MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Considerations

Assessing Surgical Resectability

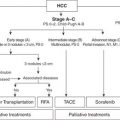

Although the TNM classification is used for pathologic staging and clinical description, the crucial step for the surgeon in the preoperative workup of PDAC patients is to determine operability—an option available to fewer than a quarter of all patients at diagnosis. PDAC of the pancreatic head, neck, or uncinate process is stratified into the following: (a) resectable, defined as no radiographic evidence of extrapancreatic disease, a patent SMV–PV confluence, and no evidence of tumor extension to the celiac axis or SMA; (b) borderline resectable, defined as nonmetastatic tumor with SMA abutment (≤180 degrees), abutment or encasement of the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) up to or around a short, reconstructable segment of the common hepatic artery (CHA), or complete occlusion of the SMV–PV confluence, with suitable, uninvolved vein above and below to allow venous reconstruction (as a general rule, tumors encasing up to 2 cm of the SMV and/or PV for up to a 180-degree circumference are considered technically possible); (c) locally advanced, defined as encasement (>180 degrees) of the celiac axis or SMA or occlusion of SMV–PV confluence without an option for venous resection and reconstruction; and (d) metastatic, defined as distant metastatic spread to the liver, peritoneum, or rarely the lung. It is important to realize that, for this disease, operability ≠ resectability. Up to 85% (but certainly not 100%) of radiographically amenable lesions are resectable intraoperatively, whereas fewer than 20% of locally advanced lesions are ultimately amenable to resection.

Role of Diagnostic Laparoscopy

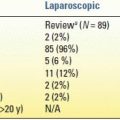

The use of diagnostic laparoscopy in PDAC staging remains controversial. Although the combination of laparoscopy with laparoscopic ultrasound can improve the accuracy of determining peritoneal and/or hepatic dissemination to almost 98%, we do not recommend the routine application of diagnostic laparoscopy in PDAC due to its questionable cost-effectiveness as well as the impressive accuracy of modern high-fidelity axial imaging. Moreover, even in potentially unresectable disease, laparoscopy is unnecessary if the patient were to benefit most from surgical palliation (see below). Alternatively, a more selective use of diagnostic laparoscopy is justified in those patients with a high risk of occult metastatic disease in whom nonsurgical palliation would be durable. This scenario includes the following: (a) lesions in the pancreatic body or tail; (b) larger (> 3 cm) primary tumors; (c) equivocal radiographic findings suggestive of occult metastasis such as low-volume ascites, peritoneal carcinomatosis, or small hepatic lesions not amenable to percutaneous biopsy; and (d) markedly elevated CA 19-9 or hypoalbuminemia suggestive of advanced disease. In addition, diagnostic laparoscopy may be considered in certain cases of borderline resectable and/or locally advanced disease—understanding that evidence of metastatic spread might alter whether radiation therapy would be used in conjunction with chemotherapy.

Role of Preoperative Biliary Drainage for Obstructive Jaundice

In the past, a majority of patients with resectable PDAC who presented with obstructive jaundice underwent either endoscopic or percutaneous transhepatic preoperative biliary drainage (PBD) before surgical referral. Recently, however, the routine use of PBD in resectable PDAC has been discouraged in the light of convincing evidence that PBD increases the rate of postoperative complications and offers little benefit compared with early surgery for resectable tumors. In a recent randomized multicenter trial, van der Gaag et al. showed that PBD was associated with significantly higher rates of serious perioperative complications compared with early surgery, while mortality and length of hospital stay did not differ significantly between the groups. However, the role of biliary drainage as temporary palliation in patients with borderline resectable tumors undergoing neoadjuvant therapy is clinically relevant. In such situations, authorities advocate the use of self-expandable metal stents over plastic stents given their improved durability should the tumor be ultimately deemed unresectable.

Role of Neoadjuvant Therapy for PDAC

There is growing enthusiasm for the use of neoadjuvant chemoradiation in PDAC that relies on the following theoretical principles: (a) increased efficacy of chemoradiation in well-oxygenated tissue not devascularized by surgery; (b) potential for downstaging, thereby improving R0 resection and decreasing locoregional recurrence rates; and (c) identifying patients with rapidly progressive disease who might not derive a survival advantage from surgery. Several groups have utilized neoadjuvant regimens involving gemcitabine, 5-FU, or paclitaxel plus radiation for resectable PDAC. Current data suggest that while neoadjuvant chemotherapy is well tolerated and does not delay surgical intervention, there is no clear survival benefit to this strategy compared with standard postoperative adjuvant therapy. A 2009 AHPBA-SSO-SSAT consensus panel indicated that neoadjuvant therapy for resectable PDAC should be considered investigational and offered within the context of clinical trials or multidisciplinary treatment programs.

However, there may be an emerging role for neoadjuvant strategies in borderline resectable tumors. Investigators from the University of Virginia demonstrated that 46% of patients with borderline resectable PDAC underwent surgical resection after completing neoadjuvant capecitabine-based chemoradiation. This group had favorable overall survival (OS)—median 23 months—similar to that of a historical cohort of patients with resectable PDAC. In a recent report from the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, 66% of borderline resectable PDAC patients underwent resection after neoadjuvant therapy (chemoradiation alone or gemcitabine-based chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation), of which an R0 resection was achieved in 95%. Median OS in this cohort was up to 33 months following their uniquely highly standardized protocol. These data solidify the role for induction therapy in borderline resectable PDAC, with attempted resection offered to patients without evidence of cancer progression on presurgical restaging studies. Several challenges remain: (a) adherence to and application of the consensus definition of “borderline resectable” tumors across institutions; (b) what the most effective neoadjuvant modality is (chemotherapy alone, chemoradiation, or a combination); and (c) need for a multi-institutional trial to validate these optimistic early reports. As is the case for resectable tumors, it remains a fact that there has been no direct clinical comparison of the two techniques that would clearly advocate one over the other.

Surgical Resection and Related Controversies

Resection of PDAC can be broadly categorized into two types: (i) pancreaticoduodenectomy for tumors situated in the head, neck, or uncinate process or (ii) distal pancreatectomy for tumors of the body and tail. While technical details of these operations can be found in Chapter 7 by Pilgrim et al., a discussion of the global conduct of these operations and select lingering controversies in the operative management of PDAC follows.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple Procedure)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree