Neoplasms of the vulva and vagina

Summer B. Dewdney, MD  Jacob Rotmensch, MD

Jacob Rotmensch, MD

Overview

Vulvar and vaginal carcinomas are uncommon diseases that generally affect post-menopausal women, although 19% of vulvar carcinomas occur in women >50 years old. Risk factors for vulvar cancer include human papilloma virus and chronic inflammation. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia can often be managed with wide local excision, but several other modalities have been utilized. Most vulvar malignancies are squamous cell carcinomas that are managed by surgical excision and radiotherapy. Sentinel lymph node biopsy has been used to spare the morbidity observed after regional lymph node dissection. For more advanced lesions, chemo-radiotherapy with agents such as 5-FU, cisplatin, and mitomycin C is utilized. Other vulvar malignancies include Bartholin gland carcinomas, basal cell carcinomas, verrucous carcinomas, and melanomas. Carcinomas of the vagina are most frequently squamous cell, but clear cell adenocarcinomas have been seen in younger women. In the past, clear cell carcinomas were associated with prenatal exposure to diethyl-stibestrol. Vaginal melanomas can occur, as well as endodermal sinus tumors, rhrabdomysarcomas, and fibroepithelial vagina polyps.

Cancer of the vulva

Incidence and epidemiology

Vulvar cancer accounts for about 4% of cancers in the female reproductive organs and 0.6% of all cancers in women. It is the fourth most frequent gynecologic cancer.1 The American Cancer Society estimated that in 2014, about 4850 cancers of the vulva were diagnosed in the United States and about 1030 women die of this cancer.2

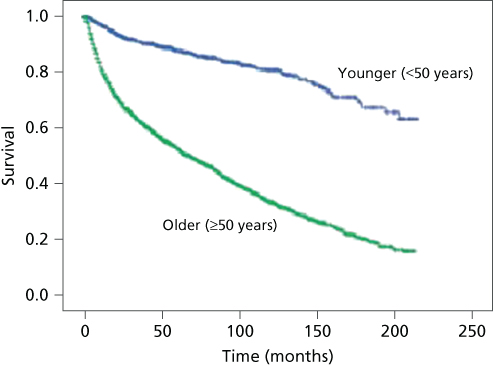

Risk factors include cigarette smoking, human papillomavirus (HPV), vulvar or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, chronic immunosuppression, chronic vulvar inflammatory diseases (e.g., lichen sclerosis and lichen planus), and northern European ancestry.3 Most vulvar carcinomas occur in older women, with more than 50% of the patients being 60–79 years of age. Kumar et al. found that younger patients with vulvar cancer are increasing with frequency, and through evaluation of the SEER database found that 19.3% of patients diagnosed with vulvar cancer are <50 years old. In addition, there is a striking survival difference between the younger and older women with squamous cell vulvar cancer (Figure 1).4

Figure 1 Comparison of survival of younger patients (<50 years; blue line) with that of older patients (≥50 years; green line) with squamous cell cancer of the vulva, 1988–2005. Log-rank p = 0.001. Source: Kumar 2009.4 Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.

This increased frequency in younger patients may be attributed to an increase in HPV, specifically HPV-related vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia that progresses to cancer.

Vulvar cancer is thought to develop through two types of pathways, the first related to HPV infections and the second related to a chronic inflammatory process.5 Several epidemiologic studies suggest a sexually transmitted origin for carcinoma of the vulva. Condyloma acuminatum associated with HPV has been noted in many patients with premalignant and malignant vulvar disease. It has been estimated that in the United States, over 1 million women each year develop perineal warts and that as many as 10% are infected with HPV.6 Currently, HPV types 6 and 11 are most frequently found in benign vulvar warts, and HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, and 45 are more frequently associated with intraepithelial neoplasia or invasive carcinoma.6–8 HPV can be found in approximately 50% of vulvar carcinomas; the tumors are often multifocal and associated with vulvar dysplasias. HPV-negative tumors are often found in older women.9, 10 These can be associated with chronic inflammatory disease as seen with vulvar dystrophies.

Although epidemiologic evidence strongly suggests a viral cause, other associations have been implied as well. Factors such as granulomatous diseases of the vulva, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity also have been associated with vulvar carcinoma, but perhaps this is because of the usually advanced age of patients. A case–control study by Mabuchi et al.11 found that domestic servants, or those working in laundry or cleaning plants, have an increased risk of vulvar carcinoma, thus suggesting an environmental component.

The association of carcinoma in situ (CIS) with invasive carcinoma of the vulva indicates a continuum from preinvasive to invasive carcinoma. Jones et al.12 evaluated 405 cases of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) 2–3, they found that 3.8% of patients that are treated will progress to cancer, and 10 patients who did not undergo treatment progressed in 3.9 years (mean). Progression, however, may differ between younger and older patients. Some authors suggest that the multifocal CIS of women in their thirties or forties is less likely to progress compared to older women.13–15

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasias

In 2004, The International Society for the Study of Vulvar Disease developed the current classification system for VIN (Table 1). Previous classification included VIN 1, 2, and 3 according to the degree of abnormality. Currently, only high-grade disease is defined as VIN and hence would take that nomenclature. It has been shown that VIN 1 is not a cancer precursor and therefore is not described as VIN. In 2004, they developed two categories to describe VIN: VIN, usual type (includes former VIN 2 and 3 of warty or basaloid and mixed types), and VIN, differentiated type (associated with lichen sclerosis).16 In addition, the College of American Pathologists and the ASCCP confirmed a two-tier system with the recent Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST) terminology project.17 American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) and the American Society for Colposcopic and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) issued a committee opinion on treatment of VIN cases given that there has been such an increase over the past 30 years, confirming agreement with International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISVDD) nomenclature of VIN differentiated type and usual type, and discussing treatment recommendations. Of note, many pathologists and practitioners still use the old classifications.

Table 1 Classifications of vulvar dysplasias

| Old classifications |

| Intraepithelial dysplasia |

| Mild dysplasia (VIN I) |

| Moderate dysplasia (VIN II) |

| Severe dysplasia (VIN III) |

| Current classifications (ISSVD 2004) |

| VIN-differentiated (associated with vulvar dermatologic conditions) |

| VIN-usual type (including warty, basaloid, and mixed VIN, associated with HPV) |

Abbreviations: VIN, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia; HPV, human papillomavirus.

VIN can present with a variety of symptoms. The most common is irritation or itching; however, 20% of patients are asymptomatic.18 Grossly, the lesions can be flat, raised (maculopapular), or verrucous. In color, they may be brown (hyperpigmented), red (erythroplastic), white, or discolored.

White lesions can appear to have a whitish, thickened keratin layer (leukoplakia) or a diffuse, white, brittle, paperlike appearance (lichen sclerosus) (Figure 2). Areas of squamous hyperplasia (hyperplastic dystrophy) and dysplasia can also have a white appearance. Unlike lichen sclerosus, however, the tissue often is thickened, and the process tends to be focal or multifocal rather than diffuse.15 It is important to biopsy lichen sclerosis as there may be an underlying vulvar carcinoma.19, 20

Figure 2 White, brittle paperlike appearance or lichen sclerosus of the vulva.

Microscopically, atypical changes in the vulvar epithelium consistent with preinvasive lesions usually are marked by loss of maturation of the squamous epithelium. There are increased mitotic activity and an increase in the nuclear cytoplasmic ratio.

There is suggestion that there are two distinct causes of vulvar dysplasia leading to vulvar cancer. The first type is seen in younger patients and is related to HPV infection and smoking. This type presents itself as a “warty” dysplasia. The more common type is in elderly patients and is unrelated to smoking or HPV. This group is more related to lichen sclerosis adjacent to the tumor. Approximately 20% of vulvar cancer has been reported to have vulvar dysplasia.

The best method of establishing a diagnosis is a high index of suspicion and early biopsy. Several methods also can be used to help assess these lesions. Cytology, colposcopy, acetic acid, and toluidine blue O can be used cautiously before biopsy. In general, however, cytologic evaluation of the vulva has not been helpful as a screening examination because the vulvar skin often is thickened and keratinized. Colposcopic examination of the vulva is difficult because unlike cervical lesions, the changes are difficult to recognize. Therefore, colposcopic examination is not used for routine vulvar examination; rather, it is primarily employed for patients who are being evaluated or followed for vulvar atypia or intraepithelial malignancies. The toluidine blue O test is nonspecific and stains nuclei in the superficial part of the epithelium. Colposcopy is performed after applying a 1% aqueous solution of toluidine blue O to the vulva for 1 min and decolorizing the tissue with 1% acetic acid. Areas that retain the stain are biopsied. A positive test, however, does not always indicate a premalignant condition because 20% of benign areas on the vulva stain positively.19

To obtain the entire thickness of the skin for a definitive diagnosis, a biopsy of the vulva usually is done with a Keyes dermal punch. Occasionally, a larger biopsy is needed, in which case a larger field can be locally anesthetized with lidocaine and a small scalpel or cervical biopsy punch used to obtain a specimen.21

Once the correct diagnosis has been established by biopsy, appropriate therapy can be undertaken. For lichen sclerosis, local measures, for example, wearing cotton underclothes and avoiding strong soaps and detergents, often are used to diminish irritation. Topical fluorinated corticosteroids applied twice daily for 1–2 weeks are helpful in controlling pruritus, but prolonged use of these steroid preparations can lead to vulvar atrophy or contracture. If long-term therapy is needed, a nonfluorinated compound such as 1% hydrocortisone is used. Some patients with lichen sclerosus have severe contracture in the area of the posterior fourchette. Treating these areas surgically with plastic repair of the fourchette has been suggested.22, 23

VIN can be treated by a variety of methods, and many authors have reported successful control of the disease by wide local excision.10, 22 Adequate margins must be obtained with wide excision; however, this often may be difficult because of the multifocal nature of the disease. Wallbillich et al.24 found that positive margins increased recurrence from 11% to 32%, and recurrence was associated with smoking and a large lesion size.

Other modalities also have been reported in the treatment of VIN. Carbon dioxide laser vaporization and photodynamic therapy25 of the vulva to a depth of 3 mm have been used, and current evidence indicates that laser therapy is as effective as surgical excision for the control of this disease. Before lasering the vulva, however, it is necessary to ascertain by histologic confirmation that invasive disease does not exist. Leuchter et al.26 treated 142 patients with CIS of the vulva. Of those treated by laser, 17% had a recurrence, a result that is similar to that in lesions treated by local excision.

Imiquimod has been used also for conservative medical treatment. A systematic review that included two randomized control trials found a complete response rate of 51%.27 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) cream has been used successfully to treat CIS of the vulva, and application of this has been reported to be successful in 75% of cases. With continuous application, however, this treatment causes edema and pain. Most recently, a multicenter, randomized, phase 2 trial between cidofovir and imiquimod for treatment of VIN3 showed a response rate of approximately 46% for both groups treated.28

Paget disease

Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial disorder of the vulvar skin that is seen in postmenopausal women.29–31 Unlike VIN, the intraepithelial neoplastic cells are glandular rather than squamous. The lesion primarily occurs in Caucasians of an average age of 65 years. Grossly, it appears as a reddish, eczematoid lesion. Microscopically, this type of lesion is characterized by large pale cells that often occur in nests and infiltrate the epithelium. Once the diagnosis is made, it is important to rule out the presence of an underlying cancer. Invasive vulvar Paget disease occurs in approximately 10% of Paget disease.20 If the anal area is involved, one needs to consider an anal carcinoma. A review by Lee et al.30 reported a total of 75 cases of Paget disease of the vulva: 16 (22%) of the patients had underlying invasive carcinoma of the adnexal structures and 7 (9%) had adnexal CIS.

Paget disease of the vulva often spreads in an occult manner, with margins extending beyond the normal appearance of the lesion.31 If there is no evidence of an underlying malignant neoplasm, a wide local excision or total vulvectomy usually is performed.32 If a wide local excision is performed, a slightly deeper excision is needed to remove the epidermis down to the level of the underlying fat to ensure removal of adnexal skin structures. Because this lesion extends subepithelially, a frozen section in the operating room may assist in ensuring complete removal.

Bergen et al. evaluated 14 patients with Paget disease of the vulva that was treated by vulvectomy, skinning vulvectomy with a graft, or hemivulvectomy.32 With a median follow-up of 50 months, all patients were free of disease; however, three patients had locally recurrent disease. Other modalities (topical 5-FU cream, laser) have not been used for treatment of this disease. Because both local and distant recurrence is a major risk, close follow-up is required.

Invasive vulvar carcinomas

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) adopted a new surgical staging system in 2009 (Table 2). This surgical staging has been modified once prior, in 1995, after it became a surgically staged cancer in 1989. The most recent staging system addresses lack of predictive value seen in the previous stages with regard to the size of the lesion, and number and size of lymph node metastasis.32 Specifically, in the new system, there was an addition of three pathologic groupings within stage III (A, B, and C): this identifies the number of positive node, the size of each node, and extracapsular spread. In addition, many centers use the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) classification.

Table 2 TNM classification and staging of vulvar carcinoma

| TNM classification | ||

| T | Primary tumor | |

| Tis | Preinvasive carcinoma (CIS) | |

| T1 | Tumor confined to the vulva and/or perineum; 2 cm or less in diameter | |

| T2 | Tumor confined to the vulva and/or perineum; more than 2 cm in diameter | |

| T3 | Tumor of any size with adjacent spread to the urethra, vagina, or anus | |

| T4 | Tumor of any size infiltrating the bladder mucosa, the rectal mucosa, or both, including the upper part of the urethral mucosa, or fixed to the anus | |

| N | Regional lymph nodes | |

| N0 | No nodes palpable | |

| N1 | Unilateral regional lymph node metastases | |

| N2 | Bilateral regional lymph node metastases | |

| M | Distant metastases | |

| M0 | No clinical metastases | |

| M1 | Distant metastases (including pelvic lymph node metastases) | |

| FIGO staging (2009) | ||

| IA | T1aN0M0 | Tumor confined to the vulva and/or perineum: 2 cm or less in greatest dimension, ≤1 mm stromal invasion, no nodal metastasis |

| IB | T1aN0M0 | Tumor confined to the vulva and/or perineum: 2 cm or greater in greatest dimension, >1 mm stromal invasion, no nodal metastasis |

| II | T2 | Tumor of any size with extension to adjacent perineal structures (1/3 lower urethra, 1/3 lower vagina, anus) with negative nodes |

| IIIA | T1 or T2, N1a or N1b, M0 | Tumor of any size with or without extension to adjacent perineal structures (1/3 lower urethra, 1/3 lower vagina, and anus) and positive inguinofemoral lymph node, (1) 1–2 lymph node metastasis (<5 mm) or (2) 1 lymph node metastasis ≥5 mm |

| IIIB | T1 or T2, N2a or N2b, M0 | Tumor of any size with or without extension to adjacent perineal structures (1/3 lower urethra, 1/3 lower vagina, and anus) and positive inguinofemoral lymph node, (1) 3 or more lymph node metastaisis (<5 mm) or (2) 2 or more lymph node metastasis ≥5 mm |

| IIIC | T1 or T2, N2c, M0 | Positive node with extracapsular spread |

| IVA | Tumor invades any of the following: upper urethra, bladder mucosa, rectal mucosa, pelvic bone, and/or bilateral regional node metastasis | |

| IVB | Any distant metastasis including pelvic lymph nodes | |

Abbreviations: FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; TNM, tumor, node, and metastasis.

Source: Adapted from Barakat 2013.

Vulvar cancer can spread by direct extension, lymphatic embolization, or hematogenous dissemination. Metastasis to the femoral nodes without inguinal node involvement has been reported but is uncommon. The direct lymphatic pathways from the clitoris to the pelvic nodes have been described but are not of clinical significance. The overall incidence of lymph node metastasis is approximately 30%. Pelvic node metastasis is uncommon with an overall frequency of 9%. Approximately 20% of patients with positive groin nodes have positive pelvic nodes.33, 34

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinomas comprise approximately 90% of primary vulvar malignancies. Grossly, these carcinomas usually appear as ulcerated or polyploid masses on the vulva. Biopsy reveals the characteristic histologic appearance: the tumor appears in nests and cords of squamous cells infiltrating the stroma, often with islands of keratin. On physical examination, there is usually an ulcerated lesion or wart-like lesion. Recently, there has been an increased incidence of warty carcinoma accounting for 20% of all cases.

Different clinical results have been reported with this definition. Spread to regional lymph nodes has varied from 0% to 10% in tumors with less than a 5 mm depth of invasion.35–40 For example, Hoffman et al.38 reported no nodal metastases in 43 patients whose tumor invaded <2 mm. Lesions that were at risk of spreading to inguinal nodes included tumors with confluent tongues rather than those with individual tongues merely extending into the stroma. Depth of invasion of the stroma to ≤1 mm is associated with a risk of lymph nodes metastasis of <1%, hence no need for patient with <1 mm stromal invasion to undergo an inguinal lymph node dissection. Tumors with a depth of invasion of 1.1–3.0 mm are associated with lymph node metastasis of 6–12%, and this rate increases to 15–20% with a depth of invasion of 3.1–5 mm.41

The risk of nodal involvement may be decreased when CIS is present in the lesion. Rowley et al.39 noted that only 1 of 35 cases with adjacent CIS had nodal metastases. By contrast, 5 of 27 had positive lymph nodes when superficial stage I lesions penetrating 2.1–5.0 mm did not have adjacent CIS.

Sentinel inguinal lymph node biopsy

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is being used in vulvar cancer. In patients with a clinically negative groin examination, an SLNB is an alternative to inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. SLNB results in less morbidity without compromising detection for lymph node metastases. The Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG 173) compares SLNB to inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy in 452 women with squamous cell vulvar cancer, for tumors with a depth >1 mm, and size between 2 and 6 cm.42 The sensitivity of the SLNB is 92%, and the negative predictive value is 96% in this study. Another multicenter observational study GROnigen INternational Study on Sentinel nodes in Vulvar cancer (GROINSS-V) analyzed 623 groins from 403 patients, confirming a decrease in short- and long-term morbidities.

Patients undergoing an SLNB report less treatment-related morbidity compared to inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy without compromising the overall quality of life.43The results of the observational study GROINSS-V II, evaluating and performing a full inguinofemoral lymph node dissection in the setting of a positive SLNB and observation only of a negative SLNB, are still pending.

The above-mentioned studies are all based on surgeons with “vast experience” performing SLNBs. It is still recommended that in the setting of lack of expertise with SLNB, an inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy is done, which is common in the setting of vulvar cancer, which is overall a rare cancer.

Treatment

Clinical stage IA

Tumors showing a depth of the stroma 1 mm or less have minimal risk for lymphatic dissemination. They do not require an inguinofemoral lymph node dissection because the risk of lymph node metastases in this setting is very low risk. These lesions are usually treated with a wide radical excision. These patients have a high cure rate; however, surveillance is needed to rule out recurrence.

Clinical stage I/II

The recommendation for a clinical stage I or II vulvar cancer is a wide radical excision with unilateral or bilateral SLNB versus an inguinal femoral lymphadenectomy (depending on size, location, and institution) for both staging and therapeutic purposes. Margins need to include at least a 2 cm margin lateral of normal tissue, with the deep margin to the deep perineal fascia. The laterality of the lesion determines the need for bilateral versus unilateral inguinofemoral lymph node dissection (or SLNB). A subanalysis of GOG 173 shows that a bilateral lymph node dissection is required except when the tumor is located more than 2 cm or greater from the midline. For both stages I and II, surgical resection usually leads to excellent long-term survival and local control.

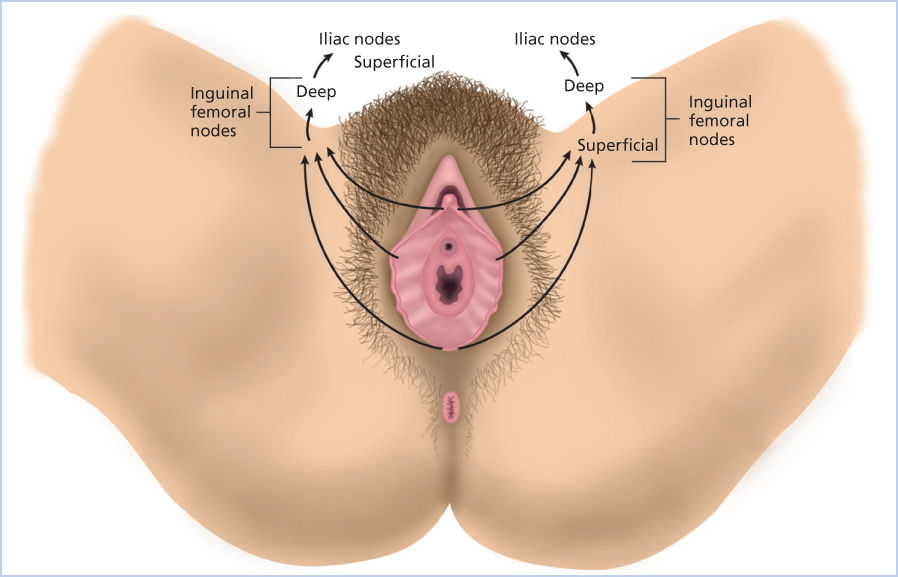

The pattern of spread for this carcinoma relates to the intricate lymphatic drainage of the vulva (Figure 3). Tumors located in the middle of either labium initially drain to the ipsilateral inguinal femoral nodes, whereas midline perineal tumors can spread to either the left or right side. Using technetium-99 m colloid, Iversen and Aas showed that when radioactivity was injected to one side of the vulva, 98% of it localized in the ipsilateral nodes and <2% in the contralateral nodes.34 Tumors along the midline in the clitoral or urethral areas may spread to either groin. From the inguinal-femoral nodes, lymphatic spread continues to the deep pelvic iliac and obturator nodes. Although there has been concern in the past that tumors in the clitoral–urethral area could spread directly to the deep pelvic nodes, current evidence indicates that this is rare.

Figure 3 Lymphatic drainage of the vulva.

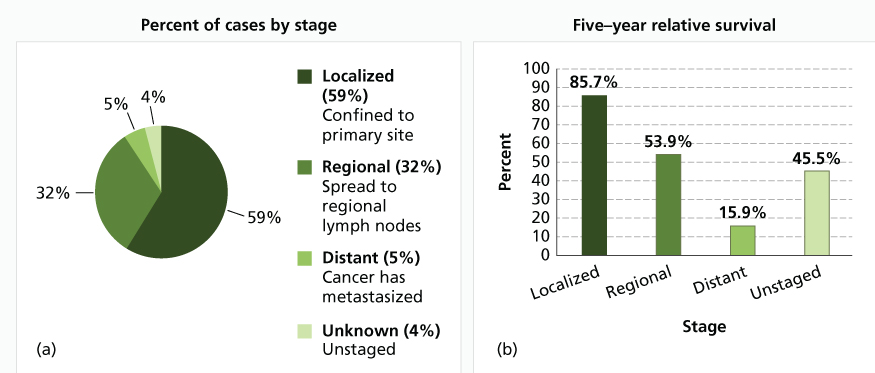

Stages I, II, and III invasive carcinoma

The prognosis of a patient with vulvar carcinoma relates to the stage of disease (Figure 4). The presence of carcinoma in the regional lymph nodes correlates with the size and thickness of the primary lesion, the degree of tumor differentiation, and the involvement of vascular spaces by the tumor as seen in Table 3, which comes from a classic study by Sedlis et al.44 In 272 women with invasive vulvar carcinoma reported by the GOG, regional nodes were involved in 8.9% of stage I, 25.3% of stage II, and 31.1% of stage III lesions.45, 46 With larger lesions, 4 mm or greater in thickness, 31% of nodes were positive. Hacker et al.47 reported an actuarial 5-year survival rate of 96% in those with negative nodes survival decreased to 94% with one positive node, 80% with two positive nodes, and 12% with three or more nodes involved by tumor.

Figure 4 (a) Percent of cases and (b) 5-year relative survival by stage at diagnosis: vulvar cancer. Source: National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) 2011. Stat Fact Sheets: Vulvar Cancer (reproduced from http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/vulva.html, accessed 12 Feb 2015).

Table 3 Prognostic factors of stage, grade, and tumor thickness associated with positive regional nodes

| Stage | Positive nodes (%) | Grade | Positive nodes (%) | Tumor thickness (mm) | Positive nodes (%) |

| I | 8.9 | 1 | 0 | <1 | 3.1 |

| II | 25.3 | 2 | 8.0 | 2 | 8.9 |

| III | 31.1 | 3 | 24.6 | 3 | 18.6 |

| IV | 62.5 | 4 | 47.7 | >4 | 31.0 |

Source: Sedlis 1987.44 Reproduced with permission of AJOG.

Not only is the number of nodes important but there also appears to be a correlation with the size of the metastases. Hoffman et al.48 noted that 14 of 15 patients with inguinal lymph node metastases measuring <36 mm survived free of disease for 5 years compared with 12 of 29 patients whose tumor metastases measured >100 mm. No additional treatment may be advised if only one lymph node in the groin in microscopically positive; however, this is controversial. Patients with stage 1 lesions did not have positive nodes, yet in patients with stage 4 lesions, 47.7% of nodes were positive. Vascular space involvement is prognostic with 72% vascular invasion showing regional node metastasis compared to 34% of those without vascular invasion. Nodal involvement also correlates with the location of the primary lesion.49 Lesions on the labia are associated with 7.4% positive nodes, whereas clitoral lesions have a higher incidence of positive nodes (27.4%).50 Boyce et al.51 reported that six tumors under 1 cm in diameter had no metastases to regional nodes but that the fraction of tumors with positive nodes rose to 55% for 29 cases with lesions over 4 cm.

Therapy for stages I and II and early stage III vulvar carcinoma is accomplished with radical vulvectomy and either bilateral inguinal femoral node dissection52 or SLNB. In the past, en bloc of radical vulvectomy and bilateral dissection of the groin and pelvic nodes were standard treatments (specimen seen in Figure 5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree