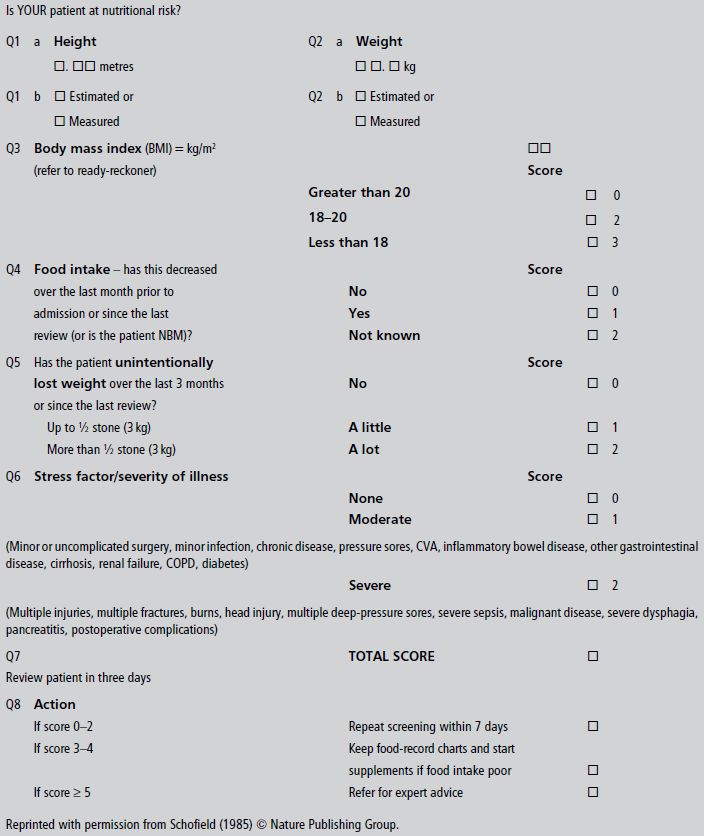

- A simple and rapid screening process, linked to an action plan, is the first step in alerting staff to the possibility that a patient is at nutritional risk.

- A patient who screens at risk may then need a more detailed and expert nutritional assessment, taking into account anthropometry, biochemistry and haematology, clinical picture, and dietary intake.

- The results of the nutritional assessment will determine the level of nutritional support or dietary counselling required and allow a clinical management plan to be developed.

25.1 Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to give the reader the opportunity to apply the knowledge gained from previous chapters to real clinical situations with all their challenging variety and interest. As in other branches of medicine, accurate diagnosis of nutritional problems, obtained from the full range of history, examination, and investigations, is the key to appropriate and successful treatment. Amidst the host of patients attending clinics, admitted as emergencies, or suffering the consequences of disease and its treatment, a large proportion have problems of nutritional excess, deficiency, or imbalance which affect their long-term health or the outcome of their current disease. A simple and rapid screening process, linked to action plans, is the first step in alerting staff to the possibility that the patient is at nutritional risk. You would be rightly criticised for failing to test urine or blood for glucose and missing the diagnosis of diabetes. The same principle applies to malnutrition.

A patient who screens at risk may then need a more detailed and expert assessment, leading to a clinical decision and management plan. This process will be applied to each of the patients described in this chapter, beginning with the screening tool we use for inpatients (Box 25.1) to identify those with actual or potential protein-energy deficit or excess. This addresses the following questions:

- Where is the patient now? Body mass index (BMI) or some surrogate such as mid-arm circumference (MAC).

- Where has the patient come from? Percentage weight change over the previous 3–6 months.

- Where is the patient going? This depends on change in appetite and food intake, as well as disease severity.

In addition, micronutrient deficiencies may be suspected from the history (e.g. alcoholism or restrictive diet), and other factors need to be considered at the extremes of life (e.g. growth velocity and development in children, and poor dentition, swallowing problems, and disability in the elderly). For these reasons, illustrative growth charts are included with Case 1 and the mini nutritional screening tool for the elderly with Case 3.

Further assessment will include not only nutritional requirements but the consequences of under-nutrition (e.g. muscle weakness) and over-nutrition (e.g. complications of obesity). A similar format will therefore be applied to each case, under the following headings:

- screening;

- nutritional assessment;

- problems to be addressed;

- clinical decision;

- nutritional requirements;

- treatment;

- monitoring and outcome;

- learning points.

Cases are grouped according to problem category.

25.2 Children

Case 1

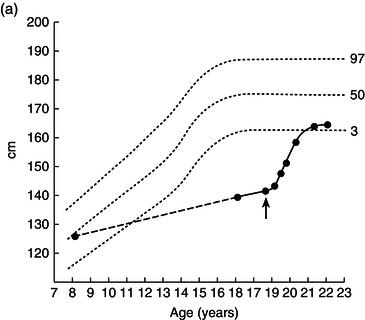

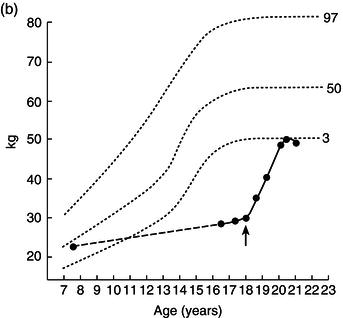

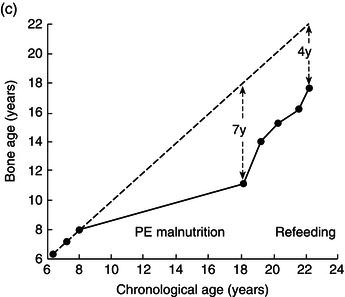

A healthy eight-year-old boy, in the 50th centile for height and weight, presented to the clinic feeling unwell with diarrhoea and abdominal pain after eating. Radiological and laboratory investigations led to a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, necessitating treatment with steroids and later with mesalazine and azathioprine. There was a series of exacerbations and remissions over the years. Between the ages of 8 and 17 years, his growth velocity fell to less than 2 cm per year, so that at the age of 17 he was below the third centile for height and weight, had no sexual development, and had a radiological bone age of only 12 years. Inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein (CRP) were raised and the serum albumin was low at 29 g/l.

Screening

Screening tools for adults are not so useful in the growing child, in whom changes in growth rate, development, and bone age are more useful. Nonetheless, at 17 years, with a BMI of 16.5 kg/m2, slight weight loss of 2% over 3 months, poor appetite and diminished food intake, and moderately severe disease, he still scored 6 on the tool in Box 25.1. Considered alongside the data on growth failure, this puts him at high nutritional risk.

Nutritional assessment

The history, examination, laboratory tests, and nutritional data at the age of 17 led to a clear diagnosis of disease-related malnutrition whose main manifestation was delayed growth and development. Previously, his doctors had focused on the treatment of the underlying disease process and had ascribed growth failure largely to this and the treatment with steroids and immunosuppressants. The doctor who saw him for the first time at the age of 17 realised that the effect of his disease on food intake and catabolic rate was the major cause of his growth failure and that this might be corrected by nutritional support.

Problems to be addressed

- Active Crohn’s disease, causing low food intake and increased catabolic rate.

- Anti-anabolic effects of steroids and immunosuppressants.

- Undernutrition, causing failure of growth and development.

Nutritional requirements

These should be calculated on the basis of his biological age of 12, the repair of nutritional deficit, and the needs for growth and development catch-up. His estimated requirements were 2630 kcal (11.0 MJ) and 65 g protein per day. It was also likely that he needed vitamin and mineral supplements, including vitamin D and calcium. Elemental diets (i.e. glucose and amino acids) were shown to have benefit in Crohn’s disease, but later studies have suggested that polymeric diets (oligosaccharides, fat, and whole protein) may be just as effective.

Treatment

In view of his anorexia, treatment began with the use of a nasogastric polymeric feed of 1000 kcal (4.2 MJ) and 70 g protein/l, starting slowly at 25 ml/hour and building gradually over a week to 100 ml/hour for 16 hours a day, allowing normal oral intake when desired. Once initial improvement had been obtained after 4 weeks, the nasogastric feed was discontinued and oral intake was continued using food of high energy and protein density, supported by proprietary oral supplements. The management of his underlying Crohn’s disease continued in the previous manner.

Monitoring and outcome

Height, weight, growth velocity, and sexual development were used as the main criteria of response to treatment (Figure 25.1). His growth velocity returned rapidly to normal and he regained some lost ground, reaching the fifth centile for height. This illustrates the phenomenon described by Widdowson in which, with delays in growth through malnutrition, renutrition may restore growth velocity, but the patient will never reach an ultimate height commensurate with genetic potential – remember the patient started at the 50th centile.

Figure 25.1 Illustrative growth charts for Case 1, showing (a) height, (b) weight, and (c) bone age compared to age.

Over the next 2 years he entered puberty, his bone age advanced, and his epiphyses closed with cessation of growth by the age of 20.

Learning points

- Failure of growth and development are the main manifestations of malnutrition in children.

- It is not always just the disease and its treatment that are responsible for the clinical manifestations of illness, but can also be the secondary malnutrition.

- Serum albumin is low because of inflammation and protein-losing enteropathy, rather than malnutrition (see later cases).

- Nutritional support, where appropriate, can be extremely effective and is an important part of management.

- Early diagnosis and treatment of malnutrition is essential if unnecessary loss of growth potential is to be prevented.

25.3 Anorexia of psychological origin and refeeding syndrome

Case 2

A young woman aged 22 had started to lose weight in her mid-teens, when anorexia nervosa was diagnosed. She was being followed up, appropriately, by a psychiatrist with a special experience in eating disorders. Her menstruation had ceased at the age of 16 as her BMI fell below 17 kg/m2. BMI continued in the range 15–17 kg/m2 until 6 months before admission, when her condition worsened. She became very weak and her family and carers feared for her life.

Screening

On admission, her height was 1.66 m and her weight 29 kg, giving a BMI of 11.0 kg/m2. Screening score was estimated at 7 and she was referred for more detailed assessment and for nutritional support.

Nutritional assessment

Life-threatening malnutrition. Life-saving artificial nutritional support indicated.

Problems to be addressed

- severe anorexia nervosa;

- life-threatening malnutrition.

Clinical decision

She agreed to accept nasogastric feeding. Since in the UK, legally, anorexia nervosa comes under the Mental Health Act, sectioning the patient and feeding under sedation, without the patient’s consent, is not only legal and ethical, but mandatory if the patient’s life is deemed to be at risk, since survival below a BMI of 10 kg/m2 in women is unusual.

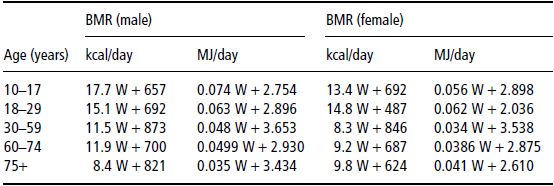

Nutritional requirements

Estimated resting energy expenditure (REE) (calculated by Schofield predictive equation, see Table 25.1) was 912 kcal (3.8 MJ), although with such severe malnutrition it might be 10–15% below this. Assuming 1.5 × REE for weight gain, the target intake should be approximately 1500 kcal (6.3 MJ) and 1.5 g protein/kg, or 45 g protein.

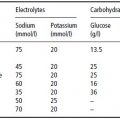

Table 25.1 Schofield equations for basal metabolic rate (BMR). W, weight in kg. Reprinted with permission from Schofield (1985) © Nature Publishing Group.

Treatment

An oral multivitamin preparation and folate were prescribed. A standard polymeric enteral feed of 4.2 kJ/ml was started at 30 ml/hour and increased to 60 ml/hour over the next 3 days. Oral intake was encouraged by day.

Monitoring and outcome

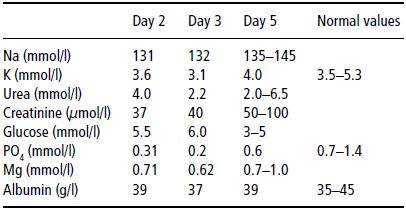

After 3 days of enteral feeding using a standard polymeric feed of 4.2 kJ/ml, starting at 50 ml/hour and increasing slowly to 80 ml/hour, she had gained 2 kg in weight and oedema was observed. At the same time, potassium and phosphate levels fell (see Table 25.2), necessitating intravenous supplementation with potassium phosphate.

After a week she became more active and lively, and after 3 weeks she was transferred to the psychiatric unit for further treatment, having gained 2 kg tissue weight without oedema. One of the long-term nutritional concerns was the development of osteoporosis associated with low oestrogen, malnutrition, and low calcium and vitamin D intake.

Learning points

The refeeding syndrome consists of (i) salt and water gain due to intolerance associated with severe malnutrition (famine oedema) and (ii) a fall in serum levels of potassium, phosphate, and sometimes magnesium due to anabolism of protein and glycogen causing cellular uptake (see also Chapter 3).

- Refeeding of severely malnourished patients should begin slowly for this reason. Diarrhoea may also be provoked with too-rapid oral or enteral refeeding.

- Careful biochemical monitoring during the initial period of refeeding is important.

- A BMI below 10 kg/m2 in women or 11 kg/m2 in men is usually fatal.

- Medico-legally, anorexic patients may be fed against their will in some countries, and this should be undertaken if life is at risk.

- Nutrition support only improves the patient’s physical condition and does not improve the basic psychiatric disease.

- Serum albumin is often normal in anorexic patients, unless there is intercurrent inflammation or dilution with retained fluid.

- Amenorrhoea usually occurs below a BMI of 17 kg/m2. Menstruation usually returns when the BMI rises above this level. With malnutrition, the hypothalamic release of luteinising hormone-releasing factor (LHRH) is reduced, and in both sexes gonadotropin and sex hormone levels are reduced.

- Low oestrogen levels with malnutrition and low calcium and vitamin D intake predispose to the early development of osteoporosis.

Table 25.2Biochemical changes with enteral nutrition (Case 2). On day 3, intravenous supplements were started with potassium phosphate. Note the low serum creatinine level, reflecting a low muscle mass.

25.4 Malnutrition in the older person

Case 3

A 73-year-old woman and her twin sister both developed thyrotoxicosis and lost weight due to the increased metabolic rate associated with that condition. The thyrotoxicosis was cured and the twin sister regained her normal weight. The patient, however, then developed severe depression and anorexia, leading to persistent weight loss. On admission to hospital she was cachectic, weak, and depressed, with bruising and oedema of the leg. She was severely depressed but a Mini-Mental score revealed no evidence of dementia. Her temperature was low at 35 °C. Her nutritional data are shown in Table 25.3.

Table 25.3 Nutritional data – Case 3.

| Height | 1.55 m |

| Weight Now Allowing for 3 kg oedema Remembered 2 years previously % weight loss | 36 kg 33 kg 51 kg 35% |

| BMI Now 2 years previously | 13.8 21.3 |

| Serum albumin | 41 g/l |

| Haemoglobin | 12.8 g/dl |

| Lymphocyte count | 0.51 (normal 1.5–4.0) × 109/l |

| Creatinine | 40 (normal 50–100) µmol/l |

| Urea | 1.5 mmol/l |

Screening

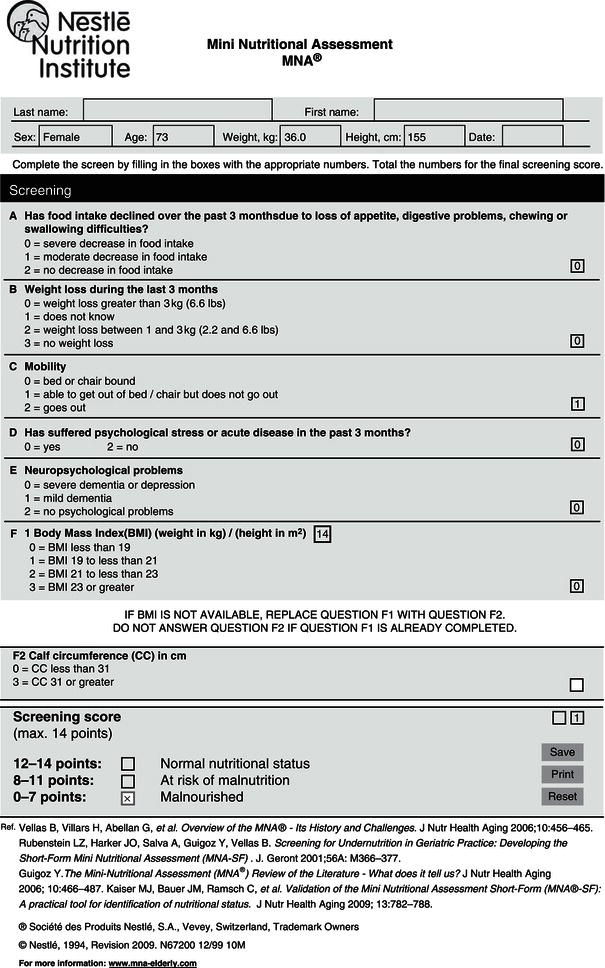

Figure 25.2 shows the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) validated for nutritional screening of the elderly and the scores for this particular patient. In contrast to the nutritional screening tool in Box 25.1, a low rather than a high score indicates malnutrition here, which in this case was severe.

Nutritional assessment

The screening tool was sufficient in this case to diagnose malnutrition. More detailed assessment showed profound loss of function. Not only does depression cause anorexia and weight loss, but more than 15–20% weight loss can itself cause depression, creating a vicious circle that requires not only antidepressants but nutritional support. The latter was particularly indicated in this case because few women survive a BMI below 10 kg/m2, or men below 11 kg/m2. Her low temperature and low lymphocyte counts were typical of the failure of thermoregulation and of immunity associated with severe weight loss. She had so-called ‘famine oedema’, since, with severe weight loss, the extracellular fluid volume as a percentage of body weight increases, and salt and water may be retained in excess.

Despite severe malnutrition, the serum albumin concentration was normal, in the absence of any inflammatory condition. The low blood urea reflected low protein turnover and the low creatinine her diminished muscle mass. Her food intake had been so poor in quantity and quality that multiple micronutrient deficiencies had to be presumed, which might account for some of the bruising on her legs. Measurement of vitamin and trace-element concentrations in blood are possible in specialised laboratories, but are not routine.

Figure 25.2 Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA). Rubenstein et al. (2001), Guigoz (2006), Vellas et al. (2006), Kaiser et al. (2009) ® Société des Produits Nestlé, S.A., Vevey, Switzerland, Trademark Owners. © Nestlé, 1994, Revision 2009. N67200 12/99 10M. For more information, visit www.mna-elderly.com.

Problems to be addressed

- Previous thyrotoxicosis and weight loss.

- Severe depression causing anorexia.

- Profound protein-energy malnutrition, exacerbating her depression and causing major functional impairment, including failure of the thermogenic response to cold or the febrile response to infection.

- Presumed multiple micronutrient deficiencies.

Clinical decision

Ethical considerations should always inform clinical decisions, particularly at the extremes of life. Ceasing to eat and drink is a feature of dying from whatever cause, and terminal dementing illness is no exception. Artificial nutritional support in such circumstances is contraindicated since it exposes the patient to all the risks and confers none of the benefits of the treatment (for the ethical principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence, see Chapter 10). This patient, however, had two major treatable and reversible conditions: depression and malnutrition. In addition to antidepressants, therefore, she required nasogastric feeding, since her anorexia precluded sufficient feeding by mouth. The patient’s permission was therefore obtained (the ethical principle of autonomy must be observed, except in anorexia nervosa) to pass a fine-bore nasogastric tube, whose position was ascertained radiologically.

Nutritional requirements

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree