17119

Ovarian Cancer in the Older Woman

William P. Tew

BACKGROUND

Ovarian cancer is recognized as a disease of aging, with more than 30% of new cases being diagnosed in women older than 70 (1). The rate of older women with ovarian cancer is expected to increase as our population ages and life expectancy improves (2–4). Outcomes steadily worsen with aging: the relative survival rates at 1 year are 57% for women aged 65 to 69 years, 45% for those aged 70 to 74 years, and 33% for those aged 80 to 84 years (5). Various theories have been put forward to account for the decreased survival in older women, including: (a) more aggressive cancer biology with higher grade and more advanced stage; (b) inherent resistance to chemotherapy; (c) patient factors leading to greater toxicity with therapy such as multiple concurrent medical problems, polypharmacy, functional dependence, cognitive impairment, depression, frailty, and poor nutrition; and (d) physician and health care biases that lead to inadequate surgery, suboptimal chemotherapy, and poor enrollment in clinical trials (6). Guidelines have been developed to help inform oncologists about caring for the older adult (7).

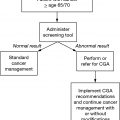

GERIATRIC ASSESSMENT

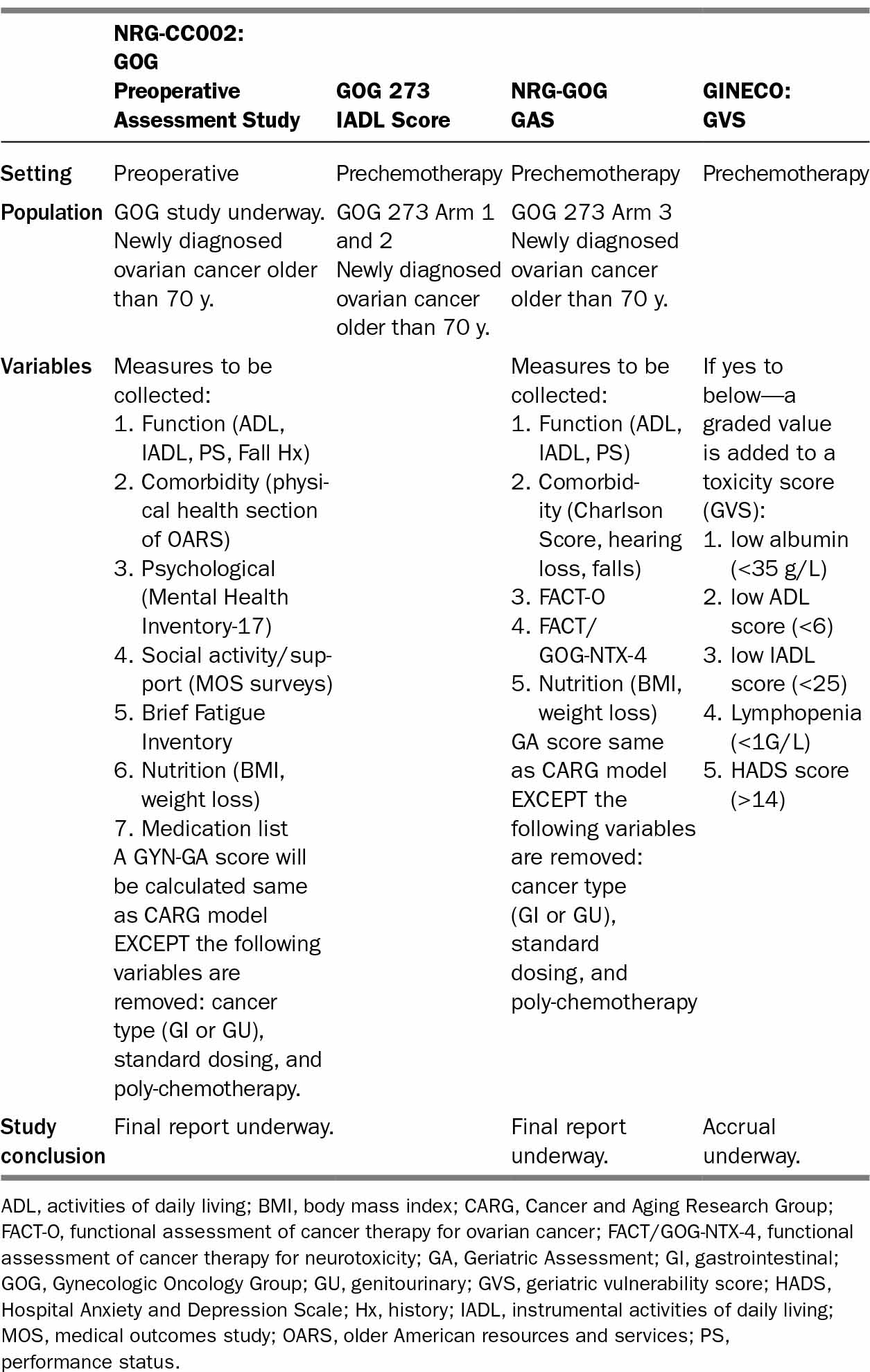

Geriatric assessment (GA) provides clinicians with information about a patient’s functional status, comorbid medical conditions, cognition, psychological status, social functioning and support, and nutritional status (refer to Chapter 13). Several studies have demonstrated the predictive value of GA for estimating the risk of severe toxicity from chemotherapy and surgery (8,9). GA instruments used specifically for women with gynecological cancer (see Table 19.1) include the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) score (9,10), Geriatric Vulnerability Scale (11), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) in GOG 273 (12), and the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) GA/Preoperative Scores. Functional assessment specifically with IADLs appears to be most predictive and is included in all the scores.

172TABLE 19.1 GA Tools Used in Clinical Trials for Older Ovarian Cancer Patients

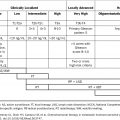

173SURGERY

Surgery plus platinum-based chemotherapy are standard treatments for women with advanced ovarian cancer. Older patients, particularly those older than 80 years, are less likely to receive any surgery at all, and those who undergo surgery develop higher surgical morbidity, achieve lower rates of optimal cytoreduction, and likely did not see a specialized gynecologic oncologist (13,14). A Surveilance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) analysis of older women who underwent primary cytoreductive surgery (CRS) (n = 4,517) showed a 30-day mortality of 5.6%. Those admitted emergently had a 30-day mortality of 20.1%. Those aged 75 and older with either stage IV disease or stage III disease and a comorbidity score of 1 or more had a 30-day mortality of 12.7% even when admitted electively (15). In addition, there is concern that toxicities of surgery may prevent older women from receiving chemotherapy. One retrospective report on 85 patients over the age of 80 undergoing CRS (mostly primary) showed that 13% died prior to discharge and 20% died within 60 days of surgery. Thirteen percent never received adjuvant therapy, and of those treated 43% completed less than three cycles of therapy (16).

These and other data on the increased toxicity of primary CRS in the elderly have led to the increased use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) and interval CRS in older patients. The ability to assess who is fit enough to undergo aggressive CRS followed by chemotherapy and who should be offered an alternative pathway such as NACT and interval CRS or primary chemotherapy alone is an unmet need. Aletti identified a high-risk group of women who do not appear to benefit from primary surgery. Risk features included stage IV disease, high initial tumor distribution, poor performance status (PS) (ASA score ≥ 3), poor nutritional status (albumin < 3.0g/dL), and older age (≤75 years) (17). Although each patient plan must be individualized, at this time it is reasonable to use these criteria as guidelines for a NACT approach. The American Society of Oncology (ASCO) and Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) jointly developed guidelines to help oncologists select patients for primary surgery versus NACT (18).

CHEMOTHERAPY

Background

First-line chemotherapy improves survival in older women with ovarian cancer. Platinum-based chemotherapy among women over 65 years was associated with a 38% improvement in survival outcomes compared with the use of no chemotherapy (18, 19). However, only half of this population received platinum-based chemotherapy. A SEER review, which included almost 8,000 women older than 65 years with stage III or IV epithelial ovarian cancer, suggested that while patients who underwent surgery only had similar survival compared with patients who received no treatment (2.2 vs. 1.7 months), patients receiving chemotherapy as the sole treatment for their disease had a better overall survival (OS) (14.4 months) (20). Those who received debulking surgery and optimal chemotherapy (six cycles within an appropriate time frame) had the best OS (39 months), an association that was maintained after multivariate analysis controlling for demographics, cancer type, and comorbidities.

174Older patients are more vulnerable to certain chemotherapy toxicities. The most common toxicities of platinum-taxane regimens, the usual first-line therapy for ovarian cancer, are cytopenias and neuropathy. This was highlighted in a large retrospective analysis of outcomes and toxicities seen in the 620 patients aged 70 years and older enrolled in GOG 182, a phase III trial studying triplet-chemotherapy regimens for patients with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer (21). Older women enrolled in this trial were likely to be healthier than the average older woman with ovarian cancer, but older patients still had poorer PS, lower completion rates of all eight chemotherapy cycles, and increased toxicities, particularly grade 3+ neutropenia and grade 2+ neuropathy (36% vs. 20% for older vs. younger women on the standard carboplatin/paclitaxel arm). Although the difference in median time to disease progression was only 1 month, older women had significantly shorter median OS than younger women (37 vs. 45 months, P < .001).

A number of prospective ovarian cancer trials have enrolled exclusively older women, or have analyzed their older subjects separately. Modified regimens studied or being studied in vulnerable populations include increased use of growth factor, single-agent carboplatin chemotherapy, and weekly low-dose chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy—First Line

European Studies: The French National Group of Investigators for the study of Ovarian and Breast Cancer (GINECO) has performed a series of front-line chemotherapy trials for patients aged 70 years and older with advanced ovarian cancer, and used them to develop a decision aid (Geriatric Vulnerability Score [GVS]) for identifying which patients will not tolerate aggressive chemotherapy (11,22–24). The trials used carboplatin/cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel/cyclophosphamide, and single-agent carboplatin. Rates of completion of six cycles of chemotherapy were 75.6%, 68.1%, and 74% for the three trials respectively. OS for each of the trials was 21.6 months/25.9 months/17.4 months. The GVS score is being used in the ongoing Elderly Women in Ovarian Cancer (EWOC) trial that randomizes newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients with a GVS of three or higher to treatment with single-agent carboplatin AUC 5-6, every 3 week carboplatin AUC 5-6 plus every 3 week paclitaxel 175 mg/m2, and carboplatin AUC 2 plus paclitaxel 60 mg/m2 both administered weekly for 3 weeks on an every 4 week schedule.

Weekly dosing of chemotherapy is particularly of interest. A carboplatin and paclitaxel combination was explored in the phase II Multicenter Italian Trial in Ovarian cancer (MITO-5) study, which included 26 vulnerable patients aged 70 years or older (25). The response rate was 38.5%, and median OS was 32.0 months. Toxicity was low, with 23 patients (89%) treated without experiencing serious adverse events. Though not specific to older adult women, these data were confirmed in a subsequent phase III MITO-7 study that compared carboplatin (AUC 6) with paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) every 3 weeks to a weekly carboplatin (AUC 2) and weekly paclitaxel (60 mg/m2) regimen given over 18 weeks in more than 800 women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer at any age (median 59 and 60 years, respectively) and any stage (more than 80% with stage III to IV disease) (26). Compared with the women in the every-3-week arm, there was no difference in 175progression-free survival (PFS) with weekly dosing (median, 17.3 vs. 18.3 months, HR 0.96, P = .066). However, weekly dosing was associated with better quality of life scores and lower toxicities, including grade 2 or worse neuropathy, and serious (grade 3 to 4) hematologic toxicity. These data suggest that weekly dosing of carboplatin and paclitaxel may be a more reasonable option for older patients, especially those deemed to be at higher risk for treatment-related toxicities (25).

US Studies: The administration of reduced doses of carboplatin and paclitaxel was evaluated retrospectively in a group of patients older than 70 years (27). Compared with treatment using reduced doses, standard administration of chemotherapy resulted in a significantly higher incidence of grade 3 to 4 neutropenia (54% vs. 19%). In addition, those patients treated with standard doses were more likely to experience cumulative toxicity and require treatment delays. Importantly, there were no differences in PFS or OS between cohorts.

VonGruenigen led a trial of women 70 years and older with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer receiving first-line platinum-based chemotherapy (GOG 273) (12). Patients and their physicians selected from two different regimens: (Arm 1) every 3 week carboplatin AUC 5, paclitaxel 135 mg/m2, and pegfilgrastim support; or (Arm 2) every 3 week single-agent carboplatin AUC 5. Patients could be enrolled either after CRS or prior to any surgical intervention. One hundred fifty-three women enrolled into Arm 1 and 59 into Arm 2. Women on Arm 2 were older (median age 83 vs. 77 years), had lower PS (PS2-3: 37% vs. 11%), were more likely to receive chemotherapy prior to surgery (58% vs. 49%) and less likely to complete all four cycles without dose reduction or a more than 7-day delay (54% vs. 82%). However, in general, overall completion of four cycles of chemotherapy was high (Arm 1: 92% and Arm 2: 75%). The ability to complete four cycles of chemotherapy without dose reduction or delay was significantly related to independence in ADLs, improved social activity and higher quality of life. IADL dependency was associated with reduced survival and higher toxicity from chemotherapy. With both regimens, patient-reported outcomes including quality of life, social activity, and function (ADLs) improved over time with cumulative chemotherapy cycles. This suggests an important symptomatic benefit of chemotherapy even in the oldest age groups.

After Arm 1 and 2 completed enrollment, Tew and colleagues explored the widely used dose-dense paclitaxel regimen. Patients were treated with carboplatin (AUC 5) every 3 weeks and dose-reduced weekly paclitaxel (60 mg/m2) on an every 3 week cycle; this arm was designed to test the hypothesis that the GOG GAS will predict ability to tolerate chemotherapy.

NACT is the delivery of chemotherapy prior to CRS. NACT use is gaining popularity in both the United States and Europe, particularly for older and vulnerable patients, because it is associated with less surgical toxicity. In an analysis of Medicare patients with stage II–IV ovarian cancer who survived at least 6 months from diagnosis, use of NACT had increased from 19.7% in 1991 to 31.8% in 2007, and is likely higher now (28). Randomized trial data suggest that outcomes with NACT and primary surgery are similar overall, though different subgroups may benefit from different approaches. A prospective randomized study of NACT (29) randomly assigned 632 patients with newly diagnosed stage IIIC or IV epithelial ovarian cancer to either 176primary CRS followed by six cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy or three cycles of platinum-based NACT followed by an interval CRS followed by an additional three cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy. The median age was 62 years (25–86) in the primary surgery group and 63 years (33–81) in the NACT group. Survival outcomes in the two arms were similar, with a median OS of 29 months in the primary surgery group and 30 months in those assigned to NACT. Surgical complications were higher in the primary surgery group, with postoperative death in 2.5% versus 0.7% and infection in 8.1% and 1.7% of participants respectively. Similar results were seen in a preliminary report from the MRC CHORUS trial, which involved an identical randomization and showed 12-month survival rates of 70% for primary surgery and 76% for NACT (30). Exploratory subgroup analyses of the EORTC trial did not show differences in benefit by age: 5-year survival rates of patients over the age of 69 (n = 166) were 20% with primary surgery and 18% with NACT (31). Interestingly, patients with stage IV tumors and large tumor volume appeared to do better with NACT, whereas patients with low tumor burden appeared to do better with primary surgery.

Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (IP): IP chemotherapy has shown a survival benefit in multiple randomized trials of patients with optimally cytoreduced ovarian cancer (32–34). Only a small fraction of the women enrolled in these trials were over the age of 70 years. All of the randomized trials used cisplatin, which has more nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and ototoxicity than carboplatin—side effects concerning for an older patient. Although some reports have suggested that healthy fit older patients can tolerate IP chemotherapy (35), one small report on women over age 75 treated with aggressive surgery followed by hyperthermic IP found a 78% morbidity rate (36).

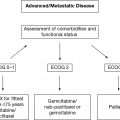

Chemotherapy for Recurrent Disease

For patients with platinum-sensitive disease (>6 months in remission since last platinum treatment), randomized trials show a PFS advantage to a doublet combination with carboplatin and either paclitaxel, gemcitabine (37), or liposomal doxorubicin (38) versus treatment with carboplatin alone; platinum-based doublet therapy is therefore standard. In one retrospective study, however, older women had less secondary surgery, more frequent single-agent chemotherapy, and lower response rates to chemotherapy (67.2% vs. 46.5%) (39). Choice of regimen is often based on the toxicity profile, and in older patients, gemcitabine can produce higher rates of cytopenias and paclitaxel higher rates of neuropathy. A subset analysis of patients aged 70 years and older treated on the CALYPSO trial (carboplatin/paclitaxel [CP] vs. carboplatin/liposomal doxorubicin [CD]) showed that elderly patients completed the planned six cycles at the same rate as younger patients (79% for CP and 82% for CD), and had similar rates of hematologic toxicity. Grade 2 or greater peripheral neuropathy was greater among older patients treated with paclitaxel (36% vs. 24% for younger patients) and, interestingly, carboplatin hypersensitivity reactions were significantly less common in older women (40).

177For platinum-resistant disease, chemotherapy is typically given as single agent and responses range from 10% to 25% with a median duration from 4 to 8 months. Common options include liposomal doxorubicin, topotecan, gemcitabine, weekly paclitaxel, and vinorelbine (41). Liposomal doxorubicin or gemcitabine are reasonable choices for older patients with platinum-resistant disease, given their relatively good toxicity profiles. However, because these chemotherapy options only offer a low chance of disease palliation, it may be reasonable to focus on better supportive measures, rather than more chemotherapy, in the setting of platinum-resistant disease. Disease progression on two consecutive lines of therapy has been recommended as a guide to stop therapy (42). In one study, there was a significant cost difference with no appreciable improvement in survival between ovarian cancer patients treated aggressively with chemotherapy versus those enrolled in hospice at the final months of their life. The authors suggest that earlier hospice enrollment is beneficial, particularly in older frail patients (43).

Targeted Agents

The targeted agents currently of most relevance to the treatment of ovarian cancer are the Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors and antiangiogenic agents. There are no elderly-specific data on PARP inhibitors, but they appear generally to be well tolerated (low-grade fatigue, GI symptoms, anemia, and rash) (44). PARP inhibitors have increased activity in women with a BRCA mutation. Although BRCA-linked hereditary ovarian cancers, particularly BRCA1-associated cancers, tend to occur at a younger age than nonhereditary/sporadic ovarian cancer, the mean age at time of ovarian cancer diagnosis for mutation carriers ranges significantly (BRCA1: 54 years [31–79], BRCA2: 62 years [44–77], and sporadic: 63 years [25–87]) (45). Genetic counseling and consideration of PARP inhibitor therapy are appropriate regardless of age.

Antiangiogenic agents require more caution in the older population. Although the effect of bevacizumab on survival outcomes appears to be similar in older and younger patients with ovarian cancer (46), a variety of toxicities are increased in the older population. Of particular concern are vascular events. The package insert for bevacizumab as of September 2014 notes that in an exploratory pooled analysis of 1,745 patients treated in five randomized controlled studies, the rate of arterial thromboembolic events in bevacizumab-treated patients was 8.5% for those aged 65 years and older versus 2.9% for those younger than 65 years of age (47). Patients with a history of prior stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) should not receive bevacizumab, and close attention must be paid to blood pressure control. Mohile et al. conducted a prospective analysis of toxicity in older patients receiving bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy for colon cancer or non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The addition of bevacizumab increased toxicity, particularly grade 3 hypertension, but no GA variables were found to be associated with increased toxicity (48). Anti-VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitors are of increasing interest in ovarian cancer, but significant side effects have been observed in older adults (fatigue, diarrhea, and hypertension) (49–53).

TAKE HOME POINTS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree