- An evaluation of a person’s nutritional status is a key step in the management of malnutrition.

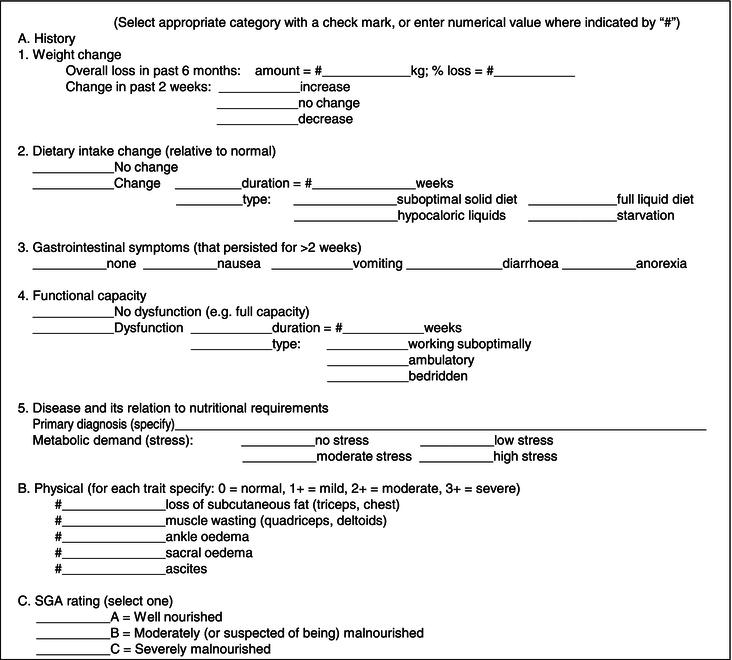

- Many screening instruments for malnutrition exist and the choice depends on the purpose for which they were designed, the target population, and the characteristics of the tools, such as reliability, validity, and user-friendliness. The use of the same consistent criteria within and between settings can facilitate care during the patient journey.

- In contrast to nutritional screening, which is a rapid procedure, often undertaken at the bedside or in the field, a more detailed nutritional assessment of nutritional status, including the status of individual nutrients, is more time-consuming and may involve a variety of different approaches, ranging from a detailed clinical and dietary history to a physical examination, and an array of investigations, ranging from body composition tests to laboratory measurements of nutrient concentrations in physiological fluids.

- The results of nutritional screening and assessments should be linked to a care plan, with clearly defined goals for treatment where appropriate, which should be re-evaluated at intervals.

2.1 Introduction

Considerable emphasis is placed on the identification of malnutrition, because it is the first step in the management of malnutrition. Ultimately, the aim is to provide effective treatment to individuals who need nutritional support and not to provide it to those who do not need it. Without identification, no effective treatment can occur. Inappropriate identification can be counterproductive, since treatment may be given to those who do not need it, and thus withheld from those who would stand to benefit from it.

For practical reasons, nutritional screening is often distinguished from nutritional assessment:

- Nutritional screening is a simple, quick, and general procedure used by nursing, medical, or other staff, often at first contact with a patient, to detect significant risk of nutritional problems, so that a clear action plan can be implemented. This may involve referral to a dietitian or another expert.

- Nutritional assessment is a more detailed and specific evaluation of a patient’s nutritional status, usually undertaken by an individual with some nutritional expertise (e.g. dietitian, clinician with an interest in nutrition or nutrition nurse specialist). Assessment is usually carried out when serious nutritional problems are identified by the screening process, or when there is uncertainty about the appropriate course of action. It allows specific nutritional care plans to be developed for individual patients. It can also be used to identify micronutrient status, although this frequently requires confirmation by laboratory investigations.

It is also useful to distinguish between a nutritional screening test and a screening programme:

- A screening test, typically a recognised screening tool or instrument, is the test used to identify a disease or a condition (e.g. malnutrition or obesity).

- A screening programme is the full range of activities from identification of risk using a screening test to definitive diagnosis and treatment of the disease or condition.

This chapter focuses predominantly on nutritional screening and assessment in adults, although the general principles also apply to children (for paediatric aspects, especially anthropometry, see Chapter 23).

2.2 Nutritional screening

The screening test (or screening tool) should be simple and quick to perform, valid and reliable, and acceptable to both patient and health worker. Ideally it should also be able to identify risk of malnutrition in those who are unconscious or confused, and in those in whom weight or height cannot be measured. Furthermore, a screening test that is portable will facilitate care during the patient journey. Use of multiple screening tests based on different principles during the patient journey, either within care settings (e.g. transfer of patients from one ward to another or from one hospital to another) or between care settings, can be confusing and counterproductive. Since nutritional problems exist in all care settings, there would be several practical advantages if the same screening principles could be applied to all types of patients by a range of care workers. These advantages include facilitation of audits, economic evaluations, and comparisons of malnutrition prevalence between different groups of patients using consistent criteria. Furthermore, screening tools that simultaneously address both under- and over-nutrition would help bridge the gap between clinical and public health nutrition. Some screening tools have been developed for very specific applications, but unless they have demonstrable advantages over more general tools, there is likely to be some resistance to adopting them for routine clinical care, especially in care settings where the target population forms only a small proportion of the total population. The need to use different screening tools for different population groups would increase organisational complexity.

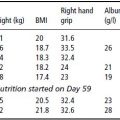

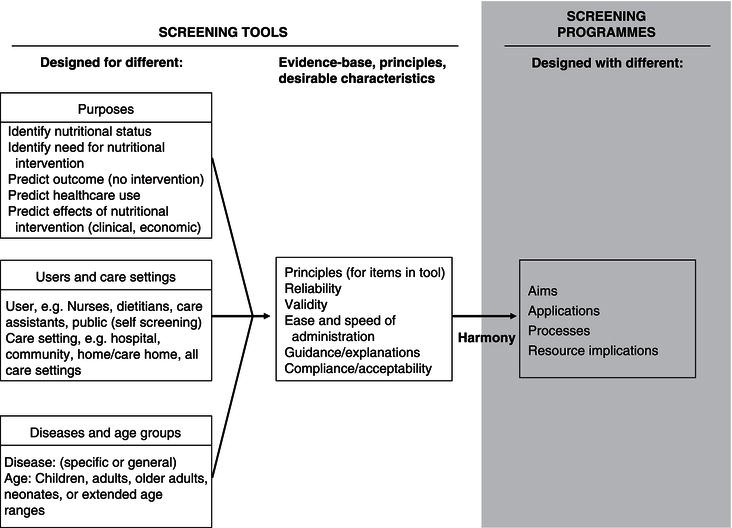

The choice of screening tool may not be easy, especially since some screening tools have poor agreement with others. There are a large number of screening instruments: some for children, others for adults, and some for both adults and children. In addition, many tools have been developed for use in specific subgroups of patients. Some adult screening tools have been specifically developed for older people and others for adults of all ages. Certain tools have been developed for particular care settings, such as hospitals and care homes, while others have been developed for all care settings. Some screening tools have been developed for use in specific clinical conditions, such as liver transplantation, renal dialysis, and learning difficulties, while others have been developed for all types of conditions. Screening tools have also been developed for use by specific healthcare workers, such as doctors (e.g. Subjective Global Assessment, SGA), nurses, or dietitians, or a combination of all three (e.g. the ‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’, ‘MUST’). Some have even been developed for members of the public, such as carers or the patients themselves, who are expected to self-screen (e.g. Screen I and II and DETERMINE). Some screening tools have been developed with other aims in mind, including: to identify nutritional status, to identify the need for nutritional intervention, to predict clinical outcomes without nutritional intervention, to predict healthcare use, and to predict clinical outcomes of nutritional interventions. This wide array of screening tools, coupled with the lack of a universally accepted definition for malnutrition and the wide variability between tools in validity, reliability, and ease of use, can create difficulties in choosing a screening tool that is fit for purpose. Figure 2.1 provides a framework for screening-tool selection that takes into account the aims, applications, and processes associated with particular screening tools, the principles on which they are based, and the overall purpose of the screening programme.

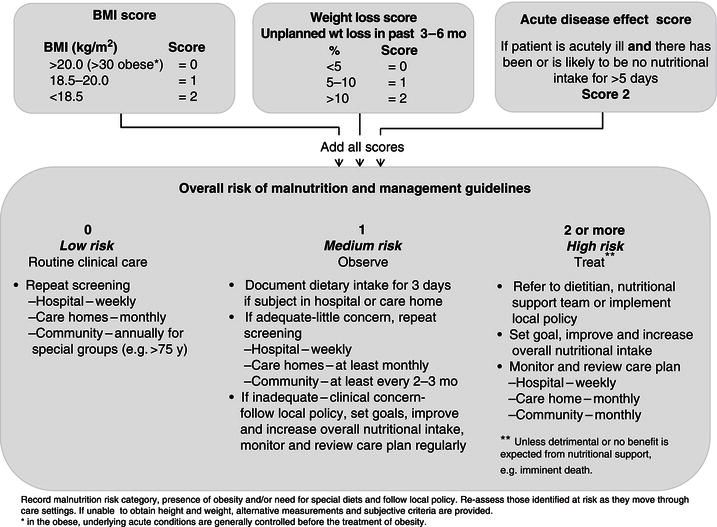

Although several examples of nutrition screening tools can be used to illustrate the underlying principles, details of only three are provided here (Subjective Global Assessment (SGA)) (Figure 2.2), Mini Nutritional Assessment (short form) (MNA, www.mna-elderly.com) (Figure 2.3), and ‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’ (‘MUST’, www.bapen.org.uk) (Figure 2.4). These were chosen partly because they are commonly cited or widely used, and partly because they illustrate the diversity of purpose and target populations. The SGA (Figure 2.2) was developed for use by clinicians in the late 1980s to predict clinical outcome without nutritional intervention, initially in hospitalised patients with gastrointestinal problems, and later in other groups of patients within the hospital setting. It is applicable to adults of all ages, although it may not be easy to administer for untrained nonmedical practitioners, who are required to identify certain signs including the presence of ascites and then integrate their overall findings into an overall subjective category of risk. Since it is a subjective tool, it does not involve measurement of weight or height. There is no clear guidance about how the results of the SGA are linked to a care plan. The MNA was developed in the early 1990s for use in older people (>65 years), and it is now used in different care settings. The original tool, with 18 items, took considerable time to complete (and as such can be regarded more like an assessment than a screening tool, according to the criteria indicated above), and over time shorter versions have been produced (Figure 2.3). If the short version of the tool indicates ‘possible malnutrition’ (‘malnutrition’ or ‘at risk of malnutrition’), it is recommended that a more detailed assessment be performed using the full version of the MNA. The tool involves measurement of weight and height to establish body mass index (BMI). A BMI <23 kg/m 2 contributes to the final malnutrition score (greater contributions to ‘possible malnutrition’ occur at BMI <21 kg/m 2 , and even greater contributions at BMI <19 kg/m2). The MNA was developed to establish nutritional status but, as with the SGA, clear guidance linking the results to a care plan is not provided. The ‘MUST’, developed in the UK, was launched in 2003 after field testing in over 200 centres. Its purpose was to establish the need for nutritional support according to nutritional status, including obesity, in adults of all ages in all care settings. Objective criteria, such as measurements of weight and height, are used whenever possible, and subjective criteria when necessary. The BMI cut-off point for malnutrition is <18.5 kg/m2 (or <20 kg/m2 for possible malnutrition in those without other criteria). BMI, together with the other two ‘MUST’ criteria (unintentional weight loss and an acute disease effect that has produced or is likely to produce no intake for more than 5 days), can be considered to represent a nutritional journey beginning in the past (history of weight loss), through the present (current weight status in the form of BMI), and continuing into the future (likely future weight change during the course of a disease) (Figure 2.4). This resonates with standard principles associated with establishing an overview of a patient in routine clinical practice. The tool can be administered by a variety of healthcare workers for clinical as well as public health purposes.

Figure 2.1 A framework for screening-tool selection. Reprinted from Elia & Stratton (2012), © BioMed Central.

Figure 2.2 Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) Detsky AS et al. J Parenter Enteral Nutr (Vol. 11, No. 1) pp. 8–13, copyright © 1987 by SAGE Publications. Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications.

Figure 2.3 Short-form Mini Nutritional Assessment (NMA) (Guigoz, 2006; Kaiser et al., 2009; Rubenstein et al., 2001; Vellas et al., 2006). ® Société des Produits Nestlé, S.A., Vevey, Switzerland; Trademark Owners © Nestlé, 1994, Revision 2009. N67200 12/99 10 M. For more information: www.mna-elderly.com.

Figure 2.4‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’ (‘MUST’). The ‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’ (‘MUST’) is adapted and reproduced here with the kind permission of BAPEN (British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition). For further information on ‘MUST’ see www.bapen.org.uk.

All of the aforementioned screening tools were developed for use in Western societies and therefore caution should be exercised in using them in developing countries with predominantly non-Caucasian populations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree