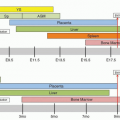

The most recent World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues

24 designates NHLs, including those predominant in the pediatric age group, according to their clinical, morphologic, immunophenotypic, and genetic features, and also acknowledges difficulties in differentiating some of the clinically significant subtypes of B-cell lymphoma by introducing some borderline (“gray-zone”) categories to encompass these issues.

Table 89.1 summarizes the pediatric NHLs according to the WHO Classification 2008.

Table 89.2 summarizes the main diagnostic immunophenotypic features of the most common subtypes of NHL encountered in this age group.

Lymphoblastic Lymphoma (T and B Lymphoblastic Lymphoma/Leukemia)

ALL and LBL are neoplasms of precursor B-cells or T-cells, characterized by immature (blastic) morphology and immunophenotype. At the pathologic and clinical levels, ALL and LBL appear to represent an overlapping continuum, with the distinction between these two processes being largely quantitative and arbitrary: cases involving at least 25% of the marrow cellularity are managed as ALL, while cases with less or no marrow involvement, are designated as LBL.

25,

26,

27 More recent studies have identified important differences in gene expression profiles, adhesion molecule expression, and molecular pathways of T-ALL and T-LBL that explain at least partially their distinct dissemination patterns.

28,

29,

30 T-LBL is the more common subtype and involves most often the mediastinum, lymph nodes, skin, bone, or soft tissues, and less commonly kidney, lung, or orbit. By contrast, the less common B-LBL more often presents in the lymph nodes, skin, bone, soft tissues, or breast, with mediastinal presentation being very uncommon.

31,

32,

33,

34,

35 The most frequent location of skin lesions in children is the scalp.

34,

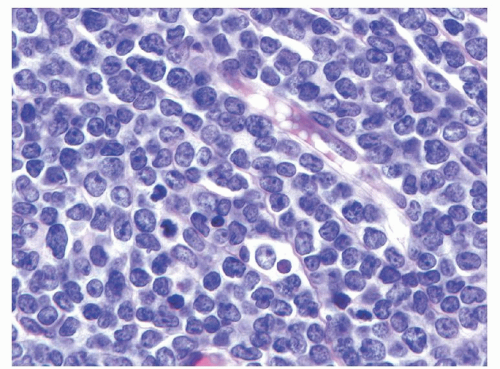

35Histologically, B- and T-LBLs show a diffuse growth pattern, with extensive replacement of the underlying normal tissue architecture by sheets of blastic cells. The malignant lymphoblasts are small to intermediate in size, with scant to moderate amounts of basophilic cytoplasm, finely dispersed nuclear chromatin, and small indistinct nucleoli (see

Fig. 89.1). In some cases the nuclei may have markedly irregular or convoluted outlines, a feature more common in T-LBL. Mitotic figures may be numerous in some cases, correlating with the presence of a “starry sky” appearance imparted by scattered pale macrophages containing apoptotic nuclear debris. BL should be considered in the differential diagnosis of such cases.

Immunophenotypically, approximately 90% of LBLs are of T lineage and the remaining 10% of B lineage.

36,

37,

38,

39,

40 Most T-LBLs resemble cortical thymocytes, a feature that may lead to difficulties in the differential diagnosis with thymoma and residual normal thymus in biopsy samples obtained from mediastinal and cervical lesions. They typically express CD1a, CD10, weak CD79a, BCL2, CD99, and the pan-T-cell antigens CD2, CD3 (mostly cytoplasmic), CD5, and CD7, although these markers may under- or overexpressed when compared to their normal counterparts. Similar to thymocytes, T-LBLs are often CD4

+ and CD8

+ and usually terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) positive, a marker that can be used to distinguish this neoplastic process from mature T-cell lymphomas.

41,

46 Other immature T-cell markers, including CD34 and HLA-DR are also coexpressed in these cases. A more frequent expression of T-cell receptor

αβ than

γδ has been reported in T-cell LBL as compared to precursor T-cell ALL.

47 Some LBLs may aberrantly express myeloid-associated antigens.

37,

48,

49 Of note, CD45 expression, often used to differentiate blasts by flow cytometry, ranges from dim (“blast-like”) to strong (“mature lymphocyte-like”) in T-ALL/LBL. A subset of T-LBLs resemble late thymocytes. In these cases TdT expression may be absent. They also express strong surface CD3, lack expression of CD1a, CD10, CD34, and HLA-DR, and are CD4

+ or CD8

+, rendering distinction from mature T-NHL very difficult, especially in small needle biopsy samples. The mediastinal localization and blastic cell morphology are very helpful in such cases.

B-LBLs typically resemble normal progenitor B-cells found primarily in the bone marrow and in lower numbers in blood, lymph nodes, and tonsils.

46,

50,

51 They express CD10, TdT, CD99, the B lineage antigens PAX-5 and CD79a, and may be negative or only weakly positive for the mature B-cell marker CD20. The neoplastic cells most often lack expression of surface IG and light chain restriction. Most often they express cytoplasmic

µ heavy chain without detectable

κ or

λ IG light chains.

38,

52,

53 Rare cases of B-LBL may express surface IG with light chain restriction, associated with strong CD20 expression and without detectable TdT; in such cases BL should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

39,

54 Of note, a significant proportion of pediatric B-ALL/LBL lack expression of CD45 (leukocyte common antigen), a marker often used to identify hematopoietic neoplasms in tissue

sections. This feature, combined with the frequent expression of CD99 by these neoplasms may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma, another CD99

+ pediatric neoplasm with blastic morphology, unless other markers (e.g., PAX5, TdT) are included in the diagnostic immunohistochemistry panels.

Cytogenetic studies of pediatric LBLs are few and include small numbers of patients (

Table 89.3).

55,

56,

57 Additionally, some reports of the cytogenetic or molecular genetics of LBL include cases of ALL with extra-medullary spread. T-LBL and T-ALL share similar chromosomal abnormalities. Chromosome abnormalities of the T cell receptor are relatively common and include chromosome abnormalities at 7q34-36, 7p15, and 14q11.

56,

57 The t(9;17) translocation appears more commonly in T-LBL than T-ALL.

56,

57 These patients often present with a mediastinal mass and have an aggressive disease course. The t(8;13)(p11;q11-14) has been described in rare cases of precursor T-LBL that present with myeloid hyperplasia and eosinophilia.

58,

59,

60The t(10;11) (p13-14;q14-21) is an uncommon but recurring translocation associated with T-ALL, and T-LBL, where it correlates with expression of the

γ/

δ T-cell receptor by the neoplastic cells.

61,

62,

63 Cytogenetic abnormalities have not been shown to be of prognostic significance in LBL. At the molecular level, B-LBLs and T-LBLs contain IG (IG) and T-cell receptor gene (TCR) rearrangements, respectively. The latter should not be used for lineage determination, as B-LBLs (like B-ALL) often contain TCR rearrangements, and T-LBLs may also harbor IG gene rearrangements.

Burkitt Lymphoma

The WHO Classification replaced “small noncleaved cell lymphoma” of the older NCI Working Formulation with BL (

Table 89.1),

9,

64,

65 and also combined under the same category the ALL-L3 of the French-American-British classification, which corresponded to cases of high-stage BL with leukemic dissemination.

BL is a mature B-cell lymphoma which resembles highly proliferative B-cells present in the follicular germinal center (GC). The biology of this lymphoma is characterized by translocations involving the

MYC gene and leading to its overexpression and the typical high proliferation rate. Notably, however,

MYC gene rearrangements are not unique to this subtype of mature B-cell lymphoma. Clinically, as described above (

see section “Epidemiology”) there are three recognized variants of BL: endemic, sporadic, and immunodeficiency-associated, which appear to correlate with distinct profiles of clinical presentation, association with EBV, molecular lesions, and cytogenetic abnormalities. Histologically, BL may present as one of three patterns with no prognostic significance (classic, atypical, and plasmacytoid), previously recognized as disease variants and currently merged under the unique designation of BL. Regardless of the histologic variant, BL is characterized by a diffuse growth pattern that typically replaces extensively the normal underlying tissue architecture. Occasionally, BL cells may also be seen “colonizing” preexisting GCs adjacent to the main tumor or present in the lymph nodes, draining an area involved by diffuse BL. Frequent mitotic and apoptotic cells are present and reflect this lymphoma’s high proliferative rate and apoptotic index,

respectively. Tingible body macrophages interspersed among the neoplastic cells impart a characteristic low-power microscopic “starry sky” appearance. The proliferation index, measured by immunohistochemical nuclear expression for Ki-67, typically approaches 100% of the tumor cells and is a requirement for the diagnosis of BL, regardless of the morphologic subtype, as an acceptable surrogate for the demonstration of

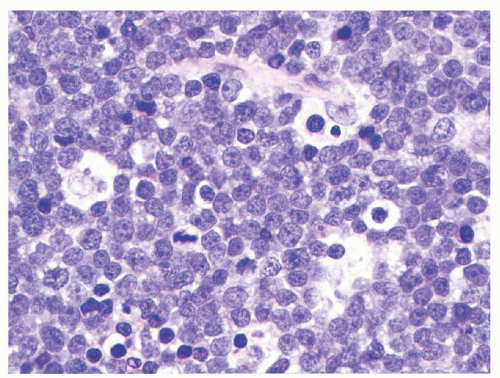

MYC gene rearrangements. In the classic BL variant the neoplastic cells are monomorphous, medium-sized (“small noncleaved”) with moderate amounts of basophilic cytoplasm (see

Fig. 89.2).

64,

65 The cells have round nuclei, clumped or condensed chromatin with clear parachromatin, and one to three nucleoli. When seen in Wrightstained cytologic preparations, BL cells have a characteristically deeply basophilic cytoplasm with prominent clear cytoplasmic vacuoles. In the atypical variant, the neoplastic cells are more pleomorphic, including large cells with centroblastic appearance and often prominent central nucleoli. The plasmacytoid BL cells, which are seen mostly in association with immunodeficiency, are more monomorphous, predominantly large, with eccentric nucleus, prominent nucleolus, and more abundant, IG-positive cytoplasm. BL cells retrieved from malignant pleural effusions often are larger and more pleomorphic than their tissue or blood counterparts.

Immunophenotypically, BLs have a mature GC-like profile. They express CD10, CD19, strong uniform CD20, CD22, CD79a, PAX5, BCL-6, and surface IG (IgM, or less commonly IgA or IgG), with IG light chain

κ or

λ restriction (

Table 89.2).

66 They are typically negative for BCL2, CD34, and TDT. The latter two antigens are useful in the differential diagnosis with B-LBL, which is most often positive for these markers. CD21, the receptor for complement fragment Cd3 and the Epstein-Barr virus, is more frequently detected in the endemic than sporadic form.

Cytogenetically, all cases of BL harbor one of three chromosomal translocations which rearrange the

MYC oncogene locus to regions controlled by regulatory components of the

IGH or light chain (

IGK or

IGL) genes, leading to constitutionally overexpressed

MYC in the neoplastic B-cells (

Table 89.3). These translocations include t(8;14)(q24;q32)/

MYC-IGH (80% to 90% of the cases), t(2;8)(q11;q32)/

IGL-MYC, and t(8;22)(q23;q11)/

MYC-IGK. The translocations associated with BL are relatively easily detected by classical cytogenetic methods and more recently by fluorescent in situ hybridization of interphase nuclei.

67 In addition to these classic translocations, a significant proportion of pediatric BLs also contain other nonspecific but recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities, some of which may correlate with prognosis, at least in cases with high-stage presentation.

68

Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma

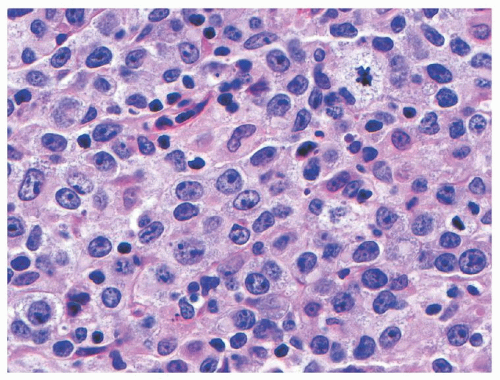

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) is a mature B-cell neoplasm composed predominantly of large cells (i.e., nuclear size equal to or exceeding that of macrophage nuclei), with a diffuse growth pattern, and with a proliferation index typically less than that required for a diagnosis of BL (typically 90% or less). The neoplastic cells may have a predominantly centroblastic (>80% in children),

69 immunoblastic (<10% in children),

69 or anaplastic appearance, defining three morphologic variants with no known prognostic implications (see

Fig. 89.3).

65 Tumors rich in T-lymphocytes and histocytes are defined as a distinct entity in the most recent WHO Classification as T-cell/histocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma.

Immunophenotypically, DLBCLs express one or more pan-B-associated markers CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, and PAX5. Surface or cytoplasmic IG are expressed by 50% or more cases. Some cases may express CD5, CD10, BCL2, BCL6, IRF4/MUM1, and CD30 (

Table 89.3). Gene expression profiling and immunohistochemical studies have defined subgroups with distinct biology in DLBCL. These groups do not currently determine therapy in children. The GC-like group, which is predominant in children

69 is characterized by a CD10

+/-, BCL6

+/-, IRF4/MUM1-immunophenotype, while the non-GC subtype is CD10

–, BCL6

+/- and IRF4/MUM1

+. Rare cases of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-expressing DLBCL with plasmablastic features can be found among DLBCL of children.

70,

71,

72 These have been included under the designation of ALK-positive large B-cell lymphoma in the WHO Classification 2008.

24Cytogenetics of DLBCL often include complex karyotypes with recurrent, but nonspecific abnormalities. While in adults many of the GC-like cases contain the t(14;18) characteristic for follicular lymphoma (FL), this is not the case in pediatrics, perhaps due to the unique biology of FL in this age group (see below).

69 The rare ALK-positive cases may harbor the t(2;5) or t(2;17), resulting in

ALK gene overexpression.

70,

71,

72

Primary Mediastinal (Thymic) Large B-cell Lymphoma

Primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) is an uncommon subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (<10% of large cell lymphomas in children) thought to arise from nonrecirculating thymic medullary B-cells.

65,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78 The latter feature may explain the biologic behavior of this tumor, which never involves the bone marrow (prerequisite feature for a diagnosis of PMBL and exclusion of DLBCL with secondary mediastinal involvement). Patients present with signs and symptoms of a large mediastinal mass, frequently with extension into adjacent structures including lung, pericardium, chest wall, and superior vena cava. Extrathoracic extension at diagnosis is uncommon but with disease progression can include kidneys, brain, soft tissue, skin, and adrenal glands. In the pediatric age group, the presence of extrathoracic disease at presentation is an adverse prognostic feature.

76Histologically, PMBL is characterized by a diffuse growth pattern and is composed of tumor cells that may range from mediumsized to large. They may have a centroblast-like appearance, may show lobated, “flower-like” nuclear outlines, or may have an anaplastic, Reed-Sternberg-like appearance. Often, they have abundant pale cytoplasm, with a “clear cell” appearance. The neoplastic cells are typically surrounded by thin to thick, dense fibrotic bands. Small benign-appearing lymphocytes and eosinophils may be present and add to the difficulty in differentiating PMBL from Hodgkin lymphoma.

Immunophenotypically, PMBL cells express CD45 and B-cell-associated antigens PAX5, CD19, CD20, CD22, and CD79a (

Table 89.2), characteristically lack IG, and very often show variable degrees of CD30 expression,

79 as well as CD23 and IRF4/MUM1 positivity. Expression of CD10, BCL-6, and BCL2 is less common. Although not unique to PMBL, the expression of the myelin and lymphocyte protein (MAL) may be useful in differentiating it from other mature B-cell and post-thymic T-cell lymphomas.

80Molecular studies uniformly reveal clonal IG gene rearrangements even if IG expression is not demonstrable by immunologic techniques. The lymphoma cells show mutated IG V region genes consistent with post-germinal center B-cells.

81,

82 Uncommonly, evidence of clonal EBV genome may be present in the tumor cells. The relatively few cytogenetic studies reported show aneuploid tumor cells, often with gains of chromosome 9p or Xq.

83,

84 The tumor cells may overexpress

REL or

MAL in a minority of cases.

85 BCL6, TP53, CDKN2A alterations and

MYC rearrangements may be present.

83,

84,

85,

86,

87

Unclassifiable Large B-cell Lymphomas

The most recent WHO Classification has recognized the existence of some borderline B-cell lymphomas, where complete morphologic, immunophenotypic, and genetic characterization does not allow a clear distinction between clinically significant categories of aggressive B-cell NHL or between DLBCL and classical Hodgkin lymphoma. This recognition has led to the definition of two heterogeneous disease categories that are not to be applied for cases where sufficient information is not available for a definitive distinction. These rare cases do occur in the pediatric age group and, at the present time, it appears that they are best managed as aggressive B-cell lymphomas in these patients.

B-cell Lymphoma, Unclassifiable, with Features Intermediate between Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma and Burkitt Lymphoma

This is a heterogeneous category of mature B-cell lymphomas, often with morphologic features of both DLBCL and BL, but with intermediate biologic features: cases of DLBCL with a gene expression profile similar to BL, many of which harbor dual translocations involving MYC and BCL2 (“double-hit lymphomas”), correlating with a particularly poor outcome; cases of DLBCL with high proliferation rate and immunophenotype resembling BL, but lacking a detectable MYC translocation; or cases with morphology typical for BL, but atypical immunophenotype or genetic features. Some of these cases would have been classified as “Burkitt-like lymphoma” in previous classification systems.

B-cell Lymphoma, Unclassifiable, with Features Intermediate between Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma and Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma

This category has been introduced mainly to reflect a distinct group of B-cell lymphomas occurring in the mediastinum and showing features intermediate between PMBL and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (“gray-zone lymphomas”).

88 However, lymphomas with similar features have also been described in peripheral lymph nodes. Gene expression profiling studies

have suggested related molecular signatures for PMBL and classical Hodgkin lymphoma,

89,

90,

91 offering a possible explanation for these phenotypically intermediate categories, although specific genomic studies of gray-zone lymphomas have not been reported.

Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

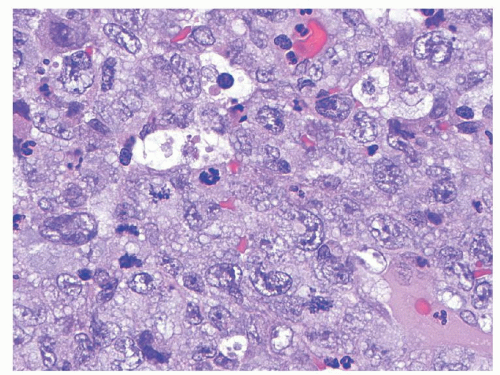

Anaplastic large cell lymphomas (ALCLs) are mature T lineage lymphomas characterized by anaplastic morphology (large “hallmark” neoplastic cells with abundant cytoplasm, pleomorphic, often horseshoe-shaped nuclei) and strong uniform expression of CD30. The most recent WHO Classification has recognized two distinct biologic entities sharing these features: ALK-positive ALCL and ALK-negative ALCL. The vast majority of pediatric ALCLs are ALK-positive and therefore, the latter disease subtype will be referred to exclusively in the remainder of this chapter. In children, ALCL tends to involve lymph nodes and extranodal sites including skin, soft tissues, lungs, and bones.

92 Approximately 20% to 25% of patients have bone marrow involvement at diagnosis that may not be obvious without ancillary studies.

93 Histologically, ALK expression by these lymphomas has allowed recognition of a wide spectrum of morphologic variants. These range from classical (common) cases, where the anaplastic cells predominate, growing in diffuse sheets (see

Fig. 89.4) or within sinusoidal lymph node space; to the small cell variant,

65,

94 where the anaplastic cells are a minor component, admixed with predominantly small neoplastic cells; and the lymphohistiocytic variant,

95,

96 containing a minority of “hallmark” cells surrounded by a reactive lymphohistiocytic population that forms the bulk of the tumor. The monomorphic variant, more common in children (author’s unpublished observation) consists of sheets of monotonous immunoblastic cells with a high mitotic rate and “starry sky” appearance, mimicking BL. Rare cases have a sarcomatoid appearance, consisting of spindled CD3

+/ALK

+/CD30

+ neoplastic cells. Although none of these variants appears to have prognostic implications, the small cell variant appears to be associated more often with systemic dissemination and leukemic peripheral blood involvement at presentation.

97,

103Immunophenotypically, ALCLs express one or more T-cell-associated antigens including CD2, CD3, CD4, CD7, CD43, or CD45RO (

Table 89.2).

65,

104 T-cell antigens CD5 and CD8 are usually negative. Some cases lack demonstrable T-cell antigens but have evidence of

TCR gene rearrangements.

65 Most ALCLs express cytoplasmic cytotoxic cell-associated proteins TIA-1, granzyme B, or perforin. A membranous and Golgi pattern of CD30 expression is characteristic of the neoplastic cells of ALCL.

105,

107 The most intense reactivity to CD30 antibodies is seen in the large cells, whereas the smaller cells are weakly positive or more often negative. Most ALCLs are positive for the EMA (epithelial membrane antigen) with a pattern similar to CD30.

108 Myeloid-associated antigens (CD13, CD15, CD33) are often expressed by neoplastic cells, especially when analyzed by flow cytometry.

109 Expression of myeloid markers CD13 and CD33 appears to differentiate ALK

+ ALCL from ALK- ALCL.

110Cytogenetically, the t(2;5)(p23;q35)/

NPM-ALK translocation is demonstrable in over 75% of ALK

+ ALCLs (

Table 89.3).

111,

112 Several other translocations involving the

ALK gene have been described, including t(1;2)(q25;p23), t(2;3)(p23;q21), inv(2) (p23q35), t(2;22), t(2;17)(p23;q11), and t(2;19)(p23;p13).

97,

113,

114,

115 All of these translocations lead to cytoplasmic overexpression and activation/phosphorylation of the

ALK gene product as a result of dimerization of the gene partner-associated proteins. The NPM-ALK fusion is unique in that it is associated with both nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of ALK, due to the unique nuclear localization properties of NPM (nucleophosmin). As a result ALCLs associated with this translocation show nuclear and cytoplasmic ALK expression, while all other tumors show cytoplasmic ALK only, allowing immunohistochemical staining for ALK to predict the underlying genetic lesion in these lymphomas.

Of note, ALK expression is not unique to ALCL, but has also been demonstrated in a large subset of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors, a predominantly pediatric mesenchymal neoplasm that also harbors translocations involving

ALK; as well as in other pediatric tumors, where alternative mechanisms of overexpression may be operative.

116,

117,

118 Therefore, careful immunophenotypic characterization of ALK

+ neoplasms should be performed to confirm the diagnosis of ALCL.