638

Polypharmacy

Ginah Nightingale and Manpreet K. Boparai

BACKGROUND

Men and women aged 65 years or older are the biggest consumers of medications (1). Nearly one-third of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older take more than five prescription medications, and almost 20% take 10 or more (1,2). Polypharmacy is a significant public health problem that disproportionately affects older adults, particularly those with multiple comorbid conditions. Polypharmacy is commonly defined as concurrent use of five or more medications, including prescription, nonprescription, and complementary and herbal supplements (3–5). Polypharmacy can also be defined by the use of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) which are associated with an increased risk for adverse drug effects in older adults. A publication by Bushardt and colleagues suggested that there are 24 distinct definitions of polypharmacy, encompassing concepts ranging from unnecessary or inappropriate medication use to the use of excessive numbers of medications (6).

Although the use of many medications may be good practice for the treatment of some chronic medical conditions, the addition of cancer-related therapy (to existing polypharmacy) adds to the prevalence of the use of multiple medications and/or the consumption of inappropriate medications. The multiple layers of specialists, primary care, and allied health professionals in the continuum of care make this population particularly prone to medication errors attributable to medication changes, complex regimens, and incomplete information hand-off between providers. As a consequence, there may be an increased risk for adverse drug events, drug–drug interactions, nonadherence, and in some cases an increased risk of hospitalization and increased health care utilization (7–13).

IMPORTANT CONSIDERATIONS WHEN PRESCRIBING FOR OLDER ADULTS

Prescribing for older adults presents unique challenges. Many medications must be used with caution due to age-related physiologic changes, and care must be taken when determining the appropriate dosages. Increased volume of distribution may result from the increase in body fat relative to skeletal muscle with aging. Lipophilic drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines) have an increased volume of distribution, taking longer to reach a steady state and longer to be eliminated. 64Therefore, the starting doses should be decreased. A natural decline in renal function with age may result in decreased drug clearance. Decreased drug clearance and larger drug reservoirs prolong half-lives and lead to increased drug concentrations. Hepatic function also declines with age, further affecting drug metabolism and leading to adverse drug reactions (ADRs) (14).

POLYPHARMACY AND PIM USE

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Older Adult Oncology Guidelines recommend a thorough evaluation of the medication list and PIMs, with subsequent discontinuation of nonessential or high-risk medications (15). Patients should also be asked about herbal medications, as patients may not volunteer this information nor recognize the importance of discussing this with the medical team. The prevalence of polypharmacy in the ambulatory older adult oncology population ranges from 48% to 80% and the prevalence of PIM use ranges from 8% to 51% (7–20). This variability may be attributed to the methodology used for the evaluation (e.g., self-reports, medical records extraction, pharmacist assessment), screening tools, and definitions of polypharmacy and inappropriate medications.

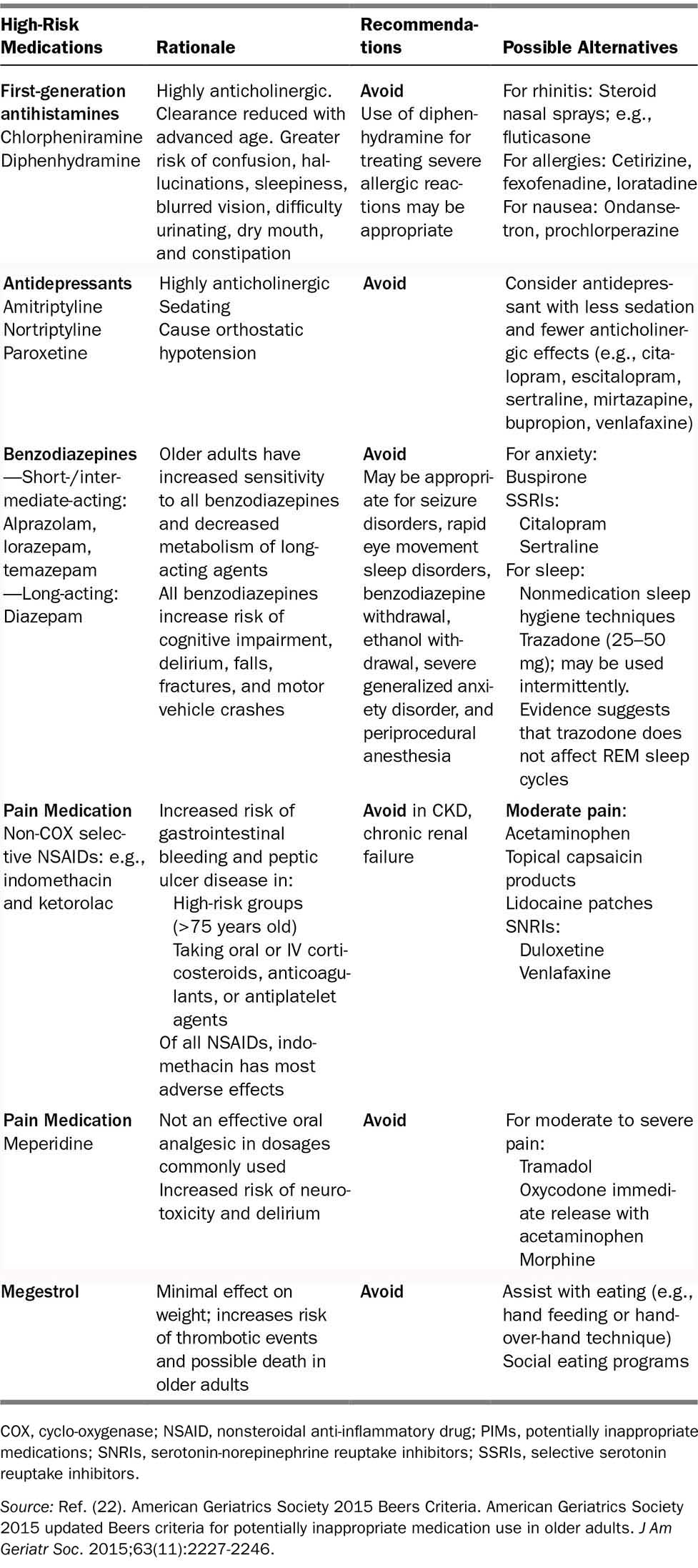

Similar to the heterogeneity that exists with defining polypharmacy, heterogeneity exists with identifying and categorizing PIMs. PIMs are largely referred to as medications lacking evidence-based indications, medications with treatment risks that outweigh benefits, medications that are significantly associated with ADRs, or those that may potentially interact with other medications or other diseases (21). The most current, evidence-based, validated criteria and screening tools to capture PIMs include the 2015 Beers Criteria (Table 8.1), the Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions (STOPP), and the Medication Appropriateness Index (7–26) (Tables 8.2 and 8.3).

TABLE 8.1 Examples of PIMs—2015 Beers Criteria

65

66TABLE 8.2 Examples of PIMs—STOPP Criteria

Cardiovascular System | Avoid Use |

Digoxin | Long-term use >125 μg/d with renal dysfunction |

Loop diuretics | For dependent ankle edema only (no signs of HF); compression hosiery usually more appropriate |

Thiazide diuretics | With history of gout (may exacerbate gout) |

Noncardioselective beta-blockers | With COPD (risk of increased bronchospasm) |

Diltiazem or verapamil | With NYHA class III or IV HF (may worsen heart failure) |

Calcium channel blockers | With chronic constipation (may exacerbate constipation) |

Central Nervous System/Psychotropic Drugs | Avoid Use |

Tricyclic antidepressants | With dementia (risk of worsening cognitive impairment) |

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | With hyponatremia |

Gastrointestinal System | Avoid Use |

Proton pump inhibitors | For PUD at full therapeutic doses for >8 weeks |

Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs | With moderate to severe hypertension or HF |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF, heart failure; PIMs, potentially inappropriate medications; PUD, peptic ulcer disease; STOPP, Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions.

Source: Adapted from Refs. (23–25).

67TABLE 8.3 Medication Appropriateness Index Criteria

1. Is there an indication for the drug? 2. Is the medication effective for the condition? 3. Is the dosage correct? 4. Are the directions correct? 5. Are the directions practical? 6. Are there clinically significant drug–drug interactions? 7. Are there clinically significant drug–disease/condition interactions? 8. Is there unnecessary duplication with other drugs? 9. Is the duration of therapy acceptable? 10. Is this drug the least expensive alternative compared with others of equal usefulness? |

Source: Ref. (26). Samsa GP, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, et al. A summated score for the medication appropriateness index: development and assessment of clinimetric properties including content validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(8):891-896.

a. The Beers Criteria is the most frequently used tool in the United States, supported and endorsed by the American Geriatrics Society (AGS). A consensus guideline, the Beers Criteria was first published in 1991 and last updated in 2015. It identifies 40 potentially problematic medications or classes of medications organized across five lists.

b. STOPP is a European-based tool developed on the basis of expert consensus and evidence-based criteria. It includes drug–drug and drug–disease interactions, drugs that adversely affect seniors at risk of falls, and medication duplications.

c. The Medication Appropriateness Index measures the appropriateness of prescribing using 10 criteria for each medication to determine whether it is appropriate, marginally appropriate, or inappropriate.

There are no head-to-head trials that recommend the use of one screening tool over another, so each of these tools is considered an option for use in practice. The AGS stated that the STOPP criteria should be used in a complementary manner with the Beers Criteria largely because there are some notable differences between the tools. It is important to highlight high-risk medications that have been associated with hospital admissions in older persons: insulin, warfarin, oral antiplatelet agents, and oral hypoglycemic agents. Especially careful attention is warranted with these agents (27).

MEDICATION ADHERENCE

Medication adherence has also become increasingly important in the setting of polypharmacy, especially given the acceleration expansion and development of oral chemotherapy. A systematic review of determinants and influences on adherence to oral chemotherapy drugs showed that older age was a factor (28). Barriers to adherence can occur on the individual or system level and interventions to improve adherence should be multifactorial (Table 8.4). The Morisky Medication Adherence Scale is a validated adherence assessment tool, which has been used for several chronic health conditions but has not been validated for use in oncology (29). Thus, a research gap exists regarding validated tools to measure medication adherence in the setting of polypharmacy and cancer.

68TABLE 8.4 Interventions to Improve Medication Adherence

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree