POSTABORTION INFECTION

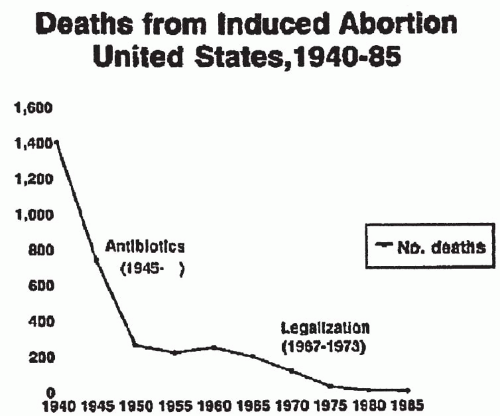

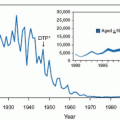

In the last 30 years, medical and legal decisions have changed the practice and outcome of pregnancy termination

(Fig. 12.1). Death and major complications from abortion decreased dramatically as a result of antibiotic availability and legalization of abortion. When death occurs as a result of induced abortion, however, infection is a leading cause.

Risk factors for death after legal abortion are advancing gestational age, advancing maternal age, “black and other” race, and method used (with the lowest risk accompanying procedures used at early gestational ages).

As with risk factors for death after legal abortion, risk factors for major complications after abortion are longer duration of pregnancy and technical difficulties. The rate of infection after first-trimester vacuum aspiration from six studies (1971 to 1987) was 0.1% to 4.7%, whereas for second-trimester procedures from five studies (1971 to 1990) the rate was 0.4% to 2.0%. In prospective studies of prophylactic antibiotics for abortion, the rate was 1% to 10% in those receiving antibiotics and 5% to 23% in those receiving placebo. These wide ranges are a result of the criteria for diagnosis of infection and the method of data collection.

For 2004, a total of 839,226 legal abortions were reported to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) from 49 reporting areas. In 2005, there were 848,163 legal abortions and 10 deaths from complications of legal abortion.

Pathophysiology

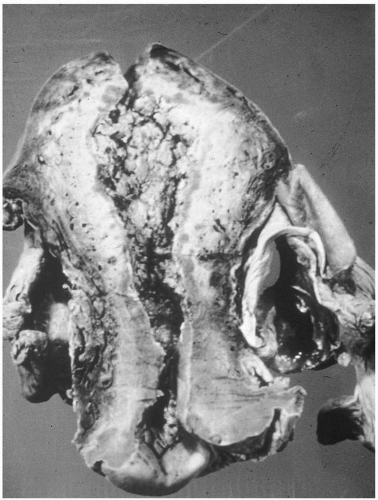

Infection after abortion is an ascending process that occurs more commonly in the presence of retained products of conception or operative trauma

(Fig. 12.2). Perforation of the uterus may be followed by severe infection, whether or not there is bowel trauma. Hysterotomy is rarely indicated for abortion because it has a very high complication rate. Infection after hysterotomy is frequent because there is necrosis, foreign body (suture material) and blood clot in the thick uterine incision, contamination from the lower genital flora, and, often, poor drainage of the uterine cavity.

Diagnosis

For patients who have had an abortion, the diagnosis of postabortion infection often is readily made. Symptoms may include fever, chills, malaise, abdominal pain, and vaginal bleeding, perhaps with passage of placental tissue. Postabortal infection may be more difficult to diagnose in patients who have illegal abortions because of patient denial of the procedure.

Although illegal abortion is now very rare in the United States, septic abortion should be considered in every woman with lower abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding, especially if there is fever and tenderness.

Physical findings may include elevated temperature, tachycardia, and tachypnea. Because bacteremia occurs more commonly with infected abortion than with other pelvic infections, shock may arise from sepsis as well as from blood loss. In the presence of sepsis, the patient may appear agitated, toxic, or disoriented. Usually there is lower abdominal tenderness. On pelvic examination, there often is blood and perhaps a foul odor in the vagina. It is important to look for cervical and vaginal lacerations, especially in a suspected illegal abortion. The cervix is most often open and will readily admit a sponge forceps. If a catheter from an illegal abortion is still in the cervix, it should not be removed immediately, because radiographic techniques can be used to rule out perforation.

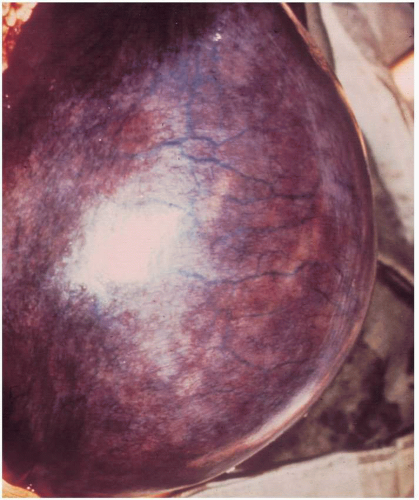

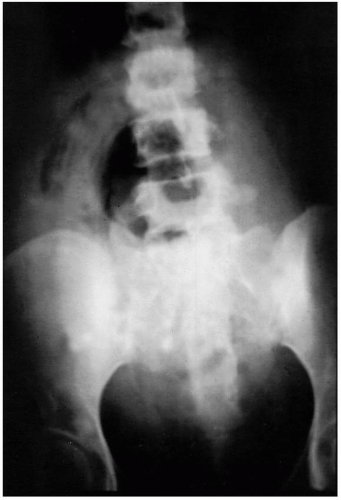

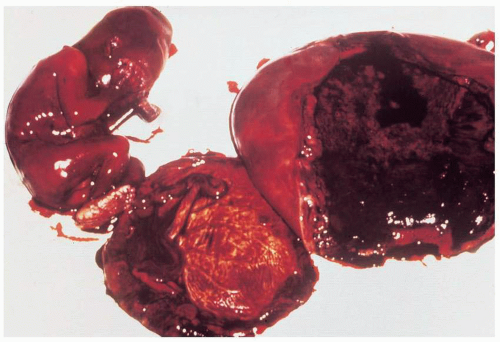

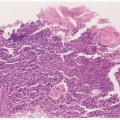

On bimanual examination, uterine tenderness often is noted, and parametrial cellulitis or abscess may be detected. Rarely, gas gangrene of the uterus may be detected by crepitation in the pelvis

(Figs. 12.3, 12.4, and 12.5).Laboratory diagnostic evaluation should include complete blood count, urinalysis, culture and Gram stain of cervical material, two sets of blood cultures, anteroposterior roentgenogram of the abdomen and pelvis, and upright chest x-ray film. Free hemoglobin may be noted in the serum or in the urine in infections caused by Clostridium perfringens or other organisms with hematotoxins. Gram stain of cervical exudate may reveal the predominant organism immediately. Results of blood cultures commonly are positive in septic abortion. Roentgenograms in patients with suspected illegal abortions help rule out a foreign body or free air under the diaphragm resulting from perforation. Gas in the uterus is a late sign of uterine gangrene. Ultrasound examination may be used as the initial imaging technique, as it may detect retained placental tissue, foreign body, and possibly air in the pelvic structures. Blood should be obtained for typing and potential cross-matching.

In 2005, four cases were reported of fatal toxic shock syndrome associated with

Clostridium sordellii after medical abortion. All occurring in young, previously healthy women, death occurred within 1 week of the medically induced abortion.

Notable features included absence of fever but a dramatic leukemoid reaction (45 to 120,00/mm

3), fluid sequestration, hemoconcentration, refractory tachycardia and hypotension, and marked edema of infected tissues, without gas or extensive myonecrosis. The estimated attack rate was 1 in 100,000 medical abortions in the United States.

C. sordellii is an infrequent human pathogen, having been reported to cause pneumonia, endocarditis, arthritis, peritonitis, myonecrosis, and rarely, bacteremia/sepsis, mainly in debilitated patients. It is rarely found in the genital tract, although other clostridial species are found in 4% to 18% of vaginal cultures of healthy women. This postmedical abortion toxic shock is fulminant and results from specific exotoxins. There are limited data regarding treatment, but current recommendations are:

As with the other several histotoxic clostridial infections (such as C. perfringens myonecrosis), removal of infected tissues, usually by hysterectomy;

Administration of intravenous antibiotics with good anaerobic activity, such as penicillin, ampicillin, cefoxitin, clindamycin, metronidazole, or others; and

Administration of exquisite supportive care, typically in an ICU.

There are no data on the use of immunoglobulins or antilethal toxin antibodies.

Prevention

Prevention of infected abortion consists of avoiding unplanned pregnancies by access to, and proper use of, contraceptives. Because infection is less common after legal abortion than after illegal abortion, an additional important means to prevent postabortion infection is to provide access to all women to early, safe, legal abortion. Technical considerations include avoiding perforation and incomplete abortions during curettage procedures. Hysterotomy is accompanied by so large an increase in risk that it is rarely if ever indicated. Hysterectomy for abortion and sterilization is best reserved for women with additional uterine conditions.

In a meta-analysis, it was shown that antibiotics at induced abortion led to a substantial protective effect in both high-risk (history of pelvic inflammatory disease, C. trachomatis, or bacterial vaginosis) and low-risk women. It was estimated that periabortal antibiotics may prevent up to half of all postabortal infections.

Treatment

The essentials of treating infected abortion are (a) supportive therapy including replacement of blood and fluids; (b) surgical removal of any infected tissue; and (c) appropriate antibiotic therapy. After proper diagnostic studies have been carried out, vigorous parenteral antibiotic therapy should be administered. Because of the likelihood of multiple organisms and bacteremia in septic abortion, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy such as clindamycin plus gentamicin is appropriate for initial therapy. For the patient in septic shock, addition of penicillin G or ampicillin is advisable.

After antibiotic therapy is initiated, surgical drainage is essential unless there is confidence that infection is confined to the endometrium and there is no retained placental tissue. Prompt curettage usually suffices. In experienced hands and with special instruments, the uterus may be safely evacuated transcervically at up to 20 to 24 weeks, with ultrasound guidance. Delaying evaluation of the uterus because of the patient’s poor condition is a mistake in management that may prove fatal.

When the uterus is too large for an operator to undertake suction curettage, high-dose oxytocin administration often is successful. Rather than increasing the dose of oxytocin stepwise, we start with 300 mU/min of oxytocin in normal saline (0.9%) or in Ringer’s solution. At this dose, oxytocin exerts an antidiuretic effect. See

Box 12.1 for measures to avoid water intoxication.

Fifteen-methyl prostaglandin F2a (carboprost tromethamine), 250 mg intramuscularly every 2 to 3 hours, has been recommended. If none of these drugs is available, a large Foley catheter (50-mL balloon) may be placed in the lower uterus. The use of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) suppositories is contraindicated in the presence of sepsis because it causes fever.

In some situations, laparotomy may be indicated to control infection. Indications for exploratory laparotomy are shown in

Box 12.2.

It must be emphasized that the mere isolation of

Clostridium species from the pelvis does not necessarily signify life-threatening infection or the need for laparotomy. Instead, the initial treatment for a patient with presumed clostridial infection is penicillin in large doses, curettage, and supportive therapy. A pelvic roentgenogram should be obtained because it may reveal myometrial gas, but this occurs late if at all (

Fig. 12.4). If there is no response or deterioration, laparotomy is indicated.

Prognosis

The overall outlook for a patient with infected abortion is good, but this condition must be considered a life-threatening infection. In the United States from 1972 to 1981, 273 women died of abortion complications, many from infection. Of these, 180 were from legal abortion, 83 from illegal abortion, and 10 from unknown type of abortion. From 1982 to 1991, there were 121 abortion deaths (111 legal, 7 illegal, and 3 unknown), whereas for 1992 to 2002, there were 92 abortion-related deaths (86 legal, 4 illegal, and 2 unknown). In 2003, there were 10 deaths from complications of illegal abortions (a rate of 1.18 deaths/100,000 procedures). There were no deaths reported in 2003 that were caused by legal abortion. Reasons for these improvements in outcome are improvement in physician skills; introduction of improved methods (suction curettage); and availability of safe, early, and legal abortion.

Reproductive potential after an infected abortion may be compromised by Asherman syndrome, pelvic adhesions, or incompetent cervix. However, the CDC concluded that vacuum aspiration overall does not adversely affect fecundity but that dilation and evacuation for second-trimester termination increases the risk of subsequent spontaneous abortion, prematurity, and low birth weight infants.

BACTEREMIA

The principal pathogens responsible for bacteremia in obstetric-gynecologic patients are coliform organisms, particularly Escherichia coli, group B streptococci, anaerobic streptococci, and Bacteroides sp. Other significant causative organisms include Clostridium sp, enterococci, and, rarely, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Multiple aerobic and anaerobic organisms may be responsible for bacteremia in certain patients. The reported overall incidence of bacteremia is about 7.0 per 1,000 obstetric-gynecologic admissions.

Most obstetric-gynecologic patients with bacteremia respond promptly to intravenous antibiotic therapy, and their prognosis is better than that of medical patients with bacteremia. It has been reported that overall, bacteremic obstetric patients and nonbacteremic obstetric patients with similar infections have similar outcomes. However, sepsis develops occasionally, with an appreciable mortality rate.

Recognizing that antibiotic use often is inappropriate (22% to 64% of the time in recent reviews) and that inappropriate antibiotic use is accompanied by adverse results, standards of treatment for bacteremia have been published. These standards are given in

Table 12.1.

Most nonbacteremic obstetric-gynecologic patients who have genital tract infections respond promptly to antibiotic and do no require therapy for more than 24 to 48 hours after resolution of fever and other signs of infection. Patients with

a bacteremic genital tract infection should be considered differently. For most bacteremic patients, we continue an appropriate intravenous antibiotic therapy for 48 hours after resolution of infection and then prescribe an oral antibiotic to complete a 7- to 10-day course. Some bacteremias such as those caused by

S. aureus should be treated with intravenous therapy for a longer period (e.g., 10 to 14 days) to prevent metastatic infection.