. The astute clinician may be able to accurately diagnose this disorder in prototypical cases, although the findings may be nonspecific and can mimic a number of inflammatory and neoplastic diseases. The clinical differential diagnosis includes seborrheic dermatitis, lichen planus, acanthosis nigricans, and genodermatoses, such as Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. Distinctive features are present on histopathologic examination: broad compact parakeratosis, hyperkeratosis with hypergranulosis that involves the stratum corneum, vascular proliferation in the superficial dermis, and variable degrees of acanthosis and papillomatosis. Inflammation is usually mild, if present, unless there is secondary traumatization or excoriation. The pathogenesis of these lesions is currently believed to be due to inhibition of conversion of profilaggrin to filaggrin in the skin, which leads to disruption of maturation in the stratum corneum. Processing and trafficking of keratohyalin granules is affected and leads to retention of granules in the stratum corneum, producing its characteristic histologic appearance. This is reinforced by the demonstration of an absence of filaggrin in keratinocytes from patients with axillary granular parakeratosis. The majority of cases are seen in middle-aged women, although cases have been documented in children and men. There is no obvious racial predilection. Lesions are most commonly associated with mechanical forces (e.g., friction, perspiration, humidity, follicular occlusion), introduction of new medications, and chemical components of antiperspirants and deodorants, but myriad causes have been proposed. A significant number of cases are self-resolving within weeks to months after the initial presentation; however, some cases may cause significant discomfort and/or are esthetically displeasing to the patient. Topical or oral retinoids, especially isotretinoin, and topical steroids have shown excellent results in patients with chronic or recurrent disease. Other treatments include keratolytics, topical vitamin D analogs, and cryotherapy.

Primary Neoplastic Disorders

Primary Benign Neoplastic Disorders

Seborrheic Keratosis.

Seborrheic keratoses are the most common epithelial neoplasms of the breast. Grossly, the lesions are typically flat-topped or irregular waxy papules and small plaques that sit on the surface of the skin. Occasional lesions may be mounded, polypoid, or pedunculated. They are generally brown or black in color; however, they may present as flesh-colored or erythematous lesions de novo or secondarily as a result of irritation. Bleeding and crusting are not uncommon, usually as a result of excoriation, trauma due to rubbing on clothing or other garments, mechanical removal, or, uncommonly, autoamputation. Patients may present with solitary seborrheic keratosis, but it is extremely common to present with multiple synchronous or metachronous lesions. The Leser-Trélat sign refers to a paraneoplastic phenomenon in which there is an abrupt eruption of numerous seborrheic keratoses in patients with visceral malignancies and is related to high levels of circulating epidermal growth factor receptor. Uncommonly, this sign has heralded the diagnosis of an occult malignancy, including carcinoma of the breast. Although many histologic variants of seborrheic keratosis have been described, all subtypes exhibit hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis, pseudohorn cysts, and variable inflammation. These lesions are uniformly benign. Treatment is generally reserved for symptomatic lesions or for cosmetic reasons, which consists of excision, curettage, cryotherapy, or ablation.

Lichen Planus–Like Keratosis.

Lichen planus–like keratoses, also referred to as benign lichenoid keratoses, are solitary (rarely multiple) 5- to 20-mm, bright red, violaceous or brown plaques on the chest and upper back. Clinically, they can mimic lentigo simplex and other pigmented lesions, superficial basal cell carcinoma, or squamous cell carcinoma in situ. The histologic features mimic those of lichen planus. Lesions typically demonstrate hyperkeratosis, serrated acanthosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis and a dense bandlike lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate abutting the dermal-epidermal interface. Lichen planus–like keratosis typically demonstrates parakeratosis and the presence of increased eosinophils in the inflammatory infiltrate. These features, along with clinical history and presentation, help to distinguish these benign lesions from traditional lichen planus.

Benign Cysts and Adnexal Tumors.

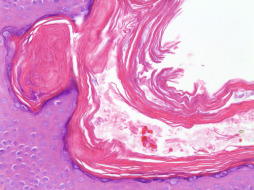

Adnexal tumors of pilosebaceous origin that occur on the breast are predominantly cystic and include epidermal inclusion cysts, trichilemmal cysts (pilar cyst), vellus hair cysts, and steatocystomas. Epidermal inclusion cysts are common smooth dome-shaped lesions with an overlying pinpoint punctum that are fluctuant on palpation. These lesions may enlarge and either become inflamed and/or rupture, which often brings them to clinical attention. Histologic examination reveals a unilocular cystic structure lined by keratinizing squamous epithelium with a conspicuous granular layer and filled with lamellated keratin debris. Ruptured cysts are denoted histologically by granulomatous inflammation with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and multinucleated histiocytes, some of which may contain phagocytosed keratin.

Trichilemmal cysts (pilar cysts) typically present as smooth dome-shaped lesions without an overlying punctum and are notably firm (“rock-like”) on palpation. Histology shows a cystic nodule lined by keratinizing squamous epithelium without a granular layer and containing densely packed lamellated keratin with or without calcification. Because of their composition, they are easily shelled out by surgical means.

Vellus hair cysts are asymptomatic 1- to 2-mm follicular papules that typically appear in late childhood or early adulthood and may be associated with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Histologic examination reveals a cyst lined by keratinizing squamous epithelium and containing lamellated keratin and one to many small, vellus hair shafts. Rupture with accompanying granulomatous inflammation is not uncommon. Steatocystomas are small, solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple (steatocystoma multiplex), 1- to 5-mm yellowish papules containing a creamy or oily fluid upon expression. These cysts are lined by thin, stratified squamous epithelium with a prominent homogeneous, eosinophilic, crenulated cuticle that mimics a sebaceous duct. Attenuated sebaceous lobules may be seen in contiguity with the epithelial lining. The cysts usually appear empty on histology because the contents dissolve during processing. Steatocystoma multiplex ( Fig. 13.7 ) is an autosomal dominant inherited, or uncommonly, sporadic disorder which presents as multiple asymptomatic cysts on the trunk and proximal extremities. Steatocystoma simplex is a sporadic condition that begins in adolescence or young adulthood and affects both sexes equally. This condition has been associated with pachyonychia, acrokeratosis verruciformis, hypertrophic lichen planus, hypohidrosis, hidradenitis suppurativa and natal teeth. A relationship between steatocystomas and vellus hair cysts has been reported, and some hypothesize that eruptive vellus hair cysts and steatocystomas represents variants of the same pathogenetic disease. Hybrid lesions with histologic features of both cyst types have been described. Steatocystoma multiplex express keratins 10 and 17 in contrast to eruptive vellus hair cysts, which express only keratin 17. Treatment usually is not required for these benign conditions; however, treatment may be attempted for inflammatory lesions and may include oral tetracycline antibiotics. Isotretinoin therapy also has been shown to be effective in some patients. Cosmetic treatment may be sought for persistent or enlarging lesions. Surgical treatment may include aspiration, extirpation, surgical excision, or laser destruction. Carcinoma may arise from the epidermal portions of these cysts in rare cases.

Adnexal tumors of eccrine and apocrine origin commonly occur on the breast. Given that the mammary gland is a modified sweat gland. Common benign adnexal tumors involving the breast include, but are not limited to, poromas (tumors arising from or differentiating as the intraepithelial portion of the eccrine duct), hidradenomas (tumors of the straight portion of the eccrine duct), spiradenomas, and cylindromas (tumors of the deep coiled eccrine gland).

Poromas appear clinically as raised or polypoid flesh-colored lesions that may ulcerate and, as a result, are often mistaken for pyogenic granulomas. Histologic examination shows a proliferation of broad, anastomosing bands of small, cuboidal cells containing small caliber duct-like spaces beneath a flattened epidermis. The intervening stroma is characteristically edematous and richly vascular. The absence of peripheral palisading is an important distinguishing histologic feature from basal cell carcinoma.

Hidradenomas are primarily intradermal tumors, 0.5 to 2 cm in diameter, with intact overlying skin. Microscopically, well-circumscribed, sometimes encapsulated lobules of polygonal and cuboidal cells within which simple tubular ducts are embedded are present in the dermis. The polygonal cells have round nuclei with basophilic cytoplasm and indistinct cell borders. The cuboidal cells have clear or pale cytoplasm; when clear cells are numerous, the tumor is termed clear cell hidradenoma .

Spiradenomas and cylindromas present as solitary, markedly tender, dermal or subcutaneous masses without epidermal connection. Microscopic examination reveals a spectrum of deeply basophilic, sharply demarcated lobules containing variable admixtures of two types of epithelial cells. One cell type consists of cells with relatively large, centrally placed clear nuclei and scant cytoplasm that forms ductular structures, whereas the second cell type consists of cells with small dark nuclei and wispy basophilic cytoplasm found primarily at the periphery of the lobules. Reduplicated basement membrane material, appearing as homogeneous, dull, eosinophilic masses, is also present within and/or surrounding the tumor in hidradenomas, spiradenomas, and cylindromas. Lymphocytes are present in lobules of spiradenomas more commonly than in cylindromas. Mitoses may be present in all cutaneous tumors and, unless atypical in appearance, should not be taken as a sign of malignancy unless other concerning morphologic features are observed. Unless frank carcinoma or lymphovascular or perineural invasion arises in an adnexal neoplasm, histologic features alone may not predict the clinical behavior of individual neoplasm. Consequently, excision of benign adnexal tumors is the currently recommended management. Benign neoplasms of sebaceous gland origin that occur as primary dermatologic neoplasms must be distinguished from invasive breast carcinoma, which may involve the skin of the breast. Adenomas of sebaceous glands consist of well-differentiated sebaceous lobules containing cells with prototypical multivacuolated cytoplasm and small basophilic nuclei.

Syringomatous adenoma of the nipple (syringomatous tumor) represents an uncommon neoplasm of sweat gland derivation that bears a histologic resemblance to conventional cutaneous syringoma. It is found predominantly in adult females with the greatest incidence in the fourth and fifth decades and usually presents as a unilateral firm erythematous or flesh-colored lesion. An unusual report of syringomatous adenoma arising in a supernumerary breast has been reported. This is a benign but locally infiltrative lesion typically located in the dermis and/or subcutis subjacent to the nipple or areola. Ulceration is uncommon because these are typically seated deeply in the skin. Gross examination upon sectioning may reveal multiple small cysts in the dermis or subcutis. Histologically, round or irregular open tubules that have been likened to commas or teardrop figures extend in an infiltrative growth pattern to involve dermal collagen, subcutaneous fat, or smooth muscle. Tubular lumens may contain amphophilic or eosinophilic secretions or, uncommonly, keratinous debris. The superjacent epidermis is typically acanthotic. Variable amounts of squamous and apocrine differentiation are usually present and do not affect the diagnosis or prognosis of this entity. Perineural invasion is not uncommon and does not indicate malignant behavior. Myoepithelial cells are invariably present around the tubules (although these cells may be inconspicuous without immunohistochemistry), differentiating this lesion from invasive carcinoma. Cytologic atypia and necrosis are minimal. Of note, this lesion was once believed to be a superficially located variant of low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma of the breast, although this diagnosis has lost favor. Metastasis has not been reported in association with these lesions. Complete excision is the recommended management of this lesions.

Erosive Adenomatosis of the Nipple.

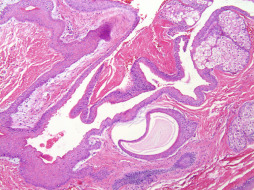

Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple (nipple adenoma, florid papillomatosis of the nipple) ( Fig. 13.8 ) is a rare, benign neoplasm of lactiferous ductal epithelium. The peak incidence is in the fifth to seventh decades. This condition usually presents clinically with a unilateral erythematous crusting or oozing lesion with induration of the nipple that may be accompanied by ulceration. A subareolar mass may be present in a significant number of cases, which may provide the impetus for clinical attention. Clinically, this lesion can be mistaken for Paget’s disease, nipple eczema, or carcinoma. On histologic examination, two patterns of growth are evident. The first pattern, associated with erosive lesions, is adenomatous, a proliferation of round, oval, or irregularly shaped ducts lined by cuboidal to columnar epithelium with an outer myoepithelial layer and embedded in a fibrovascular or centrally hyalinized stroma. The second pattern, associated with a mass effect, is papillomatous-papillary–type hyperplasia of columnar epithelial cells lining the ducts resulting in tufting intraluminal projections without fibrovascular cores. These papillomatous regions may demonstrate distortion and crowding. Occasional mitotic figures and focal necrosis may be present; however, these features in isolation are not indicative of malignancy. Squamous metaplasia may present focally. In both patterns, the superjacent epidermis is acanthotic. Numerous plasma cells may be seen in the dermis. Histologically, nipple adenomas may be mistaken for invasive ductal carcinoma or ductal carcinoma in situ. Important differences from invasive carcinoma and ductal carcinoma in situ include absence of significant cytologic atypia and absence of atypical mitotic figures. Myoepithelial cells are ubiquitously present and true cribriform proliferations are not seen in nipple adenomas. Cases of nipple adenoma with synchronous and metachronous carcinomas have been reported. Additionally, malignant transformation of a nipple adenoma has rarely occurred, and noncontiguous invasive mammary carcinoma has secondarily involved nipple adenomas of the breast in exceptionally rare cases. Excisional biopsy is most helpful in establishing the diagnosis. Although the morphologic features of this lesion may concern the novice observer, knowledge of this lesion and its typical histologic appearance and configuration will help prevent misdiagnosis of a malignant neoplasm. Complete excision is recommended.

Primary Malignant and Neoplastic Disorders

Paget’s Disease of the Breast.

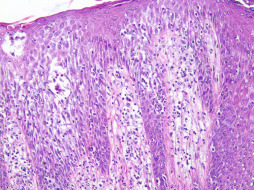

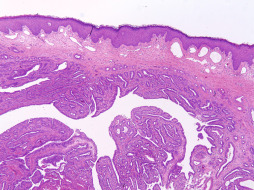

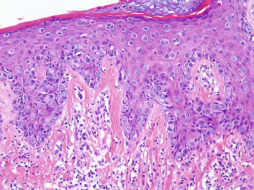

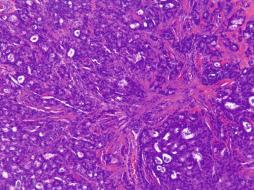

Paget’s disease of the nipple ( Fig. 13.9 ) represents a malignant neoplasm that is defined pathologically as an intraepidermal carcinoma. Although Paget’s disease can occur anywhere along the milk line, the disease is most commonly localized to the breast and therefore it is included here as a primary breast neoplasm. Paget’s disease was first described in 1856 by Velpeau and the concept was later refined by Sir James Paget in 1874 as a syndrome in which ulceration of the nipple was associated with an underlying carcinoma. Paget’s disease of the breast is an uncommon neoplasm, accounting for 1% to 3% of all breast tumors. This disease occurs predominantly in women, although cases in men do occur and are associated with a worse prognosis. Clinically, it presents as eczema, erythema, weeping, ulceration, bleeding, and/or itching of the nipple or areola depending on the chronicity of the lesion. Nipple discharge is not infrequent. The eczematous reaction most often appears initially on the nipple and then subsequently spreads centrifugally toward the areola. In advanced cases, the carcinoma can extend to the periareolar skin. The diagnosis of Paget’s disease can be easily confused with reactive or inflammatory dermatoses and is often delayed for months before a correct diagnosis is rendered.

Currently, the most widely accepted theory (i.e., epidermotropic theory) regarding the pathogenesis of Paget’s disease theorizes that Paget’s cells are ductal carcinoma cells that have migrated from the underlying mammary ducts or lobules of the terminal ductal lobular unit to the epidermis. This theory is strongly supported by the presence of concomitant invasive mammary carcinoma or carcinoma in situ in the vast majority of cases, ranging from 92% to 100% of cases. The underlying carcinoma or carcinoma in situ can be located in any quadrant of the breast and can demonstrate either ductal or lobular morphology. Interestingly, one report found that 45% of palpable invasive carcinomas associated with Paget’s disease were located in the upper outer quadrant of the breast ; however, this predilection has not been consistently reproduced. The underlying neoplasm associated with cases of Paget’s disease is multifocal or multicentric in 32% to 63% of cases. This potential for multicentricity renders it crucial to evaluate the entire breast, even if a solitary lesion is noted on physical examination (particularly solitary subareolar masses). Invasive carcinoma may also be clinically occult in a significant number of cases, with Paget’s disease heralding its presence. The exceptionally rare diagnosis of invasive mammary Paget’s disease involving dermal tissue without definitive evidence of a concomitant invasive ductal or lobular mammary carcinoma is rendered as a diagnosis of exclusion and is of great academic interest.

Paget’s disease is characterized histologically by the infiltration of the epidermis with enlarged round and ovoid tumor cells with abundant pale amphophilic cytoplasm and pleomorphic vesicular nuclei. The tumor cells are often arranged in a “buckshot” pattern throughout the epidermis, with individual cells present at all layers. Cytologic atypia is present, including pleomorphism and mitotic figures. Paget’s cells show similar immunohistochemical staining pattern as that of conventional mammary carcinomas, with overexpression with low molecular weight cytokeratins (CKs), such as CK7. High molecular weight CKs and CK20 are typically negative. Paget’s cells typically express other antigens, such as epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (GCDFP-15), and mucicarmine, reinforcing the glandular origin of these cells. Paget’s cells also typically overexpress p53 and HER2 and exhibit an increased proliferative rate with ki67 (MIB-1). Studies have demonstrated that the HER2 oncoprotein may function in vivo to promote intraepithelial spread of adenocarcinoma cells. Invasive carcinoma associated with Paget’s disease more commonly exhibits negative estrogen and progesterone receptor immunoreactivity due to the preponderance of underlying carcinomas that possess a higher pathologic grade. The RAS oncogene product p21 and c-erbB-2 demonstrate overexpression, and these findings are associated with aggressive disease and with worse prognosis.

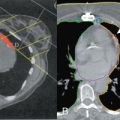

Diagnosis is accomplished by histologic examination of lesional tissue, although contemporary imaging modalities (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound, or radiographic mammography) continue to prove useful in triaging and characterizing these lesions. Specifically, in cases of noninvasive breast cancer, magnetic resonance imaging has a sensitivity of 95% compared with a value of 70% for mammography. This sensitivity is amplified in cases in which physical examination and mammography are unremarkable. Breast conserving surgery combined with irradiation therapy for patients with invasive and in situ mammary carcinoma has become the treatment of choice in many instances. Surgical procedures should immutably include the entire nipple-areolar complex. Treatment with breast conserving surgery has demonstrated similar long-term survival rates to those of modified or radical mastectomy. Sentinel lymph node biopsy should be considered to evaluate the axillary lymph nodes in all patients with Paget’s disease, although the prognostic utility of categorical sentinel lymph node evaluation is debatable among providers. Prognosis depends largely on the presence and grade of an underlying carcinoma or carcinoma in situ. Paget’s disease and its significance outside of its dermatologic manifestations and pathology are discussed extensively in Chapter 12 .

Paget’s disease without evidence of underlying invasive or in situ mammary carcinoma most commonly occurs in cases of occult or undetected concomitant disease; however, cases may certainly present in which Paget’s disease appears to exist in isolation after an extensive initial battery of clinical, radiologic, and pathologic testing. In the uncommon event that Paget’s disease of the breast presents without an initially identifiable underlying invasive or in situ carcinoma component, a more dedicated clinical, radiologic, and pathologic assessment would be prudent. Secondary modalities, such as breast magnetic resonance imaging and fine-needle aspiration, can prove useful. Currently, recommended management for patients with biopsy-proven Paget’s disease and without clinical, radiologic, and pathologic evidence of invasive or in situ mammary carcinoma is excision of the nipple-areolar complex and circumferential periareolar skin with conservative clinical follow-up. If invasive carcinoma is subsequently found, sentinel lymph node evaluation and adjuvant therapy can be undertaken at the discretion of the clinician in addition to conventional surgical management. The utility of sentinel lymph node sampling in patients with confirmed Paget’s disease and compelling lack of evidence for an invasive carcinoma has been debated, although it is not required for evaluation in these patients at this time.

Inflammatory Breast Carcinoma.

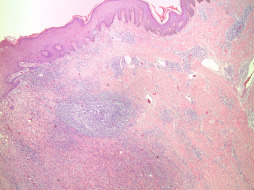

Inflammatory breast carcinoma ( Fig. 13.10 ) represents a primary breast dermatologic malignancy that prototypically presents as diffusely red, warm, slightly indurated, and tender skin overlying at least one-third of the overall surface area of the breast. The clinical manifestations noted are required for diagnosis and appropriate categorization, including American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor staging. Histologic sections demonstrate diffuse occlusion or obstruction of dermal and/or subcutaneous lymphatic and vascular channels by tumor emboli, which are cytologically atypical and often similar in appearance to the primary mammary carcinoma. Vascular congestion and tissue edema accompany the presence of lymphovascular tumor emboli. Recurrent metastatic carcinoma, most often found in mastectomy scars, may also manifest as florid lymphovascular tumor embolization (i.e., secondary inflammatory breast carcinoma). Because of the diagnostic and prognostic importance of this condition, it is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 64 .

Atypical Vascular Lesion.

After radiation therapy for breast cancer, a variety of vascular proliferations can be found in the overlying skin ranging from benign lymphovascular proliferations to angiosarcomas. Atypical vascular lesion (AVL) is the term given to a lesion of uncertain malignant potential that has histologic features intermediate between benign and malignant tumors. The majority of reported AVLs are considered benign; however, angiosarcoma has been reported to arise in rare AVLs. Typically the time course between radiation and the development of an AVL is relatively short compared with the time course for the development of angiosarcoma. Histologically it can be difficult to distinguish an AVL from low-grade angiosarcoma. Correlation with clinical and radiographic findings is necessary. Consultation with expert pathologists may be necessary for difficult lesions.

Angiosarcoma.

Angiosarcoma is an uncommon malignant neoplasm of endothelial cells that may occur at any site on the body; however, the unique clinicopathologic presentation in the breast (including its typical dermal tumor location) and well-documented association with prior breast irradiation make it appropriate to discuss as a primary breast neoplastic disorder ( Fig. 13.11 ). Angiosarcoma accounts for 0.04% of primary mammary tumors and approximately 8% of all mammary sarcomas. Before the use of radiation therapy for breast cancer, angiosarcomas of the breast most commonly occurred during the third and fourth decades of life. Approximately 6% to 12% of the cases were diagnosed during pregnancy. Angiosarcoma was historically designated under multiple titles before its current classification, including names such as hemangioendothelioma, hemangioblastoma, hemangiosarcoma, and metastasizing angioma . It carries a uniformly poor prognosis regardless of disease associations or comorbidities, with a 5-year survival of 8% to 50%. Metastases from mammary angiosarcomas have been reported in the lung, skin, liver, bone, central nervous system, spleen, ovary, lymph nodes, and heart.

Angiosarcomas of the breast have increasingly been associated with radiation therapy that occurs before or after surgical intervention for breast cancer. The ever-increasing use of breast conserving therapy and neoadjuvant and adjuvant irradiation projects that the incidence of angiosarcomas will continue to increase. They account for more than 50% of all mammary sarcomas identified in patients who had prior radiation therapy but only 20% of sarcomas in those who had no prior radiation therapy. Angiosarcomas can also occur on the upper extremity or axilla as a result of long-standing lymphedema, which is eponymously referred to as Stewart-Treves syndrome. Those angiosarcomas that arise as a result of chronic lymphedema (i.e., swelling resulting from lymphatic obstruction) usually occur as a complication of mastectomy, dedicated lymphadenectomy, and/or radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. Preoperative diagnosis of angiosarcomas of the breast using fine-needle aspiration is often immensely difficult and diagnosis is best established via incisional biopsy. Irradiation of the breast can produce vascular ectasia or vascular proliferations within the superficial dermis that can exhibit atypical features ( Fig. 13.11A ) but do not meet the histologic criteria for angiosarcoma. These lesions are designated AVLs; however, when a vascular lesion progresses to invade the breast lobules or develops a solid growth pattern ( Fig. 13.11B ), it is diagnostic for angiosarcoma. AVLs may represent vascular proliferations of a reactive angiogenic nature or precursors of vascular lesions of undetermined malignant potential or angiosarcoma. Currently, characterization and diagnosis of these lesions is difficult, and AVLs lack official prognostic factors and guidelines for surgical management. MYC amplification is a consistent feature of radiation-associated angiosarcoma, which can be diagnostically demonstrated via immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization.

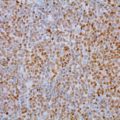

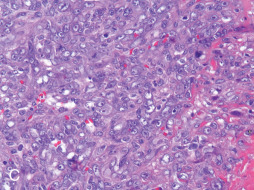

Histologic evaluation of angiosarcoma exhibits anaplastic nuclear features in a hypercellular neoplasm (see Fig. 13.11C ). Histologic sections from primary angiosarcoma of the irradiated breast and primary angiosarcoma of the axilla secondary to lymphedema show dermal infiltration by ill-defined fenestrated vascular spaces lined by atypical endothelial cells. Well-differentiated lesions show an anastomosing network of vessels lined by a single layer of endothelial cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia. Poorly differentiated tumors demonstrate sheets of dedifferentiated cells with frank endothelial nuclear pleomorphism, increasing mitotic activity and necrosis without obvious vascular lumens. Focal papillary protrusions may be observed. Angiosarcomas are immunoreactive for endothelial and vascular antigens, specifically CD31, CD34, ERG, Fli-1, factor VIII–related antigen, D2-40 and Ulex europaeus antigen. Ultrastructural examination can reveal the vascular nature of angiosarcomas by demonstrating Weibel-Palade bodies and pinocytic vesicles.

Treatment involves a multidisciplinary approach because angiosarcomas of the breast are quite resistant to conventional chemotherapy regiments. Angiosarcomas typically extend microscopically beyond their clinical gross margins due to their insidious dermal growth pattern, and therefore simple excision is unacceptable because of its high rate of local recurrence. Surgical treatment of angiosarcoma is usually contraindicated in tumors that extend to vital structures, are of massive size, or are in multicentric tumors; however, early and complete surgical excision of the mass lesion with tumor-free margins should be attempted, if achievable. Doxorubicin-based neoadjuvant therapy is reserved for unresectable tumors, tumors invading the chest wall, and tumors larger than 5 cm. Breast angiosarcomas are best treated with a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy for local control. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy is being used with increasing frequency, although the benefit of adjuvant therapy remains unclear. Axillary dissection is not indicated because these tumors spread in a hematogenous fashion and nodal involvement is rare. In unconventional cases, modified radical mastectomy may be part of the treatment protocol. Radical mastectomy is generally reserved only for tumors with extension to deep fascial planes or the chest wall. The decision for mastectomy is guided by the following factors: size and location of the tumor, presence of multicentricity, capacity to follow the breast by mammography, and physical examination for evidence of postoperative recurrence and patient preference for treatment.

Malignant Adnexal Tumors.

Malignant neoplasms of eccrine or apocrine glands are rare, accounting for less than 0.001% of all primary breast cancers. These tumors generally affect a younger population than conventional invasive mammary carcinoma, usually those in the third to fifth decades. These neoplasms, in general, represent the malignant counterparts of benign adnexal tumors in that they display typical pathologic features of a particular adnexal tumor. In addition they display lymphovascular and/or perineural invasion, atypical or anaplastic morphology, atypical mitotic figures, extensive necrosis, and/or a destructive invasive pattern of growth. Apocrine lesions are postulated to be significantly more common than eccrine lesions, although this distinction is tenuous at best in some cases, and this delineation has generally not been shown to affect prognosis ( Fig. 13.12 ). In some lesions, tumor cells exhibit both eccrine and apocrine differentiation. Malignant adnexal neoplasms usually present as indurated slowly growing plaques with irregular geographic outlines. Malignant adnexal tumors may evolve from benign adnexal tumors or arise de novo. Adnexal carcinomas, like adenomas, may mimic the appearance of breast carcinomas. Both benign and malignant sweat gland tumors can express estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and/or HER2/neu . Immunoperoxidase stains have not been shown to reliably differentiate sweat gland carcinomas from breast carcinomas. The treatment for adnexal carcinomas is surgical therapy with wide margins. Metastatic potential is high in these lesions and prognosis remains poor, even with the administration of combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy regimens.

Secondary Breast Dermatologic Disorders

Secondary Inflammatory Disorders

Infectious Disorders

Erythrasma.

Erythrasma is a chronic cutaneous bacterial infection caused by the organism Corynebacterium minutissimum. Although usually intertriginous, erythrasma presents as a well-demarcated, oval, reddish brown patch with fine scaling. Clinical forms may be diagnosed by characteristic coral-red fluorescence under Wood light. Biopsies often appear unremarkable with hematoxylin and eosin staining; however, gram-positive coccobacilli in the superficial stratum corneum are diagnostic ( Fig. 13.13 ). It is well established that erythrasma, like acanthosis nigricans, can be a presenting sign of diabetes mellitus.