Pelvic exenteration is a major surgical procedure that involves the en bloc removal of some or all of the pelvic organs. The main indication for the operation is to control isolated central pelvic recurrences of cervical and other gynecologic malignancies, after primary treatment with pelvic radiation therapy. In geographic regions of the world where modern radiation can be delivered, central control rates have improved, and the need for radical resection of pelvic recurrences has decreased.

While some European centers have advocated pelvic exenteration for patients with advanced primary cervical cancer (1), most centers restrict the operation to patients with a central recurrence following chemoradiation. The only exception would be patients with stage IVA disease and a rectovaginal or vesicovaginal fistula.

Pelvic exenteration provides the only hope for cure in women with recurrent pelvic malignancies after radiation therapy. Most procedures are done for recurrent cervical cancer. Operative morbidity and mortality can be decreased by careful patient selection, attention to intraoperative technique, excellent postoperative care, and early management of complications. The 5-year survival rate is acceptable given the lack of satisfactory alternative treatments. With modern reconstructive and rehabilitative techniques, the patient can maintain a near-normal lifestyle, but sexual functioning will always be significantly impaired.

History of Exenteration

The first series of pelvic exenterations for gynecologic cancer was published in 1946 by Alexander Brunschwig, who summarized the outcome of 22 patients, 5 of whom died of the operation itself (2). The original procedure included sewing both ureters into the colon, which was then brought out as a colostomy. Since these humble beginnings, there have been major improvements in the selection of patients, operative technique, blood product use, antibiotic availability, and intensive postoperative medical management.

The operation gained wider acceptance after Bricker (3) published his technique of isolating a loop of ileum, closing one end, anastomosing the two ureters to this end, and bringing the other out as a stoma. This eliminated the hyperchloremic acidosis and markedly diminished the recurrent pyelonephritis and renal failure that were experienced with the wet colostomy. The popularity of the Bricker ileal loop was aided by the development of watertight stomal appliances.

Failure of the small bowel anastomosis to heal because of radiation fibrosis in some patients led to the use of a segment of nonirradiated transverse colon for the conduit (4). Further reductions in bowel complications occurred with the use of surgical staplers, which decreased the operative time, blood loss, and subsequent medical complications (5). Further refinements in the urinary diversion led to the continent urinary reservoir, which is described in Chapter 20.

As a higher percentage of patients became long-term survivors, the desire to improve quality of life led to reconstructive techniques for the vagina and the colon. Today, the patient undergoing pelvic exenteration may have a colonic J-pouch rectal anastomosis, vaginal reconstruction, and continent urinary diversion, allowing her to enjoy a near-normal quality of life without major alterations in her physical appearance.

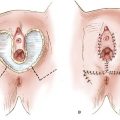

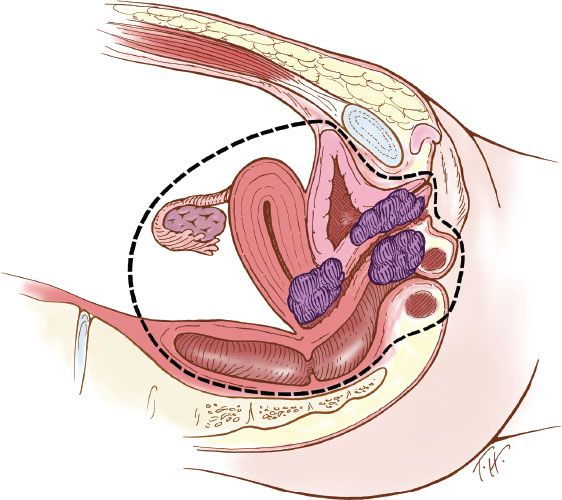

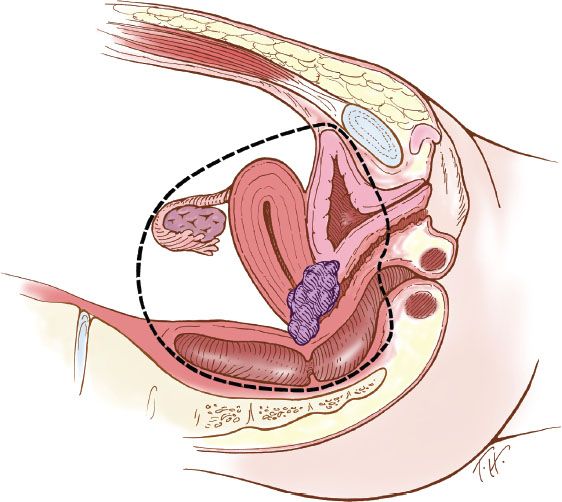

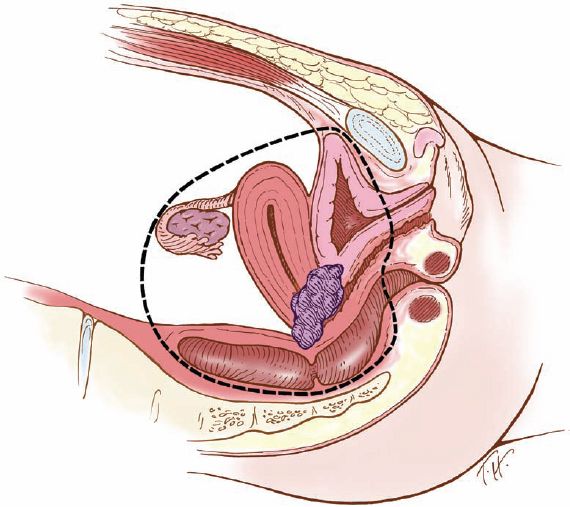

The terminology of pelvic exenteration has changed as the operations have been tailored to remove the tumor and only the involved organs. The total exenteration performed by Brunschwig included the bladder, uterus, vagina, anus, rectum, and sigmoid colon (2). It usually included a large perineal phase (Fig. 23.1). This would lead to a permanent colostomy and urinary stoma. Rutledge et al. (6) and Symmonds et al. (7) reported decreased morbidity and acceptable survival when performing anterior exenteration, which removed the uterus, bladder, and various amounts of the vagina (Fig. 23.2). Total pelvic exenteration with rectosigmoid anastomosis (supralevator) became possible with the development of circular staplers. The rectum is excised to within 2 to 3 cm of the anal canal, and the levator support of the anal canal and perineal body is preserved (Fig. 23.3). The posterior exenteration removes the uterus, vagina, and portions of the rectosigmoid and anus. It is rarely performed today. Vaginal reconstructive techniques are discussed in Chapter 20.

Figure 23.1 Total pelvic exenteration with perineal phase. This operation includes removal of the bladder, uterus, vagina, anus, rectum, and sigmoid colon, as well as performance of a perineal phase.

Figure 23.2 Anterior pelvic exenteration. This operation includes removal of the bladder, uterus, and varying amounts of the vagina, depending on the extent of disease.

Indications

The most common indication for pelvic exenteration is recurrent or persistent cancer of the cervix after radiation therapy. Some of the early series reported pelvic exenteration as primary therapy for stage IVA cervical cancer, and cancer of the vulva with urethral, vaginal, or rectal invasion. With modern radiation therapy, the use of exenteration as primary therapy is uncommon.

Exenteration has also been used for endometrial carcinoma, vaginal cancer, rhabdomyosarcoma, and other rare miscellaneous tumors, whenever ultraradical central resection of the cancer was feasible and there was no evidence of systemic or lymphatic spread.

Patients with endometrial cancer have a high likelihood of spread beyond the pelvis and are, in general, poor candidates for exenterative surgery. The survival rate for highly selected patients with endometrial cancer undergoing exenteration is less than 20% at 5 years (8). To debulk ovarian cancer optimally, a modified posterior exenteration is often performed, which includes en bloc resection of the pelvic peritoneum, uterus, tubes, ovaries, and a segment of rectosigmoid. It usually preserves most of the rectum and allows for a rectal anastomosis. Because there is ovarian cancer left behind, the procedure violates the principle that exenterative surgery is meant to be curative. In the treatment of ovarian cancer, modified exenteration is performed as part of a cytoreductive procedure and is followed by chemotherapy.

Patient Selection

The medical evaluation begins with histologic confirmation that cancer is present. The patient should have no other potentially fatal disease, and her general medical condition must be adequate for a prolonged operative procedure (up to 8 hours) with considerable fluid shifts and blood loss.

Figure 23.3 Supralevator total pelvic exenteration. This operation removes the uterus, vagina, and portions of the rectosigmoid colon above the levator ani muscles, with colonic reanastomosis.

The search for metastatic disease is imperative. The physical examination should include careful palpation of the peripheral lymph nodes and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytologic analysis of anything suspicious. Particular attention should be paid to the groin and supraclavicular nodes. A random biopsy of nonsuspicious supraclavicular lymph nodes has been advocated but is not routinely practiced (9).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been evaluated for preoperative assessment of the pelvic disease (10). Popovich et al. evaluated 23 patients before pelvic exenteration for tumor extension to the bladder, rectum, or pelvic sidewall, and presence and location of lymphadenopathy. In four patients (17.4%), the MRI was falsely positive for pelvic sidewall infiltration, and in one patient (4.3%), it was falsely negative.

A more recent MRI study of 50 patients undergoing a pelvic exenteration by Donati et al. from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center assessed the accuracy of two readers for bladder, rectal, and pelvic sidewall invasion (11). Of 23 patients with bladder invasion on final pathology, both readers correctly identified 20 patients (86%). There were two false positives for bladder invasion (4%). Rectal invasion occurred in 16 patients and was correctly identified in 13 (81%) and 12 (75%) patients by the two readers, respectively. There was one false positive for rectal invasion (2%). Eight patients had pelvic sidewall invasion; six patients (75%) and seven patients (87.5%) were correctly identified by the two readers, respectively. Similarly, pelvic sidewall invasion was overcalled in 2% and 4% of cases by the two readers.

MRI is a useful modality to evaluate the extent of local recurrence, but overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of rectal, bladder, and sidewall involvement may occur, particularly in the irradiated pelvis.

A computed tomographic (CT) scan of the chest, pelvis, and abdomen has been considered routine in the past for the detection of lung, liver, and lymph node metastases in particular, but has recently been replaced by positron emission tomography (PET).

Lai et al. from Taipei evaluated the PET scan for the restaging of cervical carcinoma at the time of first recurrence (12). Forty patients had a PET scan, together with computed tomography and/or MRI. Twenty-two patients (55%) had their treatment modified as a result of the PET findings. PET was significantly superior to CT/MRI (sensitivity = 92% vs. 60%; p < 0.0001) in identifying metastatic lesions. When compared with an earlier cohort of patients who did not undergo restaging with PET, there was a significantly better 2-year overall survival (72% vs. 36%; p = 0.02).

Husain et al. used FDG PET to determine metastatic disease prior to pelvic exenteration or radical resection in 27 patients with recurrent cervical or vaginal cancers (13). They found that FDG PET had a high sensitivity (100%), and a specificity of 73% in detecting sites of extrapelvic metastasis.

Chung (14) performed PET/CT scans in 52 patients suspected of having recurrent cervical cancer. Twenty-eight of 32 patients (87.5%) with positive scans were proven to have recurrent disease. Seventeen of 20 patients (85%) with negative PET CT scans had no evidence of disease, giving a sensitivity of 90.2% and a specificity of 81%.

The role of PET/CT in detecting the extent of pelvic recurrence was recently addressed by Burger et al. from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (15). Thirty-one patients had PET/CT within 90 days of a pelvic exenteration. Two readers blindly read the PET/CT to determine invasion of bladder, rectum, vagina, and pelvic sidewall. Bladder invasion was found in 13 patients (42%) and correctly identified in 9 cases (69.2%) by one reader and 10 cases (76.9%) by the second. Rectal invasion was found in nine cases (29%) and correctly identified in six (66.6%) by both readers. Pelvic sidewall invasion is the most important local recurrence to identify for the surgeon. In this paper, pelvic sidewall involvement was found in five patients (16%) at the time of surgery and it was correctly identified in three cases (60%) by one reader and four cases (80%) by the other. Both readers had one (10%) false-positive case for pelvic sidewall involvement. Thus PET/CT was not effective in detecting pelvic sidewall disease.

Extension of the tumor to the pelvic sidewall is a contraindication to exenteration; however, this may be difficult for even the most experienced examiner to determine because of radiation fibrosis. If any question of resectability arises, the patient should be given the benefit of exploratory laparotomy and parametrial biopsies.

Laparoscopy has been reported to be useful for the assessment of lymph nodes as well as the resectability of disease in the pelvis. In the hands of a highly skilled laparoscopic surgeon, this may be an option (16).

The clinical triad of unilateral leg edema, sciatic pain, and ureteral obstruction is nearly always indicative of unresectable cancer on the posterolateral pelvic sidewall.

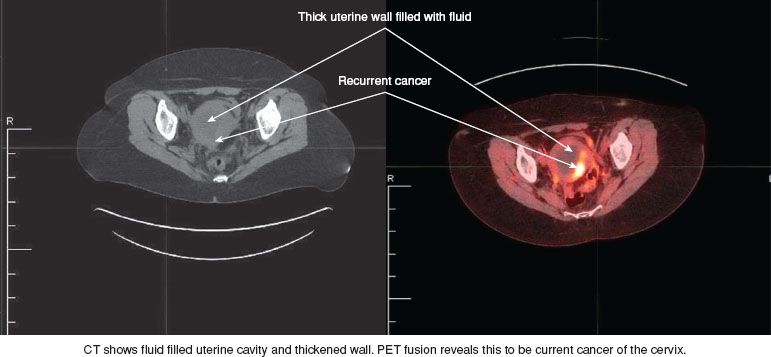

The PET/CT scan is an important addition to the preoperative investigation of a candidate for pelvic exenteration, and should significantly decrease the number of cases that have to be abandoned because of metastatic disease discovered at the time of laparotomy. Miller et al. reported that 111 of 394 patients (28.2%) undergoing exploration at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center before the availability of the PET scan had findings that led to abandonment of the exenterative procedure (17). Reasons included peritoneal disease in 49 patients (44%), nodal metastasis in 45 (40%), parametrial fixation in 15 (13%), and hepatic or bowel involvement in 5 (4.5%). A preoperative PET-CT is presented in Figure 23.4.

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

Landoni from Italy has reported the largest series to date using paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin as neoadjuvant chemotherapy) for patients considered to be poor candidates for pelvic exenteration (18). The criteria for neoadjuvant chemotherapy were large tumor size, diffuse lateral pelvic infiltration, early recurrence within 6 months, or persistence following primary chemoradiotherapy.

Thirty-one patients were identified and compared to 30 patients who had pelvic exenteration without neoadjuvant chemotherapy. There was a 61% response rate for the patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy, but no complete responders. The neoadjuvant chemotherapy group had a mean tumor size 4.39 cm versus 2.80 cm for the primary surgical group. Lateral infiltration was found in 45% of the neoadjuvant chemotherapy group versus 20% in the primary surgical group. Despite these unfavorable clinical findings, the resection margins were positive in only 26% in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy group versus 20% in the primary surgical group. Intraoperative radiotherapy was given to 4 of 8 patients with positive margins in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy group and 6 of 6 patients in the primary surgical group. After a median follow-up of 31 months, 55% were dead of disease in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy group and none alive with disease. The primary surgical group had 50% dead of disease and 7% alive with disease. There was no significant difference in overall or disease-free survival. The neoadjuvant chemotherapy group did not have any complications related to the chemotherapy.

Figure 23.4 CT and PET scans of a 52-year-old woman who had been treated with primary chemoradiation for Stage IIB squamous cell cancer of the cervix 2 years earlier. She presented with pelvic pain, and a CT scan showed a fluid-filled mass. The cervix was not visible due to an upper vaginal stricture. A Pap smear was negative, but the PET CT suggested a central recurrence. This was subsequently confirmed histologically, and the patient underwent a total supralevator exenteration.

The results from this paper would indicate that there may be a role for neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients who have no evidence of metastatic disease on PET/CT but have large tumors with lateral extension.

Preoperative Patient Preparation

The patient must be counseled extensively concerning the seriousness of the operation. She should be prepared to spend several days in the intensive care unit and have a prolonged hospitalization of up to several weeks. She must understand that her sexual functioning will be permanently altered and that she may have one or two stomas. In addition, there can be no guarantee of cure. The most difficult subject to broach is the possibility that she may have unresectable disease and that the procedure will need to be abandoned.

A mechanical bowel preparation is usually given. The patient should have the stoma sites marked by the ostomy team, and management of the ostomies should be discussed. If the patient is severely malnourished, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) should be started in advance of surgery. Because these patients may not have significant oral caloric intake for a week or longer, postoperative TPN is commonly given.

Operative Technique

The patient is placed in the low lithotomy position using stirrups that support the hips, knees, and thighs and can be repositioned during the surgery. This position allows the operators to perform the abdominal and perineal phases of the operation simultaneously. Intermittent pneumatic compression devices are applied to the calves as prophylaxis against deep venous thrombosis. Combined epidural and general anesthesia allow the epidural to be maintained after surgery for better pain control, while keeping the patient alert and able to maintain better respiratory function.

The abdominal incision is made in the midline and should be adequate for exploration of the upper abdomen and for performing the pelvic surgery. The liver and omentum should be palpated carefully. The rest of the abdomen is explored, and the para-aortic nodes are palpated. Both the right and left para-aortic nodes may be sent for frozen-section analysis. If these are negative, the pelvic spaces are opened by dividing the round ligament at the pelvic sidewall. The prevesical, paravesical, pararectal, and presacral spaces are all developed and the ligaments are evaluated for resectability. Enlarged or suspicious pelvic lymph nodes should be removed and sent for frozen-section evaluation. More than one positive pelvic node, positive para-aortic nodes, peritoneal breakthrough of tumor, or tumor implants in the abdomen or pelvis should lead to abandonment of the operation.

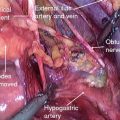

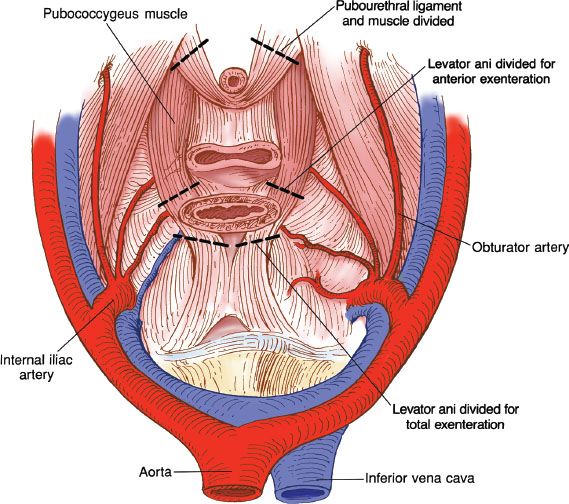

The procedure begins by ligating the internal iliac artery just after it crosses the internal iliac vein. This sacrifices the uterine artery, vesical artery, and obliterated umbilical artery. The remainder of the hypogastric artery is left intact. It carries the internal pudendal and inferior hemorrhoidal arteries that are important in maintaining the blood supply to the anal canal and lower rectum, where a potential low rectal anastomosis may be performed. The obturator artery should also be preserved because it is the major blood supply to the gracilis muscle, and a gracilis neovagina may be planned. The cardinal ligaments are divided at the sidewall and the broad attachments of the rectum to the sacrum are divided. The vaginal attachments to the tendinous arch are divided. The vaginal arteries and vein are located at the lateral margin of this pedicle. The specimen is completely mobilized and the penetration of the rectum and vagina through the pubococcygeal muscle can be identified. Various sites for ligation of pubococcygeal muscle for total exenteration versus anterior exenteration are identified (Fig. 23.5).

Figure 23.5 Cross-sectional diagram of pelvis showing lines of excision through the pubococcygeus muscle for anterior and total exenterations.

Anterior Exenteration

Anterior exenteration may be planned for lesions confined to the cervix and the anterior upper vagina. The uterus, cervix, bladder, urethra, and anterior vagina are removed, and the posterior vagina and rectum are preserved. Intraoperative bimanual palpation helps select the appropriate patient. The peritoneal reflection of the cul-de-sac can be incised and the rectum dropped away with a finger in the rectum and a finger in the vagina to ensure that the tumor is adequately resected. One surgeon conducts the perineal phase and the other surgeon conducts the abdominal phase.

The perineal incision includes the urethral meatus and the anterior vagina. A long curved clamp is placed beneath the pubis and directed caudad and anterior to the urethra. Another clamp is placed lateral to the pubourethral ligaments and directed out under the symphysis pubis, first at 2 o’clock and then at 10 o’clock. This isolates the right and left pubourethral ligaments, which can be clamped, divided, and ligated. The posterior vaginal incision is made under direct vision from below, insuring a surgical margin of at least 4 cm. The specimen is then ready to be removed. Hemostasis is provided by suture ligatures, and a pelvic pack is placed while the urinary diversion is performed. The omentum is mobilized and brought down the left paracolic gutter into the pelvis. It is used to cover the denuded area of the rectum and may provide a receptacle for neovaginal construction by a split-thickness skin graft. The omentum is sewn to the posterior vaginal epithelium, over the rectum and to the pelvic sidewalls. The skin is harvested and placed around a sterile mold, which is then placed into the cylinder formed by the omentum. If there is not enough omentum, the bulbocavernosus flaps may be used (19).

Supralevator Total Exenteration

Supralevator total exenteration with low rectal anastomosis for patients whose disease extends off the cervix on to the posterior vagina should have the segment of rectum removed en bloc with the specimen. This usually entails resection of the rectum to within 6 cm of the anal verge (Fig. 23.3). To remove the specimen, it is best to divide the sigmoid with the stapler to allow for easier exposure to the presacral space. The space is developed in the median avascular plane down to where the rectum exits between the levator muscles. The superior rectal and middle rectal arteries are sacrificed. The incision in the vaginal mucosa is 1 to 2 cm inside the hymenal ring. The supralevator attachments of the bladder, urethra, and vagina are divided, leaving the specimen attached only by the rectum. The hand is placed to encircle the rectum and traction is placed cephalad. The thoracoabdominal stapling device is then placed across the lower rectum with a 4-cm margin and the specimen is removed from the field. Preservation of some of the lower rectum is desirable for the patient to have better continence and stool storage functions. Hemostasis is provided and a pack is placed while the urinary diversion is performed. The left colon is mobilized, sacrificing the sigmoidal arteries and leaving the inferior mesenteric vessels. The sigmoid is used for a colonic J-pouch, and a low anastomosis is performed using the stapling device. The omentum should be mobilized and brought down to reinforce the stapled anastomosis. It also helps to cover the denuded area in the pelvis.

Because there is more of the vagina removed in this operation than in the anterior exenteration, the omentum may not be satisfactory for a split-thickness skin-grafted neovagina. The patient is more likely to require a myocutaneous graft from the gracilis muscles in the medial thighs or the rectus abdominis muscle. Because of the smaller opening in the vaginal introitus, the rectus abdominis myocutaneous graft is preferred.

Total Exenteration with Perineal Phase

If the tumor has extended down the lower vagina and involved the levator muscles, it is necessary to remove them for a chance of cure. The specimen is mobilized from above in a way similar to that described in the preceding operations (Fig. 23.6). The perineal incision is made around the anus and as far lateral as necessary to gain clearance from the tumor. The anococcygeal and pubococcygeal muscles are divided as necessary for margins. This leaves a large pelvic and perineal defect, which may be filled with bilateral gracilis myocutaneous flaps. Alternatively, the rectus abdominis muscle can be used. The omentum is harvested and used as a pedicle flap to provide additional blood supply and a barrier to bowel adhesions. A permanent colostomy is placed and urinary diversion is undertaken.

Figure 23.6 A surgically removed specimen from a total pelvic exenteration. Note the bladder above with a fistulous tract to the vagina, and the rectum below.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree