Abstract

Paget disease (PD) is defined as the presence of neoplastic cells of glandular differentiation, interspersed between keratinocytes of nipple epidermis, and constitutes approximately 1% of breast cancer cases. More than 90% of cases are associated with an underlying in situ or invasive breast carcinoma. The most accepted explanation for the development of PD is that it results from the migration of cells from the underlying tumor via the duct system into the epidermis, the so-called epidermotropic theory. Migration may be mediated by keratinocyte-secreted heregulin-α through its binding to HER3 or HER4 receptors, dimerized to highly overexpressed HER2. The approximately 10% of cases of PD not associated with an underlying breast cancer may result from neoplastic transformation of Toker cells, benign cells with glandular phenotype frequently located in the normal nipple epidermis. The differential diagnosis of PD includes other eczematous conditions of the nipple, but any unilateral nipple abnormality in an adult woman should be considered malignant until proven otherwise. Pathologically, the differential diagnosis includes other neoplastic entities associated with atypical cells in the epidermis, as well as benign mimics. Up to two-thirds of patients presenting with PD without a palpable breast mass have a normal mammogram. Magnetic resonance imaging is recommended in cases with no findings on clinical examination, mammogram, or ultrasound. Despite data suggesting that breast conserving surgery plus radiotherapy is effective in treating PD, mastectomy continues to be the most popular treatment. Review of published data suggests a significant bias to perform mastectomy in PD, even in the presence of tumors that would likely be managed with breast conservation had they not presented with PD. Sentinel lymph node surgery is appropriate in PD patients with a clinically negative axilla and should be used in accordance with guidelines established for usual breast cancer.

Keywords

Paget disease, nipple diseases, Paget cells, Toker cells, invasive Paget disease, breast cancer, HER2

Paget disease (PD) is histologically defined as the presence of neoplastic cells of glandular differentiation, interspersed between keratinocytes of nipple epidermis, and most often presents as an eczema-like nipple lesion. More than 90% of cases are associated with an underlying in situ or invasive breast carcinoma, detected before, simultaneously with, or after the diagnosis of PD.

Sir James Paget, who described the condition in 1874, considered it a preneoplastic or paraneoplastic process preceding the appearance of breast carcinoma. It was not until 1904 that Jacobaeus described the histopathology of PD and proposed that it represented spread of carcinoma cells into the epidermis of the nipple from an underlying preexisting neoplasm. This is today the most accepted theory regarding its pathogenesis.

PD constitutes approximately 1% of the cases of breast carcinoma diagnosed in the United States. According to published data from Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry of the National Cancer Institute, despite an increase of 10% in the incidence of both invasive and in situ ductal carcinomas of the breast during 1988 to 2002, the incidence of PD decreased by 45% in the same period of time. Eighty-six percent of cases were associated with an underlying invasive or in situ carcinoma. The median patient age at presentation was 62 years according to the SEER registry, 70 in a Scandinavian study, and 48.1 in a large Chinese series.

Pathogenesis

The most accepted explanation for the development of PD is that the neoplastic cells (commonly referred to as Paget cells ) result from the migration of cells from the underlying adenocarcinoma through the duct system, and into the epidermis, the so-called epidermotropic theory. This theory is supported by the existence of an underlying carcinoma in about 90% of cases of PD, which usually shares phenotypic similarities with Paget cells. Further support for this theory comes from the reported decrease in incidence of PD despite an increase in breast cancer incidence, suggesting that the former is a result of earlier detection of tumors at a point before the spread of malignant cells into the epidermis. The occurrence of secondary PD also supports an epidermotropic mechanism for this phenomenon. In these cases, PD is seen surrounding an area in the skin that has been directly invaded by a tumor, not necessarily in the proximity of the nipple, suggesting a tumoral origin of the Paget cells. A molecular mechanism has been proposed to explain the migration capabilities of Paget cells. According to this model, heregulin-α is produced by keratinocytes, as demonstrated by the presence of heregulin-α messenger RNA in skin keratinocytes. This factor induces spreading, motility and chemotaxis of cultured breast cancer cells, a phenomenon likely mediated through its binding to HER3 or HER4 receptors, which in turn are dimerized to highly overexpressed HER2. Migration capability of cultured cells was inhibited when they were previously exposed to monoclonal antibody AB2 directed against the extracellular domain of HER2. Vimentin expression in breast cancer cell lines has also been associated with increased motility and invasiveness in vitro. In one study, vimentin expression was found in 44.7% of cases of mammary PD, suggesting a potential role of this intermediate filament in cell motility and migration. p16, a molecule involved in cell motility, is expressed at similar levels in PD and in underlying ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), suggesting a role for this molecule in the intraepithelial spread of Paget cells.

Approximately 10% of cases of PD are not associated with an underlying breast cancer. Some of these cases may represent an undetected breast tumor, resulting from failure to detect a small occult breast cancer in a large, albeit well-sectioned, surgical specimen due to practical limitations (cost and time). However, some data suggest the possibility of a primary neoplastic process localized in the nipple-areola complex epithelium. For example, some studies have shown genotypic differences between Paget cells and underlying carcinoma cells, whereas others have shown that some cases of PD associated with underlying DCIS contain substantial areas of normal-appearing ducts between the two neoplastic processes (i.e., skipped areas). These findings have prompted an alternative explanation of PD histogenesis, which is commonly referred to as the intraepidermal transformation theory. This hypothesis maintains that Paget cells arise in situ from transformation of multipotential cells in the epidermis or from the terminal portion of the lactiferous duct at its junction with the epidermis. The occurrence of extramammary PD (i.e., presence of similar histologic findings in other sites of the body) gives further support to this theory, particularly because extramammary PD is much less often associated with an underlying malignancy. At the core of this theory are Toker cells, which are considered by some as precursors of PD. Toker cells are inconspicuous clear cells that are predominantly located in the skin of the nipple-areola complex. They are detected in 10% of nipples with routine histology, but in up to 83% of cases when immunohistochemical stains are used, distributed in a dispersed fashion within the epidermis, mainly as scattered individual cells. Their cytomorphologic features are bland, without suggestion of malignancy ( Fig. 12.1 ). Ultrastructurally, Toker cells are globoid with dendritic cytoplasmic projections and are distinct from surrounding keratinocytes, Langerhans cells, melanocytes, and Merkel cells. Toker cells are immunophenotypically similar to Paget cells in sharing expression of cytokeratin 7 and CAM 5.2 but lack high molecular weight cytokeratin, S100, and HMB45 expression. They differ in the negative expression of mucin, CD138, HER2, and epithelial membrane antigen. They are consistently negative for estrogen receptors (ER) and progesterone receptors (PR). Whether Toker cells are the result of upward migration of ductal cells into the epidermis, are of sebaceous gland apparatus origin, or develop through an in situ transformation of keratinocytes is still unresolved. Independently of the origin, the similarities between Toker and Paget cells have suggested that the former may represent the cell that undergoes malignant transformation in the initial phases of PD. A case report of PD confined to the areola associated with multifocal Toker cell hyperplasia suggests that indeed Toker cells play a significant role in the pathogenesis of PD. Yet some authors have suggested that Paget cells derive directly from altered keratinocytes, a theory supported by the finding of desmosomes between Paget cells and adjacent keratinocytes. The referenced study from Chen and colleagues demonstrated that despite steadily decreasing incidence rates of PD with an underlying tumor between 1988 and 2002, the incidence rates of PD without an underlying tumor remained unchanged. These data suggest that although a majority of cases of PD represent epidermotropic extension of preexisting underlying breast tumor cells, a smaller proportion without an underlying malignancy may arise from intraepidermal transformation of Toker cells or keratinocytes.

Histopathology

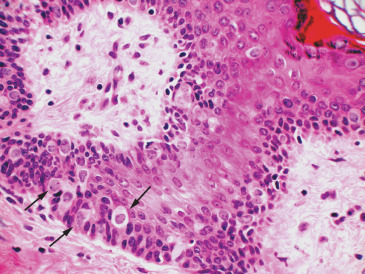

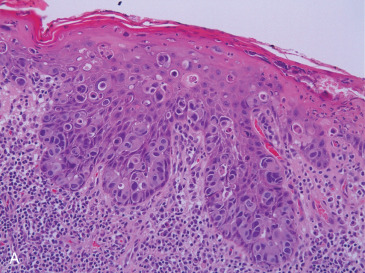

The hallmark of PD is the presence of neoplastic cells with abundant clear or pale cytoplasm, situated individually or in small clusters between native epidermal keratinocytes ( Fig. 12.2A ). These cells can be present in any layer of the epidermis, being usually more numerous in the basal and lower spinous strata and can form intraepidermal aggregates and even glandular structures. Usually larger than the surrounding keratinocytes, PD cells are pleomorphic, display prominent nucleoli and frequent mitoses, and show intracytoplasmic mucin-filled vacuoles in up to 25% to 50% of cases, which are highlighted with a periodic acid–Schiff or mucicarmine stain. The epidermis can show hyperkeratosis with parakeratosis, hyperplasia with papillomatosis, or ulceration with crusting. The underlying dermis usually shows reactive changes, including a prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and hypervascularity.

Paget cells may often be identified in the underlying lactiferous ducts, sometimes merging unperceptively with underlying DCIS, which is more often high nuclear grade, solid, or comedo type. Association with lobular carcinoma in situ has been reported, although it is extremely rare. In these cases, bilateral PD may be present.

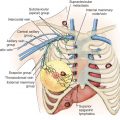

When an underlying invasive carcinoma is present, it is usually of ductal type and high histologic grade. Most often it is located in the central portion of the breast, occasionally abutting the dermis, as terminal lobular units have been described within the nipple in approximately 25% of entirely examined nipples. Relatively distant quadrant peripheral tumors can be seen connected to the PD through ducts involved by DCIS. Multifocality is not uncommon.

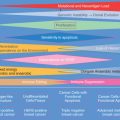

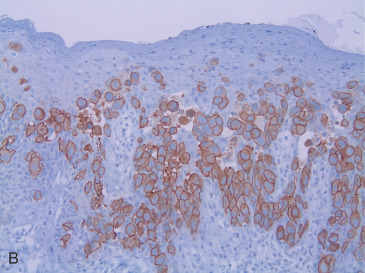

Paget cells are usually positive for markers of breast epithelium differentiation. As opposed to the surrounding keratinocytes, Paget cells are frequently positive for cytokeratin 7, CAM 5.2, and other low molecular weight cytokeratins, and negative for high-molecular weight cytokeratins. They usually show expression of MUC1, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen and occasionally gross fluid cystic disease protein. The vast majority of cases will show strong overexpression of the HER2 protein and amplification of the gene ( Fig. 12.2B ). This would also explain the relatively low frequency of ER or PR expression in PD. Sek and associates demonstrated a HER2 overexpressing molecular subtype, characterized by HER2-positive, ER-negative immunophenotype, in 86% of cases of PD, whereas “luminal B” (ER-positive, HER2-positive) and “luminal A” (ER-positive, HER2-negative) subtypes represented 12% and 2% of cases, respectively. The underlying in situ or invasive tumors demonstrated a similar distribution of subtypes. Lester and colleagues found different molecular subtypes depending on whether the PD was associated with underlying DCIS (most commonly HER2 overexpressing subtype) or with invasive carcinoma (most commonly luminal B). Up to 18% of Paget cells express S100 protein, in keeping with the occasional expression of this marker by breast carcinomas. However, contrary to cells of melanoma in situ, Melan-A is consistently negative.

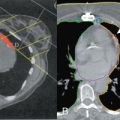

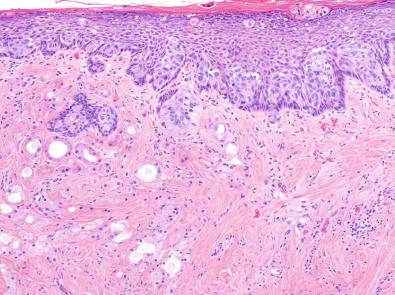

On rare occasions, the intraepithelial cells of PD invade into the underlying dermis, a variant commonly referred to as “invasive PD” ( Fig. 12.3 ). This phenomenon has been described in cases of PD associated with an underlying invasive breast tumor, with an in situ carcinoma only, or with no underlying breast neoplasm. It is thought to represent a later event in the progression of PD, in which Paget cells acquire invasive capabilities. Reported incidence of this phenomenon ranges from 4% to 11% of cases of PD. The dermal invasive component is usually small, and by definition, should be distinctively separate from any invasive tumor that may exist in the breast parenchyma. Mean depth of invasion and mean diameter were reported as 0.637 and 1.268 mm, respectively, in the largest series published to date. In this study, no significant difference in prognosis was found between cases with invasive and noninvasive PD. However, lymph node metastases have been reported in cases of invasive PD in the absence of an invasive breast carcinoma. Accurate recognition of this variant should avoid overstaging tumors by confusing it with skin involvement (pT4b disease) or tumor satellitosis.

The histopathologic differential diagnosis of PD includes conditions that may display intraepidermal clear or pale cells, which appear morphologically distinct from surrounding keratinocytes, a histologic picture also known as a “pagetoid” pattern. These include nonneoplastic conditions, benign pathologic processes, and other malignancies ( Table 12.1 ).

| Cytokeratin 7 | CAM 5.2 | HMWCK | S100 | Melan A | HER2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paget disease | +++ | +++ | – | +/– | – | +++ |

| Toker cells | +++ | +++ | – | – | – | – |

| Malignant melanoma | – | – | – | +++ | +++ | – |

| Squamous cell carcinoma in situ | –/focally + | – | +++ | – | – | – |

Keratinocytes with accumulated glycogen within their cytoplasm, giving them the appearance of clear cells interspersed within more classic keratinocytes, are frequently seen in nipple epidermis. These cells usually show a pycnotic angulated nucleus, and the surrounding cytoplasm appears empty on routine histology. They are predominantly located in the midepidermis. Some authors consider them to be reactive in nature and refer to them as pagetoid dyskeratosis cells ; in contrast with Paget cells, pagetoid dyskeratosis cells share with epidermal keratinocytes expression of high molecular weight keratins. Toker cells, as described earlier, are benign clear cells seen normally in the nipple epidermis. As discussed, they are immunoreactive with cytokeratin 7 and likely represent benign ductal cells extending into the epidermis. Toker cells differ from Paget cells in that they do not show cytologic features of malignancy and are consistently negative for HER2 and epithelial membrane antigen.

Nipple adenoma is part of the differential diagnosis not only because it may clinically present as an eczematous lesion, but also because it is usually associated with Toker cell hyperplasia, mimicking PD. Nipple adenomas are localized lesions characterized by an adenomatous proliferation of ducts and tubules, associated with florid epithelial and myoepithelial cell hyperplasia, usually within a desmoplastic stroma. The architectural complexity of the lesion may be confused with invasive or in situ carcinoma, leading to the erroneous interpretation of the associated Toker cell hyperplasia as PD. If in doubt, a HER2 stain can help in determining the exact nature of these cells.

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCCIS), or Bowen disease, rarely involves the nipple but can present with a pagetoid pattern, with isolated, clustered, and sheets of pale or clear atypical keratinocytes dispersed in the epidermis, usually on a background of more mature-appearing atypical keratinocytes. Contrary to Paget cells, the atypical pagetoid keratinocytes can show single cell keratinization, intercellular bridges and cytoplasmic keratohyalin granules. Frequently, other areas of the tumor will exhibit classic SCCIS. In difficult cases, immunophenotyping often resolves the issue, as the atypical keratinocytes usually are cytokeratin 7 and CAM 5.2 negative, and express high molecular weight-cytokeratins. A so-called acantholytic anaplastic variant of PD may be particularly difficult to differentiate from acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma. A battery of immunostains may be necessary to distinguish SCCIS from PD, because SCCIS, particularly the pagetoid variant, may express cytokeratin 7.

Malignant melanoma should be considered in both the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnoses. Paget cells frequently incorporate melanin from adjacent epidermal cells, further complicating the histologic or cytologic picture. However, primary malignant melanoma of the nipple is a rare disease that should not be diagnosed before thoroughly excluding the possibility of PD. Immunohistochemistry is helpful because Paget cells are usually Melan A negative and positive for cytokeratin 7, whereas melanoma cells would show the opposite immunophenotype. As mentioned, S100 protein is not useful in this differential diagnosis because some cases of PD may show positivity for this marker. A recent report of HMB45-positive PD should raise caution over false-positive results with this marker. Concomitant use of another melanocytic marker, such as SOX10, should minimize diagnostic difficulty.

Other diagnoses rarely in the differential algorithm of a pagetoid histologic pattern involving the nipple include clear cell papulosis, sebaceous carcinoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Adequate histologic sampling and judicious use of immunohistochemistry usually suffice to arrive to the correct diagnosis.

Clinical Presentation

PD characteristically presents as an eczema- or psoriasis-like lesion of the nipple. In advanced cases, adjacent areola and surrounding skin may also be involved ( Fig. 12.4 ). The latter finding is present in 25% to 98% of cases, depending on the series. Rare cases of extensive skin involvement, including spread beyond the breast to chest wall skin, have been reported. PD also may present with nipple scaling, erythema, ulceration, hyperkeratosis, hyperpigmentation, induration, bloody discharge, crust, inversion, or distortion. New-onset nipple inversion can be present in up to 20% of cases, and nipple discharge has been reported in up to 36% of patients. Symptoms are common, particularly nipple pruritus, pain, or burning sensation. PD may represent tumor persistence or recurrence in patients with breast cancer treated with nipple-sparing mastectomy. Rare cases may center in the axilla, associated with underlying accessory mammary tissue. Up to 40% of cases have a palpable mass on presentation, and some patients may present with enlarged axillary lymph nodes. A case associated with surrounding ipsilateral eruptive seborrheic keratoses (Leser-Trelat sign) has been reported. One case of pigmented PD presented as unilateral enlargement of the areola. PD is reportedly asymptomatic in 22% to 67% of cases, depending on the series. In these cases, the patient usually has undergone surgery for a clinically detected breast cancer, and histologic changes of PD are found in the resection specimen. Bilateral presentation is rare ; however, PD may present several years after a contralateral breast cancer. To avoid misdiagnosis as delayed radiation dermatitis, it is important to keep in mind that initially occult PD may present with clinical abnormalities months or years after wide local excision or nipple-sparing mastectomy of ipsilateral breast carcinoma.

Although the vast majority of cases are seen in female patients, PD of the male breast is occasionally encountered. As in the female patient, PD in the male may be associated with an invasive carcinoma, an in situ breast cancer, or no underlying breast cancer. A worse prognosis has been suggested for male cases, although no large series exist that control for stage at presentation and diagnosis delay in this population.

Eczematous or other inflammatory dermatoses are necessarily in the differential diagnosis, such as atopic dermatitis, irritant or allergic contact dermatitis, and psoriasis. In contrast with PD, atopic dermatitis, and often irritant or allergic contact dermatitis, usually presents with bilateral involvement. The differential diagnosis of a scaling, eczematous, or ulcerated lesion of the nipple also includes infections, such as candidiasis, tinea corporis (dermatophyte infection), or syphilis. Various benign or malignant disorders rarely reported to present with PD-like involvement of nipple and/or areola include erosive nipple adenoma, nevoid hyperkeratosis, pemphigus vulgaris, sebaceous carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and pagetoid reticulosis–like T-cell lymphoma. Skin changes associated with nipple reconstruction and tattooing may also mimic PD.

A thorough clinical examination may be valuable in differentiating these conditions, because it may reveal systemic abnormalities or extramammary skin lesions that could orient the diagnosis. The finding of a palpable breast mass is an ominous sign that would point to the diagnosis of PD. Primary malignant melanoma of the nipple is rare, as stated, and in most reported cases, PD was a strong consideration in the differential diagnosis. PD can mimic malignant melanoma, as pigmentation of Paget cells is common.

Up to 20% of patients may have symptoms and/or signs of PD for more than a year before seeking medical attention. Various factors contribute to a sometimes profound delay in diagnosis. In particular, patients or providers may conclude that the eczema-like appearance or symptoms of pruritus are due to inflammation of the nipple and empirically recommend treatment with topical steroids, which results in transient or sustained improvement in symptoms and/or appearance of the nipple. Indeed, treatment-associated or spontaneous apparent remission—so-called healed PD —reinforces the false conclusion that the clinical abnormality is insignificant. Inflammatory dermatoses often are considered before PD, particularly when a breast abnormality is not detected by clinical examination or imaging studies. Furthermore, physicians often are reluctant to biopsy the nipple, usually due to the erroneous impression that such a seemingly minor problem must be benign, mistaken concern that a carefully performed biopsy will result in nipple disfigurement or impair potential for lactation in a premenopausal woman, or that the patient is too young to have PD (despite reports of its occurrence in women during the third decade of life). Thus timely diagnosis of PD requires a low threshold for obtaining a biopsy: any unilateral nipple abnormality in an adult woman should be considered malignant until proven otherwise.

Clinicians have several options to obtain tissue for diagnosis of PD. Wedge biopsy of the skin and underlying breast tissue renders the most diagnostic material because this excisional specimen includes a well-represented epidermis and underlying lactiferous ducts. Punch biopsy may have a lower diagnostic yield because of its smaller size and the potentially discontinuous nature of Paget cells, but is a convenient, relatively high-yield option for obtaining diagnostic tissue; the punch biopsy site usually heals with limited scarring or distortion of the nipple-areola. In addition, particularly when a larger (5- or 6-mm vs. 3- or 4-mm diameter) punch biopsy is obtained, the resultant tissue specimen may be deep enough to include a lactiferous gland containing the associated DCIS. In the absence of an imaging abnormality that suggests an abnormality deep within or below the nipple, the narrow diameter of a core needle biopsy makes sampling error with this method more likely than with even a small punch biopsy. Shave biopsies offer breadth of epidermis, but superficial shaves may produce only nondiagnostic serosanguineous keratotic crust. Even when the specimen includes full-thickness epidermis, allowing for exclusion of PD, a superficial shave biopsy is insufficient to reveal an alternative abnormality involving the dermis, such as nipple adenoma. A saucerization-type shave biopsy, which produces a broad and deep tissue specimen, is associated with substantial risk of nipple disfigurement. Scraping or imprint of the nipple surface is an accessible noninvasive method for rapid diagnosis, although data on sensitivity and specificity of the technique are limited, this method is likely unreliable because it yields even less material than superficial shave biopsies.

No single method is completely reliable for establishing a diagnosis of PD because most biopsies represent partial samples of the disorder. Any specimen may be false negative, particularly a narrow biopsy (such as a core needle or a 2- to 3-mm punch), a sample from an ulcerated or hyperkeratotic lesion, or those from symptomatic patients with limited or no visible abnormalities. In general, biopsy should be centered on the most clinically abnormal (e.g., most eczematous or indurated) portion of the nipple, except that biopsy of the edge rather than base of an ulcer is preferable because at least a portion of intact epidermis is needed for diagnosis. Additional biopsy is usually indicated when the first specimen fails to yield a specific diagnosis, and in all cases when most or all of the epidermis is absent. For such patients, particularly when clinical suspicion for PD is high and no specific diagnosis can be rendered on the initial biopsy, the second procedure should include a broader and deeper sample than the first (e.g., use of a punch rather than core needle biopsy, larger punch, or wedge incisional or excisional biopsy).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree