of WHO guided and sponsored consensus meeting in 2002 in Lyon, France that involved a group of urologic pathologists who met to discuss and finalize the new “Blue Book” on the pathology and genetics of tumors of the urinary system. The 1998 classification of WHO and the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) (15) was accepted with few changes and few dissenting votes and now has become the 2003 WHO classification of urothelial tumors (16).

TABLE 16.1 THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION/INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF UROLOGICAL PATHOLOGY CONSENSUS CLASSIFICATION OF UROTHELIAL (TRANSITIONAL CELL) NEOPLASMS OF THE URINARY BLADDER | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

papillary or invasive carcinoma, where it has been reported in as many as 90% of cases (17,18,19,20,21); or in patients with a history of prior tumors. A substantial proportion of patients with CIS alone are asymptomatic. Symptoms, when they appear, suggest cystitis: dysuria, frequency, and nocturia (19,20,22,23,24,25,26,27). Gross hematuria, usually associated with tumor, is rare; however, most patients with CIS do have microscopic hematuria. Cystoscopically, the mucosa appears to be inflamed, with an erythematous, velvety, or cobblestone appearance. It differs from banal cystitis only by its discrete gross boundaries compared with the diffuseness of cystitis. The epithelium in areas of CIS is only loosely cohesive, cells readily desquamate, and the epithelium has a rapid turnover rate. Thus, there is extensive exfoliation from even limited areas of CIS and it is common for biopsied areas of CIS to exhibit a predominantly denuded bladder wall (so-called erosive cystitis), making urine cytology a very important and sensitive means to establish the correct diagnosis. Although some patients may have only a limited focus of CIS, the majority will have multifocal or diffuse involvement.

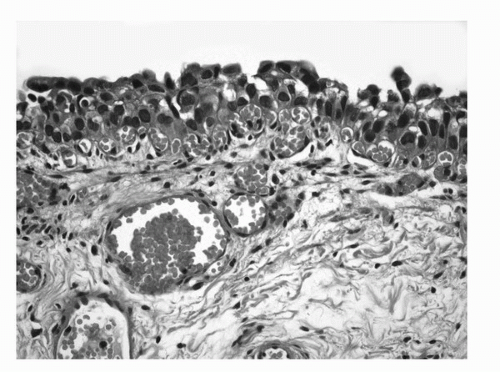

FIGURE 16.1. Urothelial Carcinoma in situ. Markedly hyperchromatic and pleomorphic cells lacking polarity in relation to the basement membrane. (See color insert.) |

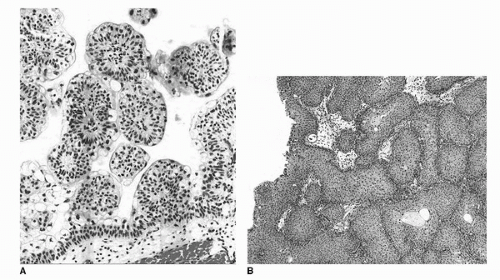

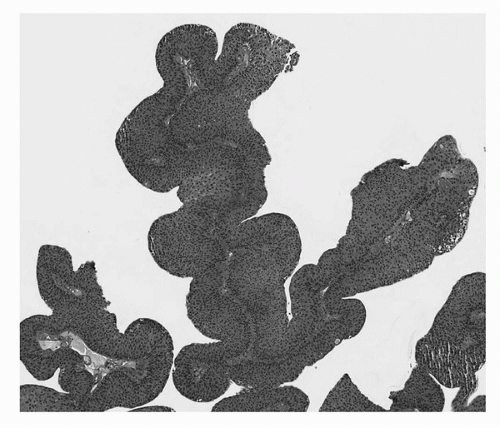

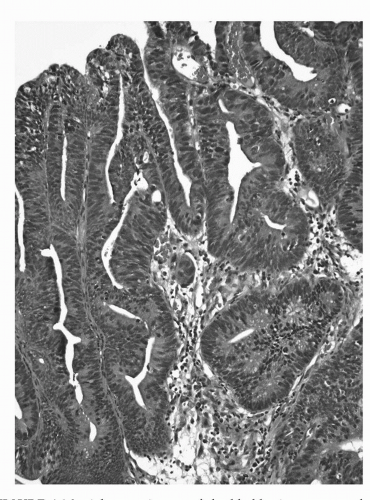

FIGURE 16.2. Urothelial papilloma (A) discrete, exophytic papillary growth. The lining urothelium is of normal thickness and cytology. Inverted urothelial papilloma (B). Invaginated fronds of histologically benign urothelium occupy the lamina propria, giving the overlying mucosa a polypoid or nodular appearance. (See color insert.) |

irrespective of cell thickness (Fig. 16.3). Mitoses are infrequent and usually limited to the basal layer. When strictly defined, PUNLMP is not associated with invasion or metastasis. Nevertheless, these patients are at risk of developing new bladder tumors (recurrence), usually of similar histology. Occasionally (7%-10%), these subsequent lesions manifest as urothelial carcinoma, such that follow-up of the patient is warranted.

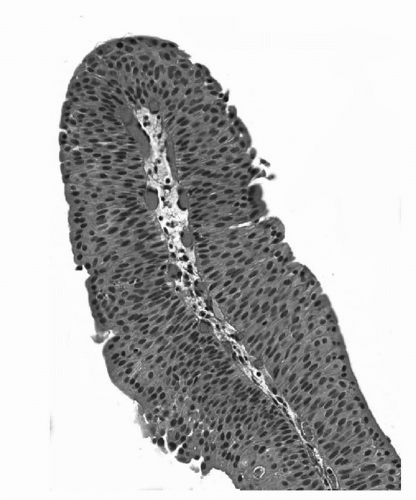

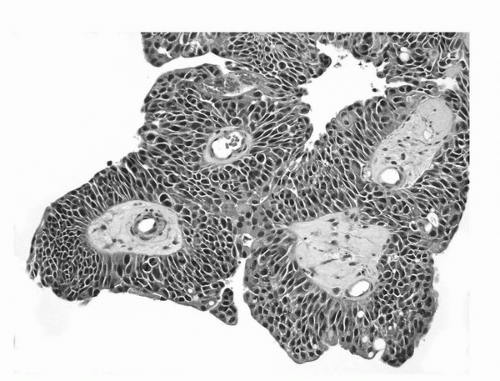

FIGURE 16.3. Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUNLMP). Papillary fronds lined by variably thickened urothelium surrounding a fibrovascular core. Cytologically the cells are arranged in an orderly fashion and lack cytologic atypia or pleomorphism. The chromatin pattern is homogeneous. (See color insert.) |

FIGURE 16.4. Noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma, low grade. Tumor cells exhibit mild pleomorphism and architectural disorder. (See color insert.) |

nests of cells with moderate to abundant cytoplasm and large hyperchromatic nuclei. Nuclear pleomorphism is common with irregular nuclear contours, occasionally prominent nucleoli, and readily identifiable mitotic figures. There is, however, some confusion related to the use of some terminology such as applying the term “muscle invasion” without further qualification. This term does not distinguish between invasion of the muscularis mucosae or the muscularis propria. Also, the term “superficial bladder cancer” should not be used as it groups three biologically different lesions: CIS, noninvasive papillary neoplasia, and carcinoma with lamina propria invasion.

FIGURE 16.5. Noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma, high grade. Neoplastic cells with marked pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, and disorder. (See color insert.) |

TABLE 16.2 MORPHOLOGIC CRITERIA TO DETERMINE INVASION INTO LAMINA PROPRIA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

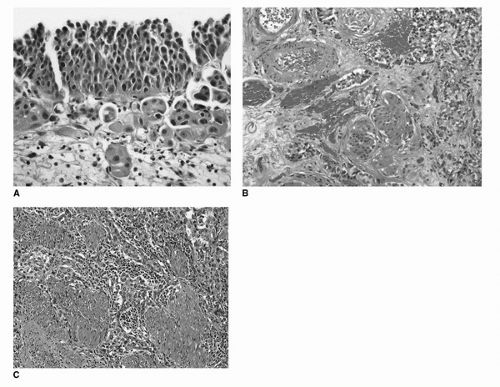

FIGURE 16.6. Invasive urothelial carcinoma. Invasion into lamina propria (A). Irregular clusters of tumor cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Tissue retraction causing peritumoral clearing is evident. Invasion into deep lamina propria (B). Irregular tumor nests surrounding muscularis mucosae and large vessels of the deep lamina propria. Invasion into muscularis propria (C). Tumor nests and cells infiltrating thick bundles of smooth muscle of the muscularis propria. (See color insert.) |

well-delineated muscularis mucosae or large vessels are readily identified in the deep lamina propria and which serve as anatomical landmarks to assess the depth of invasion (Fig. 16.6B). However, more work is necessary to arrive at criteria that can be universally adopted and applied to all transurethral resection and biopsy specimens.

TABLE 16.3 CLASSIFICATION OF UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA AND VARIANTS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

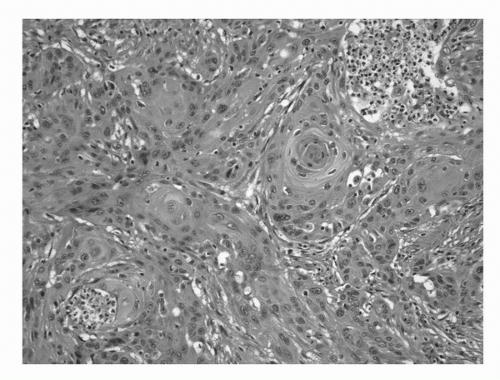

FIGURE 16.7. Squamous cell carcinoma. An invasive high-grade carcinoma exhibiting predominant squamous differentiation. (See color insert.) |

FIGURE 16.8. Adenocarcinoma of the bladder in a transurethral resection specimen. The morphologic features of this lesion overlap with those seen in colorectal adenocarcinoma. (See color insert.) |

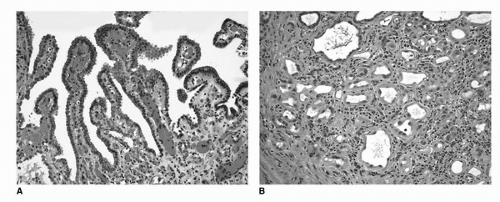

(Fig. 16.11). This lesion is usually fairly well circumscribed and does not extend into the muscularis propria and the tubules are often surrounded by a thickened and hyalinized basement membrane. Usually, there is no stromal response to the lesion, but variable amount of acute and chronic inflammatory cells is commonly encountered. Nephrogenic adenoma is thought to be due to an inflammatory insult or local injury (75,76,77). It is most commonly seen in the bladder but may occur in the prostatic urethra as well (74,77).

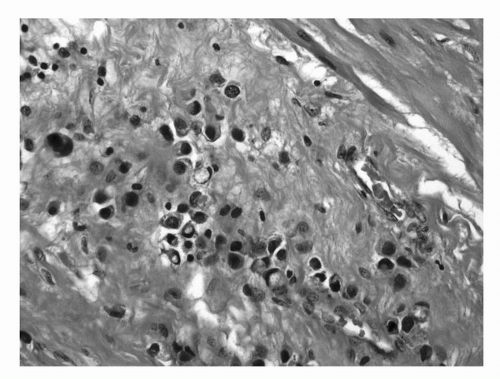

FIGURE 16.9. Signet ring cell carcinoma of the bladder. The tumor is deeply infiltrative into perivesical tissue in a diffuse pattern. Some tumor cells exhibit plasmacytoid morphology. (See color insert.) |

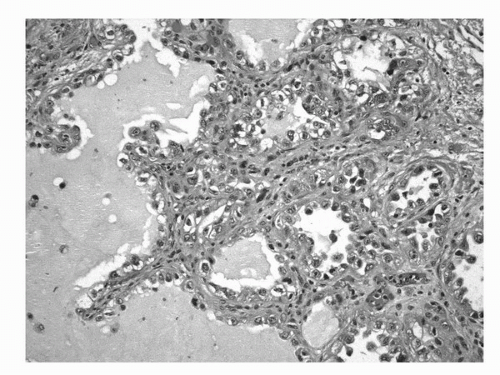

FIGURE 16.10. Clear cell adenocarcinoma. Characteristic tumor cells forming ductular, tubular, or papillary structures. Tumor cells may have clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm and hobnail appearance. (See color insert.) |

FIGURE 16.11. Nephrogenic adenoma (metaplasia). The lesion consists of bland epithelial cells in a simple papillary formation on the surface (A) and tubular structures in the submucosa (B). In the background, vascular congestion and mixed inflammatory infiltrate is evident. (See color insert.) |

direct extension from an adjacent organ has been ruled out. Once again, the urologist is in the best position to make this determination.

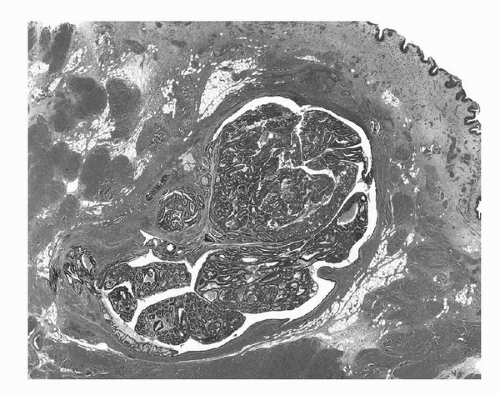

FIGURE 16.12. Urachal carcinoma. Tumor arising within and distending a urachal remnant. The tumor is an adenocarcinoma, enteric type with adjacent adenomatous change. (See color insert.) |

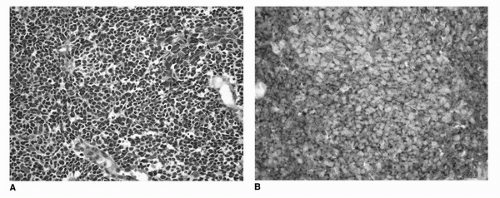

FIGURE 16.13. Small cell/neuroendocrine carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Histologic features are similar to small cell carcinoma of the lung and other sites. Tumor cells are with nuclear molding, scant cytoplasm, and dark nuclei (A). Expression of neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin (B) and chromogranin by immunohistochemistry is a consistent finding and can be helpful in establishing the diagnosis. (See color insert.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|