INCIDENCE AND ETIOLOGY

Penile cancer most commonly affects men between 50 and 70 years of age. The tumor is not unusual in younger men; in one large series, 22% of patients were younger than 40 years, and 7% were younger than 30 years (1). In 2015, there were an estimated 1,820 new cases in the United States (2).

Penile carcinoma accounts for less than 1% of all malignant neoplasms among men in the United States and Europe, but it may represent up to 20% of malignant neoplasms in men in some Asian, African, and South American countries (1). These differences are thought to be related to the prevalence of neonatal circumcision, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, and hygienic practices. Rates of HPV vaccination will likely become a factor in the future (3).

Among uncircumcised tribes of Africa and within uncircumcised Asian cultures, penile cancer may amount to 10% to 20% of all malignant neoplasms in men (1). Carcinoma of the penis is particularly rare among the Jewish population, for whom neonatal circumcision is a universal practice (4). The annual number of new cases in total per year worldwide has been estimated at approximately 26,000 (5). Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common histologic subtype, accounting for over 95% of cases (Table 38-1) (6).

RISK FACTORS

The risk of penile cancer varies according to circumcision practice, hygienic standard, phimosis, number of sexual partners, HPV infection, exposure to tobacco products, and other factors (1,5). Neonatal circumcision has been well established as a prophylactic measure that removes most of the risk of penile carcinoma because it eliminates the closed preputial environment where penile carcinoma most commonly develops. Phimosis is found in 25% to 75% of patients with penile carcinoma described in most large series. Reddy et al (7) studied the foreskins of 26 men undergoing circumcision because of phimosis and found epithelial atypia in one-third of the specimens. Data from most large series show that neonatal circumcision is protective, whereas circumcision delayed until after puberty is not (8).

Although HPV is not a reportable sexually transmitted disease, the number of new genital HPV infections has been estimated at 500,000 to 1 million annually in the United States (9). The terms genital condyloma, venereal warts, genital warts, and genital HPV infection all refer to a sexually transmitted disease caused by HPV. Factors associated with higher rates of infection with HPV include presence of foreskin, increasing numbers of sexual partners, lack of condom use, and smoking (10). The overall prevalence of HPV in females was found to be 26.8% among US females aged 14 to 59 years and was highest among women aged 20 to 24 years (44.8%) (11). Human papillomavirus is recognized as the principal etiologic agent in cervical dysplasia and cervical cancer (12).

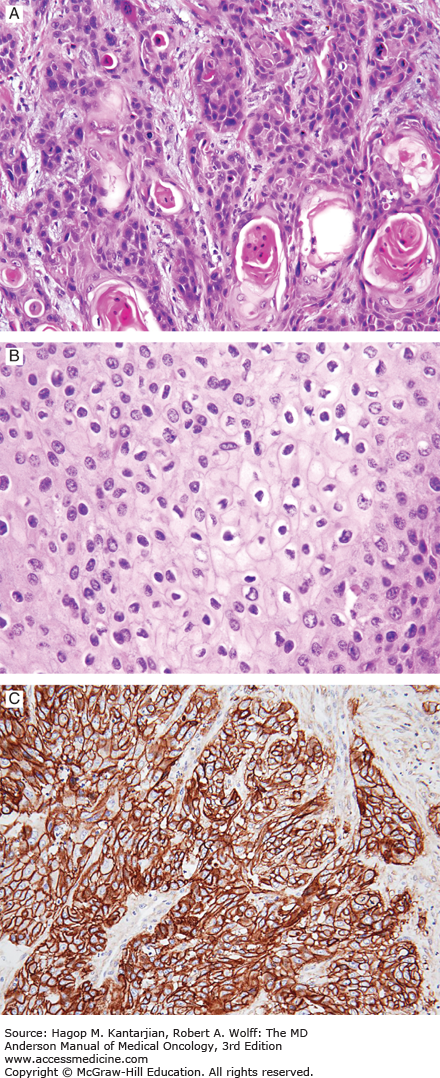

On histologic examination, the koilocyte—a cell characterized by an empty cavity surrounding an atypical nucleus—is pathognomonic for HPV infection (Fig. 38-1) (13). DNA hybridization techniques have been used to identify and classify HPV infections, and some 60 genotypes of HPV virus have been identified that involve the genital tract (14). Virus types 6, 11, and 42 to 44 are associated with gross condylomata and low-grade dysplasia, whereas types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, and 39 have a higher association with malignant disease (15).

In men, a personal history of genital condylomata has been associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the penis (10). Malignant transformation of condylomata to squamous cell carcinoma has been reported (16). Condylomata acuminata located in the perianal, scrotal, and oral areas have also demonstrated malignant degeneration. An increased incidence of penile intraepithelial neoplasia has been found in the male partners of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (3).

More than 25 types of HPV infect genital sites. It appears that HPV-16 is the most frequently detected type in primary carcinomas and has also been detected in metastatic lesions (17). Thus, preventive strategies are relevant, and prophylactic HPV vaccines are available for both men and women (3). The prevalence of HPV vaccination in the United States, however, remains disappointingly low.

Although HPV infection is probably an important factor in the development of penile cancer, with evidence that 31% to 63% of tumors are HPV related, its presence is not invariable (18). Other factors must be involved in the development of the disease or its subtypes. Human papillomavirus is most associated with the basaloid and warty tumor subtypes, which were found to contain HPV DNA in 80% to 100% of cases.

Patients with HPV-related penile cancer appear to have a better prognosis than those with HPV-unrelated tumors. A population-based study found that the detection of HPV DNA in penectomy specimens was associated with a significant advantage in disease-specific survival (96% vs 82%) (19). Immunohistochemical detection of p16, which is a marker for HPV infection, was also associated with improved outcome (20). Whether HPV is predictive of response to treatment (eg, chemotherapy) is unknown.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection may predispose affected patients to rapid development of squamous carcinoma from preexisting condyloma infection (21). Poblet et al (22) reported on two cases of coexisting HIV-1 and HPV infection and postulated that HIV-1 could synergize with HPV to increase the progression of HPV penile lesions into penile carcinoma. Whereas there is evidence supporting this effect in cervical and anal neoplasia (23), definitive proof for penile cancer awaits further study.

MOLECULAR FEATURES

The viral genes E6 and E7 are overexpressed in HPV-transformed cells, and they are known to interact with the RB1 and TP53 tumor suppressor pathways. These molecular events are known to play a critical role in the development of cervical cancer (12), and a similar mechanism probably exists in HPV-related cases of penile cancer (3,18).

The tumor suppressor gene TP53 is commonly mutated in human solid tumors, where the abnormal protein accumulates and can be detected by positive immunostaining. In penile cancer, positive p53 immunostain is an independent predictor of lymph node metastasis (24). In a study by Lopes et al (25), the p53-positive cases had a lower overall survival and higher incidence of lymph node metastasis. Martins et al (24) studied 50 patients, of which 14 had clinically positive lymph nodes. After penectomy, tumors were stained for p53 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), and these results were compared with stage, grade, nodal status, and cause of death. Overexpression of p53 was associated with pT classification, grade, nodal metastasis, and cause-specific survival. Also, PCNA was associated with nodal metastasis but not survival. Of note, TP53 mutations would not be expected to occur in HPV-related tumors because p53 is inactivated by HPV viral proteins.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and cellular adhesion molecules have been studied in penile cancer. Campos et al (26) measured MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression and found that MMP-9 was an independent risk factor for disease recurrence. In the same study, low E-cadherin was associated with a greater risk of lymph node metastasis. A Chinese study (27) found that 45% of tumors had low E-cadherin, and that it was associated with shorter cause-specific survival. These alterations have been found in both HPV-related and unrelated penile tumors (5).

Multiple studies have shown that the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is overexpressed in the majority of penile cancer cases (28,29). Activating mutations of EGFR or KRAS, on the other hand are uncommon. Several published case reports and one case series suggested that EGFR is a useful target for therapy in metastatic penile cancer (30,31,32).

PATTERN OF METASTASIS

Penile cancers have a predictable pattern of local, regional, and systemic spread. The earliest route of dissemination from the penis is metastasis to the regional femoral and iliac nodes. The lymphatics of the prepuce form a connecting network that joins with the lymphatics from the skin of the shaft. These tributaries drain into the superficial inguinal nodes. The lymphatics of the glans join the lymphatics draining the corporal bodies, and they form a collar of connecting channels at the base of the penis that also drain by way of the inguinal lymph nodes. From there, drainage is to the pelvic nodes (external iliac, internal iliac, and obturator). Multiple cross connections exist at all levels of drainage, so that penile lymphatic drainage is bilateral to both inguinal areas (33).

Tumor grade, lymphovascular invasion, and perineural invasion appear to be the most important pathologic prognostic factors for nodal spread and mortality (34). Other frequently cited risk factors are pT classification, tumor thickness, anatomical site (proximal vs distal), pathologic subtype, urethral invasion, and positive margins of resection.

Lymphovascular invasion in the primary tumor has significant prognostic importance. Studies have assessed its presence or absence and found that it was an important predictor of nodal metastasis (35). The pathologist should specifically comment on the presence or absence of vascular invasion in the surgical specimen. Perineural invasion was found to be present in 36% of cases analyzed in a multi-institutional data set of 134 patients and was also a strong predictor of lymph node metastasis (36).

Metastatic penile cancer is characterized by a relentlessly progressive course, causing death for the majority of untreated patients within 2 years (37). Metastatic enlargement of the regional nodes eventually leads to skin necrosis, chronic infection, and death from sepsis, hemorrhage secondary to erosion into the femoral vessels, and failure to thrive.

Clinically detectable distant metastatic lesions to the lung, liver, bone, or brain are uncommon at initial presentation. Such metastases usually occur late in the course of the disease after the local lesion has been treated. Distant metastases in the absence of regional node metastases are unusual.

EVALUATION OF THE PATIENT

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) seventh edition TNM staging system for penile cancer (Table 38-2) differs from the sixth edition in that pT1 tumors are stratified regarding whether there is high-grade histology or lymphovascular invasion (pT1b) (38). Considering pathologic nodal factors further, the seventh edition distinguishes patients with a single positive node (N1) from those with multiple or bilateral nodes (N2) and further recognizes the ominous prognosis (5%-18% 5-year survival) associated with extranodal extension of cancer.

| Primary Tumor (T) | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| Ta | Noninvasive verrucous carcinoma |

| T1a | Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue without lymph vascular invasion and is not poorly differentiated (ie, grades 3-4) |

| T1b | Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue and exhibits lymph vascular invasion or is poorly differentiated |

| T2 | Tumor invades corpus spongiosum or cavernosum |

| T3 | Tumor invades urethra |

| T4 | Tumor invades other adjacent structures |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | |

| Clinical Stage Definition | |

| CNX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| cN0 | No palpable or visibly enlarged inguinal lymph nodes |

| cN1 | Palpable mobile unilateral inguinal lymph node |

| cN2 | Palpable mobile multiple or bilateral inguinal lymph nodes |

| cN3 | Palpable fixed inguinal nodal mass or pelvic lymphadenopathy unilateral or bilateral |

| Pathologic Stage Definition | |

| PNX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| pN0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| pN1 | Metastasis in a single inguinal lymph node |

| pN2 | Metastasis in multiple or bilateral inguinal lymph nodes |

| pN3 | Extranodal extension of lymph node metastasis or pelvic lymph nodes(s) unilateral or bilateral |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasisa |

A study from the Netherlands Cancer Institute evaluated the practical and prognostic value of the sixth edition TNM classification for penile carcinoma (Table 38-3) (39). The current T2 category combines tumors that invade either the corpus spongiosum or the corpora cavernosa (38). The 5-year disease-specific survival for tumors invading the corpus spongiosum in the Dutch series was 77.7% and for tumors invading the corpora cavernosa was 52.6%, suggesting that the capacity of a tumor to penetrate the tunica albuginea covering the corpora cavernosa is a more invasive characteristic. The Dutch investigators also suggested that the T3 category appears to be obsolete because a distally located tumor that invades the urethra can still be treated with good prognosis; they proposed that invasion of the corpora cavernosa should be designated T3 (40).

The Dutch study did not find a significant difference in 5-year disease-specific survival between the N1 and N2 category (70.2% and 58.3%, respectively; P

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree