537

Nutrition

Suzanne D. Gerdes

INTRODUCTION

Nutrition is important at any age to maintain health. Aging brings on lifestyle changes and physiological changes as well as an increase in chronic diseases such as heart disease, kidney disease, diabetes, and cancer. Maintaining nutritional status can become challenging when symptoms of diseases, side effects of treatments, or difficulty purchasing and preparing foods arise. Poor nutrition is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, decreased functional capacity, and a loss of independence. Therefore, identifying patients at nutritional risk is essential, as early intervention in the geriatric population can help to minimize unintended weight loss, malnutrition, sarcopenia, and cachexia associated with many chronic diseases.

UNINTENDED WEIGHT LOSS

Older adults often find it difficult to regain lost weight due to loss of appetite as well as illness, use of medications, chronic diseases, social changes, and physiological changes of aging.

Chemosensory changes in aging impair patients’ desire to eat (1). Older adults are more likely to incorrectly identify tastes than young adults (2) and poor vision lessens their sensory experience of eating, impacting their appetites (3). Poor dentition or use of dentures may also decrease sense of taste or make it more difficult to chew foods. Many medications decrease saliva production, impacting the sense of taste and smell of foods and leading to a loss of appetite (4).

Anorexia, present in 50% of patients with cancer, leads to unintentional weight loss. Hypercatabolism via proinflammatory cytokines plays a role in increasing muscle protein degradation, decreasing protein synthesis, and altering hunger hormones—leptin and ghrelin (4,5). As a result, not only is appetite lessened, but metabolic rate is also increased, thus increasing patients’ nutrient needs.

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract changes during the aging process, long-term use of medications, and surgery. The sensation of hunger lessens with aging. The slower rate of peristaltic action of the GI tract also contributes to satiety as a result of delayed gastric emptying (6). Medication-related constipation impacts older adults’ appetites as well (5). Cancer treatments such as radiation therapy, surgery, or complications may lead to esophagitis, reflux, or diarrhea. Adapted diets, including limiting patients’ 54food selections, are required in these situations either temporarily or permanently to minimize side effects and improve nutritional status.

MALNUTRITION

Malnutrition is defined as a lack of adequate energy intake or inadequate protein or other nutrient intake that is required for maintaining and repairing healthy tissues. The prevalence of malnutrition varies from 2% to 10% among older community-dwelling adults and from 30% to 60% in hospitalized older adults (7,8). It is expected that the prevalence is actually even higher, as malnutrition continues to be underreported. It is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, decreased function and quality of life, increased frequency of hospital admissions, and longer length of hospital stay (LOS) (7,9).

Nutrition Screening

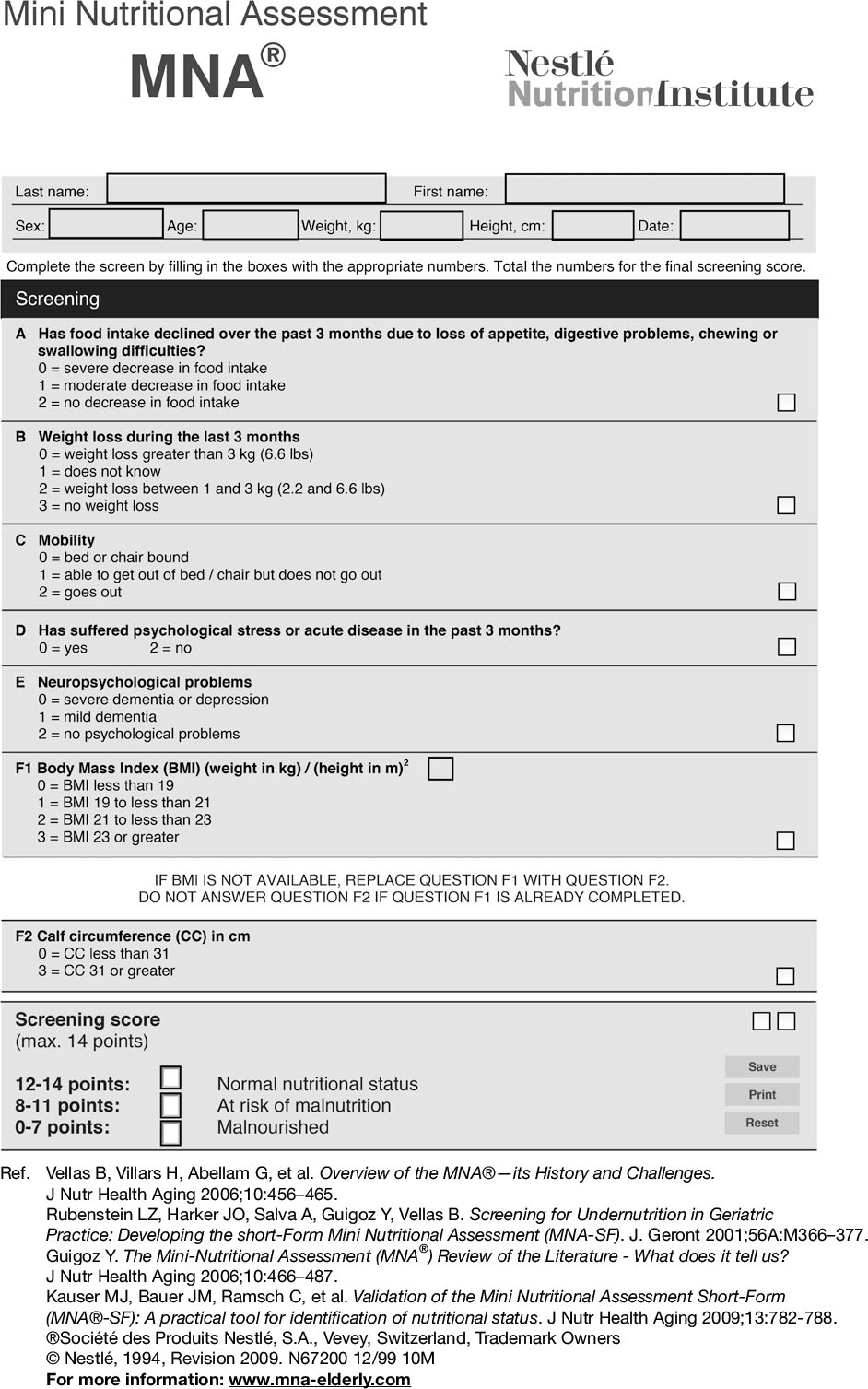

Timely nutrition screening is essential in identifying patients at risk for malnutrition. In the inpatient setting, the nutrition screen should be completed within 24 hours of admission. In the outpatient setting, the Joint Commission mandates that “nutritional screening may be performed at the first visit”; however, reassessment is done on an as-needed basis and when it is appropriate to the particular patient’s visit (10). Further assessment is required to diagnose malnutrition, but utilizing the past medical history and physical examinations help to raise suspicion of malnutrition. Several screening tools have been developed to help identify patients at risk of malnutrition. Studies find that the Mini Nutrition Assessment (MNA) (see Figure 7.1) is the best predictor of malnutrition in the older adult, in both inpatient and community-dwelling settings (14). The MNA is not a diagnostic tool, and further assessment should be completed soon after patients are screened.

Diagnosis of Malnutrition

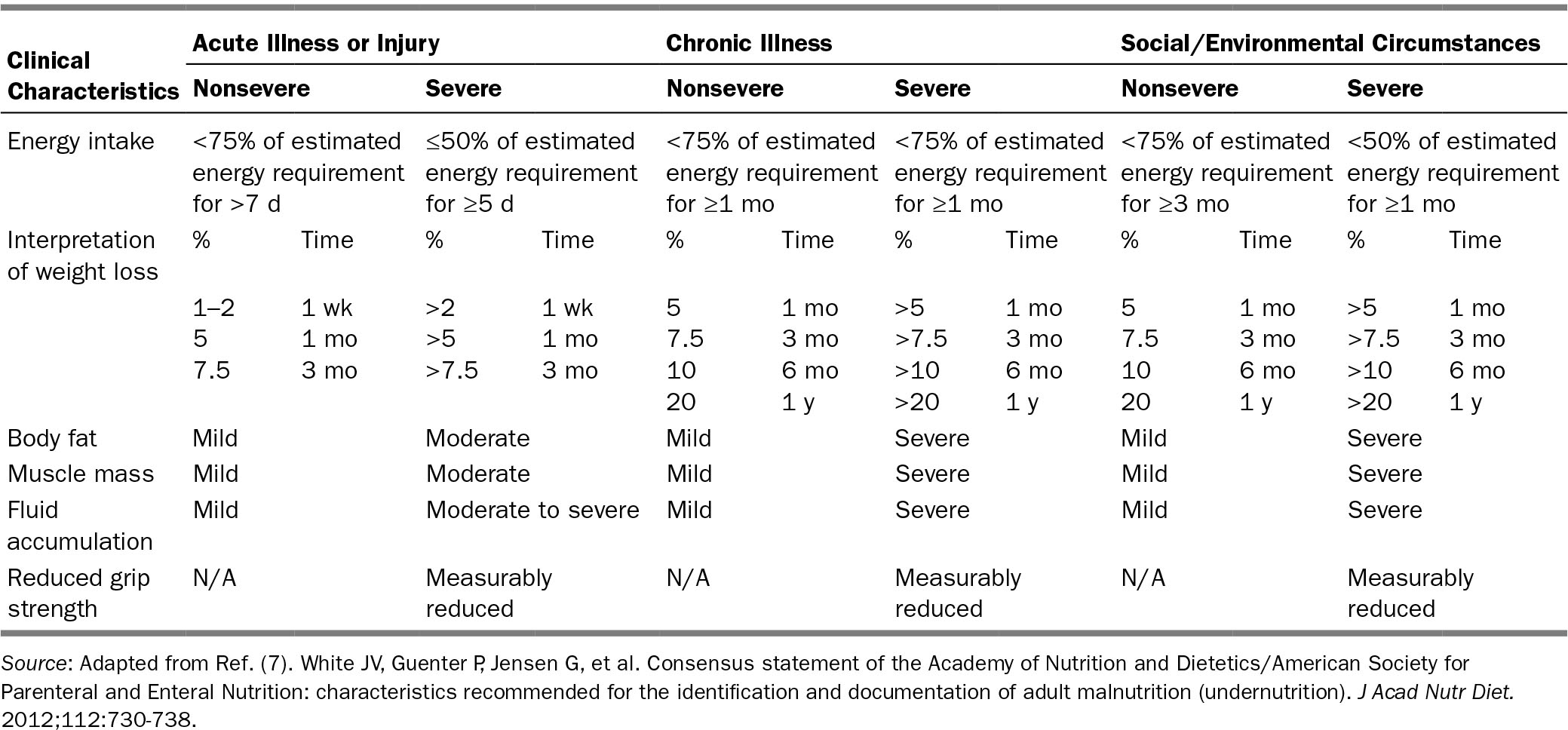

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) have worked together to create a standardized approach to the diagnosis of adult malnutrition (7). They identified several standardized characteristics as a means to identify malnutrition in adult patients. These characteristics are outlined in Table 7.1.

Laboratory data such as serum albumin (ALB) are poor indicators of nutritional status. ALB has a large body pool size with only 5% from daily hepatic synthesis (15). ALB also experiences frequent extravascular and intravascular space redistribution and is influenced by changes in plasma volume, as seen in dehydration or blood transfusions, and may be decreased due to the inflammatory response often seen in acute and chronic illness. Visceral proteins, including prealbumin (PAB), transferrin, retinol-binding protein, and C-reactive protein (CRP), while more sensitive than ALB, are also influenced by the inflammatory response and also fail to show consistent improvement with increasing nutrition. Therefore, serum proteins are of little benefit when assessing nutritional status. To ensure that patients are meeting their nutrient needs, patients should be reassessed at frequent intervals throughout their hospital stay.

55

FIGURE 7.1 Mini Nutrition Assessment—a screening tool for malnutrition.

Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia is defined as the age-related loss of muscle mass, combined with loss of strength, functionality, or both (16). Young adults’ body weight is 37% to 46% skeletal muscle. Toward the fourth decade of life, muscle mass begins to decline at the rate of about 1% muscle loss every year (9). Meanwhile, fat mass continues to accumulate and infiltrate muscle tissue. Sarcopenia increases the risk of disability by an estimated 27% due to a high rate of falls and fractures (17). Sarcopenia and malnutrition often occur together due to common causes such as cytokine production and poor nutrient intake (18). If assessments such as hand-grip dynamometry or the 4-m walking speed indicate sarcopenia, nutritional and physical activity interventions should be considered (9,17,18).

TABLE 7.1 AND/ASPEN Clinical Characteristics That the Clinician Can Obtain and Document to Support a Diagnosis of Malnutrition

56

57Cachexia

Cachexia differs from sarcopenia in that fat mass is also lost in addition to an accelerated loss of skeletal muscle mass and anorexia (19). Proinflammatory cytokines, in addition to other agents produced by tumors, are also implicated in cachexia (19,20). Nutritional interventions may improve the precachexia and cachexia stages. However, individuals in the refractory cachexia stage, characterized by active catabolism, low-performance status, and life expectancy of less than 3 months, are unlikely to benefit from nutritional interventions (21).

OPTIMIZING NUTRITION

Critically ill patients are at increased risk of malnutrition throughout their hospital stay, if there are extended periods of time spent nil per os (NPO), frequent disruptions in oral or enteral nutrition, or if patients had difficulty eating prior to hospitalization.

Oral Nutrition

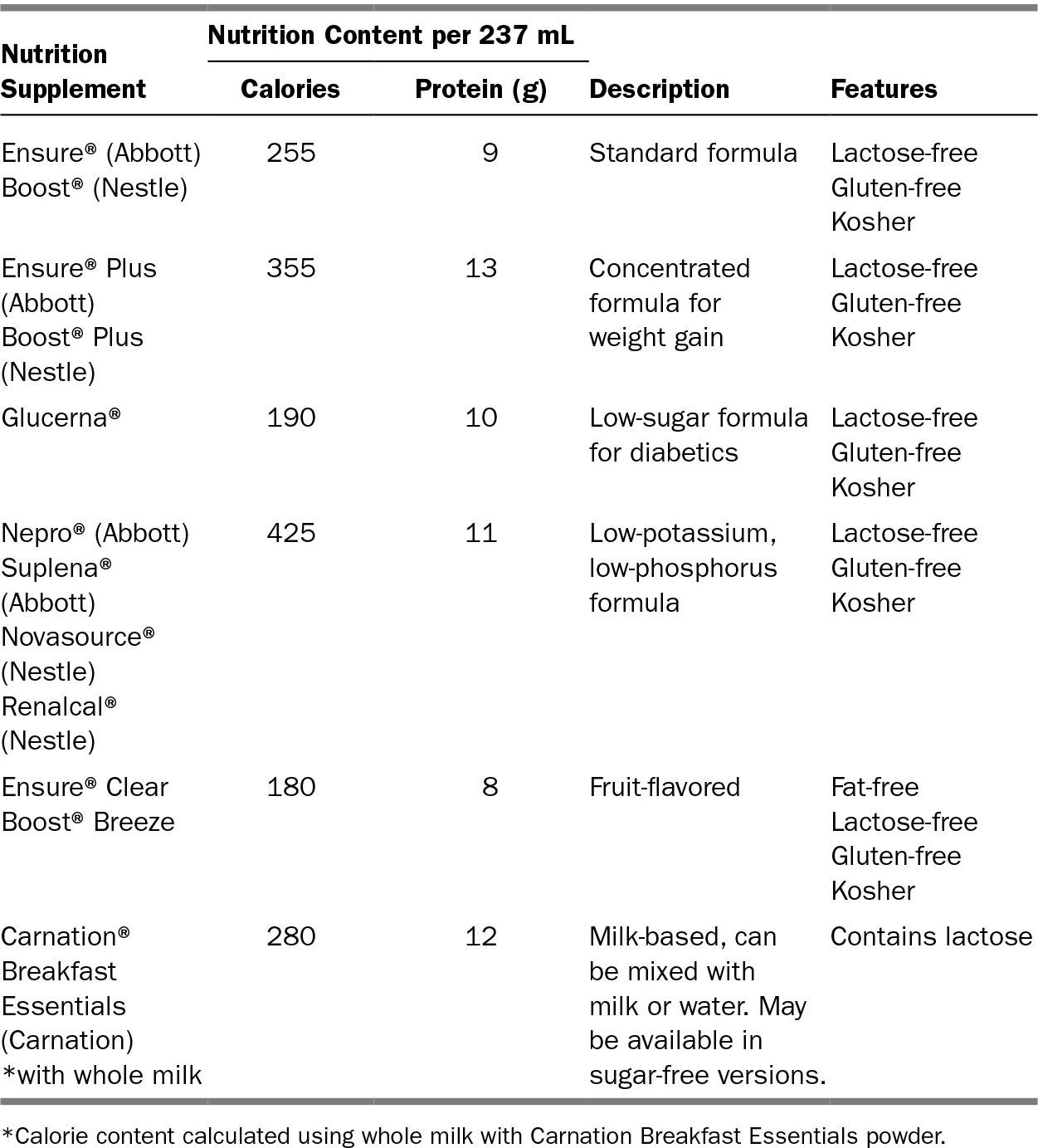

In all cases possible, NPO orders should be minimized. Older adults find that health and following a special diet are major barriers to eating adequate calories and protein (22). Diets should be liberalized and modified-texture diets should be provided when applicable. Additionally, losing the ability to shop for food greatly impacts older adults’ food selections. Community resources such as Meals on Wheels or programs through United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) can help to fill the gaps for older adults living in the community. Oral nutrition supplements may be helpful in increasing caloric and protein intake; examples are provided in Table 7.2.

Appetite Stimulants

In patients who are unable to meet their nutrition needs with nutritional intervention, appetite stimulants may aid in reducing anorexia and improving caloric intake. Medications that stimulate appetite include corticosteroids, progesterone analogs, cannabinoids, and serotonin antagonists. These agents work on various neuropeptides, neurotransmitters, and receptors in the hypothalamus, which help to improve appetite (23).Corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone, have been shown to be beneficial in improving appetite and managing symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and drowsiness (24). They are also associated with toxicities such as immunosuppression, glucose intolerance, decrease in muscle mass, and adrenal suppression (23). Progesterone analogs, like megestrol acetate, were developed as an appetite stimulant after finding that the medication had the side effect of weight gain (25). In comparison studies, megestrol acetate was superior to dexamethasone and the anabolic corticosteroid fluoxymesterone in measures of appetite (26). However, potentially serious side effects of 58progesterone analogs include edema, hot flashes, euphoria, glucose intolerance, exacerbation of arterial hypertension, and thromboembolism (25). The anabolic corticosteroid fluoxymesterone is used to stimulate muscle anabolism in athletes; however, there is a lack of research examining the role of progesterone analogs in older cancer patients (24). The mechanism of cannabinoids such as dronabinol, while poorly understood, is thought to suppress nausea and increase appetite. In studies of cancer patients, dronabinol did not significantly improve appetite or quality of life and was found to be inferior to megestrol acetate (27). Additionally, cannabinoids may cause delirium, dizziness, and ataxia. Cyproheptadine, a histamine and serotonin antagonist, is believed to counteract increased serotonin activity, thereby stimulating appetite. Its effects increased weight in patients with carcinoid syndrome. However, it may also lead to sedation (24). Other appetite stimulants, including mirtazapine, hydrazine sulfate, and olanzapine, lack evidence to support their routine use in cancer patients. Overall, in older cancer patients the risks and benefits of appetite stimulants 59must be weighed. Although these medications can enhance many patients’ perceived hunger sensations, appetite stimulants may be inappropriate in a population that is sensitive to change in mental status, immunosuppression, and declining muscle mass.

TABLE 7.2 Oral Nutrition Supplements Comparison

Artificial Nutrition Therapy

Artificial nutrition therapy should be considered for patients who are unable to meet their needs via an oral diet. Indications for enteral nutrition include inability to swallow, inadequate oral intake, acute pancreatitis, and high output proximal fistula. If malnourished patients are expected to have compromised ability to eat for a prolonged period of time, enteral nutrition is recommended (24). However, patients who present with terminal disease, including terminal dementia, are not recommended for feeding tube placement (28). The ethical implications, such as patient preference and religious positions, as well as benefits versus risks of placing feeding tubes, should be weighed prior to placement.

Parenteral nutrition should be considered in patients who are unable to absorb or ingest adequate nutrition when enteral nutrition is not feasible (24,29). It is recommended that severely malnourished patients receiving anticancer therapies and malnourished patients in the perioperative setting receive parenteral nutrition to treat and prevent nutrient deficiencies, limit adverse effects of anticancer therapies, or enhance compliance to therapies (24,29). Additionally, parenteral nutrition is appropriate in patients with severely compromised GI function, such as radiation enteritis, in which the cancer is well controlled. However, parenteral nutrition is not recommended in terminally ill patients. Studies suggest that if terminally ill patients experience hunger or thirst, it may be alleviated by feeding patients small amounts (24).

TAKE HOME POINTS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree