Age, Race, and Sex Differences

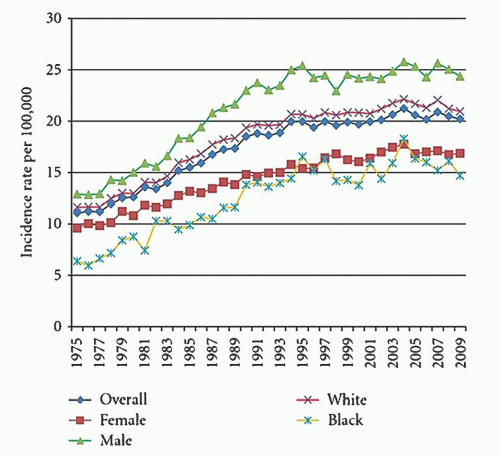

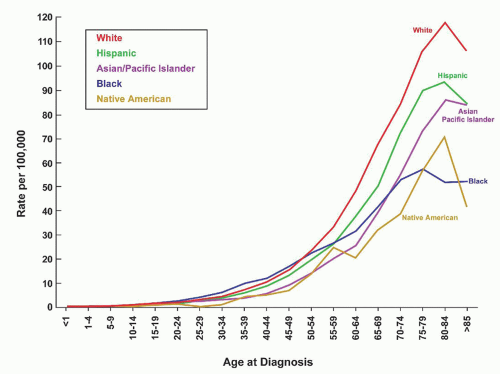

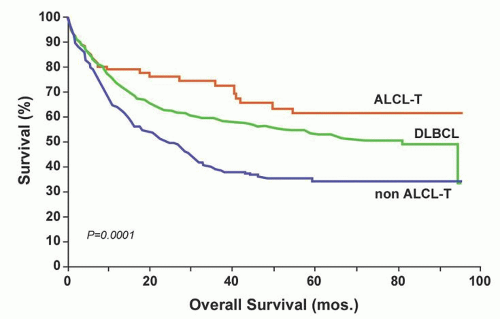

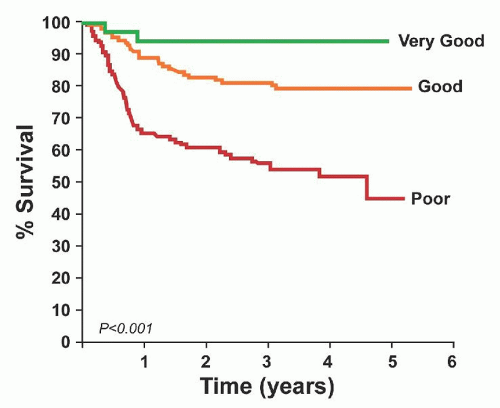

The frequency of various lymphoid neoplasms is age-dependent, has a variable worldwide distribution, and is more common in males than females. Lymphomas represent approximately 10% of all childhood cancers in developed countries and are third in relative frequency behind acute leukemias and brain tumors. They are more common in adults than in children and have a steady increase in incidence from childhood through age 80 years (

Fig. 88.3).

33 They are the fifth most common cancer in the United States and represent 4% of all cancers. The mean age at diagnosis is 45 to 55 years and the median age for 2005 to 2009 was 66 years. The annual incidence rate of NHL in 2005 to 2009 was 40% higher for males (23.8 per 100,000) than females (16.3 per 100,000). The median age of death was 75 years of age. The highest age-adjusted mortality in 2009 was in white males (8.7 per 100,000) and the lowest mortality has been in Asian/Pacific Islander females (3.4 per 100,000).

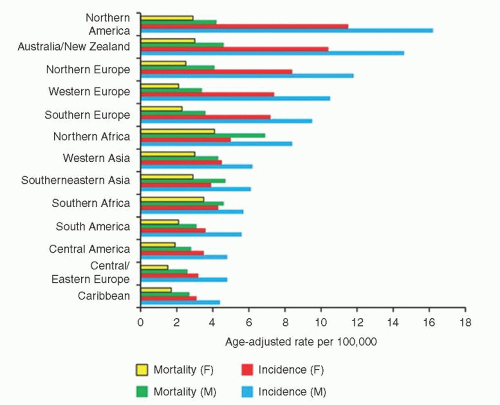

33 The incidence and mortality rates for NHL vary worldwide, with North America having the highest (

Fig. 88.4).

A comparison of NHL in children and adults is outlined in

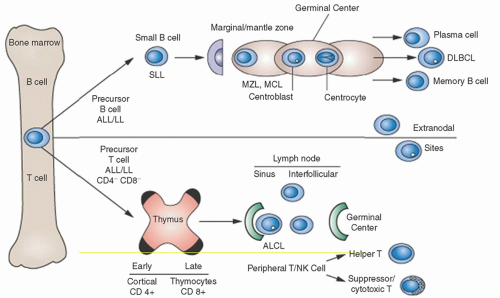

Table 88.2. Lymphomas involving peripheral lymph nodes are usually of B cell origin in North America and Europe and are more common in adults than in children, who often present with gastrointestinal involvement (BL) or mediastinal widening (usually lymphoblastic lymphoma of T cell origin). The histologic appearance of NHL is more variable in adults, who frequently have low grade follicular or diffuse patterns in which the majority of malignant cells are small, dormant lymphocytes; children predominantly have high-grade diffuse patterns in which the malignant cells have a “blastic” or transformed appearance and a high mitotic rate. A possible explanation of the differences between childhood and adult NHL is that most childhood lymphomas arise from early cells that are antigen-independent, whereas many adult lymphomas arise from fully differentiated cells and are antigen-dependent.

Extranodal presentation of NHL occurs in 15% to 25% of adult patients in the United States, is higher in Europe, and is up to 40% to 50% in Asia.

34 Clinicopathologic features of the epidemic of NHL include a faster rise in extranodal than nodal disease, an increase in diffuse pattern over nodular, and in aggressive NHL than in indolent disease.

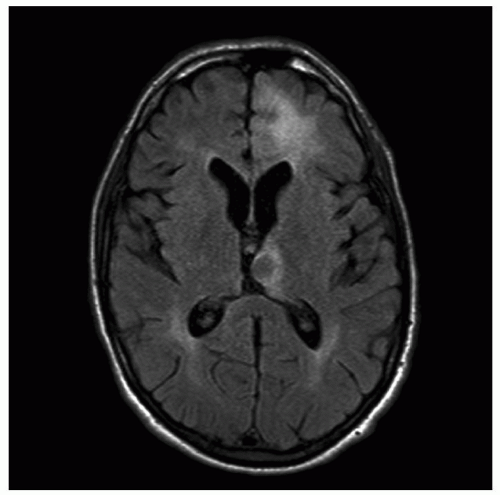

35 NHL of the brain has risen 4 times as rapidly as other extranodal sites and is partly due to AIDS, but the upward trend began before the AIDS crisis and continues to rise in immunocompetent hosts of all ages and in both genders.

36 The most common extranodal sites are the gastrointestinal tract and nasopharynx; other common sites include brain, skin, bone, thyroid, salivary glands, and testis.

Familial aggregation of NHL plays a small role in the epidemic and accounts for a 1.5- to 4-fold increased risk for NHL in close relatives of patients with lymphoma or other hematopoietic neoplasm.

37 Aggregation has been reported to be stronger for siblings and male relatives.

38,

39 Anticipation (earlier age of onset in subsequent generations) has been reported in NHL;

40 however, others have disputed the finding by suggesting that the studies do not account for the increasing incidence of NHL.

41There is an increased risk for both NHL and HL in families with an autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS, also known as the Canale-Smith syndrome), which is characterized by chronic lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, autoimmune features, and expanded T cells, negative for CD4 and CD8.

42 Both NHL and HL, particularly nodular lymphocyte-predominant, may occur decades after recognition of the syndrome and are associated with germline

FAS mutations and defective lymphocyte apoptosis. Somatic

FAS mutations and

CASP10 germline mutations are other subtypes of ALPS.

43A prior history of cancer, Jewish ancestry, and small size families have been suggested as risk factors for lymphoma.

44 In families with a diagnosis of NHL, there are reports indicating an increased risk for melanoma and other cancers, including pancreas and stomach.

38 Patients who have both a family history of hematologic cancer and occupational exposures to certain substances (e.g., gasoline or benzene) appear to have an increased risk for NHL.

45

Infectious Agents

Infectious diseases have contributed to understanding the mechanisms of lymphomagenesis. The role infections play in specific lymphomas vary according to host factors, environment,

and geography.

46 There are at least two mechanisms in which infections contribute to lymphomagenesis. The best described is direct lymphocyte transformation by microbial agents. Lymphotropic viruses include Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human T-leukemia virus-1 (HTLV-1), and human herpes virus 8 (HHV8). An alternative mechanism is an agent, such as

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), infecting host tissues and eliciting a lymphoproliferation response that remains dependent upon the presence of the agent, or antigen. The former does not usually respond to antimicrobial therapy, while the latter does. There are an expanding number of infections associated with specific types of NHL (

Table 88.3).

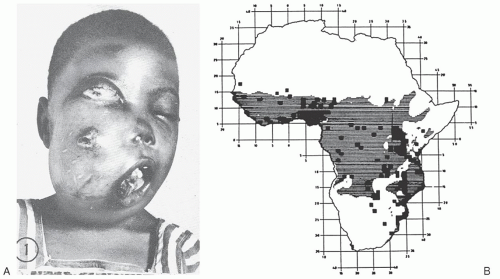

The complex interplay of environmental and host factors in the pathogenesis of lymphoma was recognized through Dennis Burkitt’s description in 1958 of an aggressive tumor of young children that was characterized by frequent jaw and abdominal involvement (

Fig. 88.5A). Using careful epidemiologic surveys, Burkitt identified a tumor belt across equatorial Africa that was associated with temperature, rainfall, and elevation (

Fig. 88.5B).

47,

48 Subsequently, the geographic distribution of this neoplasm was shown to correlate with that of endemic malaria. In 1964, Epstein, Achong, and Barr found viral particles in tumor cell lines derived from Burkitt’s patients.

10 A direct causative role for the virus was subsequently questioned by its infrequency in BL occurring outside Africa; however, the EBV was shown to be trophic for B cells, to induce B cell proliferation and differentiation, and to be the etiologic agent for infectious mononucleosis. In 1965, Burkitt was the first to discover that the lymphoma could be cured with chemotherapy.

49The identification of a 14q+ cytogenetic abnormality in BL by Manalov and Manalova

50 in 1971 led to the description of the 8;14 chromosomal translocation by Zech

19 in 1976. Subsequent molecular genetic studies showed that this translocation juxtaposed the

MYC oncogene on chromosome 8 to the

IG heavy chain gene sequences on chromosome 14.

51 These observations suggest that the 8;14 translocation of endemic Burkitt NHL arises in a state of EBV-induced polyclonal B cell proliferation in the setting of immunodeficiency associated with chronic malaria.

52 Support for this theory has been derived by the role of EBV in lymphoproliferation in other immunodeficient conditions. EBV has also been implicated in posttransplant lymphomas, AIDS-related lymphomas (mostly central nervous system [CNS] and variably with systemic), some T/NK lymphomas, particularly nasal; some HL, and several lymphomas that developed after chronic infectious mononucleosis.

53,

54,

55Shortly after immunologic classifications for NHL were proposed, adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) was described in Japan by Takatsuki and Uchiyama in 1977.

56 The clinical course of ATL was variable, but the majority of patients presented with an acute form, which was characterized by lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, skin lesions, hypercalcemia, and an elevated white count with multilobated lymphocytes, referred to as “cloverleaf” or “flower” cells (see

Fig. 88.21D), and a rapidly fatal course. In 1980 to 1982, Poiesz et al. in Gallo’s lab in the United States and

Yoshida et al. in Hinuma’s lab in Japan independently discovered an unique retrovirus, HTLV-1, as the etiologic agent of ATL.

57,

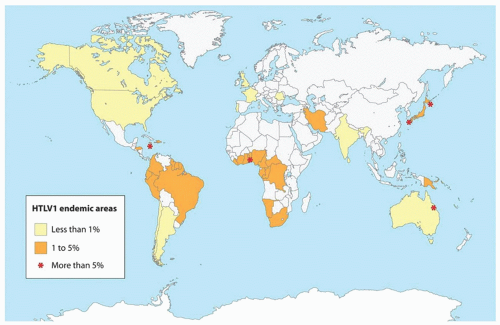

58 HTLV-1 was shown to be endemic to certain geographic areas: southwestern Japan, in which 6% to 20% of the population is seropositive for HTLV-1; the Caribbean Islands, New Guinea, parts of Central Africa and South America, parts of West Africa, the Middle East and Melanesia (

Fig. 88.6).

59,

60HTLV-1 is an RNA-containing delta retrovirus that infects mature T cells, usually CD3

+, CD4

+, and HLA-DR

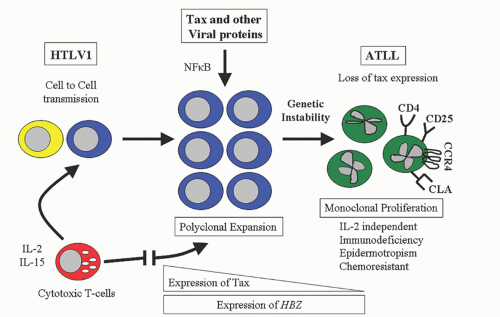

+. The molecular pathogenesis revolves around TAX, a potent HTLV-1 transcription activator protein, and HTLV-1 basic ZIP factor, HBZ (

Fig. 88.7).

59 T cell dysregulation may initially involve an autocrine interleukin (IL)-2 loop as well as paracrine effects from other cellular genes and cytokines. The TAX protein is prominent during the initial infection by increasing the expression of viral genes through viral long terminal repeats (LTRs) and by stimulating the transcription of cellular genes through signaling pathways of nuclear factor Kappa B (NF

κB), serum response factor (SRF), cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB), and activated protein 1 (AP1).

59 The TAX protein induces proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of HTLV-1 cells through induction of I

κB-alpha degradation, which activates the NF

κB pathway, which in turn promotes expression of cell-cycle regulators (cyclin D2 and CD

κ6) and leads to increased activation of PI3-kinase signaling.

61 TAX deregulates the expression of cytokines (IL-2 and IL-15) and antiapoptotic genes

, upregulates vascular cell adhesion molecules, activates osteoclasts, and alters interferon signaling, all of which contribute to the pathogenesis of ATL.

HBZ is transcribed from the 3′-LTR and is the only gene which is conserved and unmethylated in all ATL cases, while the

TAX gene is often inactivated by epigenetic changes or the loss of 5′-LTR.

62 Unlike TAX, which activates both the classical and alternative NF

κB pathways and suppresses TGF-

β signaling, HBZ suppresses the classical pathway without inhibiting alternative NF

κB signaling and promotes TGF-

β signaling, which leads to upregulation of forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) protein. By enhancing TGF-

β and increasing FOXP3 expression, HBZ allows infected T cells to convert to Tregs, which contribute to viral persistence and leukemogenesis.

HBZ promotes T cell proliferation in its RNA form by the regulation of E2F transcription factor 1 pathway; the HBZ protein interacts with CREB-2 and suppresses TAX-mediated viral transcription.

62,

63 Initially, the T lymphoproliferation is polyclonal and controlled by host defense mechanisms;

64 however, as TAX expression diminishes, an oligoclonal or monoclonal T cell proliferation that is IL-2-independent emerges, resulting in the clinical manifestations of ATL. HTLV-1 contributes to a multistep process of worsening genetic instability characterized by mutation of

TP53, deletion of tumor suppressor genes

CDKN2B/

p15 and

CDKN2A/p16, and DNA methylation.

59

HTLV-I can be transmitted by blood transfusions, needle sharing, sexual intercourse, and from mother to child through breast milk or through the placenta. Over 20 million people worldwide are estimated to be infected with HTLV-1, and over 90% will remain asymptomatic carriers.

60 The virus can have a prolonged latency period of decades before clinical syndromes appear

64,

65 (

see section on “Mature T/NK Leukemias”). Where the virus is endemic, ATL occurs at a rate of 20 to 86 cases per 100,000 population per year, with a lifetime risk of approximately 1% to 6% for those persons seropositive for HTLV-I antibodies.

64 In Japan, males are 3 times more likely to develop ATLL than females, with a peak age around 60 years, while in the Caribbean there is no gender difference and the peak age is 40 years.

66HTLV-I infection induces the production of antibodies to various viral core proteins which can be used as serologic markers of infection.

67 The diagnosis is usually suggested by a screening enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay and confirmed by Western blot. Because of slow replication, seroconversion may take up to 2 years in HTLV-I infection compared to the 3 to 6 months for HIV. PCR utilizes primers and probes of the Pol (polymerase or reverse transcripter) and TAX (transactivator) regions and is the most sensitive and specific assay for detecting HTLV-I. HTLV-I can lead to other diseases, including myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis, uveitis, bronchopneumopathy, and arthropathy.

60,

67Other viruses have been implicated in lymphoid neoplasia and include HTLV-II, herpes virus (HHV-6), HHV-8, (Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virus [KSHV]), and hepatitis B and C. HTLV-2 was isolated in 1982 by Kalyanaraman et al. from a

patient with an unusual T cell variant of hairy cell leukemia.

68 It has subsequently been isolated only rarely in lymphoid neoplasia and in HTLV-I negative tropical spastic paraparesis, but it is prevalent in intravenous drug abusers.

69 Two other related viruses, HTLV-3 and HTLV-4, were reported in 2005 in Central Africa but have not been linked to human disease.

70 Salahuddin et al. identified HHV-6 in B lymphocytes from 6 patients with various lymphoproliferative disorders;

71 it was identified subsequently as the etiologic agent for exanthem subitum (roseola infantum) and as a cause for pneumonia in immunocompromised hosts.

72 A role for HTLV-2 or HHV6 in lymphoproliferation has not been detected. KSHV, also referred to as HHV-8, has been identified in AIDS-related body-cavity based B cell lymphomas and multicentric Castleman disease and has been associated with EBV genome in the absence of

MYC rearrangement.

73,

74 Theoretically, KSHV acts synergistically with EBV to transform B cells and causes a unique clinical presentation.

There is conflicting data regarding the risk of NHL in patients infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV), but the association appears valid, particularly in endemic areas. Meta-analyses have reported a 2- to 3- and a 2- to 4-fold risk of developing NHL in HBV and HCV-infected patients, respectively.

75,

76,

77,

78 The incubation time for lymphoma to occur in patients infected with hepatitis is estimated to be as long as 15 years.

79 DLBCL is the most common subtype associated with HBV.

75 Besides the association of HBV with NHL, cytotoxic therapy with or without rituximab can lead to HBV reactivation, resulting in hepatitis and even liver failure.

78,

80 Screening HBV status prior to chemotherapy and prophylaxis with antiviral therapy for positive patients can decrease the rate of reactivation.

81The causative fraction of NHL by HCV varies widely according to country, but is estimated to be as high as 10% where HCV is endemic, such as Egypt, Italy, and South Korea.

82 Chronic HCV infection is often (40% to 90%) present in patients with type II mixed cryoglobulinemia (MC); and 5% to 10% of MC patients have or will develop a B cell lymphoma (see

Chapter 101).

83,

84,

85 Early studies stating that indolent B cell lymphomas, lymphoplasmacytic and marginal zone, were the most common subtypes associated with HCV have not been confirmed, but they were reported mainly in patients with MC who do have an increased risk for indolent lymphomas.

76,

86 Spleen involvement is more common in DLBCL with HCV (34% vs. 13%); some of the DLBCL have undergone transformation from an indolent NHL.

87 Rearrangement of either

IGH or the

BCL2 genes occurs in up to three-fourths of patients with HCV and MC and can regress with antiviral therapy.

88 Complete responses to antiviral therapy, primarily peg-interferon and ribavirin, occur in 60% to 75% of patients with HCV-positive lymphomas.

89,

90,

91 Adding rituximab to antiviral therapy is well tolerated and improves responses.

92,

93 Proposed mechanisms of HCV’s role in lymphomagenesis include chronic antigenic stimulation, activation of B cells by an HCV E2 protein, and direct infection of B cells, a combination of which could lead to genetic aberrations.

76,

85H. pylori is a gram-negative rod which was discovered by Warren and Marshall in 1983 and was shown to be associated with peptic ulcer disease, gastric carcinoma, and NHL.

94,

95,

96 Gastric lymphoma was found to have a high frequency in certain parts of Europe, such as the Veneto region of Italy, and was usually an indolent B cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALToma), a term proposed by Isaacson and Wright.

97,

98 Parsonett recognized that

H. pylori infection preceded the development of lymphoma,

99 and Wotherspoon reported in 1993 that antibiotic treatment for

H. pylori caused regression of the lymphoma in over two-thirds of patients.

100 Over one-half of

H.

pylori large B cell gastric lymphoma will also respond to antibiotics.

101

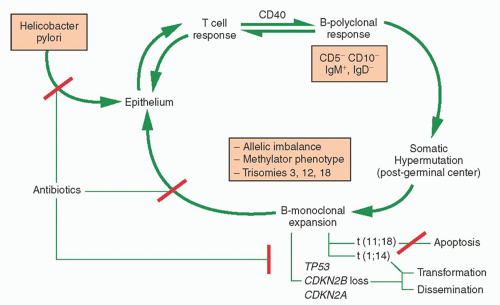

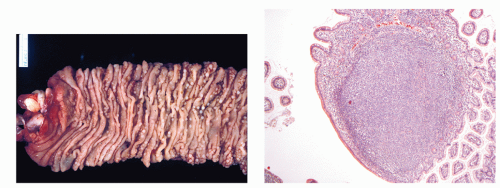

MALToma of the stomach serves as a model for lymphomagenesis secondary to antigenic stimulation (

Fig. 88.8).

102 Both B and T cells are recruited to the gastric mucosa following

H. pylori infection. Proliferation of B cells are dependent upon reactive T cells.

103 There is a continuous spectrum of pathologic lesions during the transition from gastritis to low grade MALToma to the less frequent large B cell.

102 PCR may be helpful in identifying a malignant B cell clone which may persist after histologic regression following antibiotic therapy.

104 Somatic hypermutation is characteristic of the B cell clone of MALToma and, along with the observation of plasmacytic differentiation, indicates a post germinal center origin. Translocation-positive gastric MALTomas lead to activation of the NF

κB pathway which causes overexpression

of BCL2, blocks apoptosis of B cells, and leads to antibiotic resistance, while translocation-negative cases involve inflammatory and immune responses, which maintain B and T cell interaction and respond to

H.

pylori eradication.

105 The oncoprotein of the

CAGA gene has been shown to be directly delivered into B cells by

H. pylori, and it likely contributes to lymphomagenesis.

106The most common genetic abnormality in gastric MALToma is the t(11;18)(q21;q21) which is present in one-quarter to one-third of cases, and up to one-half of

H. pylori negative cases.

107,

108 The genes involved at t(11;18) are an apoptosis inhibitor-2 gene (

API2) and a novel 18q gene,

MALT, and are more likely to result in disseminated disease but less likely to undergo histologic transformation than other genetic abnormalities.

109 The t(14:18) in MALToma involves

IGH/MALT2 and may coexist with trisomies 3, 12, or 18; occurs in 5% gastric MALTomas; and is more common in nongastrointestinal sites.

108 The t(1;14)(p22;q32) and t(1;2)(p22;q12) involve the

BCL10 gene

102,

110 and are present in 1% to 3% of gastric MALTomas.

102,

108,

110 BCL1 and

BCL2 gene rearrangements are usually not present in MALTomas, and

BCL-6 has rarely (1% to 2%) been reported.

102,

111 There is controversy whether the B cell clones remain dependent upon antigen stimulation or expand through autonomous (antigen-independent) growth. Loss of tumor suppressor genes and amplification of 3q27 have been associated with histologic progression and dissemination of MALTomas.

109,

112Other infections associated with specific MALTomas include

Borrelia burgdorferi with primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma,

Chlamydia psittaci with ocular adnexal MALTomas, and

Campylobacter jejuni with immunoproliferative small intestinal disease (also called alpha heavy chain disease or Mediterranean lymphoma).

46,

113 Their frequency varies according to endemic geography and have been found more commonly in Europe than in North America or Asia. The ability to diagnose the association depends upon either immunohistochemistry using a monoclonal antibody detecting the agent or, preferably, targeted polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that detects the DNA of the infectious agent. When the infections are present in these MALTomas, the lymphomas will regress in the majority of patients treated with antibiotics.

114,

115

Environmental Factors

Environmental associations implicated in the pathogenesis of NHL include not only infections, but also drug exposure and toxic chemical exposure. Immunosuppressive agents contribute to lymphomagenesis through interaction with EBV, particularly in organ transplants. Phenytoin and carbamazepine have been associated with both pseudolymphoma and malignant lymphoma, with the former condition presenting with fever, rash, and adenopathy that regress after drug withdrawal.

116 Methotrexate and the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha inhibitors (adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab) have been associated with an increased risk of lymphoma in some but not all studies in rheumatoid arthritis, which itself may have an increased risk (

see section on “Prelymphomatous Conditions”).

117 In a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies, there was a trend for an increased risk of B-NHL in patients receiving anti-TNF therapy, but it did not reach statistical significance.

118 Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma has been reported in patients with Crohn disease receiving anti-TNF therapy usually with other immunomodulators.

119 Although epidemiologic studies are flawed by methodologic weaknesses, other drugs possibly associated with NHL include analgesics, antibiotics, steroids, digitalis, estrogen, and tranquilizers.

44,

120,

121,

122 A Danish study found no increased risk of NHL in women using postmenopausal hormone replacement.

123Occupational exposures have been suggested as factors in the epidemic, but studies are often flawed because of small numbers and being retrospective. An increased risk of NHL has been reported among people employed in agriculture, forestry, fishing, construction, motor vehicles, telephone communication, and leather Industries.

124,

125 Specific jobs at risk include plant and poultry farmers, butchers, gardeners, painters and plasterers, car repair and gasoline station workers, carpenters, brick and stone masons, plumbers, welders and solderers, roofers, and teachers. The associations tend to increase with longer duration of employment, and studies have correlated specific jobs with histologic types.

125Chemicals that have been implicated in the epidemic include organochlorines and phenoxyacetic acids that are commonly found in pesticides and herbicides.

126,

127,

128,

129 A number of organochlorine compounds have been banned in the United States, including dichlorodiphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT, used from 1939 to 1972), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs, 1929 to 1977), and chlordane (1947 to 1988); however, studies have correlated the presence of these and similar chemicals in carpet dust and in adipose tissue with a higher risk of developing NHL. An excess risk for NHL has also been suggested for exposure to organic solvents, such as benzene, xylene, toluene and trichloroethylene, fertilizers, epoxy glues, and wood dust.

130 Variations in immune genes or DNA repair genes may affect an individual’s risk of developing NHL after exposure to solvents,

131,

132 which may also directly impair cell-mediated immunity.

Hair dyes, ultraviolet light (UV), and nutritional factors have been implicated in some epidemiologic studies and negated in others.

133,

134,

135,

136 Hair dye is more likely to be a factor in women than in men because of greater use in women. There has been an increased risk for NHL in women who used hair dyes before 1980, but not among women after 1980, probably related to removal of carcinogenic compounds.

136,

137Several studies noted an increase in NHL among patients with melanoma or squamous cell skin cancer and suggested a role for UV suppressing the immune system;

133 however, there was no correlation between NHL mortality and increased UV light exposure in the southern United States or in Scandinavia.

134,

138 Additionally, a reduced risk of NHL has been reported with higher sun exposure.

138,

139 A hypothesis is that reduced risk in midlatitudes arises from vitamin D production with UVB light, while an increased risk arises from immunosuppression by more UVA light in higher latitudes.

140 Other studies have found no protective effect of UV radiation and no association between vitamin D and NHL risk.

141,

142Nutritional factors, including milk, butter, liver, meat, coffee, and cola consumption, have been identified as possible risk factors.

143,

144,

145,

146,

147 A high-meat diet and a high intake of fat from animal sources have been associated with an increased risk of NHL; there was a decreased risk with increased ingestion of fruits.

135 Other studies have reported a lower risk for NHL with higher intakes of vegetables, lutein and zeaxanthin, and zinc.

148 Milk consumption has had conflicting reports.

135,

147 Obesity and lack of exercise have been suggested as contributing to the epidemic in some studies and refuted in others.

147,

149,

150Blood transfusion has been implicated as contributing to the increased incidence of NHL.

151,

152,

153 The use of blood products beginning in the 1950s has coincided with the epidemic. Transmission of infectious agents through blood transfusion could suppress the immune system, and make a patient susceptible to the development of lymphoma. Blood transfusion has been associated with all types of histologies, but a meta-analysis found a higher risk for CLL/SLL.

152,

153 While cohort studies have supported the connection between blood transfusion and lymphoma, case-control studies have not consistently confirmed the association.

151,

153,

154A number of other factors have been mentioned as possibly contributing to the epidemic, including ionizing radiation, electromagnetic fields, alcohol, tobacco, and chronic fatigue syndrome, but the data is weak to support an association of any of these factors

with an increased risk of NHL.

155,

156,

157,

158 The epidemiology of NHL continues under investigation and requires carefully designed studies with large cohorts and prolonged follow-up to determine the validity of an association between a factor and NHL. InterLymph, an international consortium of NHL studies, is providing large databases to assess the impact of environmental risk factors.

159