Occult Primary Cancer with Axillary Metastases

Alain Fourquet

Youlia M. Kirova

Breast cancer can sometimes present as an isolated axillary adenopathy without any detectable breast tumor by palpation or radiologic examination. These occult primary cancers are staged as T0, N1 (stage II in the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer/American Joint Committee classification). This staging requires that proper clinical and mammographic investigations be done to rule out the presence of a small breast tumor. If this is accomplished, axillary metastases of occult breast primary cancer represent a rare clinical entity first described by Halsted in 1907 (1).

FREQUENCY

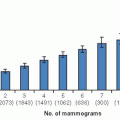

The incidence of an occult primary tumor with axillary metastases is low. Incidence rates ranged from 0.10% to 1.0% of operable breast cancers in the largest reported series (2, 3). Less than 1,500 cases have been reported in the literature since the 1950s. Because these series are limited and management policies have varied widely during this period, comparing characteristics of the patients, management, and results of treatment is difficult. Many of these patients had suspicious mammograms (4, 5 and 6). Presumably, the constant improvement of the quality of mammography and ultrasonography as well as the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has decreased the rate of occult primary tumor with axillary metastases. Interpretation of these comparisons should only be done with caution.

The characteristics of the patients with T0, N1 breast cancer are similar to those of patients with typical stage II disease. The series from the Institut Curie included 59 patients treated between 1960 and 1997. The median patient age was 57 years (range, 36 to 79 years). Thirty-four patients (58%) were postmenopausal, including two patients under hormone replacement therapy. Fifteen patients (25%) had family histories of breast cancer. Twenty-eight (47.5%) had left axillary nodes, and 31 (52.5%) had right axillary nodes.

DIAGNOSIS

Axillary Adenopathy

Isolated axillary adenopathy is a benign condition in most patients. Lymphomas are the most frequently occurring malignant tumors. Adenocarcinoma in areas other than the breast may include thyroid, lung, gastric, pancreatic, and colorectal cancer (7). These tumors, however, rarely have isolated axillary metastases as the only presentation of disease. Although in the past an extensive search for primary adenocarcinoma other than breast cancer was not recommended (6, 8, 9), these patients, nowadays, usually have computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest and abdomen for evaluation of metastases. In addition, tumor markers may help in the diagnosis of metastatic colon or pancreatic cancers.

Axillary adenopathy usually consists of one or two involved nodes, sometimes with large diameters. The median axillary node size at presentation in the patients treated at the Institut Curie was 30 mm (range, 10 to 70 mm). The initial diagnosis of malignancy was achieved by node excision in 25 of 59 patients, by fine-needle aspiration in 26 patients, and by core-needle biopsy (drill biopsy) in 8 patients.

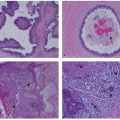

A primary breast cancer located in the axillary tail of the breast may be confounded with an axillary node. The presence of normal lymph node structure surrounding the foci of the carcinoma on the pathologic sample usually leads to the diagnosis of metastasis to a lymph node. The recognition of a metastatic lymph node can, however, be difficult because of massive involvement, with extension of the tumor into the axillary fat and disappearance of the lymphoid patterns.

Breast Cancer

Bilateral mammography should always be performed in the presence of metastatic adenocarcinoma in an axillary lymph node. Baron et al. (4) report an overall 44% accuracy in the diagnosis of occult breast cancer in a series of 34 patients, in which only nine mammographies were considered suspicious. Many of these tumors are missed owing to their relative small size and the fact that they are obscured on the mammogram by dense fibroglandular tissue (10). Nonetheless, any suspicious image should be removed for pathologic analysis.

Mammography and ultrasound have been the primary modalities for the diagnosis and the workup of breast cancer (10). Promising results were published of the use of MRI in characterizing nonpalpable, but radiologically detectable, breast lesions in patients (11, 12). In patients with T0,

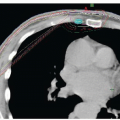

N1 breast cancer, studies have shown that MRI could detect early contrast-enhanced images in the breast. A systematic review of 7 published studies estimated that breast MRI had a 90% sensitivity and a 31% specificity in detecting the primary cancer in the breast (13). The high sensitivity of breast MRI suggests that it could be used systematically in searching for a breast primary tumor. The results of several studies of MRI in patients with occult breast cancer are shown in Table 66-1. However, because of its low specificity and the difficulties in localizing small, early contrast-enhancing foci in some instances, difficult management problems may occur. The use of MRI-directed sonographic, mammographic, or scanographic guidance (17) can help to localize the breast tumor in most patients. MRI-guided localization and biopsy can be performed (22). At the Institut Curie, 15 patients with metastatic axillary nodes, negative breast clinical examination, and without any mammographic target had breast MRI between 1997 and 2000. Early contrast-enhanced images were detected in 14 of the 15 patients (93%). A surgical excision was performed in 11 patients: in 4 patients, a second MRI-guided ultrasound examination was able to disclose and localize the breast lesion; in 3 patients localization was achieved with an orthogonal mammogram, because of the superficial localization of the lesion and the small size of the breast; and finally in 4 patients the lesion was localized using CT-scan with bolus injection. Invasive breast cancer was found in 9 of the 11 patients (82%) who underwent surgery. There is limited published experience with the use of 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in the specific setting of occult breast cancer with axillary adenopathy (23, 24). However, though it has a high specificity when detecting breast lesions, its sensitivity is low, particularly in small tumors (25). Other new breast imaging procedures are under investigation in breast cancer diagnosis (reviewed in 26): they include ionizing techniques such as scintigraphy with specific radiotracers (MIBI), non ionizing radiation imaging techniques such as color Doppler sonography (27), and optical imaging and optical imaging with fluorescent dyes coupled to probes (28). No experience has been so far reported on the use of these new techniques in the diagnosis of occult breast carcinoma.

N1 breast cancer, studies have shown that MRI could detect early contrast-enhanced images in the breast. A systematic review of 7 published studies estimated that breast MRI had a 90% sensitivity and a 31% specificity in detecting the primary cancer in the breast (13). The high sensitivity of breast MRI suggests that it could be used systematically in searching for a breast primary tumor. The results of several studies of MRI in patients with occult breast cancer are shown in Table 66-1. However, because of its low specificity and the difficulties in localizing small, early contrast-enhancing foci in some instances, difficult management problems may occur. The use of MRI-directed sonographic, mammographic, or scanographic guidance (17) can help to localize the breast tumor in most patients. MRI-guided localization and biopsy can be performed (22). At the Institut Curie, 15 patients with metastatic axillary nodes, negative breast clinical examination, and without any mammographic target had breast MRI between 1997 and 2000. Early contrast-enhanced images were detected in 14 of the 15 patients (93%). A surgical excision was performed in 11 patients: in 4 patients, a second MRI-guided ultrasound examination was able to disclose and localize the breast lesion; in 3 patients localization was achieved with an orthogonal mammogram, because of the superficial localization of the lesion and the small size of the breast; and finally in 4 patients the lesion was localized using CT-scan with bolus injection. Invasive breast cancer was found in 9 of the 11 patients (82%) who underwent surgery. There is limited published experience with the use of 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in the specific setting of occult breast cancer with axillary adenopathy (23, 24). However, though it has a high specificity when detecting breast lesions, its sensitivity is low, particularly in small tumors (25). Other new breast imaging procedures are under investigation in breast cancer diagnosis (reviewed in 26): they include ionizing techniques such as scintigraphy with specific radiotracers (MIBI), non ionizing radiation imaging techniques such as color Doppler sonography (27), and optical imaging and optical imaging with fluorescent dyes coupled to probes (28). No experience has been so far reported on the use of these new techniques in the diagnosis of occult breast carcinoma.

TABLE 66-1 Detection of Occult Breast Cancer with MRI | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In patients who have nonpalpable breast masses and normal imaging workup, the mammary origin of a metastatic adenocarcinoma to an axillary lymph node cannot be established with certainty. Therefore, the diagnosis of occult breast cancer can only be highly presumed based on many elements, including sex, age, isolated adenopathy, and histologic diagnosis of adenocarcinoma.

High estrogen or progesterone receptors levels found in the metastatic axillary nodes can help to confirm a primary breast tumor (29); however, three series (4, 30, 31) reported that 50% to 86% of occult breast cancer cases were found to be negative for estrogen receptors. Because surgical excision of the palpable node was often the first diagnostic procedure, rarely was an attempt made to analyze the receptors by biochemical methods. In a series of 80 patients with occult breast cancer and axillary metastases, Montagna et al. (32) performed the immunohistochemical analysis of estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR) receptors, and HER2 protein on the metastatic axillary nodes. They found that 46 (58%) were ER negative and PR negative (no expression), and 20 (25%) were HER2 positive. Using these as surrogate markers of biological subtypes, they found 14 (17.5%) luminal A (ER/PR positive, HER2 negative), 6 (7.5%) luminal B (ER/PR positive, HER2 positive, 28 (35%) HER2 enriched (ER and PR negative, HER2 positive), and 31 (39%) triple negative.

Natural History

After removal of an axillary adenopathy, a breast cancer eventually developed in the untreated breast in an average 42% of patients, as reported in one review (2), with time intervals below 5 years in all cases. Patient samples were limited in these series, however, and follow-up periods varied widely. In the Royal Marsden series (33), 10/13 patients (77%) who had negative breast imaging including mammography, ultrasound, and MRI, and no breast treatment, have recurred in the ipsilateral breast at 68 months median follow-up.

The number of pathologically involved lymph nodes seen after axillary dissection is high. Table 66-2 summarizes the results in five series, reporting a median number of involved nodes was close to three. Forty patients in the Institut Curie series had an axillary dissection as initial treatment. The median number of involved nodes was 3 (range, 1 to 20). During follow-up, 16 of the 59 patients in the series had distant metastases: 4 (25%) in the brain, 5 (31%) in the liver, 3 (19%) as cervical nodes, and 3 in multiple sites. One patient had isolated bone metastases. Ten patients had contralateral disease, which occurred in the contralateral breast alone in 6 patients. Of note, 4 patients had isolated contralateral axillary node metastases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree