Orthopedic Syndromes

Orthopedic (bone and joint) infections can be classified into syndromes according to the anatomic area involved and the rate of onset.

Acute arthritis can be defined as a warm, swollen, erythematous joint. It is typically very painful and tender. Purulent arthritis (sometimes called pyogenic arthritis or pyarthritis) can be defined as cloudy, purulent fluid in a joint and is almost always secondary to a bacterial infection, although the culture is not always positive. The term septic arthritis implies a bacterial arthritis confirmed by culture. Synovitis can be defined as inflammation in a joint, with sterile fluid and no preceding antibiotics. Usually, the fluid is relatively clear and serous.

Osteomyelitis can be defined as infection in a bone. Diskitis (spondylitis) is an inflammatory process (with or without infection) of the intervertebral disk, often involving the adjacent vertebral bodies. Chondritis is infection of cartilage; adjacent bone may be infected as well, in which case the term osteochondritis is used.

Cellulitis (see Chapter 17) can be defined as inflammation (manifested as localized redness) of the skin and underlying soft tissue. Cellulitis over a bone or joint is often a sign of infection of the bone or joint.

Classification of Acute Arthritis

Acute Monarticular Arthritis

Acute monarticular arthritis is characterized by a rapid onset, usually with fever. The joint will typically be red, swollen, tender, and warm, with significant pain on motion of the joint. When a child has fever with a single hot and swollen joint, septic arthritis is sufficiently likely that joint aspiration should be done.

Acute Polyarticular Arthritis

Acute arthritis involving more than one joint in a child usually raises the question of acute rheumatic fever (Chapter 18) or juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (Chapter 10). However, septic arthritis can involve more than one joint, particularly with staphylococcal or gonococcal bacteremia during the newborn period or with intravenous drug use.

Subacute or Chronic Arthritis

Subacute or chronic arthritis can be defined as arthritis with gradual onset and duration of weeks to months, with little or no fever and slow progression. Tenderness, swelling, and limitation of motion may be persistent or recur episodically. The most likely infectious causes are partially treated or subacute septic arthritis. Lyme disease and tuberculosis are possibilities in the patient with an appropriate exposure history. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), aseptic necrosis, and neoplasm should be considered. Occasionally, a congenital coagulation defect will be unrecognized until bleeding into a joint occurs and aspiration reveals a hemarthrosis. A chronic or recurrent monarticular arthritis is often due to JRA and a slit-lamp examination looking for iridocyclitis is indicated. In addition, a therapeutic trial of ibuprofen or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent is often prescribed.

Acute Tenosynovitis

Acute tenosynovitis is characterized by swelling, tenderness, and pain on motion of the tendon sheaths, especially over the wrist, foot, or ankle. In the sexually active adolescent, gonococcal infection is a common cause.

Acute Arthralgia

Acute arthralgia is characterized by joint aching without objective signs on physical examination. If more than one joint is involved the term “polyarthralgia” is used. The causes of acute polyarthritis should be considered first, because objective findings might be subtle or delayed. However, fever

from any cause is often associated with polyarthralgia. Muscle aches (myalgia) are often associated with acute viral infections such as influenza and may be mistaken for polyarthralgia.

from any cause is often associated with polyarthralgia. Muscle aches (myalgia) are often associated with acute viral infections such as influenza and may be mistaken for polyarthralgia.

Acute Myalgia

Acute polymyalgia, like acute polyarthralgia, is often a nonspecific manifestation of a febrile illness. The term “acute myositis” should be reserved for cases of muscle inflammation proved by biopsy or by an increased serum concentration of muscle enzymes, such as creatinine kinase and aldolase.

Infectious Arthritis

Importance of Septic Arthritis

Septic arthritis is a medical emergency. Early diagnosis and proper treatment can usually prevent permanent disability. The most important characteristic of septic arthritis in children is that subsequent growth is likely to exaggerate any deformity caused by the illness, especially in the hip joint. Diagnostic aspiration should be done as soon as joint swelling or tenderness is recognized, and maximum therapeutic efforts should be made as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed by aspiration of pus. This is particularly true of septic arthritis of the hip, where destruction of the epiphyseal growth plate can result in unequal leg length or fusion of the joint, with severe gait disturbance. Several studies have demonstrated the importance of prompt surgical drainage. A delay of more than 4 days from onset of symptoms to decompression of the hip joint is the most important prognostic risk factor for permanent sequelae.1,2,3,4

Mechanisms

Septic arthritis in children most commonly occurs via hematogenous seeding of the synovial space. Occasionally, it occurs by local spread of contiguous infection or is secondary to trauma or surgery. The blood supply to the head of the femur and to the humerus is by way of the proximal metaphyseal (retinacular) arteries, which lie within the joint cavity.5 These vessels can be compressed by increased intra-articular pressure, with resultant ischemia and destruction of the epiphyseal growth plate. Compromised blood supply can also lead to avascular necrosis of the femur or humerus. Therefore, most orthopedic surgeons strongly urge prompt open drainage of purulent arthritis, especially when these joints are involved.

The action of proteolytic enzymes in pus, even when it is sterile, can destroy joint cartilage, with resultant joint deformity and crippling.6 Therefore, preservation of joint cartilage is another reason for thorough removal of pus from joint spaces. Often, as much as 100 mL of pus can be removed from a joint during an operation after the joint was thought to have been tapped dry by needle aspiration. This may be explained by loculation of the pus, especially if the onset has been subacute.

Presentation

The most frequent joints involved are those of the lower extremity, and thus the child will usually present with acute onset of limp or refusal to walk. The child with septic arthritis of the hip will occasionally complain only of referred knee pain. If a joint in the upper extremity is involved, the child will usually refuse to move the arm. The joint is typically held in the position of least pain (usually flexion). Most children will have fever, but occasionally it is low-grade. In one study of children less than 2 years old with septic arthritis, 14 (35%) of 40 had a temperature less than 38.3°C.7 A careful examination will reveal a red, swollen, and tender joint with pain on motion. Detecting infection in joints that are not easily isolated on examination, such as the sacroiliac and sternoclavicular joints, is difficult and requires a high index of suspicion.

Bacterial Causes of Arthritis

Pyogenic Organisms

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause of septic arthritis in all ages, although Group B streptococcus is also a common cause in newborns. Prior to the routine use the of conjugated vaccine in the early 1990s, Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) was a common cause of septic arthritis in children but has now become rare.8 Kingella kingae has become the most frequent gram-negative organism causing septic arthritis in young children.9 The common causes of bacterial arthritis and predisposing factors are shown in Table 16-1.

Acute bacterial arthritis is usually monarticular but is often polyarticular in neonates and in adolescents with gonococcal arthritis. Polyarticular pneumococcal arthritis has been described in children with HIV infection.10 Occasionally, previously

healthy children will present with multiple joint involvement in the context of severe staphylococcal sepsis, with or without meeting the criteria for toxic shock syndrome.11 In addition, acute polyarthritis can occur as a complication of a systemic bacterial infection without infection of the joint. Bacterial endocarditis is often associated with musculoskeletal manifestations, such as arthritis, arthralgia, and myalgia.12 These patterns are probably best classified with the reactive arthritides.

healthy children will present with multiple joint involvement in the context of severe staphylococcal sepsis, with or without meeting the criteria for toxic shock syndrome.11 In addition, acute polyarthritis can occur as a complication of a systemic bacterial infection without infection of the joint. Bacterial endocarditis is often associated with musculoskeletal manifestations, such as arthritis, arthralgia, and myalgia.12 These patterns are probably best classified with the reactive arthritides.

TABLE 16-1. PREDISPOSING FACTORS AND CAUSES OF BACTERIAL ARTHRITIS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Recurrent bacterial arthritis is uncommon and should suggest underlying immunodeficiency, such as agammaglobulinemia.13 In one series of patients with hypogammaglobulinemia, 8 (38%) of 21 episodes of septic arthritis were attributed to Mycoplasma or Ureaplasma.14 Patients with chronic lymphedema are also predisposed to recurrent arthritis in the involved limb.15 Septic arthritis due to Salmonella occurs with greater frequency in patients with sickle cell anemia as well as those with systemic lupus erythematosus.16,17

Lyme Arthritis

In a child who lives in or has visited an endemic area (primarily the northeastern and mid-Atlantic

states and parts of Wisconsin and Minnesota), Lyme disease is a possible cause of arthritis. Characteristically, one or two large joints suddenly become swollen and warm, but there is often minimal pain or erythema.18 The knee is the most frequently affected joint. There may or may not be a history of a tick bite or an erythema migrans rash. However, by the time arthritis develops (usually several weeks after infection), a specific IgG and IgM antibody response in the serum to Borrelia burgdorferi is nearly always present.19 Synovial fluid leukocyte counts are typically less than 50,000 per mcL but range from 500–100,000 per mcL, usually with a neutrophil predominance.20 Using PCR, B. burgdorferi DNA can be detected in the synovial fluid of patients with Lyme arthritis.21 In the small percentage of patients who develop chronic arthritis despite antimicrobial therapy, PCR testing is negative.21 Thus, in addition to causing infectious arthritis, B. burgdorferi can apparently cause a form of reactive arthritis in some genetically-predisposed people.22 Chronic arthritis in children with Lyme disease is uncommon; greater than 95% of children treated with an appropriate course of antibiotics have no long-term symptoms.23

states and parts of Wisconsin and Minnesota), Lyme disease is a possible cause of arthritis. Characteristically, one or two large joints suddenly become swollen and warm, but there is often minimal pain or erythema.18 The knee is the most frequently affected joint. There may or may not be a history of a tick bite or an erythema migrans rash. However, by the time arthritis develops (usually several weeks after infection), a specific IgG and IgM antibody response in the serum to Borrelia burgdorferi is nearly always present.19 Synovial fluid leukocyte counts are typically less than 50,000 per mcL but range from 500–100,000 per mcL, usually with a neutrophil predominance.20 Using PCR, B. burgdorferi DNA can be detected in the synovial fluid of patients with Lyme arthritis.21 In the small percentage of patients who develop chronic arthritis despite antimicrobial therapy, PCR testing is negative.21 Thus, in addition to causing infectious arthritis, B. burgdorferi can apparently cause a form of reactive arthritis in some genetically-predisposed people.22 Chronic arthritis in children with Lyme disease is uncommon; greater than 95% of children treated with an appropriate course of antibiotics have no long-term symptoms.23

It is not uncommon for a parent to request testing for Lyme disease in a child with nonspecific symptoms, such as headache, fatigue, and arthralgia. In the absence of a history of erythema migrans or objective findings (such as arthritis, carditis, meningitis, or neuritis), the likelihood of Lyme disease is remote. In such children the positive predictive value of serologic testing is less than 5%; that is, nearly all positive tests are false-positives.24 For persons not residing in a Lyme-endemic region, the positive predictive value of serologic tests approaches zero. Testing for Lyme disease in such patients is counterproductive, because a positive test is likely to result in delayed treatment of the correct diagnosis, such as fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome.25

Septic Arthritis in the Neonate and Young Infant

The young infant with septic arthritis may present acutely with lethargy, fever or hypothermia, and poor feeding. However, the presentation is often subtle and subacute, without systemic symptoms.26 Redness and warmth may be absent and swelling may be difficult to appreciate, especially in the hip. Irritability during diaper changes, lack of movement of an extremity (which may be misdiagnosed as an isolated nerve palsy), or even limb cyanosis may be the only clue to the diagnosis.27,28 Decreased extremity movement is usually secondary to pain (so-called “pseudoparalysis”) but is occasionally the result of true paralysis from nerve impingement, especially when the shoulder is involved.29 In the case of hip joint infection, the child will prefer to hold the extremity in external rotation, abduction, and flexion to reduce intra-articular pressure. Polyarticular infection and concomitant osteomyelitis are common (as discussed in the section on osteomyelitis).30 Risk factors include prematurity, indwelling intravascular catheters (especially umbilical arterial lines), and femoral venipuncture.26,31

Postoperative Septic Arthritis

In comparison with adults, a history of previous joint surgery in children is very uncommon. However, prosthetic joints are occasionally placed in children or adolescents after limb salvage, resection of bone tumors, after major trauma, or in children with severe disability from rheumatoid arthritis or other conditions.32,33 Infection in such joints may be subtle; fever and joint swelling occur in a minority of cases.34 Joint pain, which is nearly always present, may be the only symptom.34 Constant pain is suggestive of infection, whereas mechanical loosening commonly causes pain only with motion and weight bearing. Nearly any organism, including those normally considered contaminants, can cause prosthetic joint infection. In one study over a 23-year period, prosthetic joint infection occurred in 466 (1.8%) of 26,505 recipients.35 The most common etiologic agents were S. aureus (22%), coagulase-negative staphylococci (19%), streptococci (9%), gram-negative bacilli (8%), anaerobes (6%), and other agents (5%). In addition, 19% of infections were polymicrobial. Independent risk factors for infection included malignancy, postoperative surgical site infection, and a history of previous joint arthroplasty. Removal of the prosthesis is usually required for successful treatment. For some bone cancer patients this would necessitate limb amputation, and thus lifelong antibiotic therapy may be used instead in an attempt to chronically suppress infection.

Septic arthritis after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is even less common, occurring in 7 (0.3%) of 2500 patients in one

study.36 As in the case with prosthetic joint infections, the allograft must usually be removed to effect a cure.

study.36 As in the case with prosthetic joint infections, the allograft must usually be removed to effect a cure.

Mycobacterial and Fungal Arthritis

Bone or joint involvement occurs in about 5% of cases of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis in children.37 Presentation may mimic bacterial arthritis38 or JRA.39 For any child with arthritis, risk factors for exposure to tuberculosis should be elicited (see Chapter 8) and, if present, a chest x-ray and tuberculin skin test should be performed. Keep in mind, however, that these tests are often negative in the child with extrapulmonary tuberculosis.40 Joint fluid will typically have fewer than 50,000 leukocytes per mcL with a neutrophilic predominance, but these findings are variable. When suspected, a smear for acid-fast bacilli and mycobacterial culture should be performed on the joint fluid. Occasionally, synovial biopsy is required to make the diagnosis.40 Joint involvement with nontuberculous mycobacteria is most commonly reported in the setting of HIV infection41 but has been described in an immunocompetent child.42

Candidal arthritis is uncommon, with the notable exception being premature neonates. In one study, Candida species were responsible for 17% of episodes of hospital-acquired neonatal septic arthritis, second in frequency only to staphylococci.43 Besides prematurity, other risk factors often present in these infants include central venous catheters, prolonged use of antibiotics, hyperalimentation, and recent surgery.44,45 Septic arthritis is an uncommon manifestation of disseminated candidiasis in patients with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia.46

TABLE 16-2. VIRAL CAUSES OF ARTHRITIS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Other fungal infections rarely causing arthritis include histoplasmosis,47 blastomycosis,48 cryptococcosis,49 coccidioidomycosis,50 sporotrichosis,51 and aspergillosis,52 most commonly—but not exclusively—in immunocompromised hosts. Patients with histoplasmosis can also develop a reactive arthritis, sometimes in association with other inflammatory phenomena, such as erythema nodosum.53

Viral Arthritis

Several viruses have been associated with arthritis (Table 16-2). In many cases, such as with parvovirus B19,54 the process resembles a reactive arthritis rather than viral infection of the synovial space. Patients with HIV infection have a higher incidence of several types of arthritis, including septic arthritis and Reiter syndrome.55 In addition, there appears to be an entity of HIV-associated arthritis, which occurs in up to 8% of infected patients.56 Like other viral arthritides, it is typically an acute-onset oligoarticular arthritis of relatively brief duration and does not cause permanent joint damage. Both natural

rubella infection and, much less commonly, vaccination with live-attenuated rubella vaccine are associated with inflammation of the small joints.57 As with parvovirus B19-associated arthritis, young adult women are more likely to develop rubella-associated arthritis.

rubella infection and, much less commonly, vaccination with live-attenuated rubella vaccine are associated with inflammation of the small joints.57 As with parvovirus B19-associated arthritis, young adult women are more likely to develop rubella-associated arthritis.

Differential Diagnosis of Infectious Arthritis

Many diseases resemble septic arthritis. Some of the more common of these can be brought to mind by recalling the acrostic JOINT STARTS HOT (Table 16-3).

Osteomyelitis

The most important consideration in suspected septic arthritis of the hip is osteomyelitis of the femoral neck or, less commonly, of a pelvic bone (see the section on osteomyelitis). It is also important to remember that osteomyelitis and septic arthritis sometimes occur together.30

TABLE 16-3. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF SEPTIC ARTHRITIS: JOINT STARTS HOT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Joint Effusion Near Osteomyelitis

Sometimes called a “sympathetic effusion,” joint fluid near an osteomyelitis closely resembles septic arthritis clinically. However, aspiration of the joint reveals relatively clear fluid, without bacteria present on the Gram stain. Only joint aspiration can distinguish between a purulent and a sympathetic effusion in a joint adjacent to an area of osteomyelitis, although range of motion is usually less limited in a sympathetic effusion. The pus formed in the metaphysis in osteomyelitis may break through into the joint space, especially in joints where the metaphyseal spongiosa lies within the attachments of the joint capsule, as in the hip and shoulder.58 To avoid the damaging effects of pressure and pus, it is essential to aspirate such joints to recognize a purulent arthritis. When the joint tap is nonpurulent in suspected septic arthritis of the hip, a bone scan should be done to look for femoral neck osteomyelitis.

Transient Synovitis of the Hip

Transient synovitis, also called “toxic synovitis” or “irritable hip,” is manifested by unilateral hip pain,

refusal to walk, or limping, and is a frequent cause of arthritis in children. In fact, it is the most common cause of atraumatic limp in children presenting to the emergency department, accounting for about 40% of such visits in one study.59 Fever, if present, is usually low-grade. Transient synovitis is much more frequent than septic arthritis of the hip. Nevertheless, the physician must not assume that a child with a swollen, painful hip joint has transient synovitis rather than septic arthritis. The risks of diagnostic joint aspiration performed by a physician who is experienced in this procedure are small compared with the dangers of a destructive septic arthritis. Ultrasound is not helpful in distinguishing transient synovitis from septic arthritis because an effusion is found in both conditions.

refusal to walk, or limping, and is a frequent cause of arthritis in children. In fact, it is the most common cause of atraumatic limp in children presenting to the emergency department, accounting for about 40% of such visits in one study.59 Fever, if present, is usually low-grade. Transient synovitis is much more frequent than septic arthritis of the hip. Nevertheless, the physician must not assume that a child with a swollen, painful hip joint has transient synovitis rather than septic arthritis. The risks of diagnostic joint aspiration performed by a physician who is experienced in this procedure are small compared with the dangers of a destructive septic arthritis. Ultrasound is not helpful in distinguishing transient synovitis from septic arthritis because an effusion is found in both conditions.

Several algorithms have been developed to assist in determining the likelihood of septic arthritis vs. transient synovitis. Kocher et al.60 reviewed the charts of all children presenting to Children’s Hospital in Boston with an irritable hip over an 18-year period. Of 262 children, 82 were diagnosed with confirmed or presumed septic arthritis, 86 were diagnosed with transient synovitis, and 114 were excluded. Lack of synovial fluid studies was the most common reason for exclusion, and, presumably, many of these children had transient synovitis. In multivariate analysis, four variables were found to be independent predictors of septic arthritis: a history of subjective fever, non-weight-bearing, ESR 40 mm/hour or greater, and peripheral WBC greater than 12,000 per mcL. The probability of septic arthritis could be calculated based on the number of these variables present (Table 16-4). Using this algorithm, children with three or four predictors should usually undergo hip aspiration in the operating room, given the high likelihood that arthrotomy and drainage will be needed. Children with two predictors may be good candidates for aspiration in the outpatient setting. Depending on clinical suspicion, some children with fewer than two predictors will be appropriate candidates for careful observation without aspiration. Other similar algorithms have been developed.61,62 It is important to remember that the utility of such algorithms may be lower in children less than 18–24 months of age, in whom transient synovitis is less common and in whom the presentation of septic arthritis is often subtle.

TABLE 16-4. PREDICTED PROBABILITY OF SEPTIC ARTHRITIS VS. TRANSIENT SYNOVITIS BASED ON THE PRESENCE OF FOUR VARIABLS60 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The cause of transient synovitis of the hip is unknown. Symptoms usually last only a few days, although it can be recurrent. Legg-Calve-Perthes disease (aseptic necrosis of the femoral capital epiphysis) in its early stage may cause synovitis that is indistinguishable from transient synovitis, so that patients with synovitis should have careful evaluation and follow-up, with referral to an orthopedic surgeon if symptoms persist.

Cellulitis

Cellulitis near a joint may resemble acute arthritis. However, with septic arthritis the erythema is usually symmetrically distributed around the joint, and the borders of redness are diffuse. Motion of the joint is usually exquisitely painful. Cellulitis will typically have more well-demarcated erythema, often with evidence of a local wound, and joint motion causes little discomfort. Despite these generalizations, it is often difficult to tell whether the

joint is involved. Diagnostic aspiration (avoiding the cellulitis, if possible) should usually be done if there is reasonable suspicion of increased fluid in the joint. The risk of introducing bacteria from cellulitis into the joint is small compared with the risk of delay in diagnosing septic arthritis. In certain cases, ultrasound may be performed first and, if there is no joint effusion, arthrocentesis can be avoided. However, the ultrasound must be done in a timely fashion by a radiologist expert in interpreting the results. Sonography is useful for excluding joint effusion in the hip but may be less sensitive in detecting fluid in smaller joints. If no joint fluid is present by clinical or ultrasound examination (and osteomyelitis is not suspected or has been ruled out), blood cultures should be obtained and the patient should be treated with intravenous antibiotics such as oxacillin or cefazolin to cover S. aureus and Group A streptococcus. The patient usually responds promptly when cellulitis without underlying septic arthritis is present, as discussed in Chapter 17.

joint is involved. Diagnostic aspiration (avoiding the cellulitis, if possible) should usually be done if there is reasonable suspicion of increased fluid in the joint. The risk of introducing bacteria from cellulitis into the joint is small compared with the risk of delay in diagnosing septic arthritis. In certain cases, ultrasound may be performed first and, if there is no joint effusion, arthrocentesis can be avoided. However, the ultrasound must be done in a timely fashion by a radiologist expert in interpreting the results. Sonography is useful for excluding joint effusion in the hip but may be less sensitive in detecting fluid in smaller joints. If no joint fluid is present by clinical or ultrasound examination (and osteomyelitis is not suspected or has been ruled out), blood cultures should be obtained and the patient should be treated with intravenous antibiotics such as oxacillin or cefazolin to cover S. aureus and Group A streptococcus. The patient usually responds promptly when cellulitis without underlying septic arthritis is present, as discussed in Chapter 17.

Septic Bursitis

Bacterial infection of a bursa is usually secondary to a local laceration or abrasion of the skin.63 In children, this condition is most frequently observed in the prepatellar bursa after an abrasion of the knee. Septic prepatellar bursitis can usually be distinguished from septic arthritis of the knee by physical examination, because there is less pain on motion in bursitis. Treatment with drainage and antibiotics is similar to that for a skin abscess.

Reactive Arthritis

Reactive arthritis is defined as a nonpurulent arthritis that occurs simultaneously or subsequent to an infection elsewhere in the body. The larger joints are more commonly affected. Onset is typically acute and fever may be present. The most well recognized associations are with various causes of bacterial enteritis and genital infection (see Box 16-1). There remains considerable debate as to whether such arthritis is caused by occult infection in the joint or by an immune response to infection.64 It is possible that different mechanisms are operative depending on the pathogen responsible. Nucleic acid of Chlamydia trachomatis and, less frequently, C. pneumoniae has been found in the synovial tissue of patients with reactive arthritis.65,66 Chlamydia DNA is present in the synovial tissue of a small percentage of asymptomatic subjects as well.67

BOX 16-1 Some Causes of Post-Infectious Reactive Arthritis

| Diarrheal Salmonella*†264 Campylobacter*265 Yersinia*266 Shigella267,268 Clostridium difficile269,270 Giardia271 |

| Meningeal Neisseria meningitidis†272 Haemophilus influenzae type b†273 |

| Genital Chiamydia trachomatis*274 Neisseria gonorrheae†275 Ureaplasma urealyticum276 Mycoplasma hominis277 |

| Other Chlamydia pneumoniae278 Group A streptococci†279 Group C and G streptococci280 Mycoplasma pneumoniae277 Hepatitis A, B, and C281,282,283 Propionibacterium acnes284 |

| * more common cause of reactive arthritis † also causes purulent arthritis |

Some patients are genetically predisposed—there is a higher incidence of the HLA-B27 phenotype in patients with reactive arthritis—but this does not explain all cases. Some infectious agents, such as meningococcus68 and Group A streptococcus,69,70 can cause either purulent arthritis or reactive arthritis. The mechanism of arthritis for many viral infections may be immune-related, and these can be considered a form of reactive arthritis. Several vaccines have been anecdotally associated with the development of reactive arthritis.71,72,73,74,75,76,77 “Reiter’s syndrome” is the term used for the subset of patients with reactive arthritis who also have nongonococcal urethritis and ocular inflammation.78

Arthritis Associated with Systemic Disease

Many systemic inflammatory diseases may have arthritis as part of the clinical presentation. These include collagen vascular diseases such as JRA,79 systemic

lupus erythematosis,80 mixed connective tissue disease,81 juvenile ankylosing spondylitis,81a and polymyositis and dermatomyositis.82 Other systemic diseases that may present with arthritis include acute rheumatic fever,83 inflammatory bowel disease,84 Kawasaki disease,85 sarcoidosis,85a and Henoch-Schöenlein purpura.86 Serum sickness is also a consideration, particularly in the child who has received medication in the previous 2 weeks.87 Approximately 5–10% of children with cystic fibrosis have episodic arthritis that is probably immune-mediated.88

lupus erythematosis,80 mixed connective tissue disease,81 juvenile ankylosing spondylitis,81a and polymyositis and dermatomyositis.82 Other systemic diseases that may present with arthritis include acute rheumatic fever,83 inflammatory bowel disease,84 Kawasaki disease,85 sarcoidosis,85a and Henoch-Schöenlein purpura.86 Serum sickness is also a consideration, particularly in the child who has received medication in the previous 2 weeks.87 Approximately 5–10% of children with cystic fibrosis have episodic arthritis that is probably immune-mediated.88

Arthritis Associated with Malignancies

Several malignant conditions in childhood may initially manifest joint involvement, especially leukemia and neuroblastoma.89 Laboratory clues to the presence of malignancy include anemia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) in the presence of a normal or decreased platelet count, and elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).90

Trauma

Trauma with bleeding into the joint may mimic septic arthritis. A history of only mild trauma resulting in significant joint swelling should raise suspicion for child abuse or an underlying coagulation disorder. It should also be kept in mind that a history of recent trauma to the joint is very common in children with septic arthritis, and such a history should not decrease suspicion for this diagnosis.

Penetrating foreign body injury to the joint may result in a presentation identical to septic arthritis.91,92 Cultures are usually sterile, but such injury can occasionally inoculate bacteria into the joint resulting in a traumatic septic arthritis.93,94 Clenched fist human bite injuries commonly cause infection of the underlying metacarpal-phalangeal joint.95 Early surgical exploration is indicated for such injuries, and prophylaxis with amoxicillin-clavulanate is appropriate to cover the commonly implicated organisms (streptococci, S. aureus, Eikenella corrodens, and anaerobes).

Diagnostic Approach

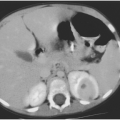

Ordinary Roentgenograms

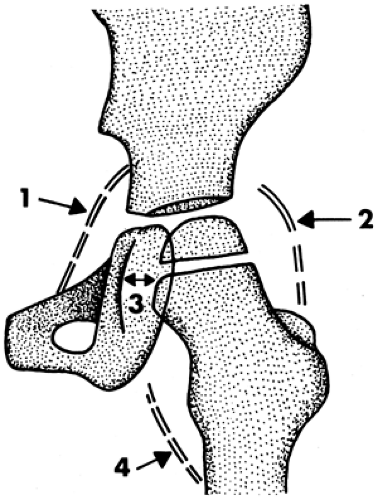

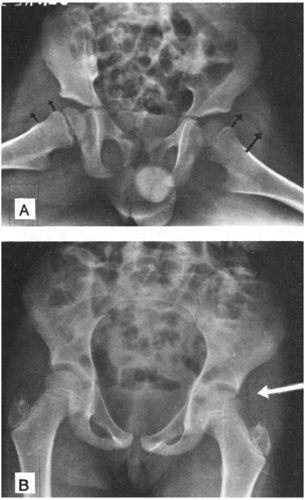

Radiologic examination may be useful to indicate the presence of fluid in the hip joint, which is difficult to detect by physical examination (Figs. 16-1 and 16-2), although ultrasound is superior for this purpose. Plain film x-rays are most helpful to detect an unsuspected fracture or chronic bone or joint disease, and thus their use is justified. However, they are not helpful in excluding the diagnosis of septic arthritis.

Ultrasound

Radionuclide Scan

Scanning with radioactive technetium (99mTc) is especially useful to detect septic arthritis in joints that are difficult to examine clinically, such as the sacroiliac area.98 On bone scan, septic arthritis usually

reveals diffuse, faintly increased tracer uptake on both sides of the joint. In osteomyelitis, the increased tracer uptake is usually unilateral and more intense, but differentiating the two conditions may be difficult.99 In some cases of septic arthritis of the hip, fluid in the joint under pressure causes impaired perfusion and decreased tracer uptake (“cold-hip” sign).100

reveals diffuse, faintly increased tracer uptake on both sides of the joint. In osteomyelitis, the increased tracer uptake is usually unilateral and more intense, but differentiating the two conditions may be difficult.99 In some cases of septic arthritis of the hip, fluid in the joint under pressure causes impaired perfusion and decreased tracer uptake (“cold-hip” sign).100

Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

These studies are of limited usefulness, because joint fluid and synovial enhancement will be seen on CT or MRI with arthritis of any cause.99 Their main utility in this setting is in looking for an associated osteomyelitis.

Arthrocentesis

If a joint effusion is suspected because of clinical or imaging findings, an arthrocentesis should be done. Some of the fluid should be put in a tube containing an anticoagulant for use in studies that cannot be done with clotted blood. Such clotting is due to fibrin, which is not present in normal joints. A white cell count and differential should be done, and the joint fluid should be Gram stained, noting the frequency of leukocytes as well as looking for bacteria. Bacterial antigen detection tests are neither approved for use with joint fluid nor helpful in diagnosing or excluding septic arthritis.101

The highest yield for bacterial culture is obtained by inoculating several milliliters of joint fluid directly into a standard blood culture bottle for use in an automated detection system.102 A small amount of fluid can also be inoculated into a lysis-centrifugation tube, but these tubes are not as commonly available, and whether their use increases the yield over that of the standard blood culture bottle is unclear.103 Either of these methods is superior to directly plating synovial fluid onto solid media, especially for recovery of fastidious organisms such as Kingella kingae.104 The microbiology laboratory should be notified if an unusual organism is suspected because of the patient’s exposure history. Stain and culture for fungi and mycobacteria are not necessary for most cases with an acute presentation. These tests should be considered in the immunocompromised host, the patient with a subacute or chronic course, or if an initial joint tap was culture negative and the response to empiric antibacterial therapy has been slow. Keep in mind, however, that the most common reason for a poor response to therapy is inadequate surgical drainage. Examination for crystals, an important part of synovial fluid analysis in adults, is rarely necessary in children.

Interpretation of Synovial Fluid

A presumptive diagnosis of septic arthritis can be made by immediate examination of the joint fluid, which is usually cloudy. Bacteria and a predominance of segmented neutrophils are often seen on the Gram stain. Leukocyte counts greater than 50,000 per mcL are strongly suggestive of bacterial infection, although some patients will have lower counts. Occasionally, patients with other causes of arthritis will have leukocyte counts greater than 50,000 per mcL.105 Decreased glucose and increased

protein concentrations in the joint fluid are supportive but not universal findings and should not be relied upon. Only about 30–60% of synovial fluid cultures will be positive, even in the child who has not received recent antibiotics.4,106,107,108 Thus, a negative culture does not rule out the possibility of bacterial arthritis.

protein concentrations in the joint fluid are supportive but not universal findings and should not be relied upon. Only about 30–60% of synovial fluid cultures will be positive, even in the child who has not received recent antibiotics.4,106,107,108 Thus, a negative culture does not rule out the possibility of bacterial arthritis.

Other Studies

Positive blood cultures are found in approximately 40% of children with septic arthritis.108 Thus, at least one and, preferably, two blood cultures should be obtained. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are both useful for following response to therapy and should be obtained at baseline.109 A complete blood count and peripheral smear should also be obtained, remembering that anemia, extreme leukocytosis or leukopenia, and decreased platelet count in a patient with an elevated ESR are clues to possible malignancy. If Lyme disease is suspected, a two-step approach to serologic testing is used. An enzyme immunoassay or indirect immunofluorescent assay is done first. If these screening tests are positive, they require confirmation with a Western blot assay. At least five bands must be present on the Western blot for the test to be considered positive. Caution is indicated, as we have seen children with culture-positive S. aureus septic arthritis who also had positive Western blot testing for Lyme disease. This could be secondary to an unrecognized infection with B. burgdorferi in the past, current coinfection, or a false-positive test.

Treatment

Surgical Drainage

Drainage of pus from a joint may be done by intermittent aspiration, by open incision with drainage (followed by continuous suction drainage) or by arthroscopy. The risk of severe deformity from septic arthritis in children leads most orthopedic surgeons to argue for open decompression and removal of pus. However, repeated aspiration may be acceptable for the knee, elbow, or ankle, if there is rapid improvement. In the hip and shoulder, open incision and drainage is advisable.

Antibiotic Therapy

If the joint fluid shows more than 10,000 leukocytes per mcL with a predominance of neutrophils, the working diagnosis should be “purulent arthritis, probably septic.” Antibiotic therapy should not be delayed until culture results are available. Rather, immediate intravenous therapy should be given based on the Gram stain. If the Gram stain is negative, then antibiotic therapy should be based on the most frequent organisms recovered. In most settings, empiric therapy using an agent with good activity against S. aureus, such as oxacillin or cefazolin, is appropriate. Vancomycin may be used in areas with a high prevalence of community-acquired MRSA. Clindamycin is also an option, depending on local susceptibility profiles.109a If S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, Salmonella, or N. gonorrheae are suspected, ceftriaxone or cefotaxime is added. For the neonate, oxacillin plus cefotaxime or gentamicin may be used to cover the most likely pathogens (S. aureus, Group B streptococcus, and enteric gram-negative rods). For all patients, as soon as definite culture and sensitivity results are obtained, the initial therapy can be changed, if necessary. If the isolate (usually S. aureus) is shown to be sensitive to a β-lactam antibiotic, this should be used preferentially because of greater inherent antistaphylococcal activity than vancomycin.

Rarely, slow response to therapy with a β-lactam antibiotic is the result of bacterial tolerance, rendering the antibiotic bacteriostatic instead of bactericidal.110 More commonly, poor response is secondary to inadequate drainage. Culture-negative septic arthritis is common and should be treated as aggressively as culture-positive cases,107 with therapy that ensures good coverage against S. aureus (the most frequent and serious cause).

Intra-articular antibiotics have not been shown to improve outcome.111 In addition, their use may exacerbate the inflammatory response of the synovium. A recent prospective, randomized study of septic arthritis in children reported improved outcome among patients receiving a 4-day course of intravenous dexamethasone compared with placebo controls.111a However, the incidence of residual joint dysfunction was higher in the control group than is generally seen. These findings require replication in larger studies before the use of carticosteroids in the treatment of septic arthritis becomes routine.

Lyme arthritis is treated effectively with a 4-week course of doxycycline for children older than 8 years and with amoxicillin for those 8 years old or younger.24 For the few patients with persistent arthritis despite appropriate therapy, a single

14–21-day course with ceftriaxone is sometimes used, although this approach has been shown to be of no benefit in controlled trials.112 Prolonged use of intravenous antibiotics in patients with a history of possible Lyme disease and persistent nonspecific symptoms is inappropriate. This practice has been associated with severe complications from the use of central catheters, including death.113

14–21-day course with ceftriaxone is sometimes used, although this approach has been shown to be of no benefit in controlled trials.112 Prolonged use of intravenous antibiotics in patients with a history of possible Lyme disease and persistent nonspecific symptoms is inappropriate. This practice has been associated with severe complications from the use of central catheters, including death.113

Route of Therapy

Initial therapy should be by the intravenous route. It has become common practice to switch to high-dose oral therapy after about a week in the child who has an excellent initial response to therapy, with normalization of temperature and decreased pain and swelling of the joint. Other criteria sometimes used include (1) decreasing ESR or CRP, (2) assurance of compliance, (3) identification of the organism, and (4) documentation of adequate serum levels of antibiotics. Serum bactericidal levels have also been advocated. In this test, the infecting organism must be recovered from the blood or joint fluid. The patient’s serum is obtained at the expected peak or trough concentration of the oral antibiotic and serially diluted. If the organism is killed at a 1:8 dilution at peak or 1:2 dilution at trough, the oral antibiotic is likely to be effective.114 For most antibiotics with time-dependent killing (such as the β-lactam antibiotics), trough titers are expected to be more predictive of therapeutic efficacy, and this was found to be true in a study of adults.115 In practice, serum bactericidal testing is technically difficult, and very few microbiology laboratories offer this service.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree